‘The Alamo’ turns 50: A history of the Astor Place cube

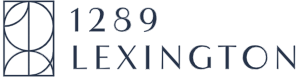

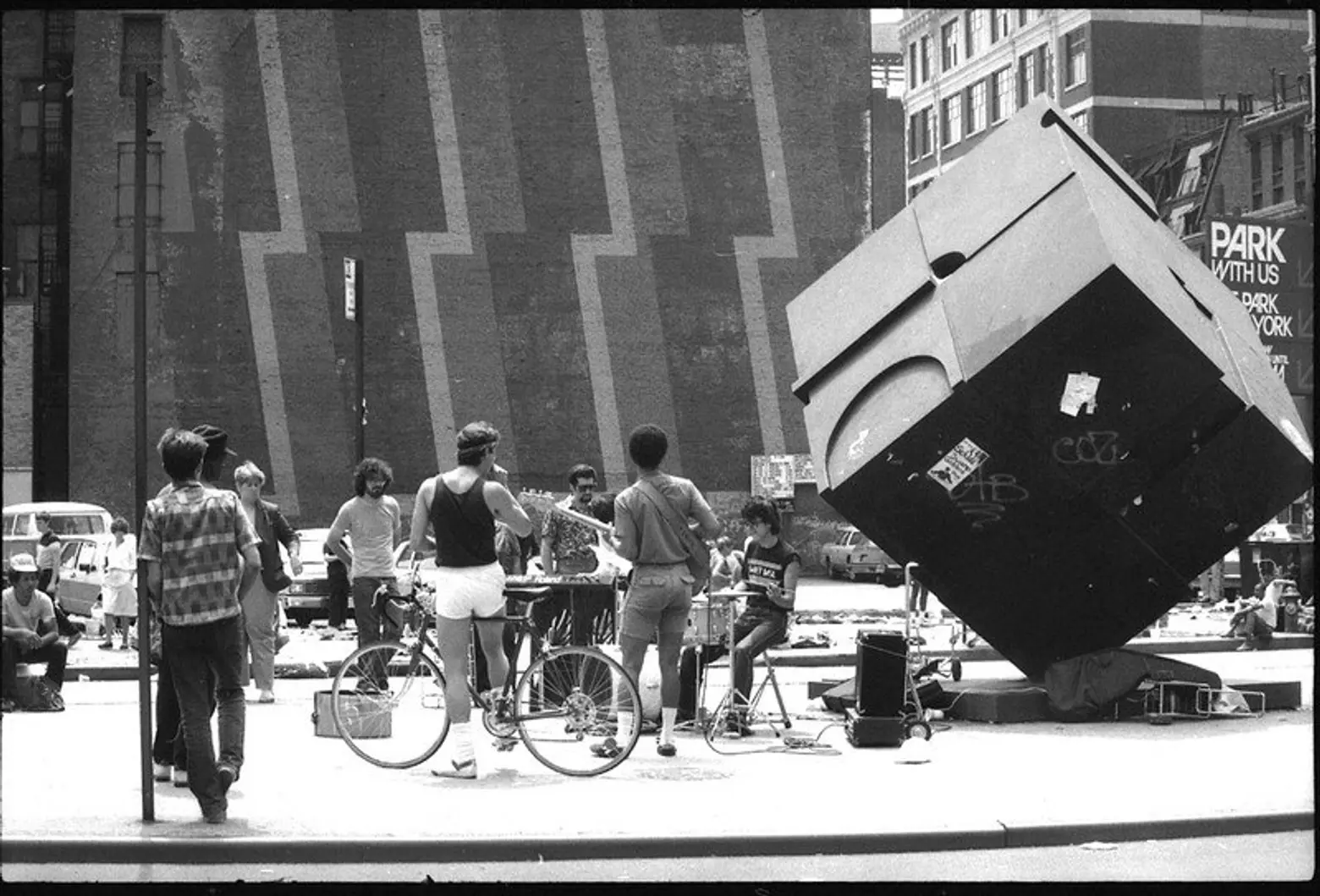

1980s photo of the Alamo surrounded by mural, vendors, & musicians. © Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Image Archive.

On November 1, 1967, an enigmatic 20-foot-tall cube first appeared on a lonely traffic island where Astor Place and 8th Street meet. Though several months before the release of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the one-ton Cor-Ten steel sculpture shared many qualities with the sci-fi classic’s inscrutable “black monolith,” at once both opaque and impenetrable and yet strangely compelling, drawing passersby to touch or interact with it to unlock its mysteries.

Fifty years later, Tony Rosenthal’s “Alamo” sculpture remains a beloved fixture in downtown New York. Like 2001’s monolith, it has witnessed a great deal of change, and yet continues to draw together the myriad people and communities which intersect at this location.

1980s photo of the Alamo surrounded by a flea market. © Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Image Archive.

1980s photo of the Alamo surrounded by a flea market. © Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Image Archive.

The Alamo’s longevity and lasting appeal belie its origins. One of 25 artworks installed by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs as part of its Sculpture and the Environment program, these and other artworks were only intended to be temporary. But the cryptic cube, named “The Alamo” by Rosenthal’s wife, who thought it was reminiscent of the famous mission where Texas independence fighters made their last stand, was a surprise hit. In the long tradition of temporary structures which won over their audience and became permanent, such as Washington Square Arch, the Eiffel Tower, and later, the London Eye, the Alamo soon became a permanent fixture downtown – the only one of the original artworks granted that stay of execution.

“Endover” via Adam Fagen/Flickr

“Endover” via Adam Fagen/Flickr

Its origins are not the only surprising thing about the Alamo. In spite of its apparent uniqueness, it’s not Tony Rosenthal’s only cube. In fact, versions of the sculpture can be found on the University of Michigan’s Ann Arbor campus (where it is called “Endover’), in the Pyramid Hill Sculpture Park in Hamilton, Ohio, and in private collections in Miami and Southampton. But Astor Place’s cube was the first and best known; it also bears the distinction of being the first permanent contemporary outdoor sculpture installed in New York City.

The Astor Place Tower, or “Sculpture for Living” via Wiki Commons. The Alamo is near its right-side base.

The Astor Place Tower, or “Sculpture for Living” via Wiki Commons. The Alamo is near its right-side base.

51 Astor Place, via Dan Deluca/Flickr

51 Astor Place, via Dan Deluca/Flickr

The Cube’s placement is no doubt an important part of its success, and certainly its significance. The sculpture stands at the crossroads of three great New York City neighborhoods – Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho. It also stands at the confluence of at least six different streets, in an unusually open valley amidst the canyons of New York City. Of course, the intersection was considerably more open 50 years ago, when the sculpture was first installed, than it is today; in 2005 Charles Gwathemy’s curving green Sculpture for Living tower just south of the cube replaced a parking lot where flea markets were often staged in the 1970s and ’80s. And in 2013, the black glass office tower at 51 Astor Place, sometimes referred to as “The Death Star” for its resemblance to the Star Wars vessel, replaced a considerably shorter six-story brick Cooper Union building.

But the intersection the Cube marks was even more open 500 years ago when this spot was not the confluence of three neighborhoods but three nations, known as “Kintecoying.” Literally meaning “crossroads of three nations,” it was where the three Native American groups which inhabited this part of New York in the 16th Century — the Canarsie, the Sapohannikan, and the Manhattan — converged. Though they lived in close proximity, each group spoke a different language. But here their major trails intersected, and a central meeting point was established. Leaders from each group would discuss issues, trade, and play games, including bagettaway, which we now call lacrosse. Astor Place, in fact, was built upon one of these original Native American trails.

Photo courtesy of the Village Alliance

Photo courtesy of the Village Alliance

In Native American tradition, this central meeting place would have been marked by a large oak or elm tree. Today, Tony Rosenthal’s considerably more abstracted piece plays a similar role, marking the spot where different communities still converge, and where people still talk, trade, or play games.

The game most associated with the Alamo is undoubtedly “spin the cube.” Those who are unfamiliar may not realize that the one-ton sculpture can actually spin on its pedestal. But it’s not easy and requires several sets of hands and strong backs, thus providing one of the many ways in which the sculpture brings people together.

The cube while yarn-bombed, via Dan DeLuca/Flickr

The cube while yarn-bombed, via Dan DeLuca/Flickr

The Alamo lends itself to some other kinds of games as well. In 2005 a group of pranksters going by the name All Too Flat transformed the sculpture into a giant Rubik’s Cube. And in 2011 guerilla street artist Olek “yarn bombed” the artwork, turning it into a giant crocheted cube.

Some thought a different kind of tomfoolery was underfoot when the Cube was removed for over a year from 2015 to 2016. In fact, the Cube was undergoing a good cleaning and some restoration work, done while Astor Place and Cooper Square underwent a redesign that included pedestrianizing the block of Astor Place abutting the sculpture. As a result of those changes the cube no longer stands encircled in traffic. Instead, it’s now locked in a stand-off with its neighbor to the south, the Sculpture for Living, which in spite of its name seems infinitely less alive than Tony Rosenthal’s half-century old public artwork.

“Steel Park” via Google Street View

“Steel Park” via Google Street View

If you’re craving more Tony Rosenthal sculpture, you needn’t travel farther than Lower Manhattan or the Upper East Side, as The Alamo is one of four public outdoor sculptures in the borough by the artist. His “5 in 1,” a series of red interlocking metal circular forms, sits on the public plaza between the NYC Municipal Building and Police Headquarters; “rondo,” a shiny 11- foot-tall welded bronze disc, can be found in front of the New York Public Library at 127 East 58th Street; and “Steel Park,” a 60-foot-long, 14-foot-high interactive sculpture, sits on a plaza in front of 401 East 80th Street at First Avenue. You can interact with all of them, but don’t try spinning any other than the cube.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED: