Frank Lloyd Wright had a plan to build a ‘city of the future’ on Ellis Island

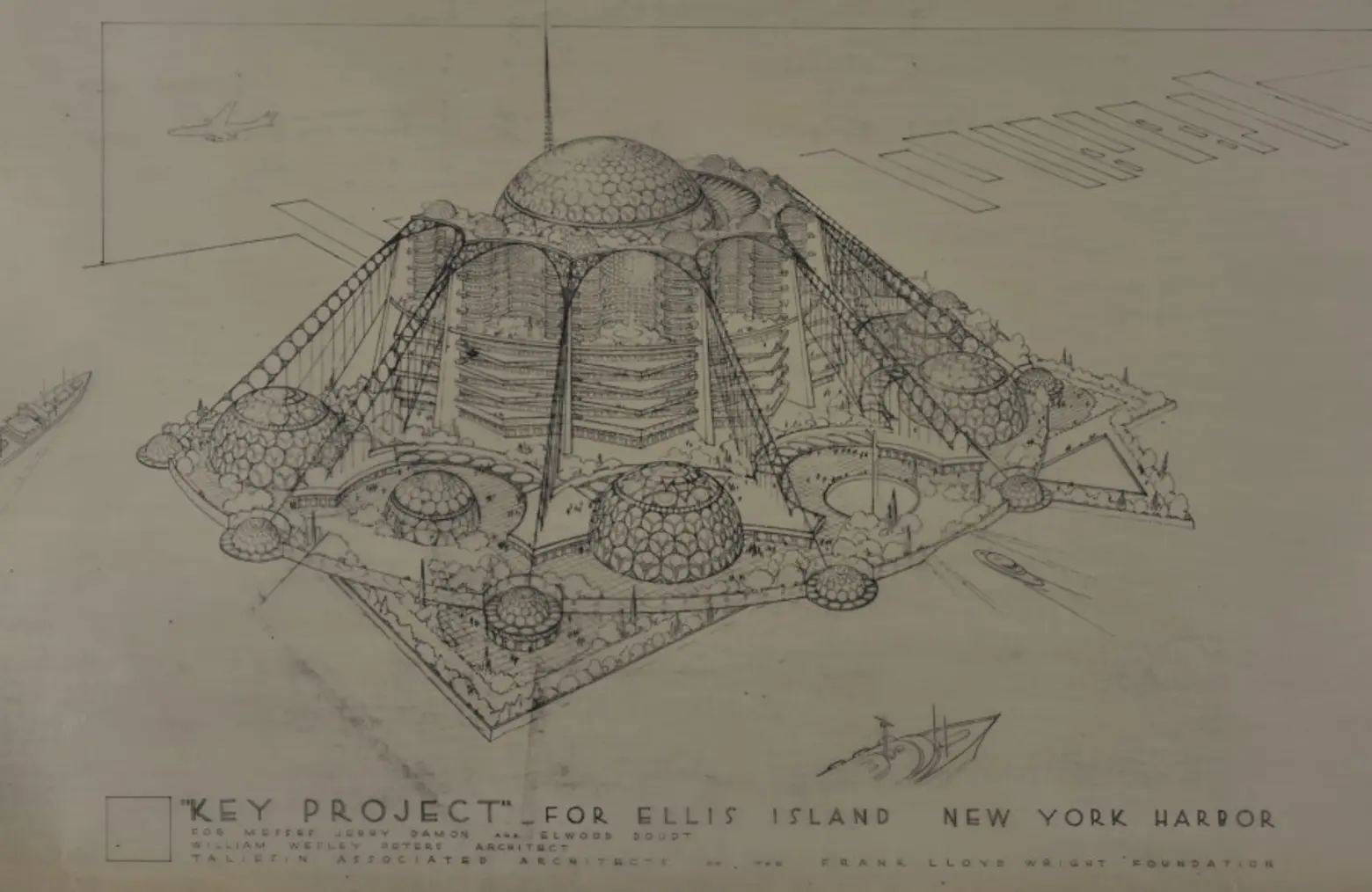

Frank Lloyd Wright/TAA drawing of Key Project for Ellis Island. Credit: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Ellis Island, well known as the processing center for millions of American immigrants until 1954, has figured heavily in the nation’s history; once the center was closed and neither of its current owners, the states of New York and New Jersey, knew of an alternative for its re-use, the island was offered for sale. Among the bidders for the 27-acre site were a pair of young NBC executives whose idea included breathtaking plans conceived by none other than Frank Lloyd Wright. According to Metropolis, Wright’s idea supported the media execs’ vision for “an entirely new, complete, and independent prototype city of the future.”

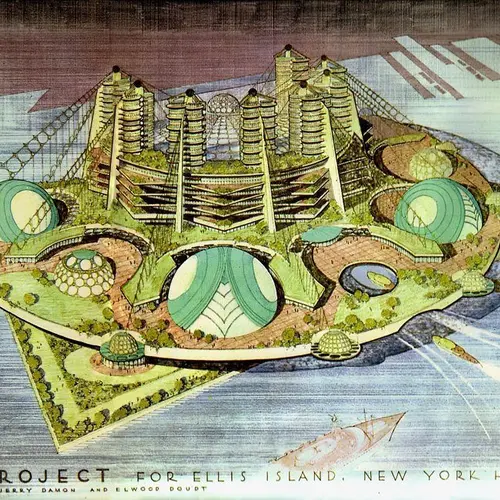

Key Project for Ellis Island, Taliesin Associated Architects drawing, 1962. Courtesy The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). Copyright © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. Via Metropolis.

NBC radio and television executives Elwood M. Doudt and Jerry Damon had a monumental plan for the island; in early spring of 1959, Doudt contacted Wright at Taliesin West to elaborate this vision, and to inquire whether the architect might be interested in designing it. The answer: “Your Ellis Island project is virtually made to order for me.” Wright arranged a meeting at his apartment in the Plaza to discuss the plans. He died just days before the meeting had a chance to happen.

However, Damon was notified by another architect from Wright’s Taliesin Associated Architects (TAA) that the basic conceptual plans for the island had already been created. Wright’s son-in-law and TAA principal William Wesley Peters described the project Wright had been working on as “a cable-supported structure extending radially from central towers,” but said no drawings had been produced.

The two developers met with Peters several times, which resulted in a complete set of drawings for the project, dubbed “Key Project,” because the Ellis Island represented the key to freedom and opportunity. In their bid for the property, Damon and Doudt offered a totally self-contained futuristic city, custom-designed by the late Frank Lloyd Wright and TAA.

Privately financed construction costs were estimated to be about $100,000,000 (about $810,374,172.19 today). The Museum of Modern Art featured one of the Key Project images in a 1962 exhibit, The Drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright, captioned “A semi-circular terrace is superimposed on the existing rectangular island; apartment and hotel towers rise at the back, and domed theatres and shops are set into the terrace park.”

Though at $2.1 million, Damon and Doudt’s bid for Ellis Island in 1962 beat all previous offers, it was rejected along with the development schemes of a host of other bidders. In 1963, New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner proposed that the best use for the island was as a site for a museum park and memorial.

Also missing from today’s Ellis Island: Innovative architect Philip Johnson was hired to create a National Immigration Museum and Park plan for the island. Johnson’s plans included a 130-foot high truncated cone, to be called the “Wall of Sixteen Million,” where visitors could walk around the structure on ramps that wound around the inner and outer faces of the cone (think an inverted Guggenheim). Photographic reproductions of original ships’ manifests listing the names of the sixteen million immigrants who had passed through the island would line the walls. The Johnson plans also called for an off-shore restaurant, a picnic grove, a Manhattan skyline viewing pyramid and a ceremonial field. The public and the press hated the plan, calling it “outrageous,” and, more importantly, the price for its implementation was prohibitive. The plan was scrapped, as were many more in the years to come, with little progress seen until an eight-year renovation was begun in 1982.

[Via Metropolis]

RELATED:

Get Inspired by NYC.

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

It all turned out for the best, didn’t it.