Radio Row: A tinkerer’s paradise and makerspace, lost to the World Trade Center

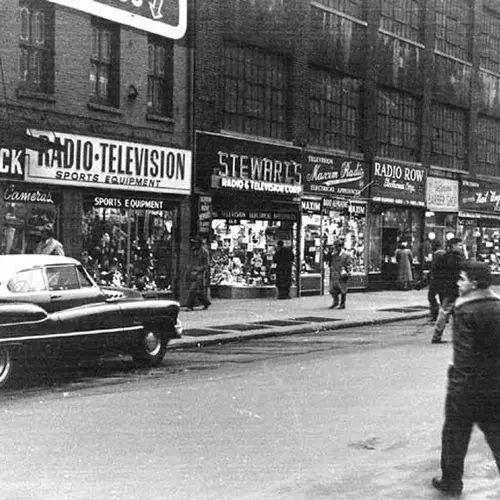

Radio Row, looking east along Cortlandt Street towards Greenwich Street, by Berenice Abbott Image via NYPL.

Before the internet and before television, there was radio broadcasting. The advent of radio at the turn of the 20th century had major repercussions on the reporting of wars along with its impact on popular culture, so it’s not surprising that a business district emerged surrounding the sale and repair of radios in New York City. From 1921 to 1966, a roughly 13-block stretch going north-south from Barclay Street to Liberty Street, and east-west from Church Street to West Street, was a thriving small business stronghold known as Radio Row.

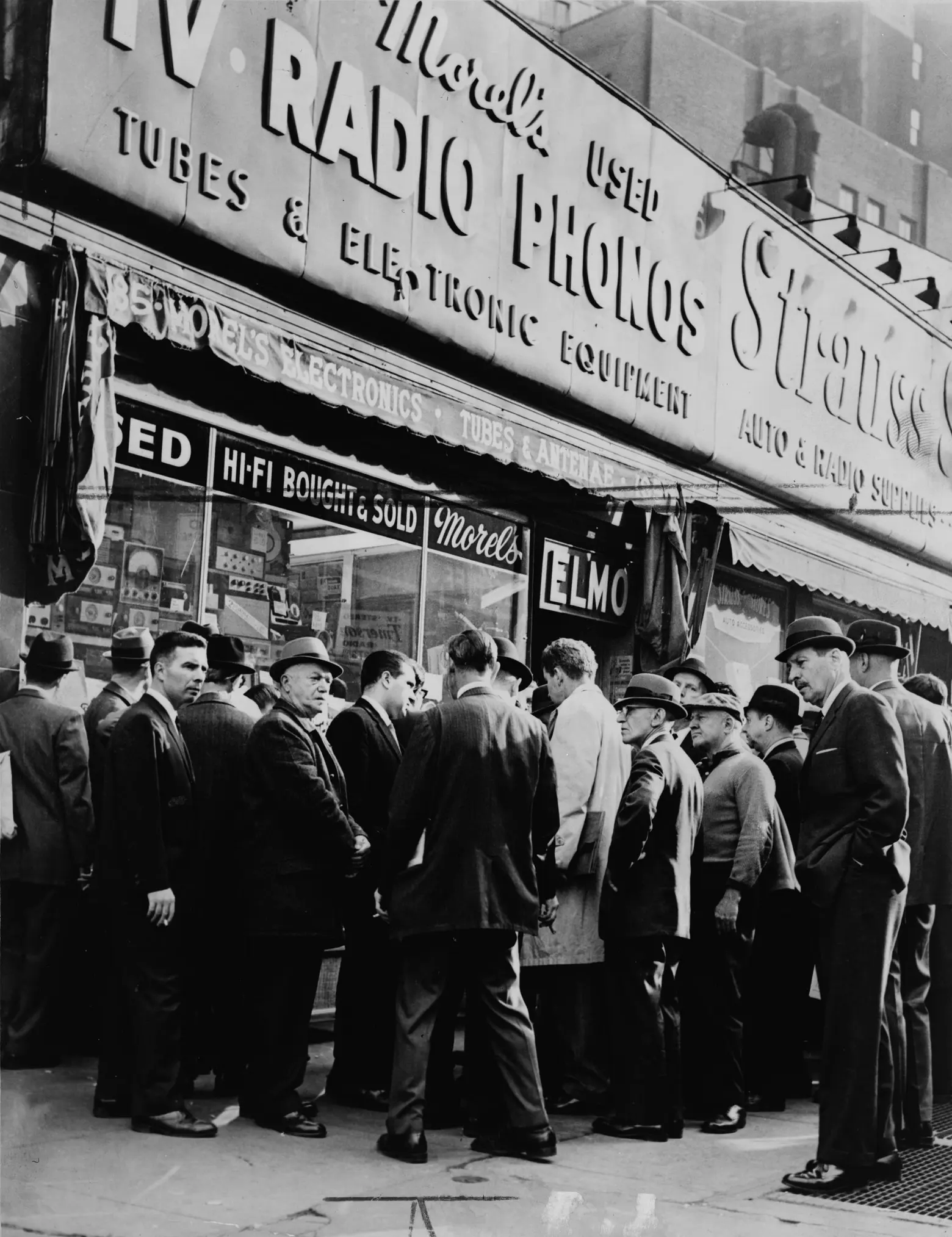

At its peak, more than 300 businesses and over 30,000 employees were located there. Photos and first-person observation all speak to the clutter and home-grown nature of the neighborhood, with The New York Times calling it a “paradise for electronics tinkerers.” Every storefront and shop interior was jam-packed floor to ceiling with parts. Other enterprising businessmen competed by displaying goods on the street. And more than just radios, it was a destination for surplus including sheet metal and brass–basically anything one would need to create something. It was very much a neighborhood-size Makerspace that spilled out into the streets.

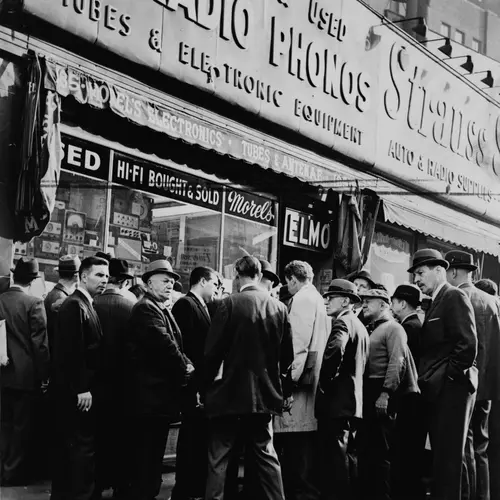

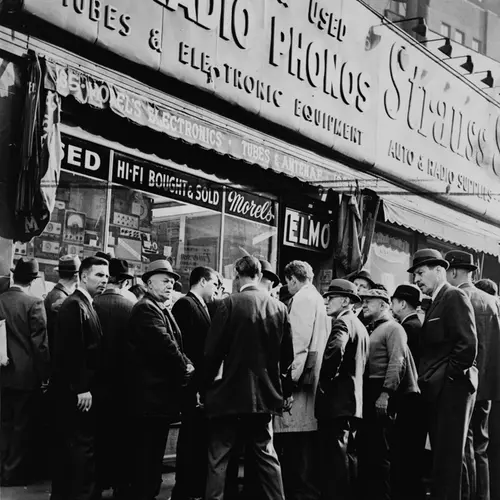

Crowd gathers in Radio Row to hear news of JFK assassination. Via Wiki Commons.

Crowd gathers in Radio Row to hear news of JFK assassination. Via Wiki Commons.

Of course, this lack of order made it a prime target for redevelopment. (A modern day comparison would be Willets Point in Queens, home to a major small-business auto repair industry being evicted in the name of environmental degradation and middle-class big box development.)

The first proposal for a World Trade Center came pre-WWII in 1943. And in the 1950s, David Rockefeller, chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank, became involved with the World Trade Center as a way to spur business downtown, envisioning another large footprint development akin to his successful Rockefeller Center.

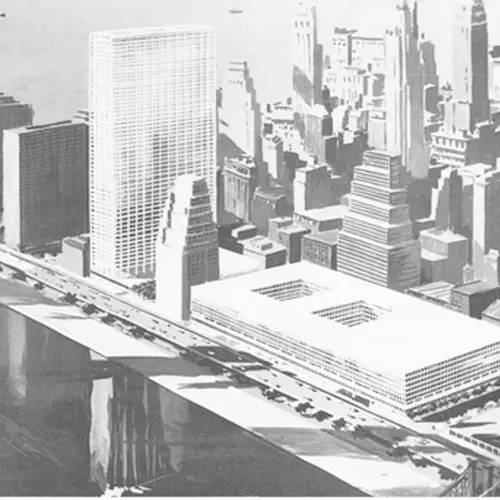

Like Rockefeller Center, the site for the present-day World Trade Center was not a shoo-in from the beginning. Rockefeller Center was initially envisioned on the East River, where the UN now stands. A 1959 rendering shows a potential World Trade Center site on the East River below Brooklyn Bridge, eradicating the Fulton Fish Market. Nearly 60 years later, Fulton Fish Market remains a contentious site fighting against redevelopment, this time against the Howard Hughes Corporation.

1959 rendering of East Side World Trade Center below Brooklyn Bridge. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

1959 rendering of East Side World Trade Center below Brooklyn Bridge. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

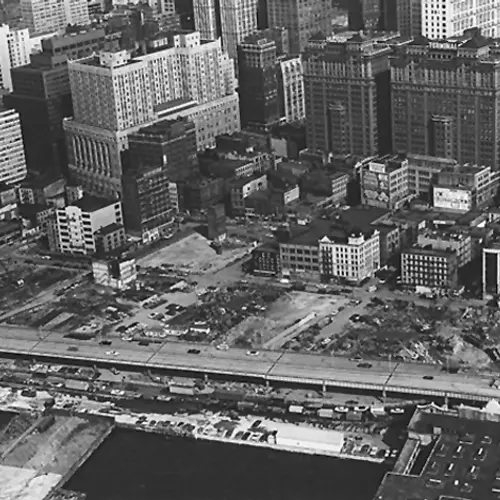

With Port Authority involvement, however, the site was moved to the Hudson Terminal Building on the West Side to accommodate New Jersey commuters. The powerful tool of urban planners, eminent domain, was used to buy out and evict the tenants of Radio Row. A lawsuit was filed in June 1962 and it eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court who declined to hear the case—a precursor to later eminent domain cases where the court would rule in favor of economic (re)development. Meanwhile, construction of the World Trade Center commenced.

The next month a newsworthy protest took place in Radio Row, with owners carrying a coffin to “symbolize the death of ‘Mr. Small Businessman.'” In addition to those in the radio industry, Radio Row had about 100 residents who also strongly resisted takeover, along with a hodgepodge of various retailers, including clothing, jewelry, stationery, gardening, hardware, and restaurants.

Part of the attachment to Radio Row came from the camaraderie of the working community there. According to writer Syd Steinhardt’s site:

“If [a customer] needed something [a merchant] didn’t carry, the merchant would go to another one to get it for his customer,” said Ronnie Nadel, a former consumer electronics wholesale executive…That way, he said, each merchant retained his customer while maintaining an incentive for his neighbor to stay in business. This culture, which might be described as competitive coexistence, was further strengthened by the segregation of specialties. The ‘brown goods’ stores stocked radios, stereos, hi-fis and televisions. The ‘white goods’ stores sold washers, dryers, dishwashers and refrigerators.

The influx of war surplus parts and the consumer product explosion turned Radio Row into a booming spot in the 1950s. As Steinhardt describes: “Its proximity to the New Jersey ferry docks and the financial district, combined with the advent of new consumer electronics goods and postwar demand, attracted floods of shoppers to the area every day except Sunday. To service their customers, stores opened at 7:00 a.m. on weekdays and closed late on Saturdays.”

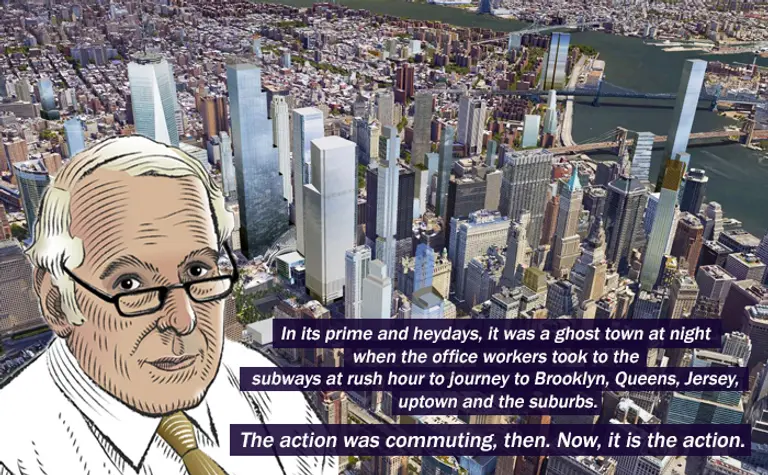

Looking back, the World Trade Center was more than a neighborhood redevelopment plan—David Rockefeller wanted to transform downtown into a global headquarters for finance and trade, much how we see it today. His interests aligned with the Port Authority who built the container ports at Newark in tandem. With a governor brother—Nelson A. Rockefeller—David’s plans were supported by the legislatures and governors of both New York and New Jersey, and there was very little that community action could accomplish.

Some of the Radio Row businesses relocated to 45th Street and other areas nearby, such as West Broadway, but many simply gave up. And slowly but surely other mono-industry neighborhoods in New York City have also faded away, such as Music Row on 48th Street. Nonetheless, the restaurant supply industry on Bowery appears to still be going strong in the face of widespread gentrification.

All this begs the question—what are the boundaries between urban redevelopment and community preservation? When a community is displaced it very often simply disperses—we also saw this in San Juan Hill, which became Lincoln Center. And in an urban center’s quest to become a world-class city, how much can be lost before its character erodes away?

RELATED:

- The history of New York’s Newspaper Row, the epicenter of 19th-century news

- Roasteries and refineries: The history of sugar and coffee in NYC

- The history of Little Syria and an immigrant community’s lasting legacy

***

Michelle Young is the founder of Untapped Cities, a publication and tour company about urban exploration and discovery in New York City. She is also an adjunct professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and is the author of a forthcoming book on the history of Broadway from Arcadia Publishing. Follow her on Twitter @untappedmich.

Get Inspired by NYC.

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

It’s a pity that the law allows expropriation for the benefit of private redevelopers. Instead, this should be restricted to things like national defense – during wartime, or urgent needs for public safety and so on. Otherwise, if somebody owns property, everyone else should just have to live with it.