13 things you didn’t know about the Woolworth Building

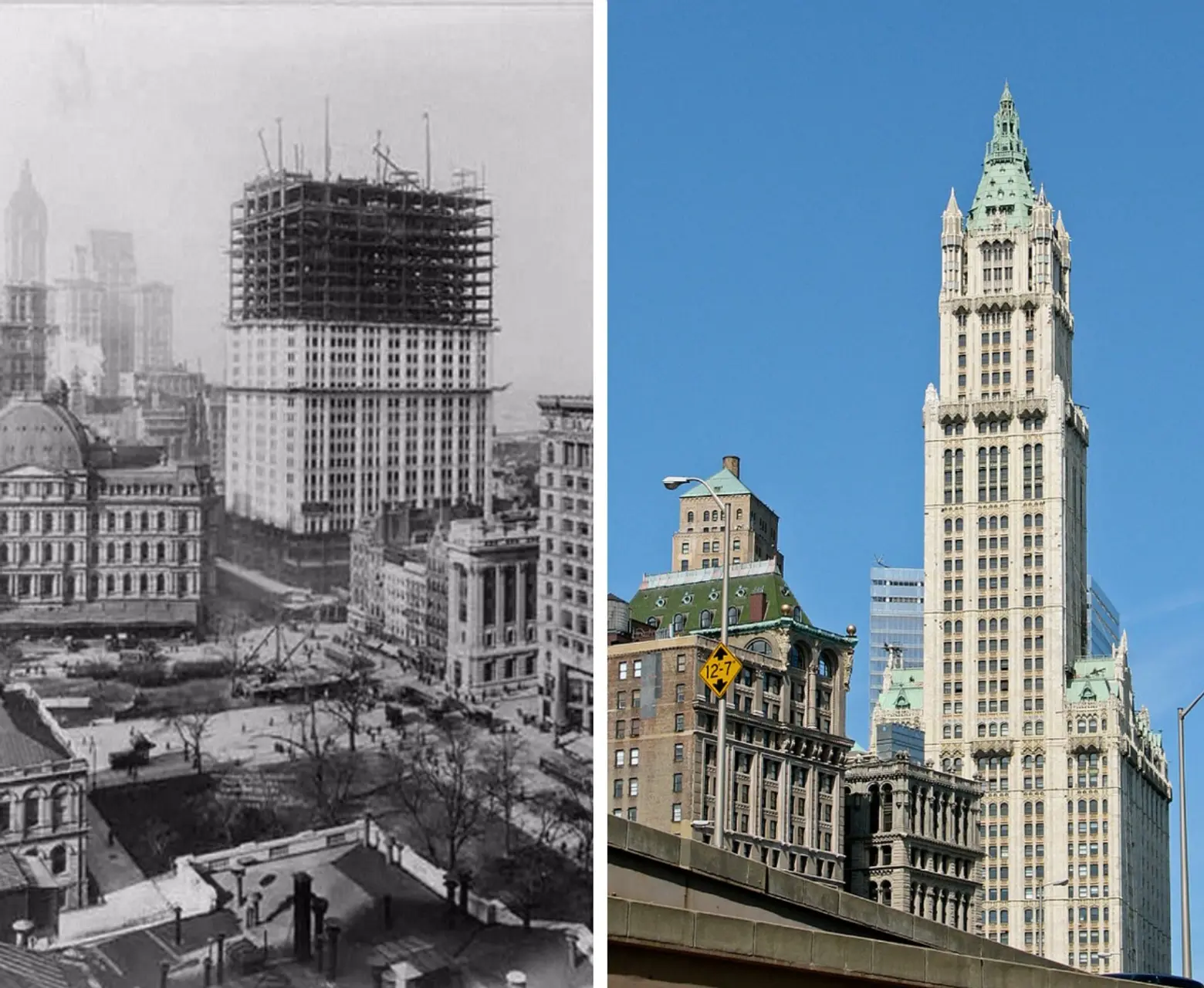

The Woolworth Building, then and now. L: Image courtesy of Library of Congress via Wiki cc; r: Image Norbert Nagel via Wiki cc.

When the neo-Gothic Woolworth Building at 233 Broadway was erected in 1913 as the world’s tallest building, it cost a total of $13.5 million to construct. Though many have surpassed it in height, the instantly-recognizable Lower Manhattan landmark has remained one of the world’s most iconic buildings, admired for its terra cotta facade and detailed ornamentation–and its representation of the ambitious era in which it arose. Developer and five-and-dime store entrepreneur Frank Winfield Woolworth dreamed of an unforgettable skyscraper; the building’s architect, Cass Gilbert, designed and delivered just that, even as Woolworth’s vision grew progressively loftier. The Woolworth Building has remained an anchor of New York City life with its storied past and still-impressive 792-foot height.

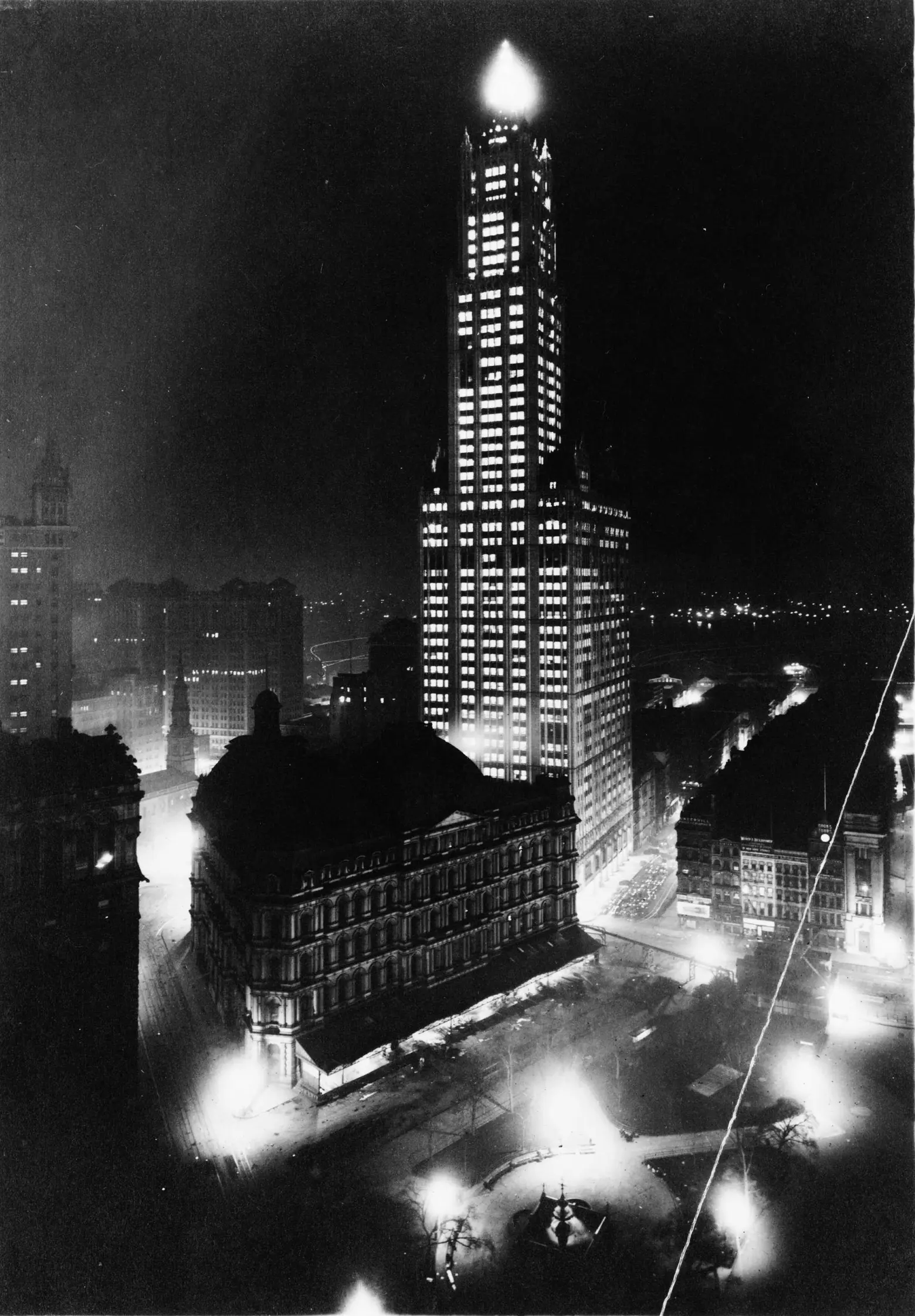

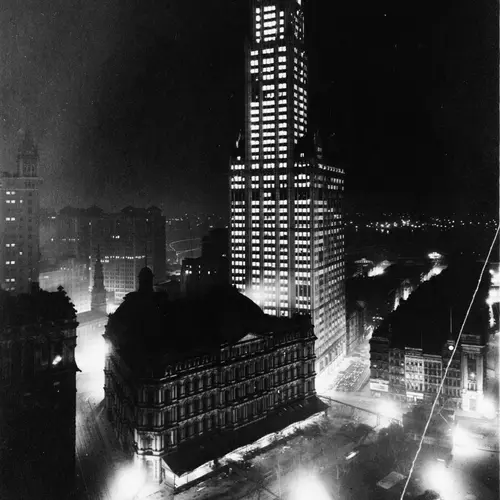

Image via Wikimedia cc.

Image via Wikimedia cc.

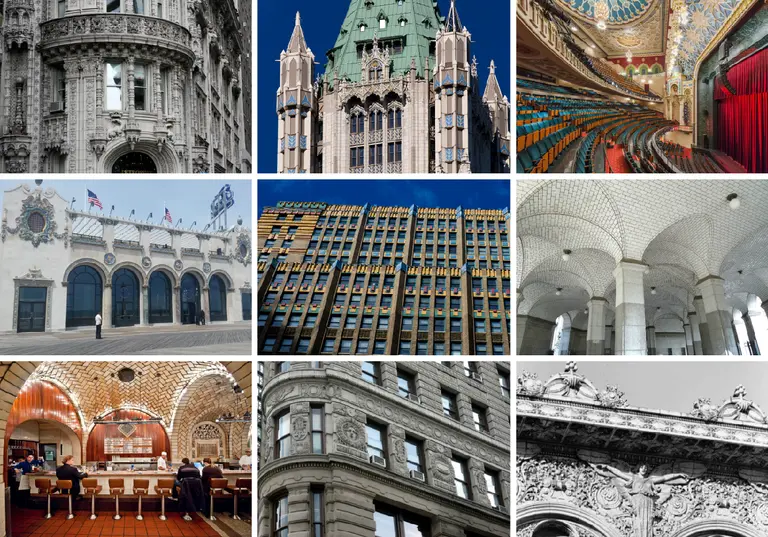

The building has been a National Historic Landmark since 1966 and a New York City-designated landmark since 1983. Its tower sparkles with mosaics, stained-glass, and golden embellishments, and its halls and walls are steeped in fascinating historic facts and lesser-known secrets.

In the 21st century, the top 30 floors would be converted to luxury apartments with a 2 Park Place address and a nine-story penthouse listed for a record $110 million. And the recent creation of 32 condominium residences within its historic walls is among the city’s most ambitious residential conversions.

1. Reaching for the sky: The Woolworth Building was the tallest building in the world from 1913 to 1930, with a height of 792 feet. More than a century after its construction, it remains one of the 100 tallest buildings in the United States.

2. An entrepreneur’s ambitions–and an architect’s commitment: With a decisive financial stake in the building’s development, Woolworth commissioned Cass Gilbert to design it after admiring his work on the nearby Broadway–Chambers Building and 90 West Street. Woolworth also wanted the new tower to incorporate the Gothic style of the Palace of Westminster in London.

Gilbert’s original directive was to design a standard commercial building, 12- to 16-stories high. Then came Woolworth’s desire to surpass the nearby New York World Building, which stood 20 stories and 350 feet high. By September 1910, Gilbert’s designs showed a taller structure, with a 40-story tower on Park Place next door to a 25-story annex. The now-550-foot-tall building had become a 45-story tower as tall as the Singer Building, Lower Manhattan’s tallest building at the time and one that was frequently praised on Woolworth’s European trips when talk turned to Manhattan towers.

Three months later, Woolworth requested the building rise to 620 feet–8 feet taller than the Singer Building. The newest design took the form of a 45-story tower rising 625 feet. Woolworth wanted to confer upon visitors bragging rights to visiting the world’s tallest building.

The new plans had the building closing in on the 700-foot height of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower, at the time the tallest building in New York City and the world. In December of the same year, Woolworth tasked a team of surveyors with a measurement that would enable his skyscraper to be taller. He ordered Gilbert to design a building that reached 710 or 712 feet.

To construct the larger base required by a taller tower, Woolworth bought the remaining frontage on Broadway between Park Place and Barclay Street. In January of 1911, a New York Times story reported that Woolworth’s building would rise 750 feet from ground to tip. Construction officially began on November 4, 1910, with the excavation by The Foundation Company.

4. Dinner in the clouds: When the Woolworth Building officially opened on April 24, 1913, it was the site of “the highest dinner ever held in New York.” A glittering dinner was hosted by Woolworth on the 27th floor, where the 900 VIP guests included businessmen Patrick Francis Murphy and Charles M. Schwab, Rhode Island Governor Aram J. Pothier, US Senator from Arkansas Joseph Taylor Robinson, Ecuadorian minister Gonzalo Córdova, New York Supreme Court Justices Charles L. Guy and Edward Everett McCall, banker James Speyer, writer Robert Sterling Yard and dozens of congressmen who arrived by way of a special train from Washington, DC.

5. And friends in high places: At exactly 7:30 p.m. EST, then-President Woodrow Wilson officially turned on the building’s lights by pushing a button in Washington, D.C.

Woolworth Tower Residences pool rendering courtesy of Alchemy Properties

6. Fit for an emperor: Woolworth reveled in the glory of the new tower, and the personal quarters he kept there were appropriately opulent, including a 40th-floor Renaissance-style apartment, private suites on the 25th floor and an “Empire Room” office on the 24th floor that reflected the millionaire’s obsession with all things related to Napoleon, complete with Napoleonic palace decor, memorabilia, and a replica throne chair fit for an emperor.

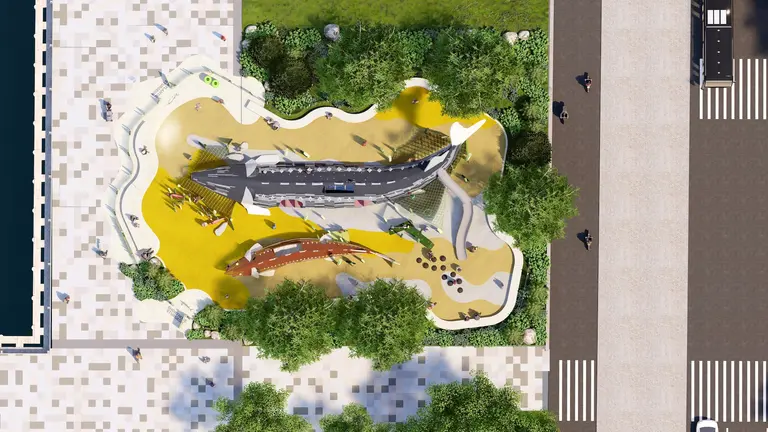

7. A secret basement pool: Below ground, Woolworth commissioned a private basement swimming pool. In the many years that followed Woolworth’s reign over the property, the abandoned pool was among its most compelling secrets, only viewable during private tours. In recent years the pool has been restored to its original glory–and its original luxurious intent.

Image: Johannes Janocha via Wikimedia cc.

8. Faces in the architecture: A 2009 photo series by Carol M. Highsmith features the mysterious faces hiding throughout the building’s halls and corners. Though they may seem mystical and enchanted, many of these “faces in the architecture” represent the real-life laborers involved in its construction; they even include one of the architects and Frank W. Woolworth himself. Other faces represent, from south to north, the four continents.

Image Cc2723 via Wikimedia cc.

9. An artistic pedigree: The arabesque tracery patterns in etched steel on the gold-plated background of the elevator doors in the building’s lobby were designed by Tiffany Studios.

10. Wartime austerity: As a frugal contrast to the building’s air of no-holds-barred opulence, it joined the rest of the nation in conservation during the two World Wars. During World War I, only one of the Woolworth Building’s then-14 elevators was used; lighting fixtures in hallways and offices were turned off, which resulted in a 70 percent energy reduction to meet wartime requirements. The same policies were put in place again during World War II: 10 of the building’s 24 elevators were disabled in 1944 due to a coal shortage.

11. Tenants old and new: The Woolworth Building’s lengthy list of tenants tells a tale of the city’s growth and the world’s advancement throughout a century. Columbia Records was among the building’s original tenants, with a recording studio in the skyscraper. Columbia used the space to make what is considered one of the first jazz recordings by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. The inventor Nikola Tesla had an office in the Woolworth Building in 1914; he was evicted after a year because he wasn’t able to pay his rent. Scientific American magazine moved in in 1915.

The Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company occupied the southern half of the 18th floor. Other early tenants included the American Hardware Manufacturers Association headquarters, the American Association of Foreign Language Newspapers, Colt’s Manufacturing Company, Remington Arms, Simmons-Boardman Publishing headquarters, the Taft-Peirce Manufacturing Company, and the Hudson Motor Car Company.

In the 1930s, prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey investigated racketeering and organized crime in Manhattan while he kept offices that occupied the building’s entire–heavily guarded–14th floor. As another top-secret sign of the times, during World War II the Kellex Corporation, part of the Manhattan Project, was based in the Woolworth Building.

Photo of SHOP Architects’ offices in the Woolworth Building by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft.

21st-century tenants also represent the times: Starbucks opened a 1,500-square-foot shop on the building’s ground floor in 2003. Additional modern-day tenants include the New York City Law Department, Joseph Altuzarra’s namesake fashion brand, Thomas J. Watson’s Watson Foundation, the New York Shipping Exchange, architecture, and design firm CallisonRTKL. In 2013, ShOP architects moved the company’s headquarters to the building’s entire 11th floor, occupying 30,500 square feet of space.

12. Homage: Built in 1924, the Lincoln American Tower in Memphis, Tennessee, is a one-third-scale replica of the Woolworth Building.

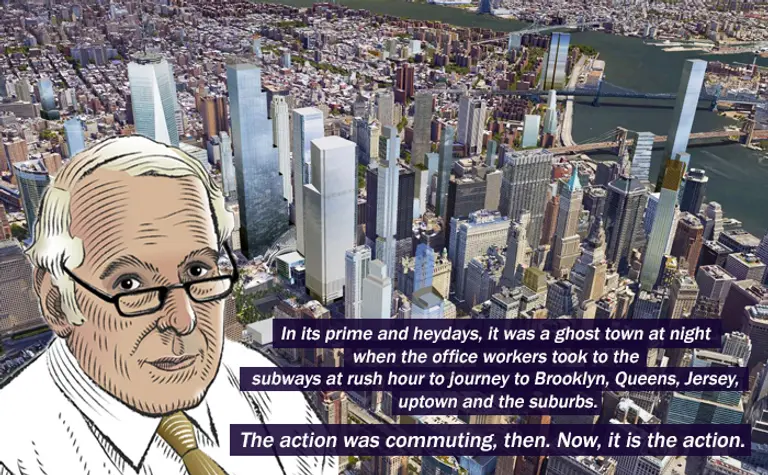

The Pinnacle: Rendering courtesy of Williams New York.

13. The pinnacle of luxury: The top 30 floors were sold to a residential developer in 2012 and the building’s life as a luxury residence began anew, though the building’s lower floors remain in use by office and commercial tenants. During the building’s first 21st-century foray into luxury living, the most expensive penthouse in the city topped the Woolworth Building. The jaw-dropping sky-palace within its iconic copper pinnacle was listed for $110 million in 2014.

A new era of Manhattan living: The building’s most recent renovation has turned out to be the most impressive of all, including many restorations and changes to the building’s interior. A new private lobby was also built for residents and the coffered ceiling from F.W. Woolworth’s personal 40th-floor office was relocated to the entryway. As 6sqft reports,

The jewel in the crown, so to speak, among these trophy properties is The Pinnacle, a 9,680-square-foot home perched 727 feet above New York City in the building’s famous crown. This lofty residence spans floors 50 to 58, with a 408-square-foot private observatory terrace. Priced at $79 million–a considerable chop from its original price of $110 million when it first arrived on the market in 2017–the peerless penthouse is being offered as a white box, with award-winning architect David Hotson on board to develop the interior design.

Image courtesy of The Corcoran Group.

The building’s new residential interiors were designed by celebrated designers Thierry Despont and Eve Robinson with custom cabinetry, precision appliances and fabulous fixtures and fittings. Each unit even gets private space in a wine cellar–and access to the restored private basement pool. The 30th floor hosts a state-of-the-art fitness facility, while floor 29 hosts the Gilbert Lounge, named after the building’s architect.

RELATED:

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

I notice a dragon and snake face in the outside of the Woolworth building, hidden is that also .a part of the artwork outside the building they wanted us to figure out. Or it’s part of the story of the building