How preservationists and Jackie O got the supreme court to save Grand Central Terminal in 1978

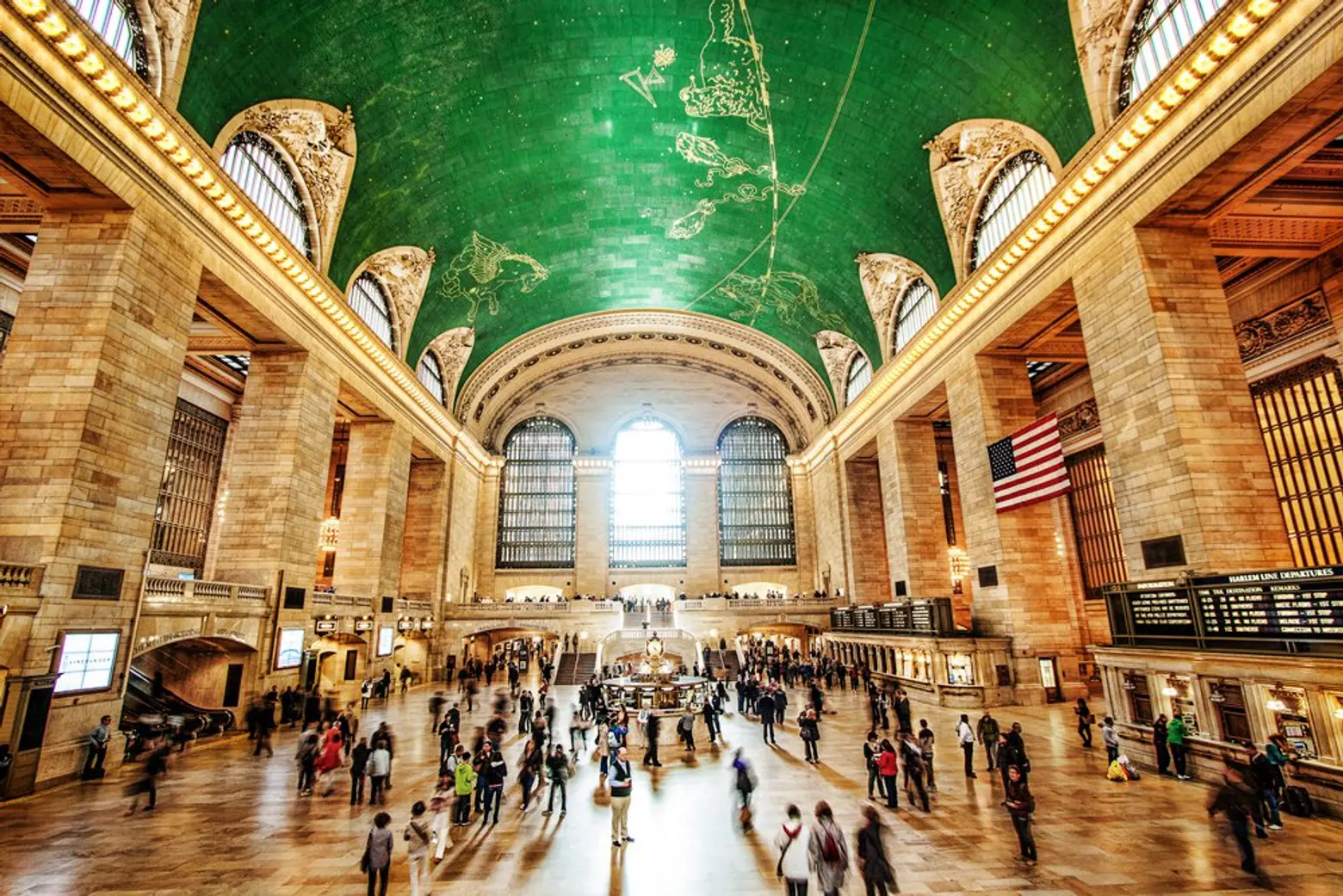

Grand Central Terminal Lobby via Wikipedia

On June 26th, 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a momentous decision that wouldn’t just save a cherished New York landmark, it would establish the NYC Landmarks Law for years to come. This drawn-out court battle was the result of a plan, introduced in the late 1960s, to demolish a significant portion of Grand Central Terminal and erect a 50-story office tower.

Though the proposal may seem unthinkable now, it wasn’t at the time. Pennsylvania Station had been demolished a few years earlier, with the owners citing rising costs to upkeep the building as train ridership sharply declined. The NYC Landmarks Law was only established in 1965, the idea of preservation still novel in a city practicing wide-scale urban renewal. Finally, Grand Central wasn’t in good shape itself, falling apart, covered in grime, and home to one of the highest homeless populations in New York City. But a dedicated group of preservationists–aided by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis–took the fight to the highest levels of the court. Keep reading to find out how, as well as learn about the celebrations planned by the MTA surrounding the anniversary.

The original Pennsylvania Station via Wiki Commons

The original Pennsylvania Station via Wiki Commons

The 1960s was not a good decade for the great train stations built in cities across the county in the early 20th century. Travelers were not taking long-distance trains, opting to drive or fly instead. Lavish train hubs were difficult to maintain as money drained out of them. And so, developers looked for opportunities to redevelop.

In 1963, McKim Mead and White’s Pennsylvania Station was one of the first train hubs to be lost to the wrecking ball. It was replaced by Madison Square Garden on top and current-day Penn Station below –hardly worthy replacements for one of the grandest train stations in New York. The devastating architectural loss prompted then-Mayor Robert F. Wagner to create the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965. Just two years later, the commission designated Grand Central a landmark.

Protecting Grand Central would not be so easy. Stuart Saunders, who spearheaded the demolition of Pennsylvania Station, had merged the former rivals, the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroad, to form Penn Central. He became the CEO of the nation’s biggest real estate corporation at the time — and Grand Central Terminal was among Penn Central’s holdings. Unfazed from his experience demolishing Penn Station, Saunders looked to make this second historic train hub as profitable as possible.

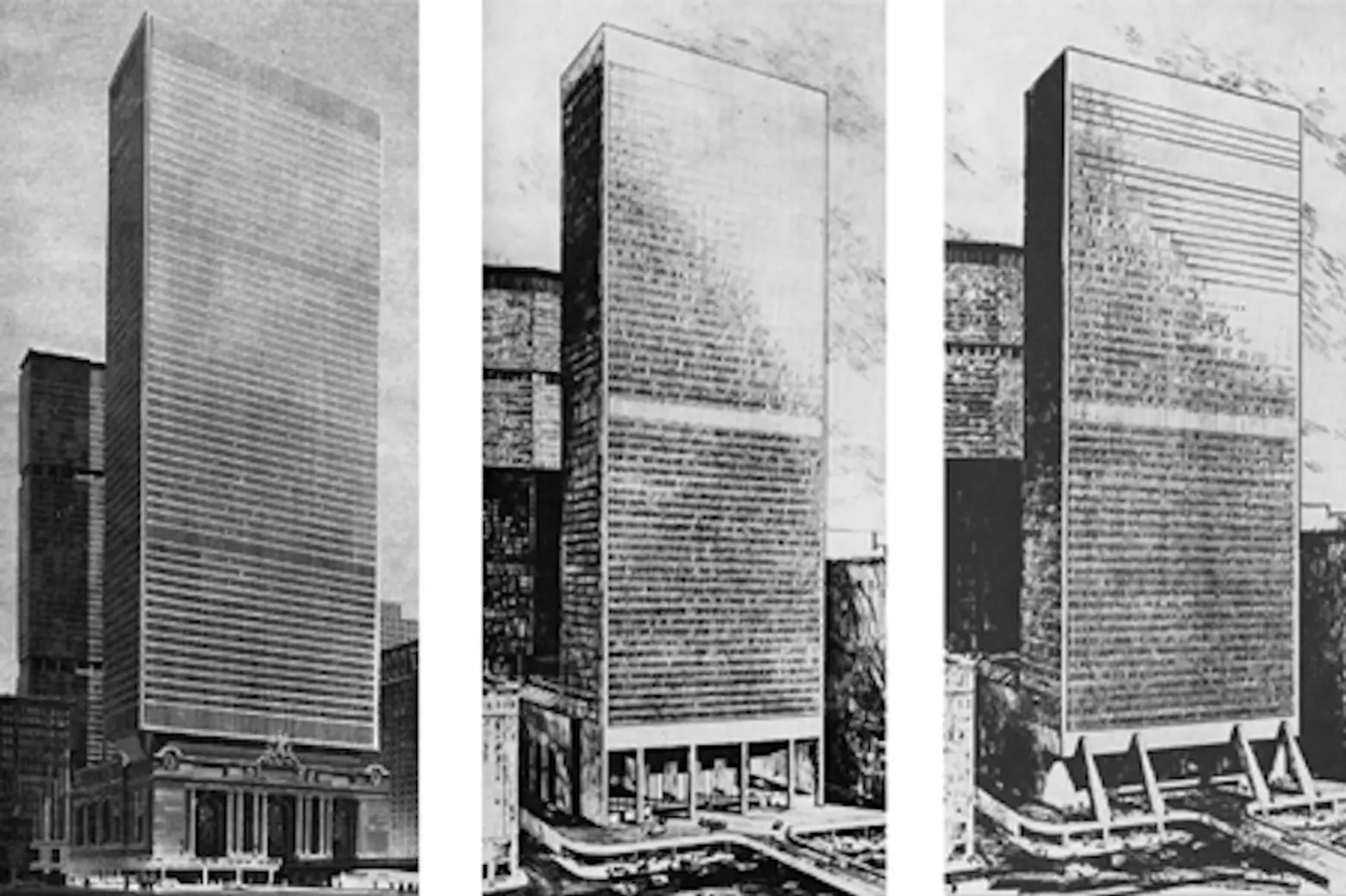

Marcel Breuer’s proposals to add a tower atop Grand Central

Marcel Breuer’s proposals to add a tower atop Grand Central

Not long after GCT became a landmark, Saunders began soliciting bids for an office tower to be built atop the terminal. Marcel Breuer’s design proposals, pictured above, were widely circulated as possible outcomes. To build the tower, however, would require significant demolition of the terminal’s Beaux Arts structure.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission denied any proposal to demolish the terminal and plop a tower on top. Saunders wouldn’t take no for an answer, suing the city with the argument that the ruling was unconstitutional in that it went “beyond the scope of any permissible regulation and constitute[d] a taking of plaintiff’s private property for public use without just compensation.”

In 1975, a New York State Supreme Court judge agreed with Penn Central. They ruled that the terminal elicited “no reaction here other than that of a long neglected faded beauty.”

That’s when local preservations sprung into action — they didn’t want the same fate for Grand Central as Pennsylvania Station. The Municipal Art Society created a “Committee to Save Grand Central Terminal.” One surprising member: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who graciously lent her voice to make a case for preserving the terminal.

On January 30th, 1975, the group announced its mission at the Oyster Bar. Onassis told reporters, “We’ve all heard that it’s too late… even in the 11th hour, it’s not too late.” Mayor Wagner added that “the battle against the thoughtless waste of our manmade environment is farther from being won than many of us had thought.” He knew that if Penn Central succeeded with their case, New York’s entire landmarks law would be in danger: “What is at issue here is the very concept of landmark preservation,” he told the crowd.

Legal back-and-forth ensued: the city appealed the New York State Supreme Court judge’s ruling and won, then Penn Central appealed to the highest court in the state and lost. Finally, the case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1979.

The Committee To Save Grand Central Terminal on the Landmark Express, courtesy Wikipedia

The Committee To Save Grand Central Terminal on the Landmark Express, courtesy Wikipedia

To build support for the cause, Onassis and other prominent preservationists organized the “Landmark Express,” a one-day Amtrak trip from Penn Station to Washington, D.C. on the day the Supreme Court began hearing arguments. The train picked up passengers in Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore. McDonald’s hamburgers and fries were offered, not to mention entertainment by fire-eaters, mimes, clowns and musicians. Passengers even came up with their own song: “Let’s make a grand stand to save Grand Central, the greatest landmark of all. It’s a great part of New York City like the lights of old Broadway, Let’s make a grand, grand stand for Grand Central, for the good old U.S.A.”

Two months after the momentous trip, on June 26th, 1978, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of New York City’s Landmark Law. Penn Central, which had been bankrupt for eight years, was defeated. Grand Central Terminal was officially saved. The landmarks law, too, withstood the test of the courts and would go on to protect thousands more historic buildings across New York.

Ownership of Grand Central would eventually transfer to the MTA, who still owns and operates the terminal today. In 1998, the MTA kicked off an ambitious restoration of the building after suffering from years of neglect. This October marks the 20th anniversary of a renovation that restored the landmark and transformed the terminal into a popular retail and dining destination.

If you feel like celebrating, the MTA is offering a few opportunities. There will be an exhibition this September by the Municipal Art Society of New York, in partnership with the New York Transit Museum, inside the terminal’s Vanderbilt Hall. It’ll tell the story of the Committee to Save Grand Central’s historic advocacy campaign alongside before-and-after photographs of the 1998 restoration.

A series of tasting events will take place all summer long, starting with Taste of the Terminal June 26 through June 28 where the public can enjoy free food and product samples, a 40th-anniversary photo installation, and live music in Vanderbilt Hall. Additional tasting events will take place in Grand Central Market in July and the Dining Concourse in September.

There will also be a lineup of musical acts featuring 1990s tunes (to honor the 1990s terminal restoration) in a lunchtime music series taking place weekly on Tuesdays in July and August.

For all the details, go here.

RELATED: