Before Times Square: Celebrating New Year’s in old New York

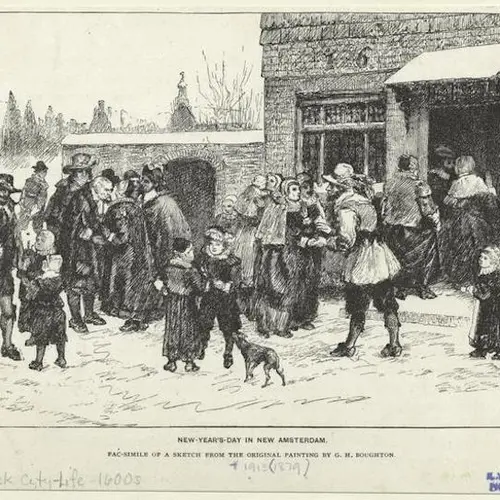

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1878). New-Year’S-Day In New Amsterdam. Courtesy of NYPL Digital Collections

Every year on December 31, the eyes of the world turn to Times Square. New Yorkers and revelers worldwide have been ringing in the New Year from 42nd Street since 1904 when Adolf Ochs christened the opening of the New York Times building on what was then Longacre Square with a New Year’s celebration complete with midnight fireworks. In 1907, Ochs began dropping a ball from the flagpole of the Times Tower, and a tradition for the ages was set in motion. But long before Ochs and his proclivity for pyrotechnics, New Yorkers had been ringing in the New Year with traditions both dignified and debauched. From the George Washington and the old Dutch custom of “Calling,” to the rancorous tooting of tin horns, one thing is clear, New York has always gone to town for the New Year.

We’ll start this story with George Washington. You may know him as a general and as a statesman, but did you know that he was also a big fan of New Year’s celebrations? Together with his friend and fellow patriot, John Pintard, who founded the New-York Historical Society, Washington liked to celebrate the New Year in New York by following the Dutch tradition of “Calling” on friends and acquaintances on New Years Day and receiving calls at his own home.

Living at 1 Cherry Street, in what was the nation’s first Presidential Mansion (later knocked down to build the Brooklyn Bridge), Washington made calls throughout Lower Manhattan.

Washington moved from New York to Philadelphia in 1790, when the Nation’s Capital moved from here to there, but his favorite New Year’s tradition stayed popular in New York. In fact, Calling remained the most popular New Year’s custom in the city throughout the first half of the 19th century. But as early as 1801, a new tradition was tolling away Downtown.

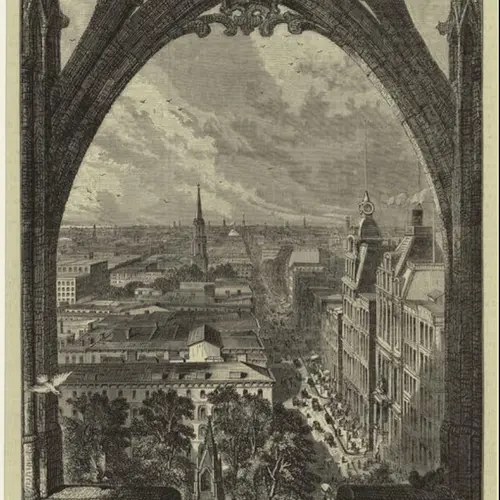

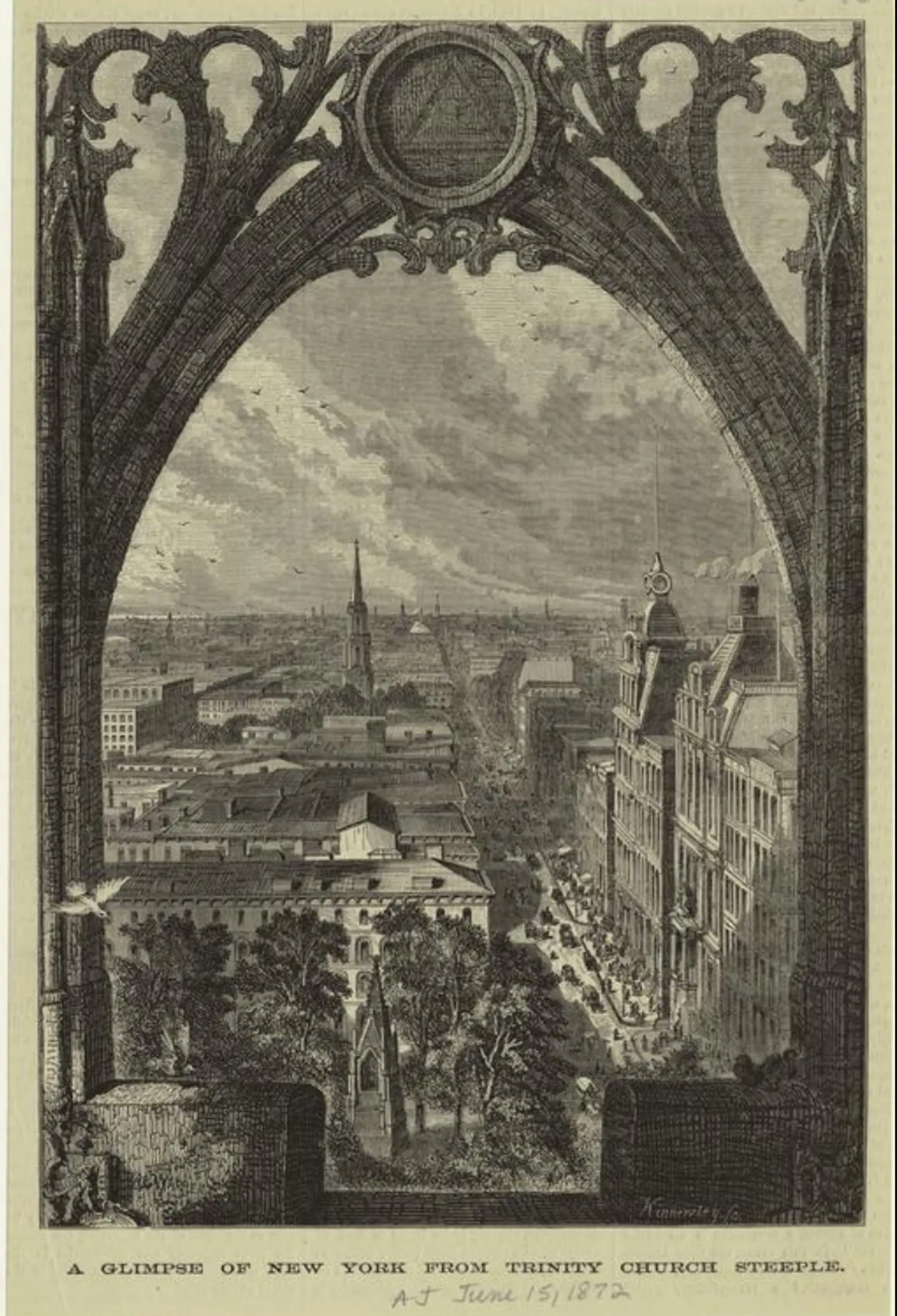

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1872-06-15). A glimpse of New York from Trinity Church steeple; Courtesy of NYPL Digital Collections

That year, the vestry minutes at Trinity Church recorded that “eight pounds be paid to the persons who rang the bells on New Years Day.” By the late 1840s, Trinity’s bells were a major part of New York’s New Year.

The second half of the 19th Century found New Yorkers quite literally ringing in the New Year at Trinity Church, because Richard Upjohn’s Trinity (the church we know today) was consecrated in 1846, and featured something the two earlier Trinity Churches did not have: a full octave of bells chiming in the belfry.

An enterprising bell ringer could toll out popular tunes from those bells, and, thankfully, Trinity’s resident ringer, James E. Ayliffe, was up to the task. The New York Herald reported that, in order to ring in 1860, Ayliffe made “the air redolent with harmony” and tolled out “Hail Columbia,” “Yankee Doodle” and “some sweet selections from ‘La Fille du Regiment.’”

By the 1870s and 1880s, Trinity’s bells drew crowds from as far as New Jersey, Long Island, and “even,” the New York Times reported, Staten Island. According to the paper, the thousands who gathered around Trinity for the New Year’s celebration represented “all classes of New York society, from the poorest to the richest.” Together, the crowd “stood quietly enjoying the glorious night and the ringing of the bells.” As the New Year dawned, they “joined their voices, and to the accompaniment of the bells, sang loudly and impressively the hymn ‘Praise God from whom all blessings flow.’”

But, by 1885, a new sound joined this heavenly chorus: the hooting of tin horns. To Reverend Dr. Morgan Dix, the rector of Trinity Church, the horns were a “horrible din” that drowned out the bells. By 1893, Dix was so aggrieved by the offending noise, he canceled the peal. (A small army of about 30 Lower East Side boys simply arrived at his home on West 25th Street equipped with horns, and proceeded to hoot their disdain).

The peal was restored the following New Year. By December 31, 1896, the New York Times reported, crowds swelled the streets of Lower Manhattan by 7 p.m. “Up and down lower Broadway the crowd wandered…and the irrepressible horn vender was in evidence at every point. As the New Year approached, the crowds became denser and denser, and there was a continuous stream of humanity parading down Broadway towards the church. At 11 o’clock, the crowds were so thick in the vicinity of the church that the cable cars, each bringing their additions to the throng, were almost entirely stalled.”

During this wall-to-wall celebration, more women took part than ever before. Women wielded more than a quarter of the tin horns that year, and, the Times noted, “to their credit, be it said, they were not lacking in ability to use them.”

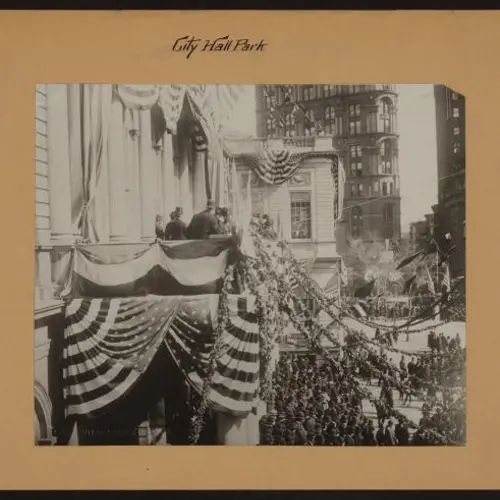

But, even a celebration like that one could not hold a candle to the festivities of December 31, 1897, for New Yorkers weren’t just ringing in a New Year, they were inaugurating a whole new city. January 1st, 1898, marked the consolidation of all five boroughs of New York City into a brand new municipality: Greater New York.

And where better to celebrate the dawn of the great new city than City Hall? A hard, driving rain poured over New York that night, but the city turned out just as hard. To mark the New Year and the new city, fireworks blasted overhead, cannon fire thundered from the Battery, steamboats whistled in the harbor, skyrockets showered City Hall in a blaze of red, blue, silver and gold, and brass bands played for a crowd of 50,000.

Suddenly, on the stroke of midnight, a new flag was electrically unfurled over City Hall, and the City of New York was born.

With a new city came a new tradition. As Greater New York blossomed into the greatest city of the 20th Century, Midtown Manhattan became “The Crossroads of the World,” and Times Square began serving up a world-class New Year’s celebration. These days, more than a billion people worldwide watch the ceremony in Times Square, and who knows, some of them might even be tooting tin horns.

+++

Editor’s note: A version of this post was originally published on December 19, 2018.

RELATED:

- VIDEO: Travel back to 1904 for the first New Year’s Eve in Times Square

- New Year’s Eve in numbers: Fun facts about the Times Square ball drop

- The history of the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree, a NYC holiday tradition

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.