The Urban Lens: Ash Thayer’s poignant photographs of ’90s Lower East Side squatters

6sqft’s series The Urban Lens invites photographers to share work exploring a theme or a place within New York City. In this installment, Ash Thayer shares intimate punk portraits of Lower East Side squatters from the 1990s. The photos are part of her collection “KILL CITY,” which was recently compiled into a book and published under the same name.

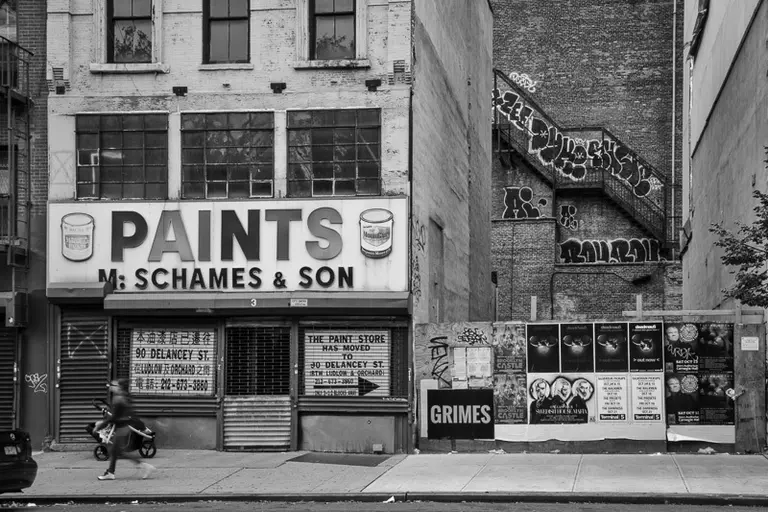

These days it’s difficult to think of the Lower East Side as much more than a destination for bar hopping, rapidly rising rents, and general raucousness, but not that long ago the neighborhood was a place pulsating with community, character, and openness to all walks: including squatters. One such squatter who found solace in this once distinct downtown enclave was photographer Ash Thayer who came to the city in the early ’90s to enroll at the School of Visual Arts, but after a series of misfortunes (e.g. a shady landlord who stole her security deposit) found herself homeless.

Thayer, however, had always had an affinity with the counterculture community and it didn’t take long for the kids of NYC’s punk scene to lend her a hand. In 1992, she joined the See Skwat, one of several squats she’d ultimately spend eight years living in and documenting. Ahead, Thayer shares some of her emotional photography from her time at See Skwat, and she speaks to 6sqft about her experience living in what she describes as an “important piece of the unknown history of New York.”

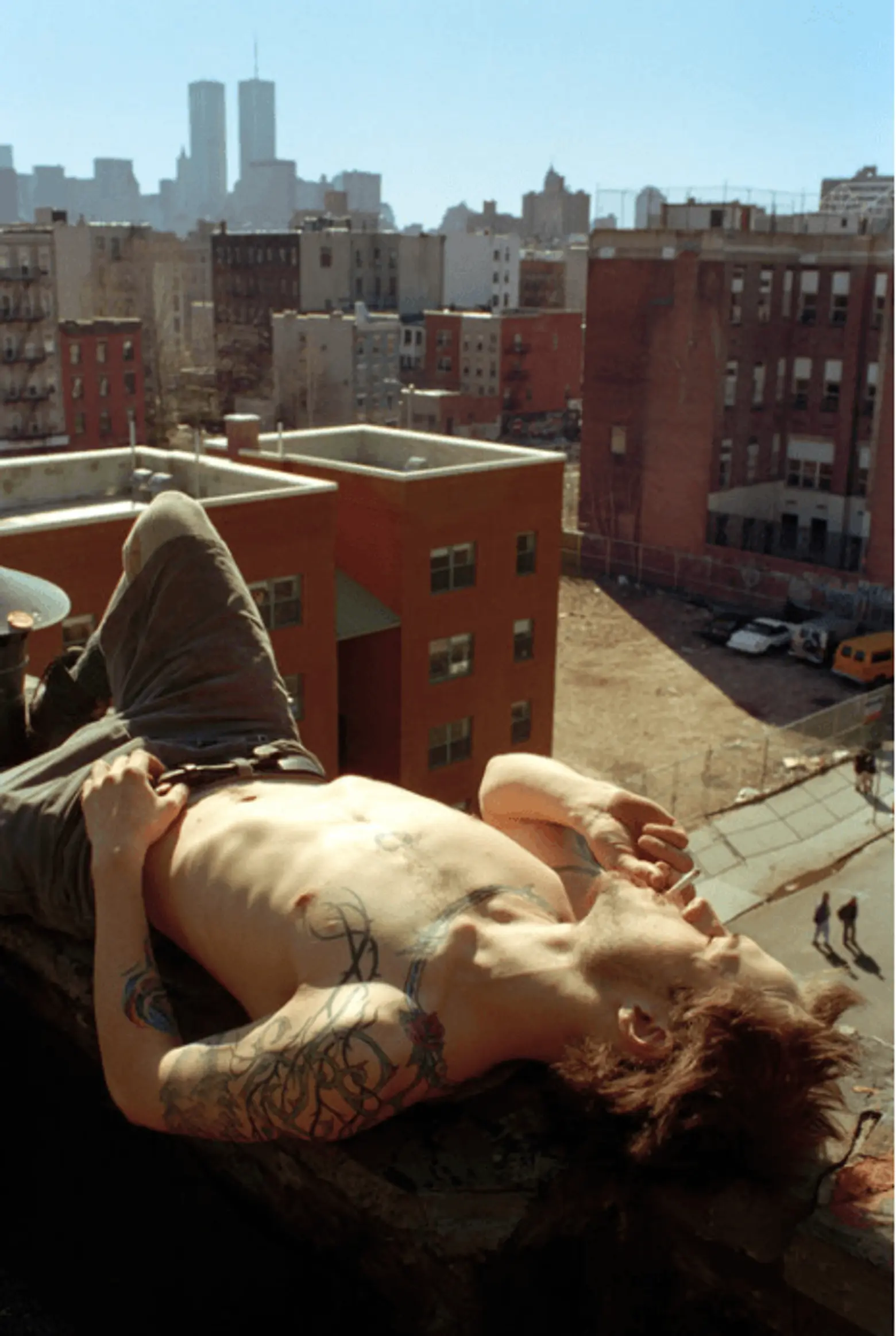

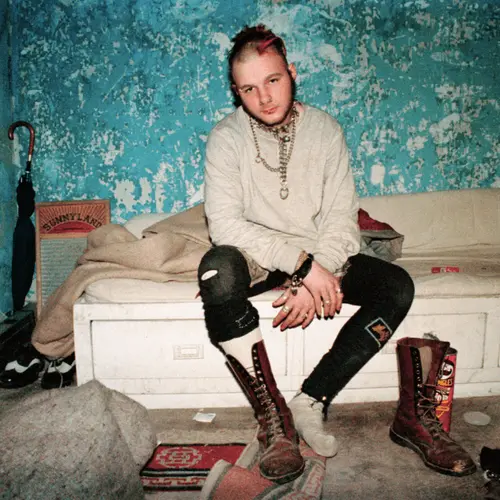

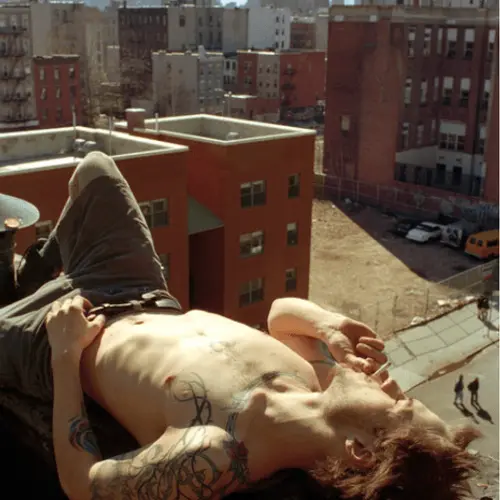

Mattie on Serenity Roof, 1997

Mattie on Serenity Roof, 1997

What prompted you to start taking photos of what was going on around you? Were you drawn to specific situations or were you just documenting everything?

I had been photographing my friends within the punk rock/anarchist/DIY community starting in my senior year of high school. I was very much in the moment, making images of who and what I was passionate about. When I began art school at SVA, I noticed most of the students pursuing fashion and other types of commercial work, which I had a really hard time getting interested in, so I just stuck with my friends and counterculture community, which was endlessly more fascinating and beautiful to me than the commercial world of art whose purpose was in creating desire while inciting personal insecurities in order to generate consumption of products and goods to achieve personal fulfillment. In short, I did not want to use photography as a tool to manipulate audiences. That much I was sure of at the time.

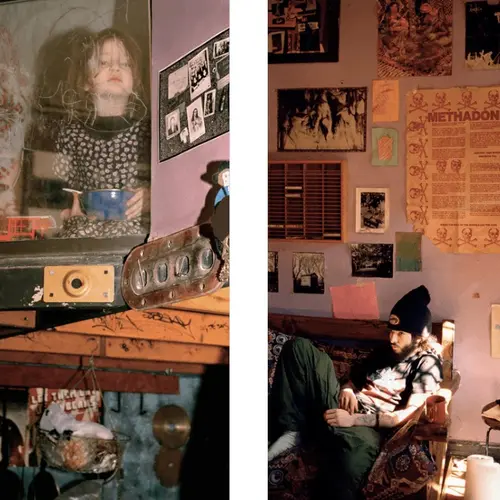

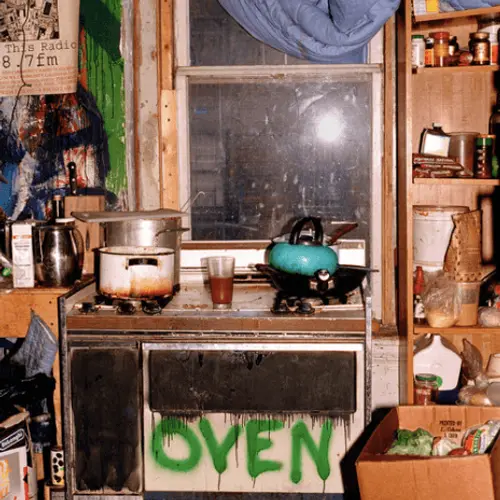

Child’s Room, Serenity House, 1997 (top left); Sqwert, Serenity House, 1997 (top right); Bed and broom, 5th St. Squat, 1995 (bottom)

Child’s Room, Serenity House, 1997 (top left); Sqwert, Serenity House, 1997 (top right); Bed and broom, 5th St. Squat, 1995 (bottom)

What were some of the toughest situations you or your friends found yourselves in during the time?

The winters were close to unbearable if you did not have a small room with insulated walls or enough electricity to heat it. The cold was miserable and it separated the real squatters from the “summer campers” who just came stayed in NY for the months with nice weather. Living without water was rough because we had to haul it up in containers after getting it from fire hydrants.

Entering and exiting the building could be stressful if you knew your building was being watched by the city. There were examples of police and city inspectors attempting to come inside the building when residents were coming or going, which could lead to an immediate eviction if they got in. They could make a claim that there was a building code violation and that it put the residents in imminent danger. If the city was pushing for an eviction, you were pretty much screwed if anyone got in. Hence the secrecy, high level of commitment and trust amongst residents, and a limited number of door keys.

When the 13th Street evictions took place, there was a huge standoff between squatters and local residents and Mayor Guiliani,’s massive police presence. It was one of the most publicized evictions of five buildings and was a heartbreaking loss for our community.

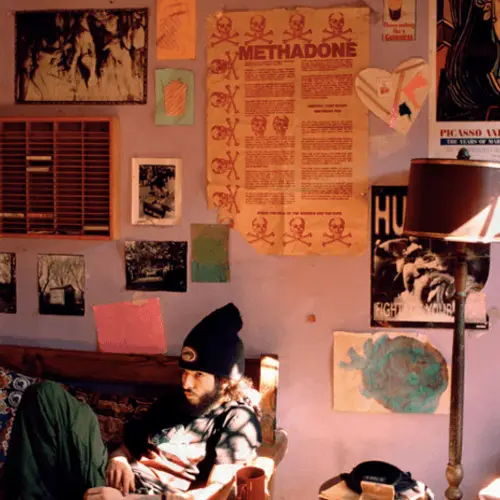

Caroline looking out of her window, Serenity House, 1996 (top); Joey looking at a map, See Sqwat, 1997 (bottom)

Caroline looking out of her window, Serenity House, 1996 (top); Joey looking at a map, See Sqwat, 1997 (bottom)

Was there a lot of conflict with the police or neighbors?

The Lower East Side has always been a melting pot of different lower income ethnicities and communities, that is until the late 80s and 90s. In the late 70s and 80s, from what I have been told, there was initial tension between some of the residents who had been there for decades and squatters, due to fears around gentrification. When young middle-class white people start moving into a neighborhood, it’s a guarantee that rents will rise. However, the squatters were all lower income and earned the trust of neighbors by cleaning up empty lots and chasing out many of the drug dealers, criminals, and junkies that made the neighborhood unsafe. I am speaking in very general terms here. Drug use was often a problem within the squatting community, even though most buildings had rules against hard drugs.

There was constant conflict between squatters and police, particularly as a result of Mayor Guiliani’s war on squatters and homeless people in general. Instead of constructively dealing with the issue of homelessness and lack of affordable housing, his solution was to evict squatters and arrest people sleeping on the streets. He made evicting squatters from their long-time homes part of his campaign for election. Since real estate investors had been chomping at the bit to gentrify the LES and break up its long-standing communities for their own profit, this motivated them to help elect Guliani.

The police became his personal militia, paid for by New York taxpayers. He spent millions of tax dollars on evicting poor families.

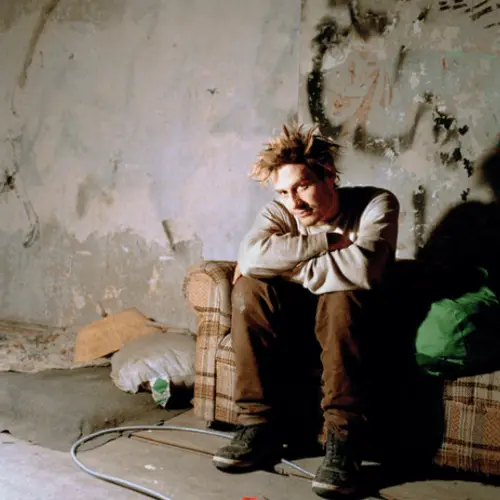

Famous, Pregnant and building windows, 7th St. Squat, 1994

Famous, Pregnant and building windows, 7th St. Squat, 1994

You squatted for eight years, when did you decide to move on from the squat?

I did not squat for eight years straight. I bounced in and out of apartments whenever I could afford it. Because of school, and time constraints, it was difficult to commit to a building and take on an entire apartment or studio and build it from the beams up. So, I would stay with other squatters in their apartments (or what was to become an apartment) and help them, as well as contributing labor on the building and shared spaces, like stairwells, electric, masonry, roof work, etc.

It was a full-time job occupying and creating homes in these buildings and it left little time for other jobs. We lived in the construction sites. Once an apartment and the building had the basics (which would often take years), then there was time for personal pursuits. The clock was always ticking to bring the building up to city codes as quickly as possible to avoid eviction.

The project organically came to a close when I decide to move to Los Angeles in 1998. It was such a culture shock that I didn’t stay there long. I lived in my hometown, Memphis for a year or two, working on a project before getting accepted to graduate school at both Yale and Columbia. These opportunities were too good to pass up, or so I thought at the time, so I returned to NYC to attend Columbia. I lived in Crown Heights, then Bushwick.

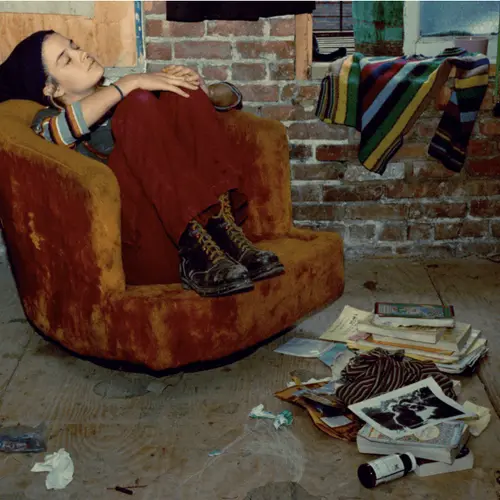

Carrie taking a break in window, 5th St. Squat, 1995

Carrie taking a break in window, 5th St. Squat, 1995

Why did you decide to put all of these images in a book?

It was an opportunity that came about as a result of Colin Moyniham, a writer at The New York Times, publishing an article and group of images from this series. Another previous squatter, Stacy Wakefield, contacted me and helped me create a book proposal, which resulted in powerHouse offering to publish it. I had rather lost hope that anyone would be interested in exhibiting or publishing this project. I knew that it was an important piece of the unknown history of New York, much like the incredible stories documented in Luc Sant’s book, Low Life. I received a lot of discouragement from professors and no gallery had been interested in exhibiting it, with very few exceptions. It has taken time for people’s perspectives to change regarding the ongoing housing crisis within our capitalistic structure and it took the market crash of 2008 to force Americans to see it as a real concern affecting our citizens. Owning a home is out of the question for most Americans today.

Are you still in contact with any of the folks you documented?

Yes, all of the time. I have maintained close relationships with many people. When the book was released we had a huge reunion party. I still stay with friends at See Skwat when I travel to NYC.

View from Serenity Roof overlooking 9th St. and Avenue C, 1998

View from Serenity Roof overlooking 9th St. and Avenue C, 1998

How does it feel when you go back to the LES now? To see how much NYC has changed in what’s been a relatively small window of time?

Well, it’s fairly shocking and tragic. It’s so sad to see small, family-owned businesses replaced with chain stores and banks. So much of the local character and uniqueness has been destroyed by lack of preservation, community planning and the city’s ruthless profit mongering. The Lower East Side feels like one big college dorm frat party, with a shrinking population of locals. New people moving in are literally renting what we would consider a large closet for several thousand dollars a month. It’s gross.

Any other projects we should keep an eye out for from you?

Oh, yes!

I have two projects I am working on that are very exciting to me! The first is called “Shotgun Baptism.” It is a photography and film based project addressing the shared experiences of women, minorities, and folks in the queer, trans, and non-binary gendered communities within the current patriarchal political structure in America.

The second is titled “Viking Women: The Crying Bones.” Seeking to challenge and problematize traditional androcentric readings of Viking women and their way of life, this project provides modern day visual tableaus that collude with historian Anna Bech Lund’s thesis, “Women and Weapons in the Viking Age.” It includes photographs and a large installation piece.

Website: www.ashthayer.net

Instagram: @at137

***

Are you a photographer who’d like to see your work featured on The Urban Lens? Get in touch with us at [email protected].

MORE FROM THE URBAN LENS:

- Langdon Clay’s 1970s photographs of automobiles also reveal a New York City in decay

- Travel back to the gritty Meatpacking District of the ’80s and ’90s

- Enter the vibrant world of New York City’s Sherpa community

All photographs courtesy of Ash Thayer

Explore NYC Virtually

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Wonderful photos, great story. Worth remembering that the LES was also squatted in the 60s and 70s. That was a different era of course and many of those squatters were able to legalize their housing with the city turning the buildings into either rent stabilized or even limited equity coop apartments.