Stopped in its tracks: The fight against the subway through Central Park

Photo by Phil Roeder / Flickr

In 2018, Mayor Bill de Blasio closed all of Central Park’s scenic drives to cars, finishing a process he began in 2015 when he banned vehicles north of 72nd Street. But not all mayors have been so keen on keeping Central Park transit free. In fact, in 1920, Mayor John Hylan had plans to run a subway through Central Park. Hylan, the 96th Mayor of New York City, in office from 1918 to 1925, had a one-track mind, and that track was for trains. He had spent his life in locomotives, first laying rails for the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad (later the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, or BRT), then rising through the ranks to become a conductor. In that capacity, he was involved in a near-accident that almost flattened his supervisor, whereupon he was fired from the BRT. Nevertheless, Hylan made transit his political mission, implementing the city’s first Independent subway line and proposing that it run from 59th Street up through Central Park to 110th Street.

John F. Hylan, 1917, via WikiCommons

John F. Hylan, 1917, via WikiCommons

Hylan maintained that the near knock-out had been his supervisor’s fault, and nursed a serious grudge against privately owned mass-transit conglomerates all the way to City Hall! In fact, he halted the proposed subway between Brooklyn and Staten Island simply because it was a BRT job. Construction for the tunnel that would have connected Staten Island and Brooklyn was already underway when he killed it, so the city was left with two holes at either terminus. Fittingly, they got the alliterative nickname, Hylan’s Holes!

Despite this act of subway suicide, he made transit the centerpiece of his mayoralty. He won the mayor’s seat by campaigning against the IRT’s proposed fare hike, which would raise fairs above 5 cents, which New Yorkers had been paying since the system opened in 1904. Fares stayed put, and Hylan got the city’s top job.

As Mayor, he became even more zealous about the subway. At the time, the city entrusted its growing subway network to two private companies, the IRT and the BRT. But Hylan, still sore about his unceremonious booting from the BRT, railed against what he called “the interests” of organized private power, which he likened to a giant octopus [that] sprawls its slimy legs over our cities states and nation,” and dreamed of a municipal subway system that would wrest power from the large companies.

And so was born the city’s Independent Lines. Hylan called christened his Independent Lines the ISS (Independent Subway System). The city itself would come to know them as the IND.

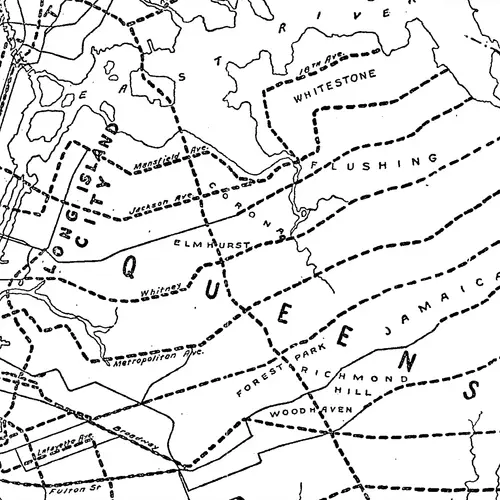

The centerpiece of the Independent Subway was the 8th Avenue Line (today’s A/C/E service). It was the first Independent line to open, in 1932, a full seven years after Hylan left office. But, early plans for that service didn’t have it chugging up Central Park West. Instead, those plans foresaw a subway in Central Park itself.

The New York Times reported on July 24, 1920, that “the course of the proposed line is under 8th Avenue, from the southern terminal of that thoroughfare to 59th Street, thence under Central Park to a connection with the Lennox Avenue tracks at 110th Street.”

While most plans for the expansion of the subway were met with laudatory fanfare, (the Times noted breathlessly in September 1920 that a “$350,000,000 plan for subway routes has been completed,” and the new lines “will radiate from the heart of Manhattan, and touch every section of the city.”) the plan for a subway through Central Park had preservationists and reformers up in arms.

The Municipal Art Society led the charge. At the helm of the Society’s campaign to keep the subway out of Central Park, was Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes. Stokes hailed from the illustrious Phelps Stokes family, which had made its fortune in banking, real estate and railroads, and lived in luxury at 229 Madison Avenue.

In spite of their privilege, or perhaps because of it, the Phelps Stokes family was deeply involved in, housing reform, preservation, and philanthropy. For his part, Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, an architect, designed the University Settlement, at 184 Eldridge Street, the first settlement house in the nation. He went on to co-author the 1901 Tenement House law of 1901, and head The Municipal Art Commission (now the Public Design Commission) under Fiorello La Guardia, overseeing the WPA Mural Program in New York City. He also served as a trustee of the New York Public Library, and as honorary vice president of the Community Service Society of New York.

In 1919, The Municipal Art Society put him in charge of its campaign to restore and maintain Central Park. Stokes had several intimate connections to the park: Calvert Vaux himself had taught a young Stokes to row in the park; in the course of his research, Stokes unearthed Olmstead and Vaux’s original Greensward plan for the park, long thought lost; Stokes had even overseen the publication of Olmstead’s personal papers. With these plans and papers in hand, Stokes and the Municipal Art Society were able to halt countless proposals that would have encroached upon the park.

The Municipal Art Society bulletin even reminded readers that “among the dozens of projects which it has been proposed over the last decade to erect in Central Park, we may recall a municipal broadcasting station, taxi-cab stands, an open-cut subway, and a municipal art center, ” all of which the Society opposed.

They were joined in their opposition by a host of other city arts groups. For example, in January 1920, the Fine Arts Federation, which represented artists, architects, sculptors and landscape architects, passed a resolution against proposals that would take away park space for buildings or projects unrelated to the park itself. The Fine Arts Federation held that “people who see no beauty in the Park, and always feel that it is a waste of space, are ready with their plans for using it.”

Regarding the proposed amenities in the park, of which the subway was a large part, the Federation called, “Let us who love and enjoy the park because it is not waste space, but full of sensual beauty and delight, join in finding some other more convenient place for these admirable features, which we, too, are ready to enjoy, and for which we feel the need as keenly as anyone.”

But, it wasn’t just artistic objection that kept the park pristine. It was legal action. A suit brought by the Council for Parks and Playgrounds culminated in a sweeping decision from the Court of Appeals in June 1920 holding Central Park must “be kept free of intrusion of any kind which would interfere in any degree with its complete use for park purposes.”

Central Park Sheep’s Meadow via WikiCommons

And so the park was saved. But, a half-century later, a subway tunnel did make its way under Central Park. The tunnel, built in the 1970s, runs between 57th Street/7th Ave and Lexington Avenue/63rd Street and remained an unused ghost tunnel for decades until it found permanent use as a connection to the Second Avenue Subway. Today, the Q train travels through the long-abandoned tunnel as it makes its way to Second Avenue.

RELATED:

- Ghost tunnel under Central Park will reopen along with Second Avenue Subway

- MAP: Here’s what the NYC subway system looked like in 1939

- NYC’s first subway line moved passengers just one block

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.