The wild and dark history of the Empire State Building

Known for its record-breaking height and sophisticated Art Deco style, the Empire State Building is one of New York City’s, if not the world’s, most recognized landmarks. While the building is often used in popular culture as light-natured fodder—such as the opening backdrop to your favorite cookie-cutter rom-com or the romantic meeting spot for star-crossed lovers—the building’s past is far more ominous than many of us realize. From failed suicide attempts to accidental plane crashes, its history casts a vibrant lineup of plot-lines and characters spanning the past 90 years.

Design and Construction

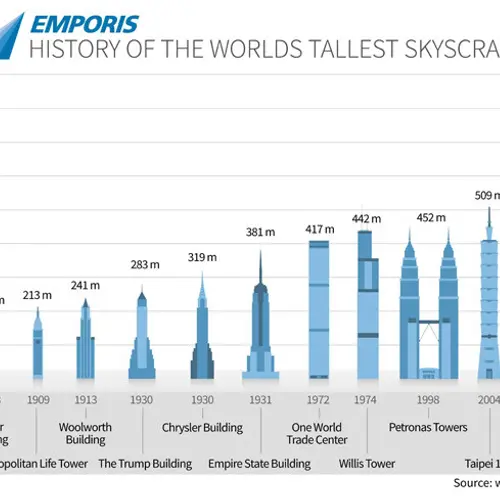

The Eiffel Tower, measuring 984 feet, was built in Paris in 1889. And as many French things do, it taunted American architects with its lofty height. The French feat challenged Americans to build something even taller, and its completion marked the beginning of the 20th century’s great skyscraper race.

Prior to the Empire State Building, the U.S. lineup of tall towers included the Metropolitan Life Tower at 700 feet, constructed in 1909, followed by the 729-foot Woolworth Building in 1913, and finally the 927-foot Bank of Manhattan Building in 1929.

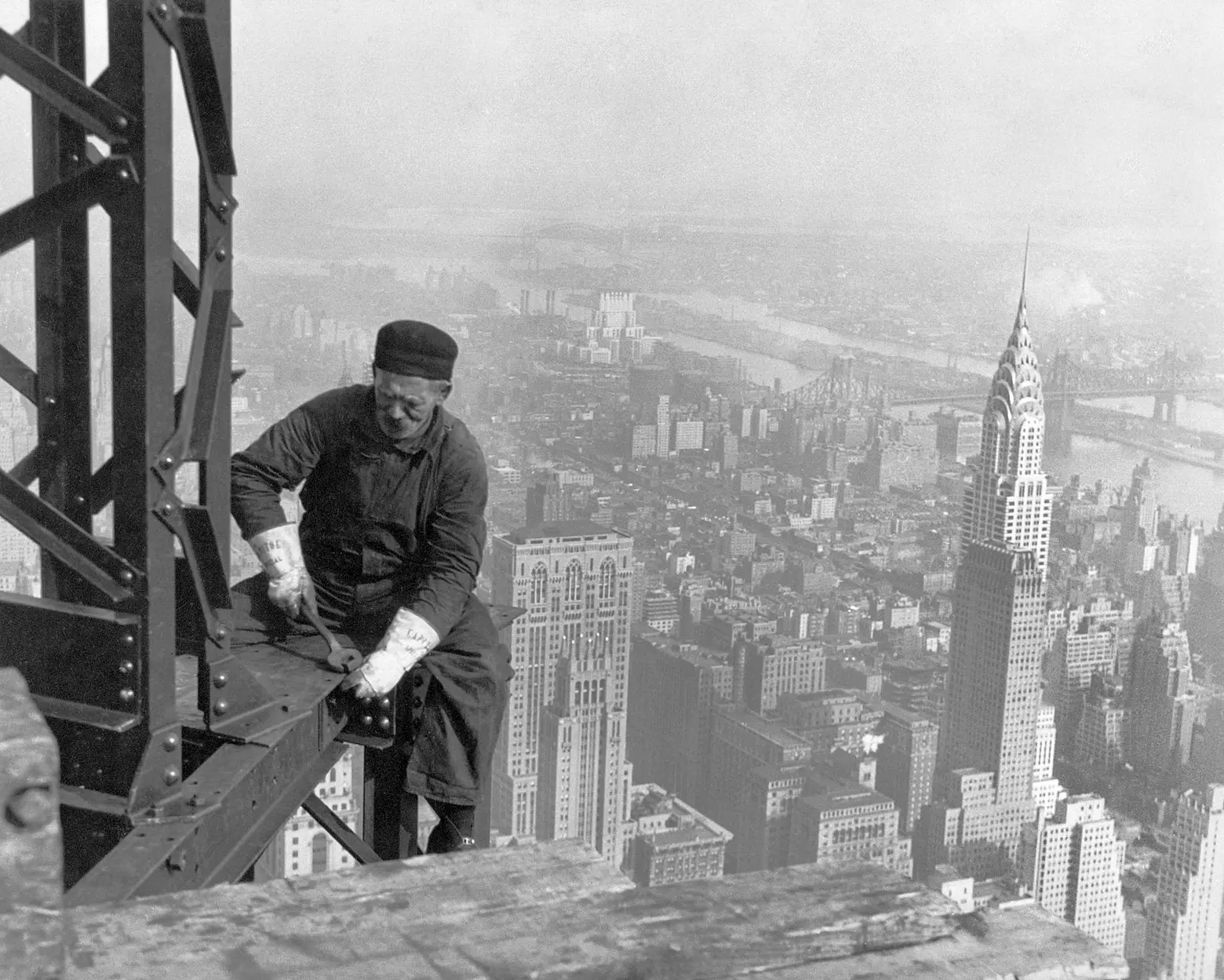

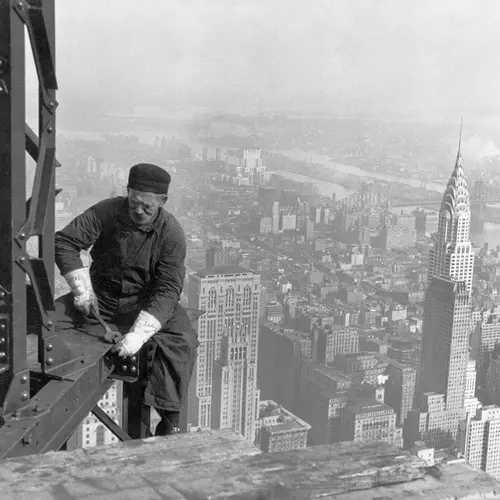

Photograph of a Workman on the Framework of the Empire State Building by Lewis Hine. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Photograph of a Workman on the Framework of the Empire State Building by Lewis Hine. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Jakob Raskob, the former vice president of General Motors, decided to make his mark in the race by pitting himself against the founder of the Chrysler Corporation, Walter Chrysler. With Chrysler keeping these plans for a new tower tightly under wraps, Raskob had to account for the unknown.

Raskob and his partners purchased the 34th street parcel of property in 1929 for $16 million and quickly hired architect William F. Lamb, of the firm Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, who completed their original drawings for the Empire State Building in just two weeks. The logic of Lamb’s plans was simple: He organized the space in the center of the building as compactly as possible containing vertical circulation, toilets, mail chutes, shafts and corridors, and as the height of the building increased, the size of the floors and number of elevators decreased.

Whether or not it was enough to out-scale Chrysler remained unknown, but with the competition heating up, Mr. Raskob found his own solution to the problem. When examining a scale model of the building the tycoon exclaimed, “It needs a hat!” New plans were drawn and the proposed building stretched to a whopping 1,250 feet thanks to a crafty spire.

The building was constructed between 1929 and 1931, and cost $40,948,900 to erect. Upon completion, it easily surpassed its competitors, raising the New York skyline to the highest of heights. In addition to its impressive stature, the speed of construction was also unprecedented. The builders innovated in ways that saved time, money, and manpower. For example, a railway system was set up on-site with cars that could hold up to eight times more than a wheelbarrow, making it easy to move materials more efficiently. In total the building was finished in just 410 days, almost three months ahead of schedule.

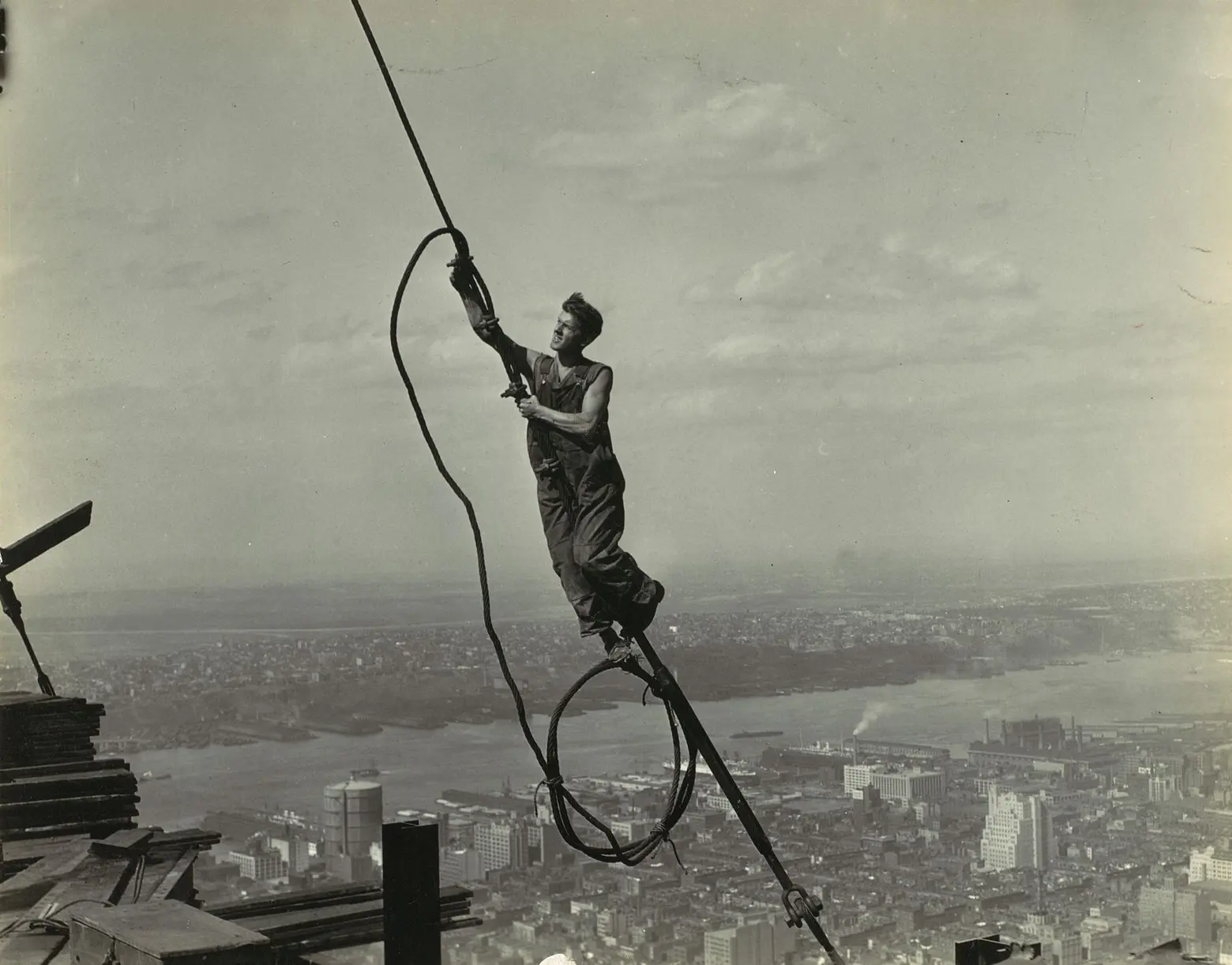

Icarus, Empire State Building. Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Open Access.

Icarus, Empire State Building. Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Open Access.

Photographer Lewis Hine was commissioned to document the process. To gain the vantage points he needed to capture the work being done at such extreme heights, Hine photographed workers from a specially designed basket that swung out 1,000 feet above Fifth Avenue. Although Hine was only hired to photograph the building of this great monument, his work also focused heavily on the men who created it. The artist referred to these images as “work portraits” and they were a nod to his desire to capture character rather than just architecture.

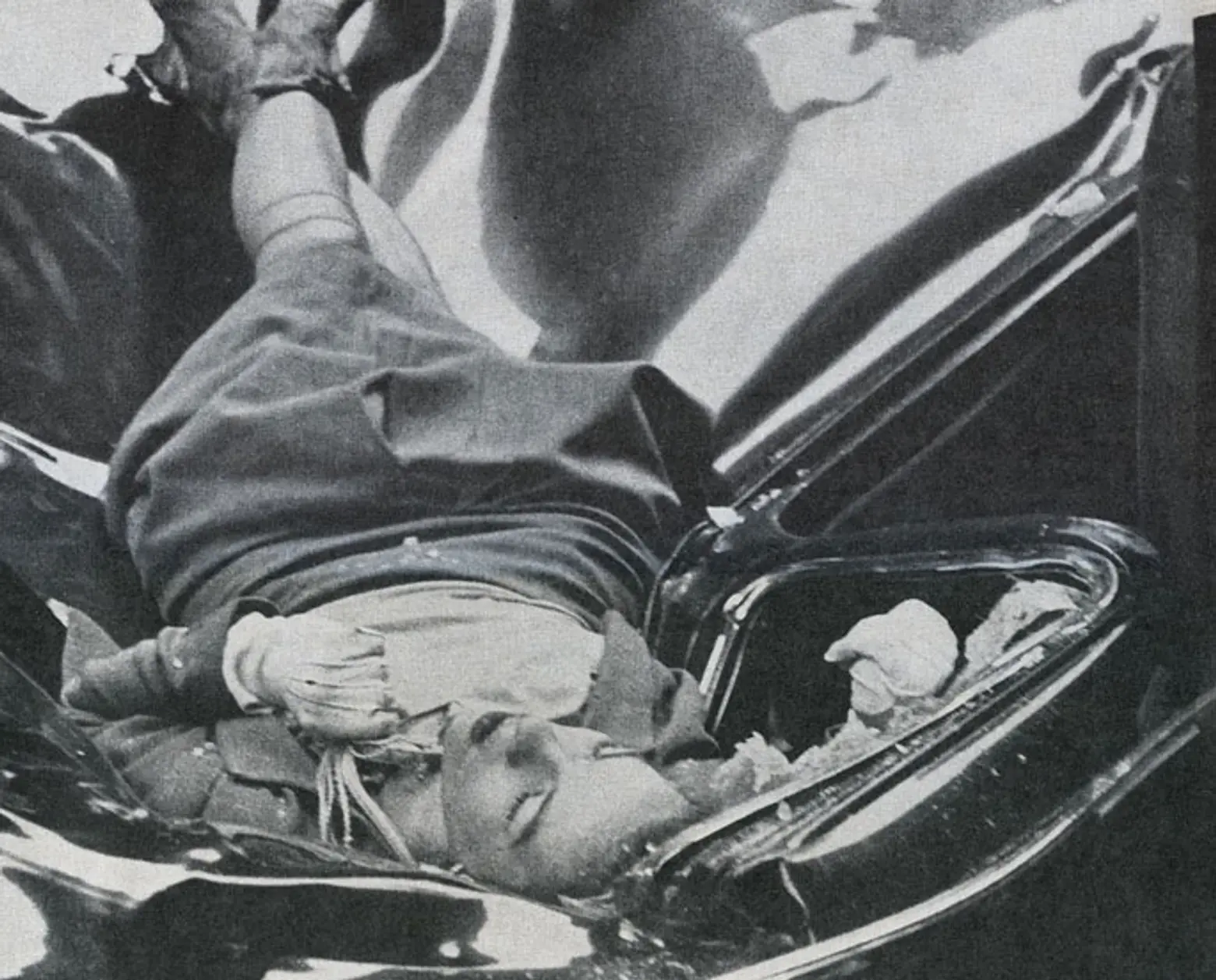

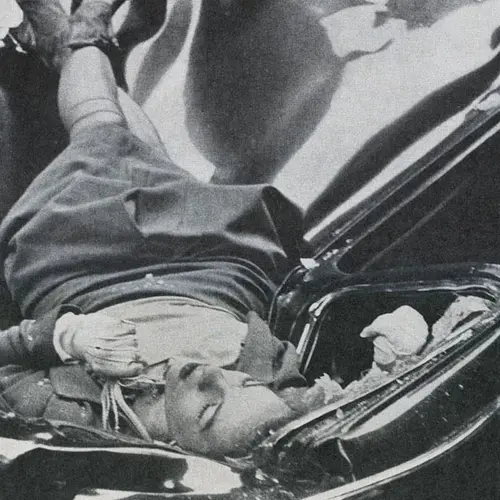

“The Most Beautiful Suicide” by Robert C. Wiles from the May 12, 1947 issue of Life Magazine; Via Wikimedia

“The Most Beautiful Suicide” by Robert C. Wiles from the May 12, 1947 issue of Life Magazine; Via Wikimedia

Suicides

There have been more than 30 suicide attempts at the Empire State Building. The first occurred while the building was still under construction when a worker who was laid off threw himself down an open elevator shaft. However, one of the most famous incidents took place on May 1, 1947, when 23-year-old Evelyn McHale leaped to her death from the 86th-floor observation deck. The beautiful young woman was wearing pearls and white gloves and landed on the roof of a United Nations limousine parked outside of the building. With legs elegantly crossing at the ankles, her body lay morbidly lifeless but majestically intact as the car’s metal folded around her like sheets framing her head and arms. Present on the scene was photography student Robert Wiles who took a photo of McHale just a few minutes after her death. This photo later ran in the May 12, 1947, edition of Life magazine. Her death was given the title as “the most beautiful suicide,” and the imagery was used by visual artist Andy Warhol in his print series, Suicide (Fallen Body).

On account of unanticipated conditions and poor planning, there have been two cases where jumpers survived by failing to fall more than one floor. The first was Elvita Adams who on December 2, 1972, jumped from the 86th floor only to be interrupted by a gust of wind that blew her body back onto the 85th floor, leaving her alive with a mere broken hip. The second was on April 25, 2013, when 33-year old Nathanial Simone jumped from the 86th-floor observation deck, fortunately, landing shortly after on an 85th-floor ledge.

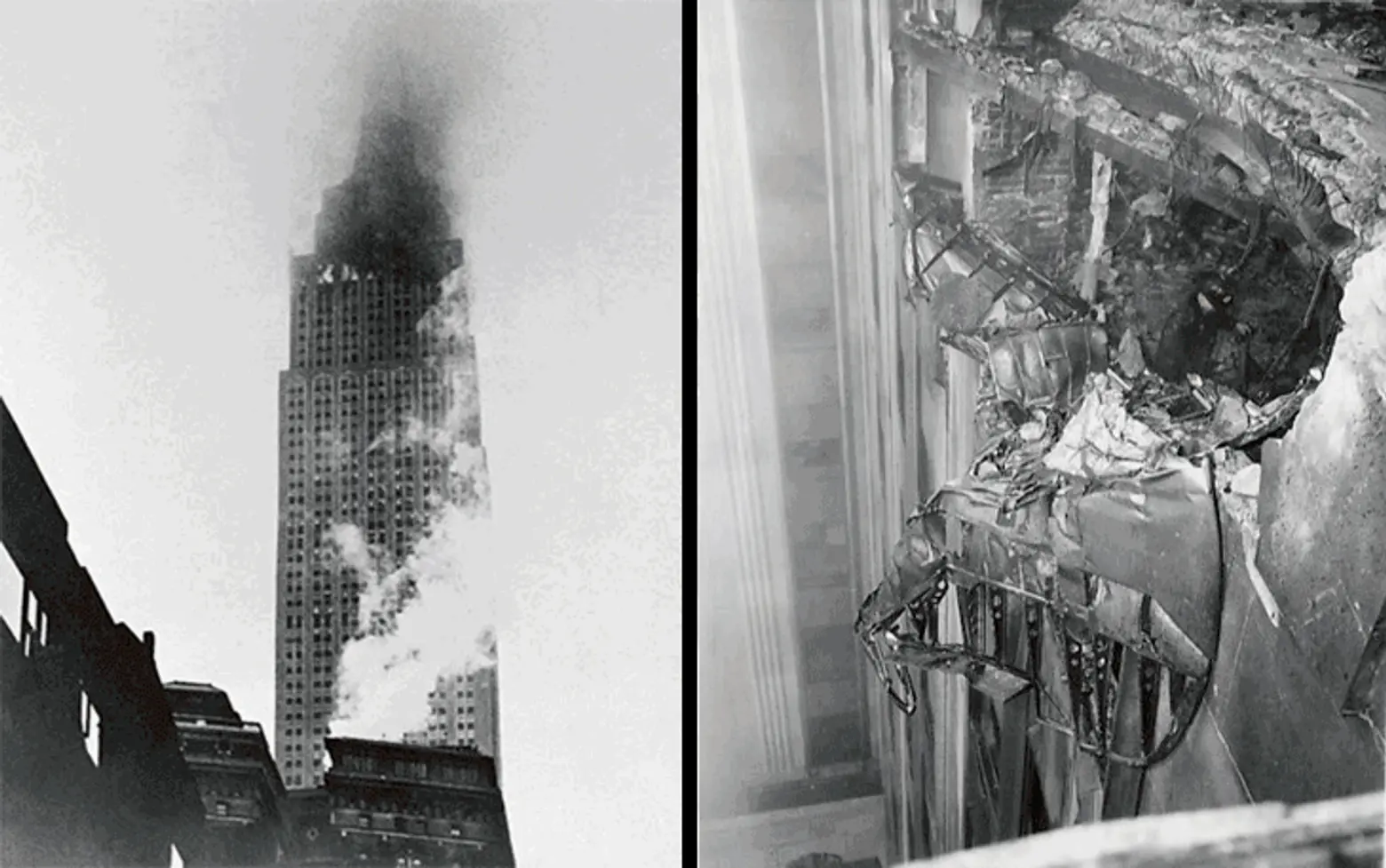

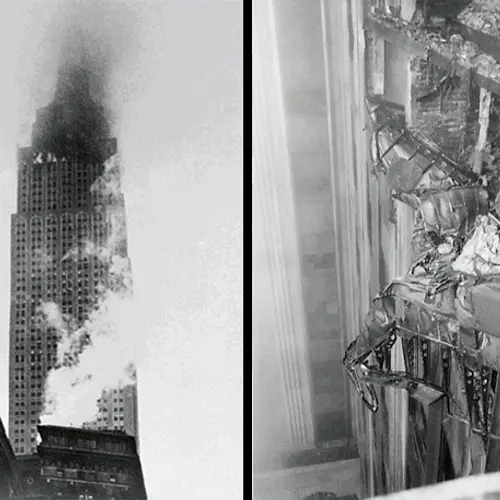

Photo of a B-25 bomber that crashed into the Empire States Building on the 78th floor in 1945. Photo via Wiki Commons

Photo of a B-25 bomber that crashed into the Empire States Building on the 78th floor in 1945. Photo via Wiki Commons

Unexpected Tragedies

In addition to suicide, the Empire State Building’s death toll also includes tragedies resulting from two shootings, as well as a plane crash. On February 23, 1997, Ali Hassan Abu Kamal, a 69-year-old Palestinian teacher, opened fire on the observation deck killing one man and injuring six others before shooting himself in the head.

The second shooting took place on August 24, 2012, when Jeffrey Johnson, a clothing designer who had been laid off, shot and killed a former co-worker outside of the building. The gunman, who was hiding behind a van, emerged onto 33rd street first shooting his target from afar. After his victim fell to the ground, Johnson approached the body and fired several more rounds while standing over him. Johnson was later shot down by police officers stationed in front of the Empire State Building’s 5th Avenue entrance. The officers fired a total of 16 rounds, killing Johnson and injuring nine bystanders, none of whom, miraculously, suffered life-threatening wounds.

On July 28, 1945, Lt. Colonel William Smith crashed a U.S. Army B-25 bomber into the north side of the Empire State Building’s 79th floor. The city was cloaked in a dense fog on the morning of the crash, and the Lt. Colonel, who was on his way to Newark to pick up his commanding officer, somehow ended up over LaGuardia asking for a weather report. Although he was encouraged to land, Smith still requested military permission to continue to Newark. The last transmission from the LaGuardia tower to the plane was a foreboding warning: “From where I’m sitting, I can’t see the top of the Empire State Building.”

Photo of workmen clearing the wreckage of the B-25 bomber that crashed into the Empire States Building at the 78th floor in 1945, via Wiki Commons

Photo of workmen clearing the wreckage of the B-25 bomber that crashed into the Empire States Building at the 78th floor in 1945, via Wiki Commons

In an attempt to regain visibility, Smith lowered the bomber only to find himself amid the towering skyscrapers of midtown Manhattan. Initially, he was headed straight for the New York Central Building but was able to shift west avoiding contact. He continued to swerve around several other buildings until his luck ran out and he found himself headed straight for the Empire State Building.

The pilot tried to climb and twist away but it was too late. Upon impact, the bomber made a hole in the building measuring eighteen feet high and twenty feet wide, and the plane’s high-octane fuel exploded, shooting flames throughout the building that reached down to the 75th floor. 13 people died.

If those walls could talk; the Empire State Building’s precarious past is almost as haunting and dualistic as New York itself.

RELATED:

- From oysters to falafel: The complete history of street vending in NYC

- The Urban Lens: Documenting the change in Tribeca from the early 1900s to present day

- The history behind 42nd Street’s lost Airlines Terminal Building

Editor’s note 2/18/2021: The original version of this post was published on August 29, 2017.

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Empire State took on a B52 bomber and stood strong, and both Trade Center buildings come down from commercial jets? We should open our eyes and see the truth!

A B25 two engine, a much smaller plane.