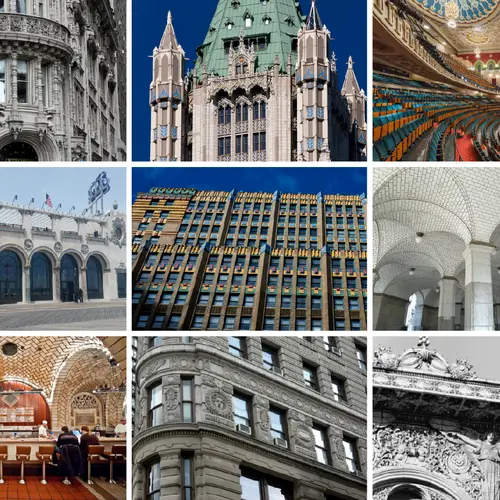

10 of NYC’s most impressive Terra-cotta buildings

Terra-cotta, Latin for “fired earth,” is an ancient building material, made of baked clay, first used throughout early civilizations in Greece, Egypt, China the Indus Valley. In more modern times, architects realized that “fired earth” actually acts as a fire-deterrent. In the age of the skyscraper, terra-cotta became a sought-after fire-proof skin for the steel skeletons of New York’s tallest buildings. In the early part of the 20th century, the City’s most iconic structures were decked out in terracotta.

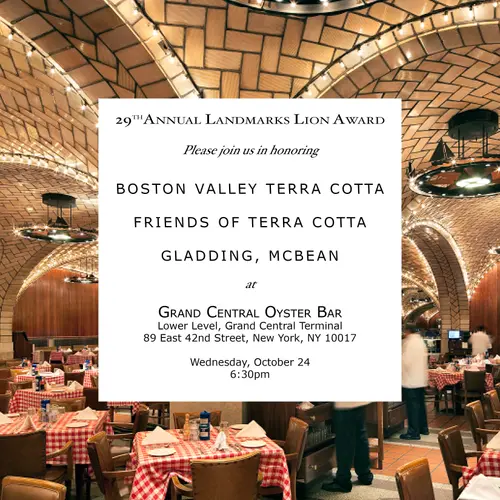

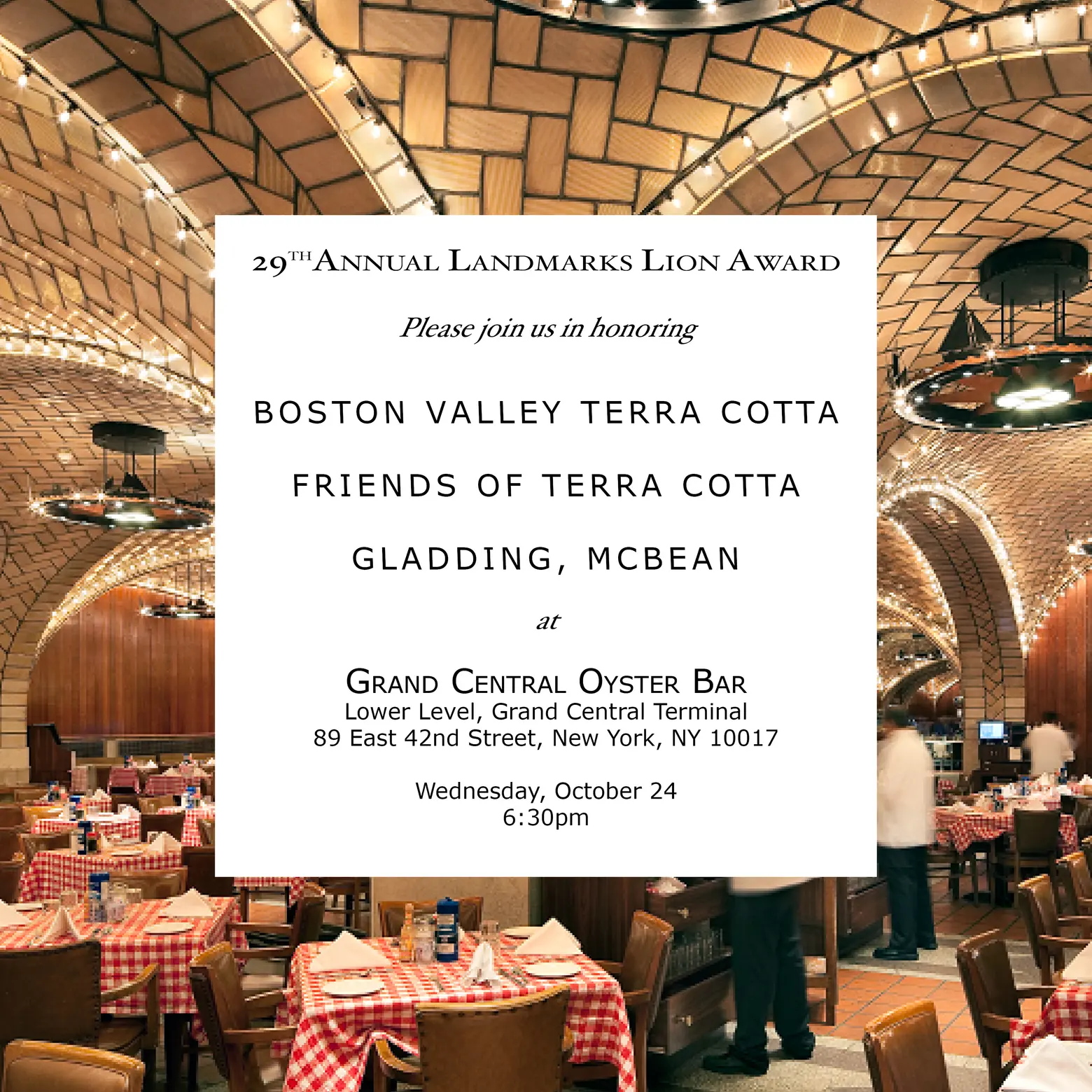

You’ll find terra-cotta on famous facades from the Flatiron to the Plaza, but the material often flies under the radar of pedestrians and architecture buffs alike because it can mimic other materials, like cast-iron or carved wood. Now, this long-underappreciated material is getting its due. On October 24th, the Historic Districts Council will present its annual Landmarks Lion Award to the terra-cotta firms Boston Valley Terra Cotta and Gladding, McBean, which work to keep terra-cotta alive worldwide, and to the preservation organization Friends of Terra Cotta, which has worked to preserve New York’s architectural terra-cotta since 1981. The ceremony will take place at Grand Central’s Oyster Bar, under the magnificent Guastavino terra-cotta ceiling recently restored by Boston Valley Terra Cotta. Fired up about finding “fired earth” around town? Here are 10 of the most impressive examples of New York terra-cotta!

1. Flatiron Building

Rising 22 stories above 23rd Street, and anchoring the northern end of the Ladies’ Mile Historic District, the Flatiron Building features glazed terra-cotta. When the building opened in 1902, modern artists saw in its distinctive shape their own kindred spirit. The photographer Alfred Stieglitz mused, “it appeared to be moving toward me like the bow of a monster ocean steamer – a picture of a new America still in the making.”

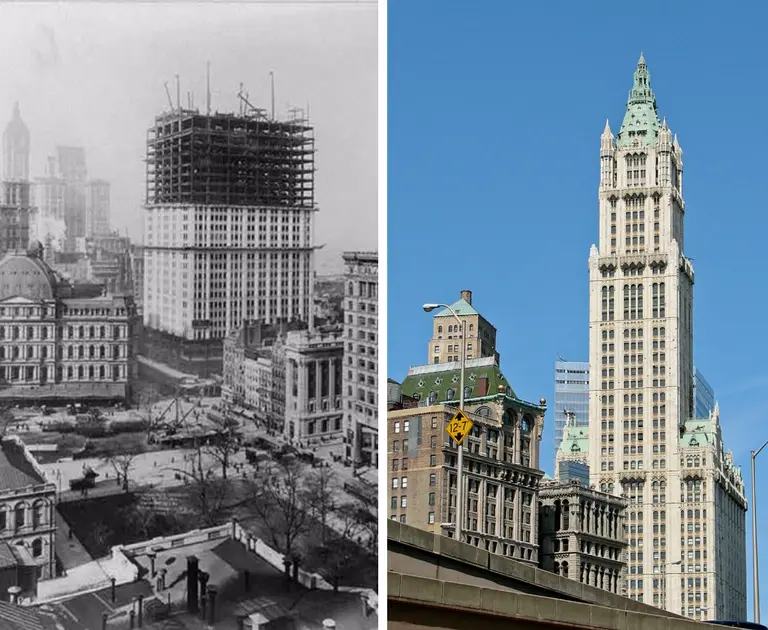

2. The Woolworth Building

Via Wiki Commons

The crown of the Woolworth Building might be covered in gold leaf, but the tower’s exterior is clad in limestone-colored terra-cotta. Cass Gilbert’s 1913 neo-Gothic masterpiece, restored by Boston Valley Terra Cotta in 2015, set an architectural standard for 17 years as the tallest building in the world and is still the world’s tallest terra-cotta structure. While the “Cathedral of Commerce” towered over the city, its tenants made towering contributions to 20th-century history. For example, Columbia Records cut what are considered to be the first Jazz records in a recording studio in the Woolworth building in 1913; in the 1940s the Woolworth Building helped the Manhattan Project stay true to its name: The spy Klaus Fuchs worked on enriching Uranium inside the building.

3. The Bayard-Condict Building

The Bayard-Condict Building, a favorite of Friends of Terra Cotta founder Susan Tunick, opened in 1899 at 65-69 Bleecker Street. It is the only building in New York City designed by the great Chicago architect Louis Sullivan. As the first American architect to work in a non-historic, modern architectural style and the first to “solve the design problem of the tall building,” Sullivan led the development of 20th-century modern architecture in both the United States and Europe. He believed that a skyscraper “must be every inch a proud and soaring thing.” The Bayard-Condict building is such an elegant distillation of his design principles, that the New York City Landmarks Commission calls it “the most significant building using skyscraper techniques in New York City.”

The Landmarks Commission also holds that the building is unique within the city’s architectural history because “it is the only skyscraper of the period that frankly expresses its structural components in the manner of the Chicago School. There is no attempt to make the terra-cotta look like a masonry building, to deny the nature of the material. Thus, it is the first truly modern skyscraper in New York City.”

The white terra-cotta that makes the Bayard-Condict building so modern covers the entire structure. Sullivan was one of the first architects to make use of terra-cotta facing, and the Bayard Building was the first structure in New York to feature terra-cotta curtain walls. The building’s terra-cotta ornamentation was both molded and hand-carved to create a play of light and shade across the façade. In 2000, the building was restored, and 1,300 of its 7,000 terra-cotta tiles were removed, repaired, and reinstalled.

4. The Grand Central Oyster Bar

Grand Central’s storied Oyster Bar opened in 1913, the same year as the terminal itself, in the heyday of long-haul train travel. Known for some of the freshest seafood in New York, the Oyster Bar also sports some of the finest tile-work. The bar’s vaulted ceiling glistens with Guastavino Tile, a system of interlocking terra-cotta tiles that create graceful self-supporting arches. The tiles, famously fire-resistant, were virtually the only part of the restaurant that did not burn when a fire swept through the bar in 1997. During the conflagration, thousands of the tiles fell to the floor. It took nearly six months to match replacement tiles to the originals and close to a full year before the striking ceiling was fully restored.

5. Childs Restaurant

Via NYCEDC

Via NYCEDC

Childs Restaurant launched in Manhattan in 1889 as one of the nation’s first dining chains. Serving up 5 cent eggs and 10 cent corn beef hash, Childs provided affordable food in clean and comfortable surroundings. The highly successful chain grew to over 125 locations in the 1920s and employed some of the nation’s most sought-after architects to design their facilities (William Van Alen, best known for the Chrysler Building, designed several of Childs’ locations.)

But no Childs Restaurant was as opulent as the chain’s flagship on the Coney Island Boardwalk. Dennison & Hirons’ 1923 nautical fantasia combines Spanish Colonial Revival architecture with maritime motifs and technicolor terra-cotta to achieve some serious sea-side splendor. The terra-cotta, originally manufactured by the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company, features fish, seashells, ships, and even a likeness of Neptune, god of the sea.

The restaurant flourished until the early 1950s when Coney Island fell into disfavor and disrepair. Later, a candy manufacturer moved into the building. In 2002, the former Childs Building came before the Landmarks Commission, and advocates from Friends of Terra Cotta, the Municipal Art Society, the Landmarks Conservancy, and the Historic Districts Council all advocated for its designation. In 2017, the building’s whimsical, technicolor terra-cotta got a loving restoration by Boston Valley Terra-Cotta. Today, the building is home to the new concept restaurant, Kitchen 21, and is serving Coney Island crowds once again.

6. 2 Park Avenue

Via Jeffrey Zeldman on Flickr

Speaking of technicolor terra-cotta, Ely Jacques Kahn’s 2 Park Avenue, opened 1928, features a veritable tapestry of brightly hued blocks. For the design, Kahn collaborated with ceramist Leon Victor Solon to adorn the building with magenta, ochre, black, and azure terra-cotta. Using terra-cotta allowed Kahn, one of the city’s foremost modern architects, to apply sumptuous Art Deco styling to a more simple office-loft building.

The building’s bright terra-cotta ornamentation was paramount to creating New York’s striking early 20th-century skyline. The Landmarks Commission holds, “2 Park Avenue was one of the important late 1920s buildings that helped create the visually lively and iconic city of the early 20th century.” Khan himself took offices in the building, and it was here that he served as an architectural mentor to Ayn Rand, who drew on the experience while writing The Fountainhead.

7. The Plaza Hotel

Via Christian on Flickr

Henry Hardenberg, who also designed the Dakota, may have designed the Plaza as a French Renaissance Chateau, but its terra-cotta ornamental details are all-American. In fact, they were manufactured right here in New York City. The New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Company, the only terra-cotta manufacturer in New York City, produced terra-cotta from its plant at 401 Vernon Avenue in Long Island City. The plant operated from 1886-1932, while the company outfitted over 2,000 buildings in the United States and Canada. The Plaza and Carnegie Hall were among its most famous commissions.

8. Alwyn Court

Via Wiki Commons

Just blocks from the Plaza, at 180 West 58th Street, another terra-cotta clad French Renaissance building rises above midtown. It’s Alwyn Court, completed in 1909 and landmarked in 1966. The LPC calls Alwyn Court the finest example of a terra-cotta-faced apartment building in New York City.

While most other apartment buildings constructed at the same time featured a limestone base and a relatively plain shaft with limited decoration, Alwyn Court is one of the city’s most highly decorated addresses. Working in stone would have made such elaborate detail prohibitively expensive, but terra-cotta lent itself to sumptuous decoration since the cast clay could be molded, and each mold could be used repeatedly. Indeed, architects Harde and Short were able to complete the building for under $1 million. While the building was a relatively inexpensive commission, its ornamentation telegraphed richness: details include the crowned salamander, symbol of Francis the First, King of France.

9. Manhattan Municipal Building

Via Wiki Commons

Manhattan’s Municipal building towers over 1 Center Street as the first skyscraper designed by the venerated firm McKim, Mead and White. Completed in 1914, it remains one of the largest office buildings in the world, housing over 2,000 employees in nearly one million square feet of office space. The building, both gracious in limestone and gargantuan in scale, stands as a testament to the city’s physical and technological growth.

As the city’s population soared in the second half of the 19th century, municipal services and agencies began to overwhelm the space available in City Hall. By 1884, the City was renting office space as far north as Midtown to house its burgeoning municipal agencies. To meet the demand without paying rent, the City began soliciting proposals for what would become the Municipal Building in 1888. The consolidation of all 5 boroughs into Greater New York in 1898 made the project even more meaningful: the Municipal Building would represent the newly interconnected New York City.

Via Wiki Commons

As the first building to incorporate a subway station into its base, the Municipal Building truly reflected that inter-connected identity. And it’s in the building’s fine, vaulted, ground-floor subway entrance that you’ll find its terra-cotta touches. The Municipal Building’s subway arcade is based on the Palazzo Farnese in Rome and features the same Guastavino that adorn the Oyster Bar.

10. New York City Center

Via The restored facade, via Ennead Architects

The Neo-Moorish New York City Center, originally known as Mecca Temple, was built in 1923 as a meeting place Ancient Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, also known as Shriners. The Shriners were a 19th century variant of the Freemasons, who traced their heritage to Order of the Mystic Shrine founded at Mecca in 698 AD. The building’s architect, Harry P. Knowles, was himself a member of the Order, and his temple stands as one of the finest examples of Fraternal architecture in New York City.

The building’s remarkable mosaic dome is a masterpiece of polychrome terra-cotta. The dome is as functional as it is beautiful: it houses an integral part of building’s ventilation system, an 8-foot wide exhaust fan, which was indispensable when the building opened since smoking was permitted in the auditorium.

Following the Crash of ’29, the Shriners could no longer maintain the building, and it became City property. In 1943, it became Manhattan’s first performing arts center, and on opening night, Mayor LaGuardia himself wielded the baton to conduct the National Anthem during a special performance by the New York Philharmonic.

+++

The Historic District Council’s Landmarks Lion Award will take place on Wednesday, October 24th at 6:30pm at the Grand Central Oyster Bar. For more details on the event and to purchase ticktes, click here >>

RELATED:

- Terra Cotta in New York City: Beautiful Buildings Adorned in Ceramic

- Terra cotta figures that adorned building demolished for One Vanderbilt construction seek a new home

- A Behind the Scenes Look at How SHoP’s Stunning Facade at 111 West 57th Street Will Come to Life

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.