From natural history museum to municipal weather bureau: The many lives of Central Park’s Arsenal

The Arsenal c. 1914, via Library of Congress

New York City boasts more than 1,700 parks, playgrounds, and recreational facilities covering upwards of 14 percent of the land across all five boroughs. This sprawling network of greenery falls under the jurisdiction of the NYC Parks Department. Once the storied provenance of Robert Moses, the Department functions today under the less-Machiavellian machinations of Mitchell Silver. Though no longer the fiefdom it once was, Parks still operates out of a medieval fortress known as the Arsenal, a commanding bulwark stationed in Central Park at 5th Avenue and 64th Street.

The Arsenal also houses the Arsenal Gallery, the City Parks Foundation, the Historic House Trust, and the New York Wildlife Conservation Society. This wide array of agencies reflects the varied legacy of building itself. Since construction began on the Arsenal 1847 (completed 1851), it has served a stunning array of purposes, from police station to menagerie to weather bureau. The Arsenal has had time to live so many lives: it is one of just two buildings in Central Park that predate the park itself, which was established in 1857.

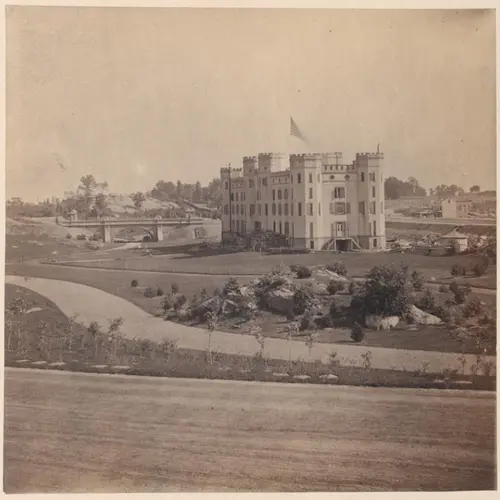

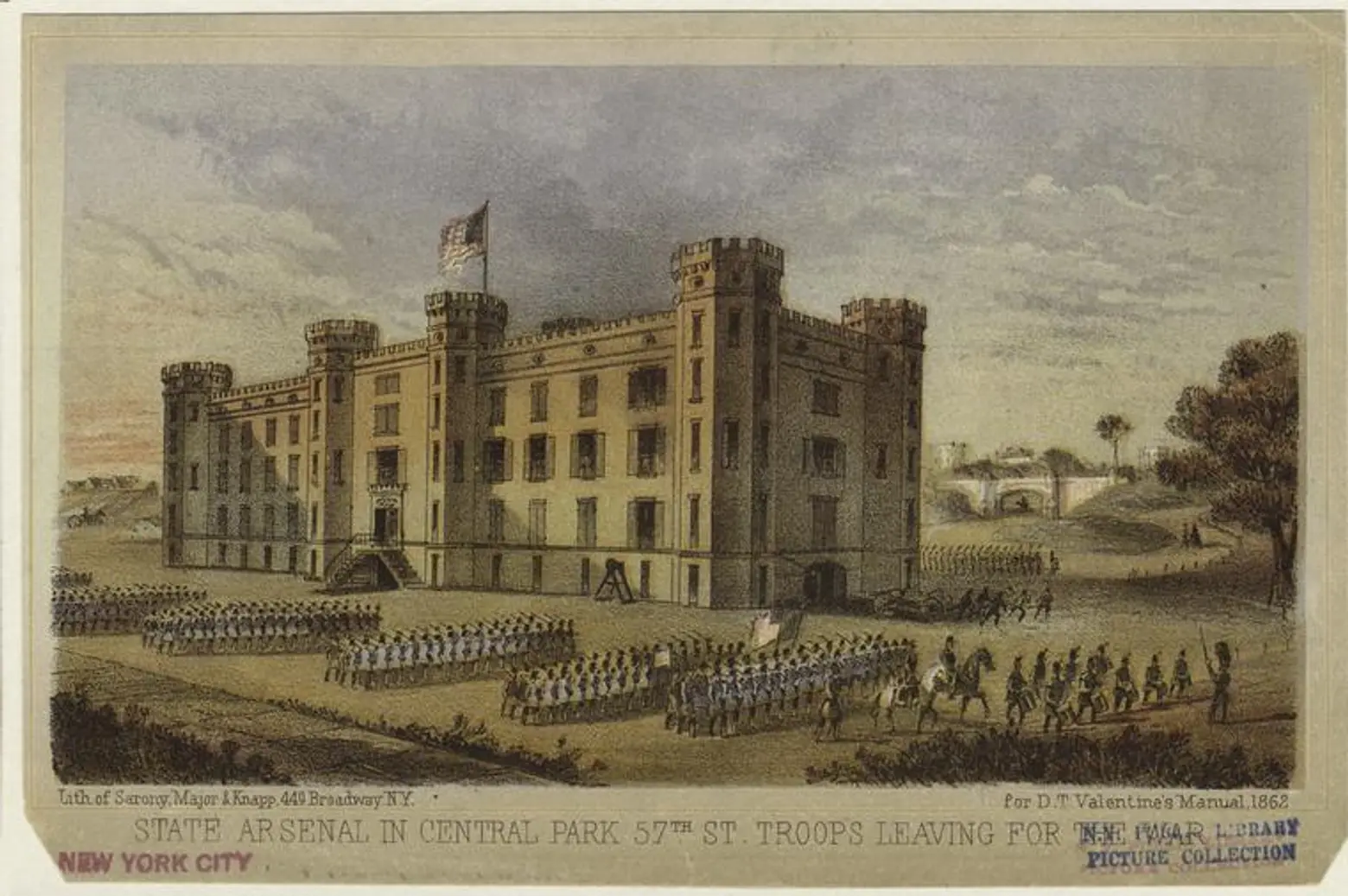

The Arsenal c. 1862, via NYPL

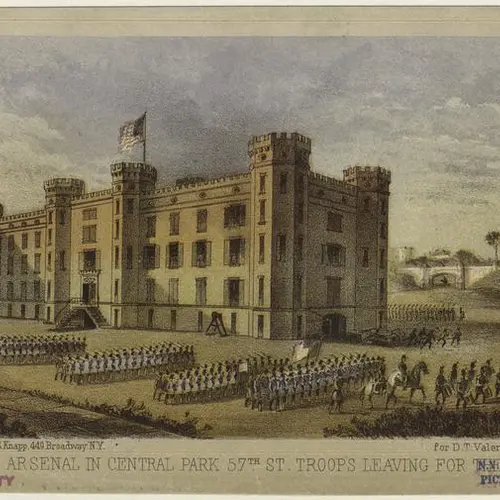

If the name “Arsenal” has you thinking of military maneuvers, you’re right on target. The Arsenal was originally built as an armory, “to house and protect the arms of the state.” That purpose inspired the building’s medieval design, which the Landmarks Preservation Commission describes as the “early English manorial fortress” style. This 5th Avenue fortress was built to replace the armory built in 1808 at Franklin and Center Streets and was funded by Millard Fillmore, who was then New York State Comptroller, a job he held before becoming President in 1850.

The Arsenal’s tenure as a storehouse for munitions was short-lived. When the City purchased the land and the building from New York State in 1857, for $275,000, all arms and munitions were removed, and the Arsenal served as headquarters for both Central Park’s administrative offices and Manhattan’s 11th police precinct.

The Arsenal seen from “Fifth Avenue Road” c. 1862, via NYPL

Two years later, New York’s Finest were joined in the building by some of New York’s furriest: a menagerie began to take shape in and around the Arsenal in 1859. The animals arrived as gifts or loans from men of renown including the circus impresario P. T. Barnum, the financier August Belmont, and the Union General William Tecumseh Sherman. The animals were housed in the basement of the building or in outdoor cages. Because it was dangerous to keep animals in the basement (and the smell wafting through the building proved less than delightful) the indoor cages were removed in 1871.

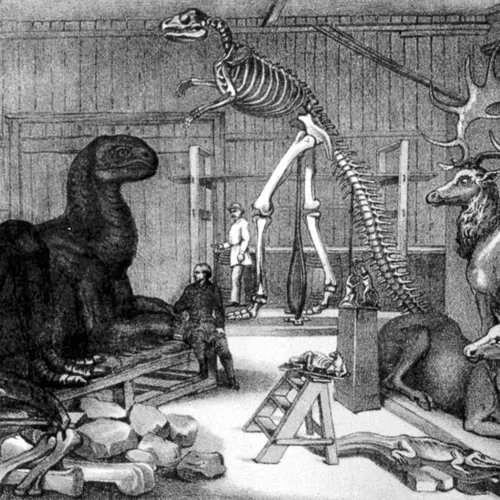

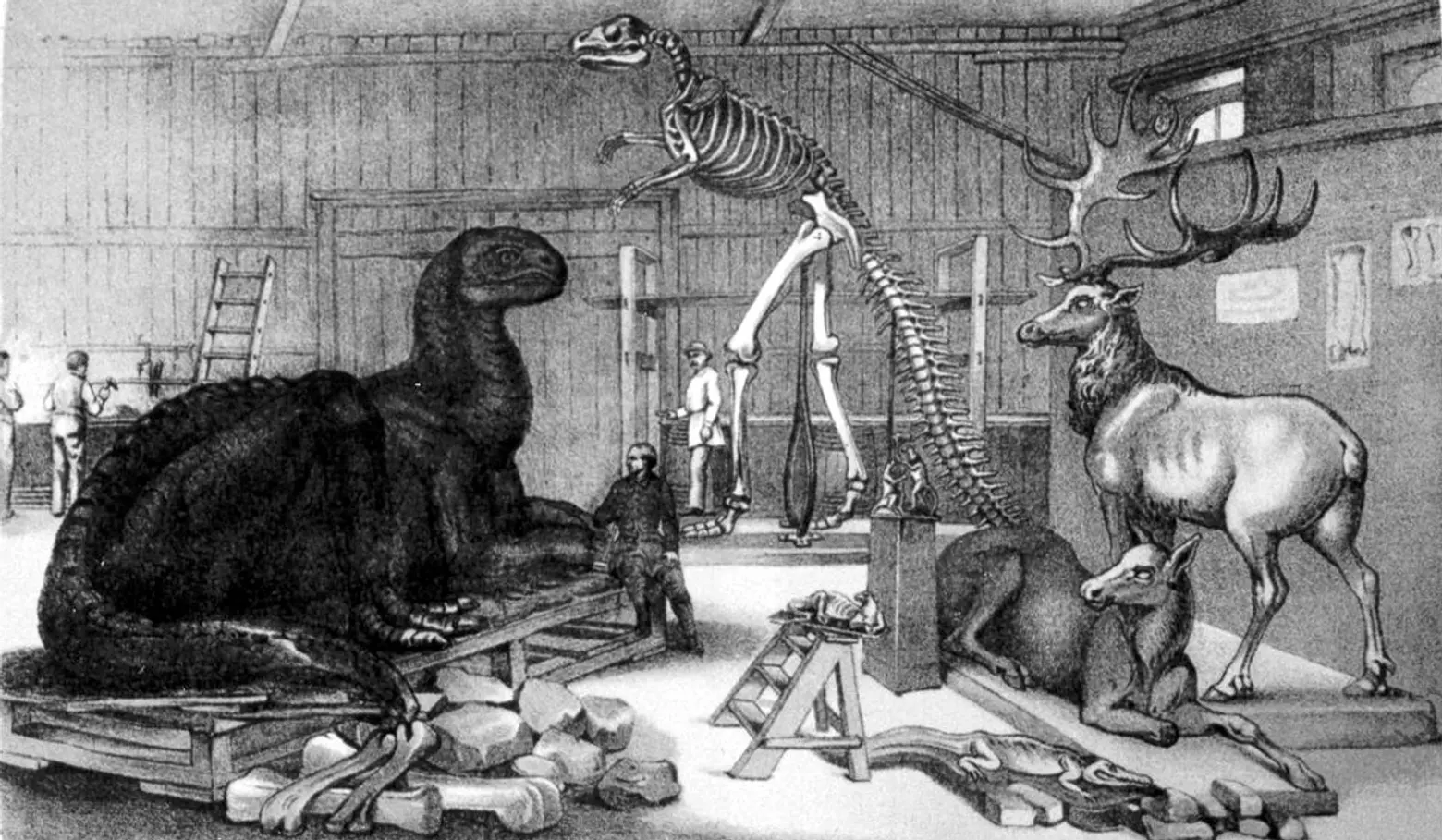

Paleontology studio within the Arsenal c. 1868, via Wiki Commons

Paleontology studio within the Arsenal c. 1868, via Wiki Commons

But, that didn’t mean that the Arsenal was without animals. By 1869, the building had begun switching gears from menagerie to museum. Before the American Museum of Natural History (designed by Central Park architect Calvert Vaux) opened on Central Park West in 1877, the museum made its first home at the Arsenal. For eight years, the Natural History Museum’s exhibits were installed on the Arsenal’s second and third floors, while the British paleontologist B. Waterhouse Hawkins was bent over dinosaur bones – reconstructing the skeletal remains – in a special studio at the Arsenal. But you wouldn’t just find exhibits on the building’s upper floors. At the same time, an art gallery graced the first-floor space.

From 1869 to 1918, the Municipal Weather Bureau stationed its instruments atop the Arsenal.

Despite this frenzy of activity, many parks advocates saw the Arsenal building as distinctly less beautiful than the glorious park it was in. As early as 1859, George Templeton Strong called the building “hideous” and hoped that it would “soon be destroyed by accidental fire.”

By 1870, the building experienced renovation rather than a conflagration. That year, architect Jacob Wrey Mould remodeled the building’s interior. Despite the revamp, the building had begun to languish in the early years of the 20th century, and the Manhattan Parks Department, then its own distinct agency, relocated to the newly opened Municipal Building in 1914, where it would stay for the next 10 years.

After decamping from the Arsenal, the Parks Department considered demolishing the building in 1916 and relocating the 11th precinct and the weather bureau to other locales within Central Park, such as Belvedere Castle.

It seems that in the case of Castle v. Fortress, the fortress triumphed, since the city undertook a $75,000 full-scale renovation of the Arsenal in 1924, to make the building once again suitable as Parks HQ. The restoration uncovered even more aspects of the building’s history: digging revealed both an underground spring and a secret subterranean passageway, which the Parks Department suggests may have been used for covert movement of arms when the building housed munitions.

Ten years later, the building was renovated again, this time under Robert Moses, who headquartered his unified citywide Parks Department in the Arsenal. Since Moses, together with Mayor La Guardia, succeeded in securing a stunning one-seventh of WPA funds for New York City during the first two years of the New Deal, the Commissioner made sure some of those funds were used to beautify the Arsenal. In 1935 and 1936, the Arsenal’s lobby was bedecked in beautiful WPA murals depicting the city’s finest parks and recreation facilities.

The Arsenal today, via Wiki Commons

The Arsenal today, via Wiki Commons

In 1967, the stalwart, long-surviving Arsenal was designated a New York City Landmark. Since the early 1980s, the building has revived one of its earliest roles as an exhibition space. For more than 30 years, the central chamber of the Arsenal’s third floor has been used as a gallery space for exhibits dedicated to “the natural environment, urban issues and parks history.” Currently on view you’ll find “Power to the People,” an exhibit of art and photography exploring the history of public protest in NYC Parks.

RELATED:

- INTERVIEW: Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver is making NYC parks accessible for everyone

- Stopped in its tracks: The fight against the subway through Central Park

- Billy goats and beer: When Central Park held goat beauty pageants

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.