From George Washington to war bonds: The revolutionary history of Fraunces Tavern

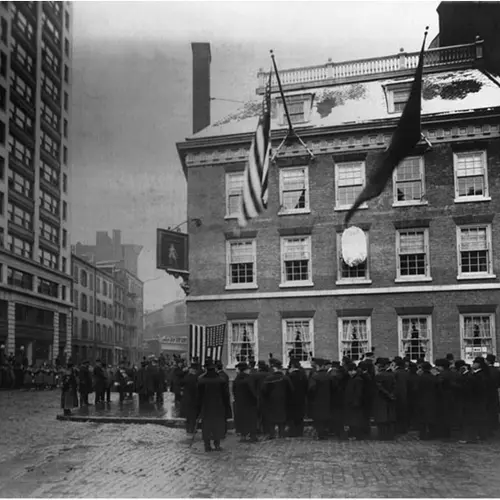

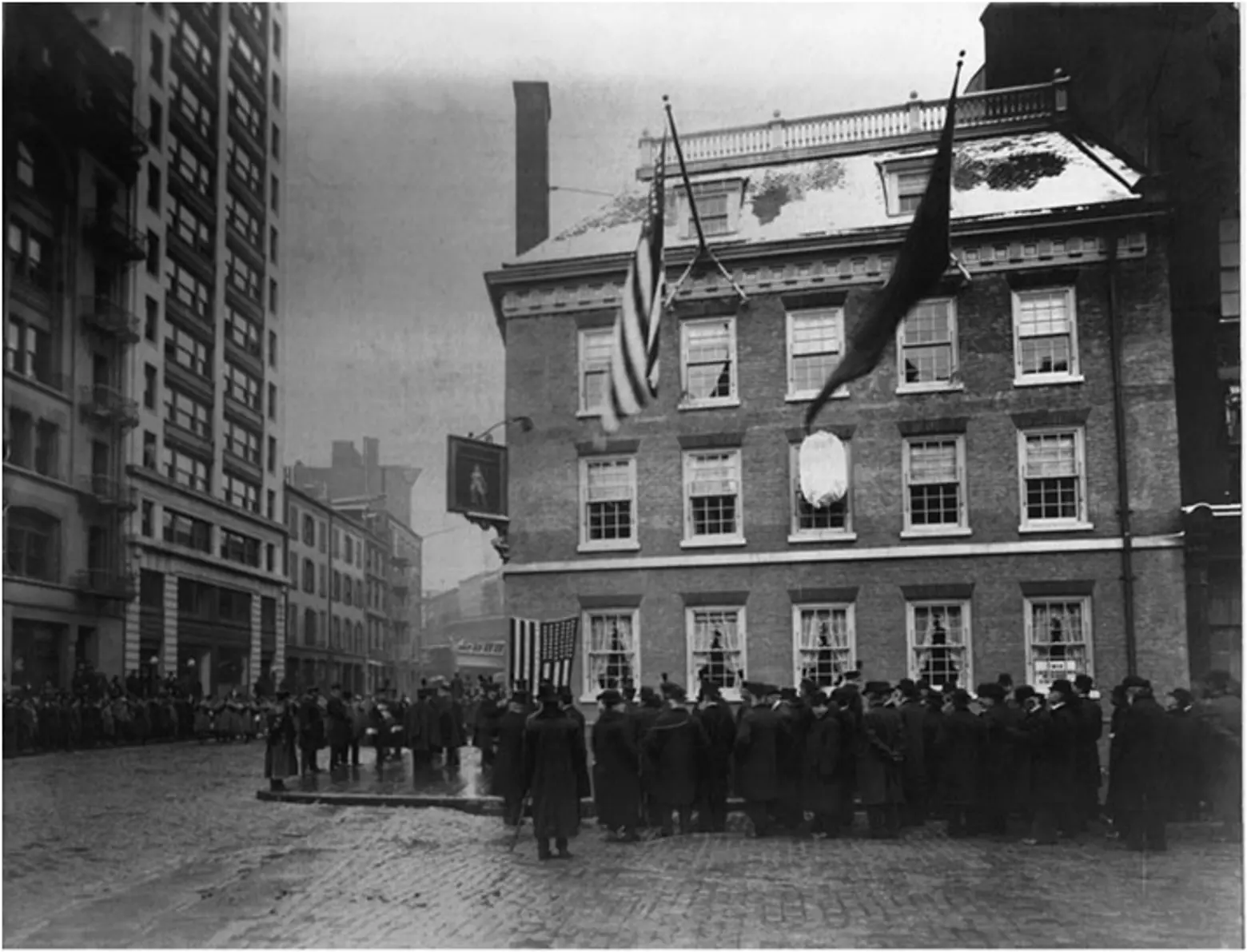

Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York outside 54 Pearl Street on opening day. Taken from Broad Street facing east. 1907. From the archives at Fraunces Tavern Museum. Courtesy of the Fraunces Tavern Museum

Fraunces Tavern is breaking out the champagne this year to celebrate its 300th birthday. Called “the oldest standing structure in Manhattan,” the building you see today at the corner of Broad and Pearl Streets owes much to 20th-century reconstruction and restoration, but the site has a storied and stately past. In fact, any toasts delivered to mark the Tavern’s tri-centennial will have to stack up against George Washington’s farewell toast to his officers, delivered in the Tavern’s Long Room, on December 4, 1783.

Named for Samuel Fraunces, the patriot, spy, steward, and gourmand, who turned the old De Lancey Mansion at 54 Pearl Street into 18th century New York’s hottest watering hole, Fraunces Tavern connects New York’s proud immigrant history with its Dutch past, Revolutionary glory, maritime heritage, and continuous culinary prowess. Dive into the building’s unparalleled past and discover secrets and statesmen, murder and merriment – all served up alongside oysters as big as your face.

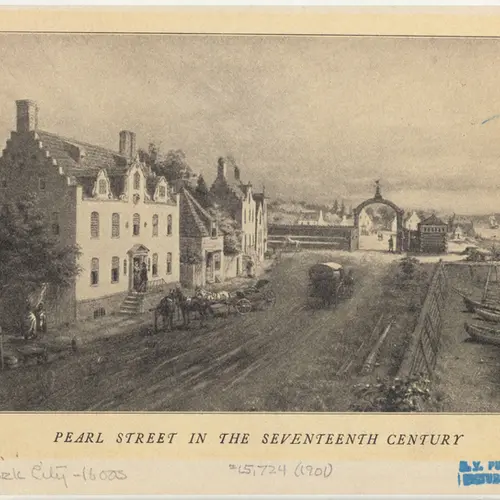

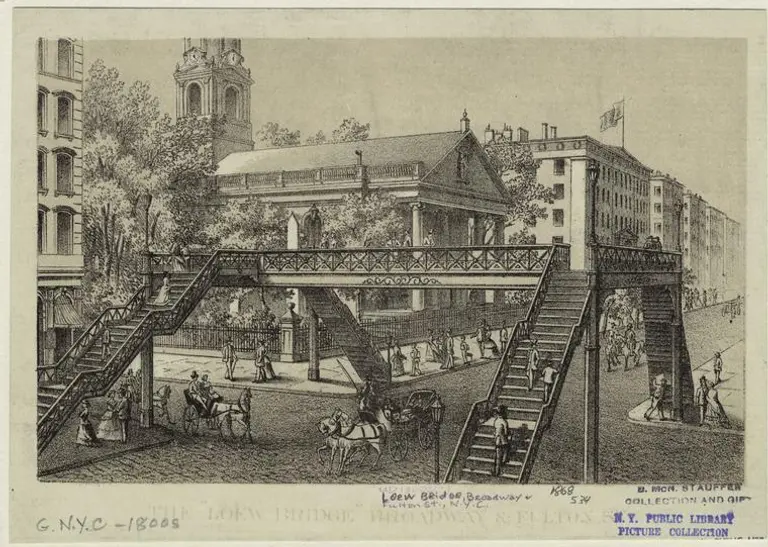

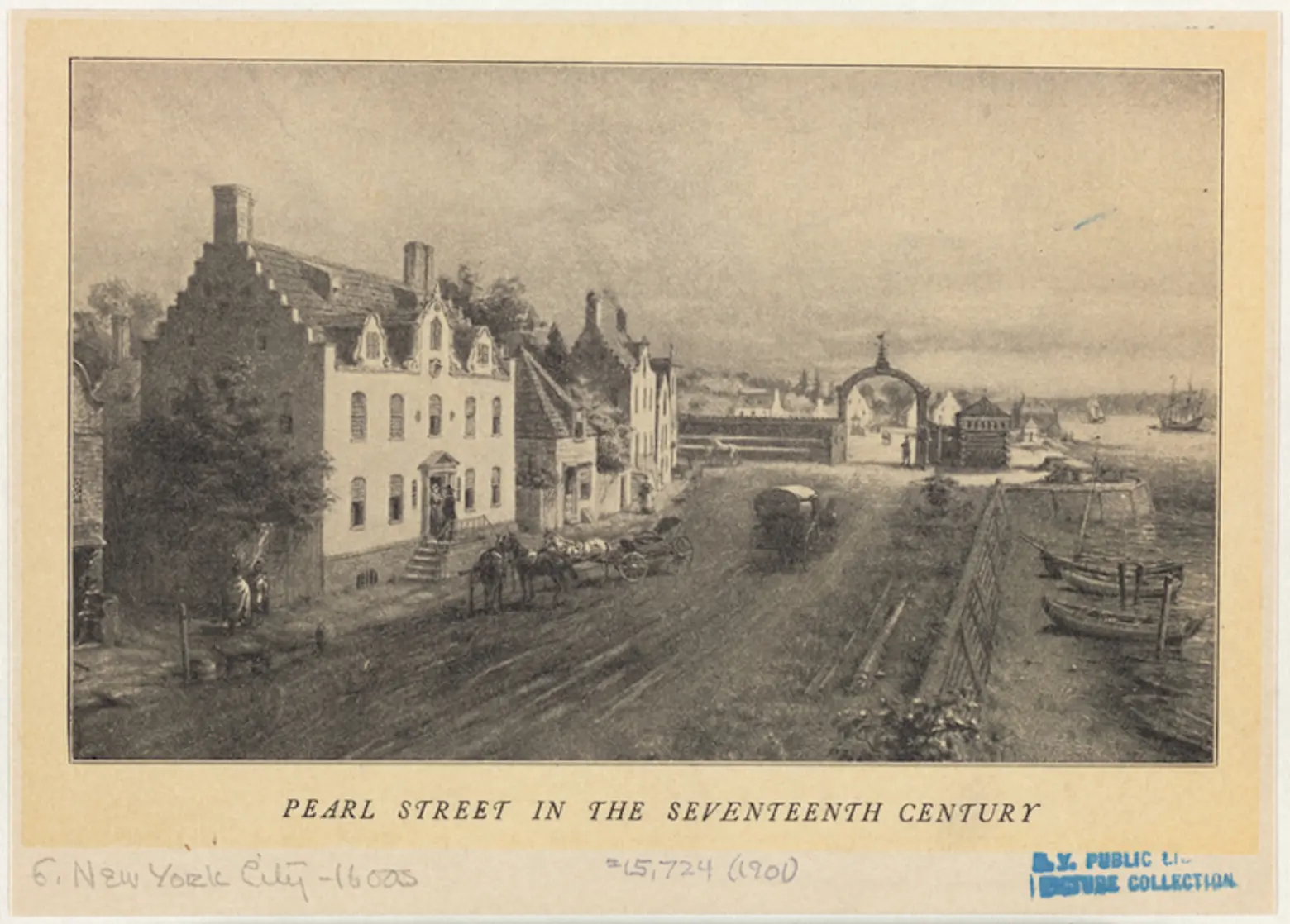

“Pearl Street in the 17th Century,” 1901 via NYPL Digital Collections

Today, Fraunces Tavern backs up to Water Street, but the location actually began its life underwater. The block that currently includes 54 Pearl Street was submerged until 1689 when new landfill made the area the first extension of the Manhattan shoreline for commercial purposes.

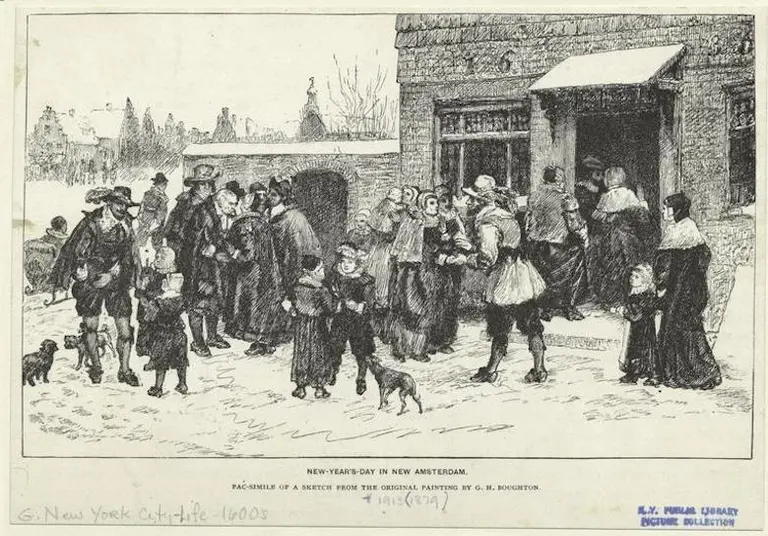

The newly created lot on Pearl Street originally belonged to Stephanus Van Cortlandt, whose father, Oloff, had arrived in New Amsterdam in 1638 as a soldier of the Dutch West India Company, and eventually became treasurer and mayor of the city. Stephanus himself was born in New Amsterdam and became the first native New Yorker to serve as mayor, a post he held in 1677, and again from 1686 to 1687 when the Fraunces Tavern block was being created.

In 1700, Stephanus’s daughter, Ann, married Etienne De Lancey, who purchased the lot at 54 Pearl that same year. In 1719, De Lancey began planning “a large brick house,” for the property. While the structure that is now Fraunces’ Tavern was first known as the De Lancey Mansion, it is not known if the family ever lived in the house, or if they used it as a rental property.

By the late 1730s, the mansion served as the domain of dance master Henry Holt, who rented the space and hosted dance classes and balls at the address. Through the 1740s and 50s, De Lancey’s son Oliver and his business associates used the site as headquarters for an imports firm, specializing in items from Europe and the East and West Indies. That enterprise went south, and De Lancey, Robinson and Co. sold 54 Pearl Street to Samuel Fraunces in 1762.

The historical record finds Fraunces on the scene in New York City in 1755. That year, he registered with the city a “freeman” and “innholder.” Fraunces’ inn holdings included The Free Mason’s Arms, on Broadway, and later, Vauxhall Gardens, at the Battery. Fraunces mortgaged The Free Mason’s Arms in 1762 to buy 54 Pearl Street. There, he opened the Sign of Queen Charlotte, popularly known as The Queen’s Head Tavern.

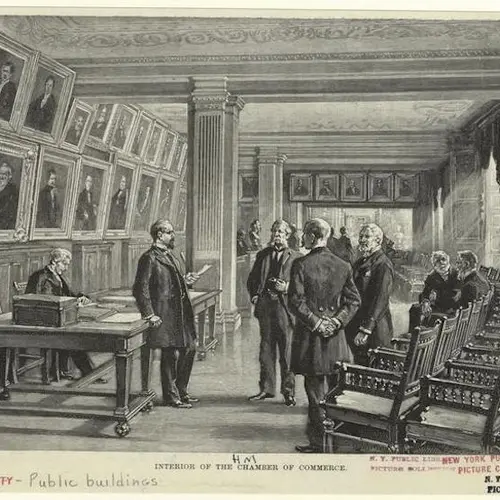

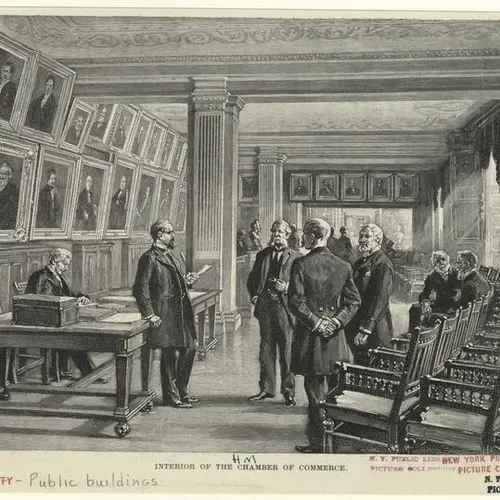

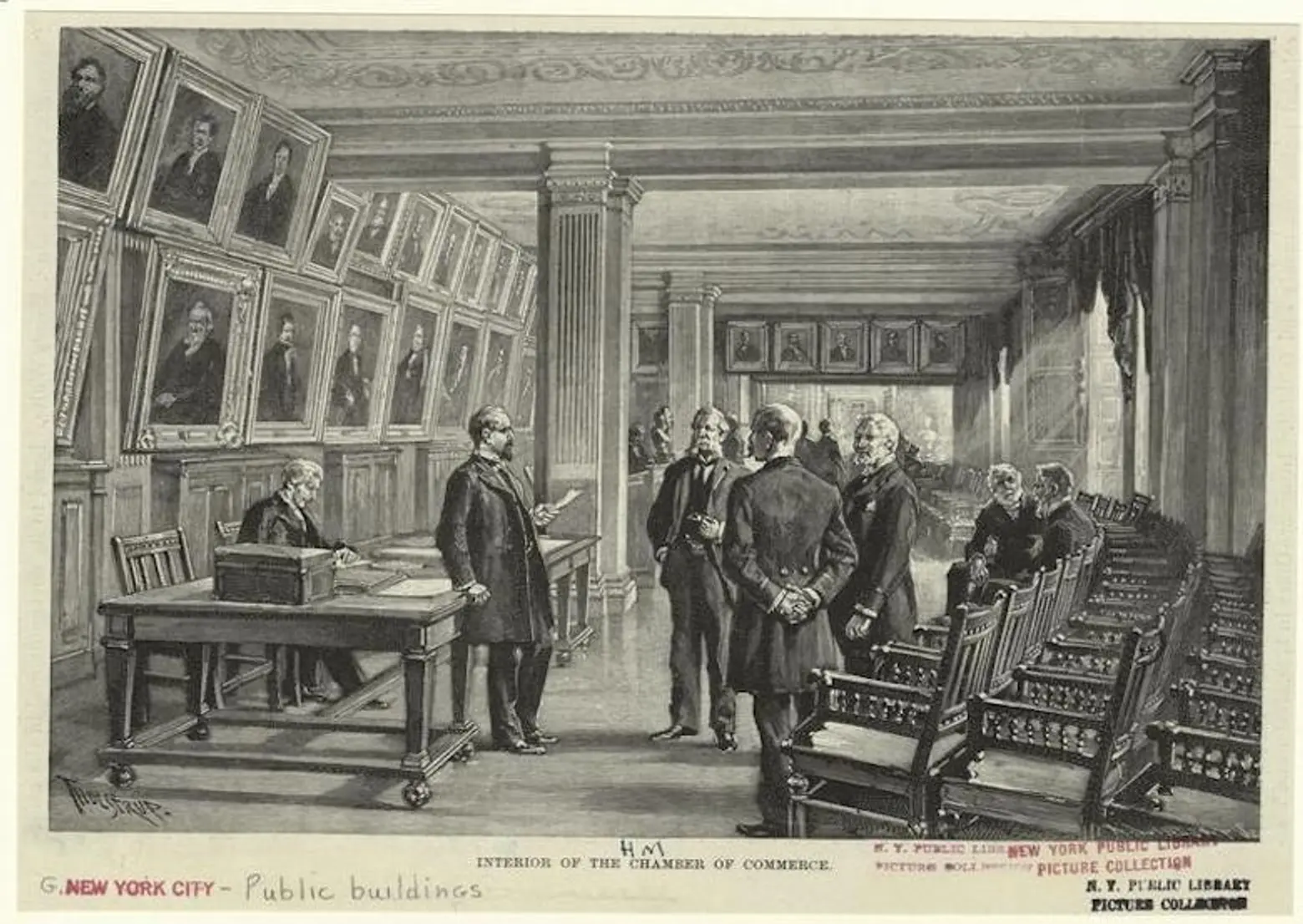

Interior of the Chamber of Commerce, 1850 via NYPL Digital Collections

The Queen’s Head thrived amongst the wharves and slips on the city’s waterfront. The Tavern bustled with the merchants, traders, travelers, and locals who exchanged goods and gossip across Fraunces’ table. The scene was so conducive to trade that the New York Chamber of Commerce was founded at the Tavern in 1768.

Long a favorite haunt of the New York chapter of the Sons of Liberty, who planned their New York Tea Party there in 1774, Fraunces Tavern was thrust into the Revolution in a blaze of cannon fire, on August 23, 1775. That night, an exchange of fire between America militiamen and the British Battleship HMS Asia, stationed in New York Harbor, sent an 18-pound British cannonball sailing through the Tavern’s roof.

The following year, the Provincial Congress of New York held meetings at the Tavern. George Washington attended, for he had arrived in New York City as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army in April of 1776.

Fraunces’ own war record was an illustrious one. In 1778, he was captured in New Jersey, taken back to New York, and installed in his tavern as a prisoner of war, tasked with cooking for the British general James Robertson. While at his post, Fraunces snuck food, clothing, and money to American prisoners of war held in New York City, and he took advantage of the convivial atmosphere amongst the British generals in his dining room: with a keen ear, Fraunces listened in, and working as a spy for Washington, sent clandestine information to the general.

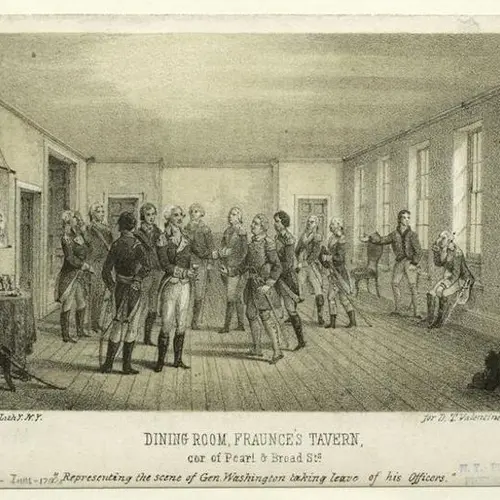

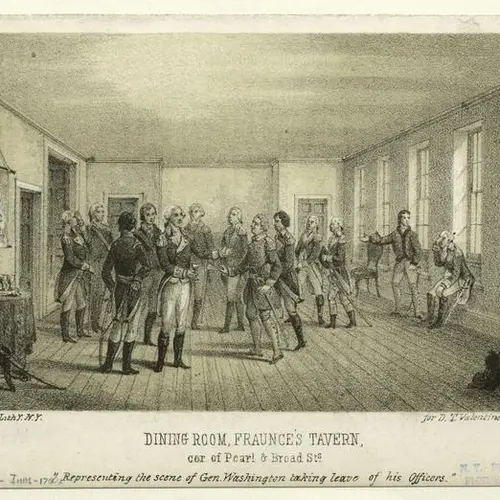

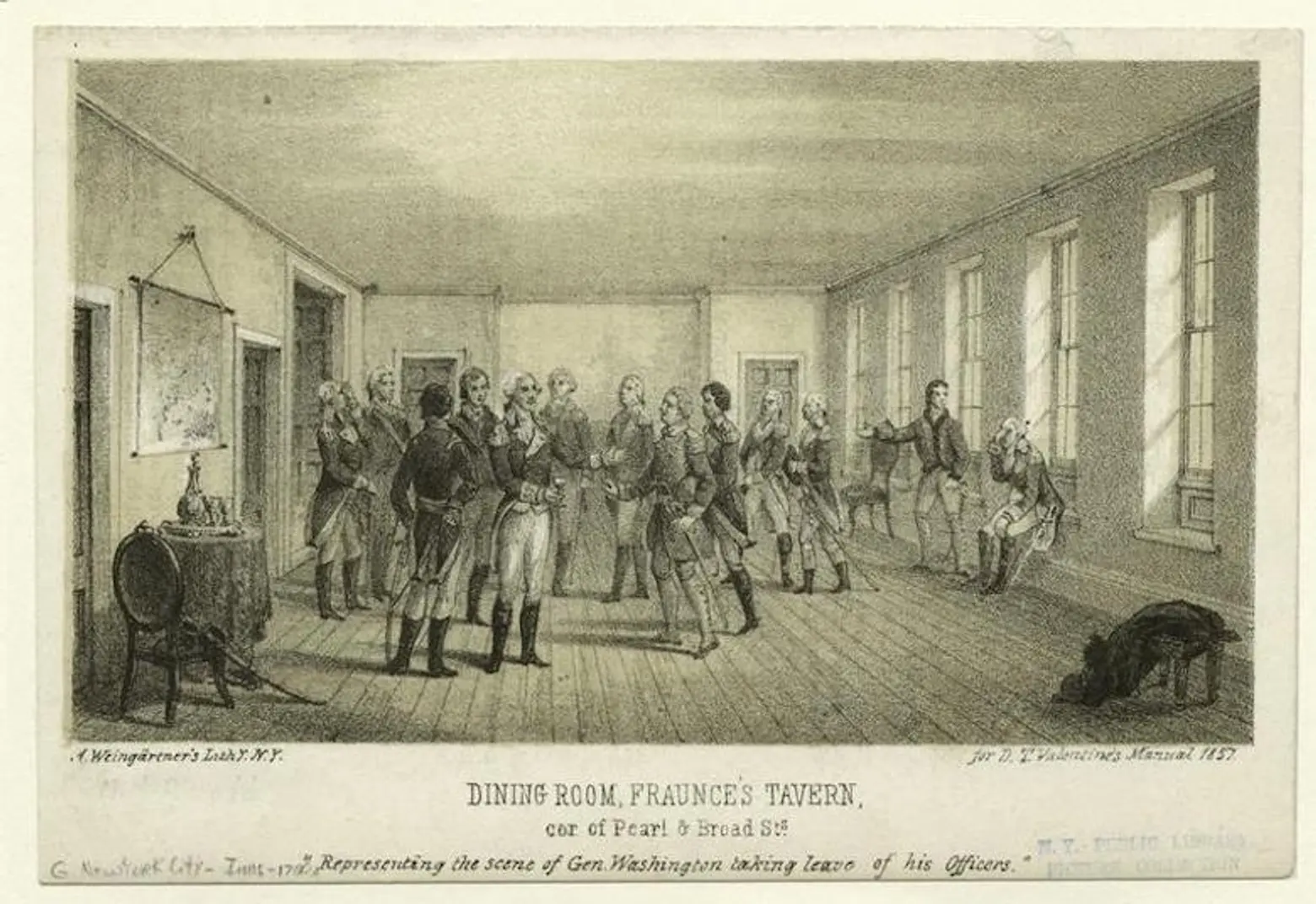

“Representing the scene of Gen. Washington taking leave of his Officers,” 1857 via NYPL Digital Collections

Washington wrote that during his wartime service Fraunces “maintained a constant Friendship and attention to the Cause of our Country and its Independence and Freedom…”

The Tavern’s role in the “independence and freedom” of the nation and its citizens did not end when the War was over. Enslaved people throughout the 13 colonies who fought with the British Army had been promised freedom in exchange for their service at the War’s end. As the British prepared to evacuate New York City, General Birch issued certificates of freedom at Fraunces Tavern to black loyalists who had served the crown.

On Evacuation Day itself, November 25, 1783, New York Governor George Clinton held the state’s official celebration at Fraunces Tavern, and of course, nine days later, Washington bid his famous farewell to his Officers, and departed from Fraunces Tavern to meet the Continental Congress at Annapolis, and resign his post as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army.

When New York City emerged as the nation’s first capital, Fraunces Tavern followed suit, as the epicenter of national affairs. Samuel Fraunces became George Washington’s personal steward, and the Continental Congress leased the Tavern as office space: The first Departments of War, Finance and Foreign Affairs were headquartered in the building. Those three agencies functioned in the Tavern until 1788, under the direction of men like John Jay and Henry Knox. John Jay would be back soon, for, in 1790, the original justices of the Supreme Court met for a celebratory meal at Fraunces Tavern to celebrate the Court’s opening.

Fraunces sold the tavern in 1785, and it changed hands a few times over the next decade, until, by 1795, it was being run as a boarding house by one Mrs. Orcet. The Tavern would be run under a variety of managers as a boarding house, with a bar on the first floor, for much of the 19th century, but revolutionaries continued to gather at their favorite place. In fact, on July 4, 1804, just a week before their infamous duel, both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr attended a meeting for veterans of the Revolution at Fraunces Tavern.

Fraunces Tavern from Pearl Street, looking north. Circa 1880-1906. From the archives at Fraunces Tavern Museum. Courtesy of the Fraunces Tavern Museum.

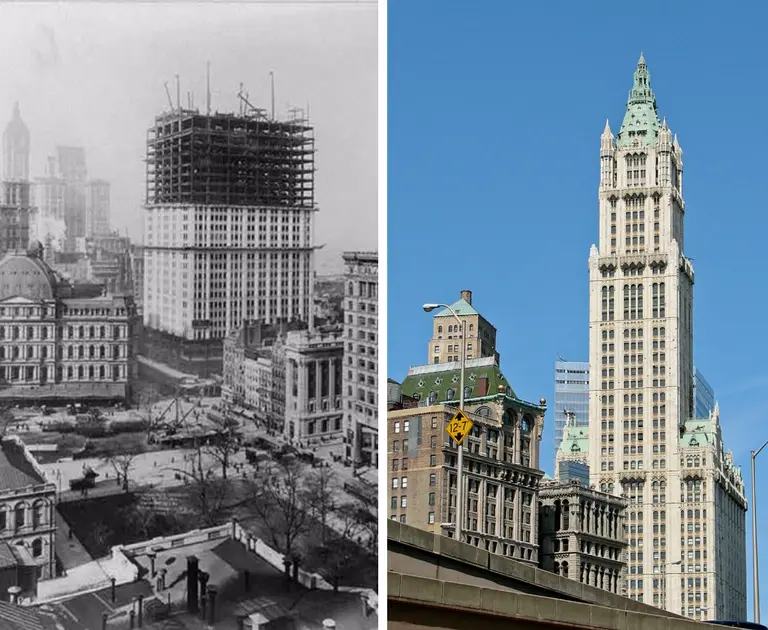

By 1883, veterans of the Revolution had passed away. But, their progeny remembered 54 Pearl Street, and founded the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York in the Tavern on the centennial of Washington’s farewell speech. By that time, so many changes had been made to the building that it was rendered nearly unrecognizable. In fact, by century’s end, Fraunces Tavern had two new floors, a flat roof, a cast iron exterior, and glass storefronts. In 1890, the original timbers were sold as souvenirs.

Restoration of Fraunces Tavern. Taken from Pearl Street, facing south. 1906. From the archive at Fraunces Tavern Museum. Courtesy of Fraunces Tavern Museum.

Restoration of Fraunces Tavern. Taken from Pearl Street, facing south. 1906. From the archive at Fraunces Tavern Museum. Courtesy of Fraunces Tavern Museum.

As the city grew up and around Fraunces Tavern, the building was threatened with demolition. In 1900, the Daughters of the American Revolution mounted a campaign to save the structure. The City itself stepped in, in 1903, and acquired Fraunces Tavern by eminent domain, designating the property as a park. The Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York (SRNY) bought the building the following year, and the city withdrew the park designation. The SRNY began restoring and reconstructing the building as a restaurant and museum, which opened December 4, 1907.

The restoration revealed the Tavern’s original red and yellow brick, as well as its original roofline, but architect William H. Mersereau could not find an image of the Tavern prior to the 1832 fire that had severely damaged the building, so his reconstruction is not based on the Tavern’s original design, but on the principals of Colonial Revival architecture, and an educated estimation of what the Tavern may have looked like when Fraunces himself was running the kitchen.

Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York sell war bonds outside Fraunces Tavern in 1918. The archives at Fraunces Tavern Museum. Courtesy of Fraunces Tavern Museum.

In the 20th century, the Tavern honored its patriotic roots and war bonds were sold in the Long Room when the United States entered the First World War in 1917. Following the Second World War, the SRNY purchased four additional buildings on Pearl, Broad and Water streets, and incorporated them into the museum complex.

By the 1960s, New York City had embarked on its own preservation movement, and the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) was born in 1965. That year, the LPC designated Fraunces Tavern a New York City Landmark, and the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008. The Museum has been open seven days a week since 2011.

Fraunces Tavern today, via Flickr cc

This year marks the Tavern’s 300th birthday. To honor the occasion, the museum has undertaken the Long Room Enhancement Project, equipping the historic space with a new reader rail, updated labels, and interactive components that bring the sounds and smells of an 18th-century tavern to life. Additionally, the Tavern has made its fascinating photo collection available online, and the Museum is planning an anniversary exhibition focusing on the history, construction and restoration of the building. The exhibit will open this summer during an official 300th birthday celebration, complete with cake and a champagne toast.

Find out more about the festivities here.

RELATED: