The hopping history of German breweries in Yorkville

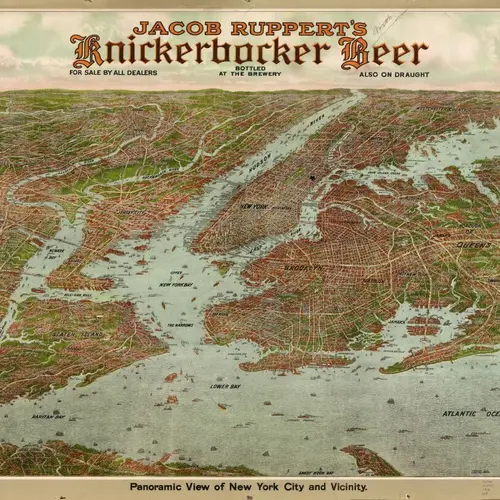

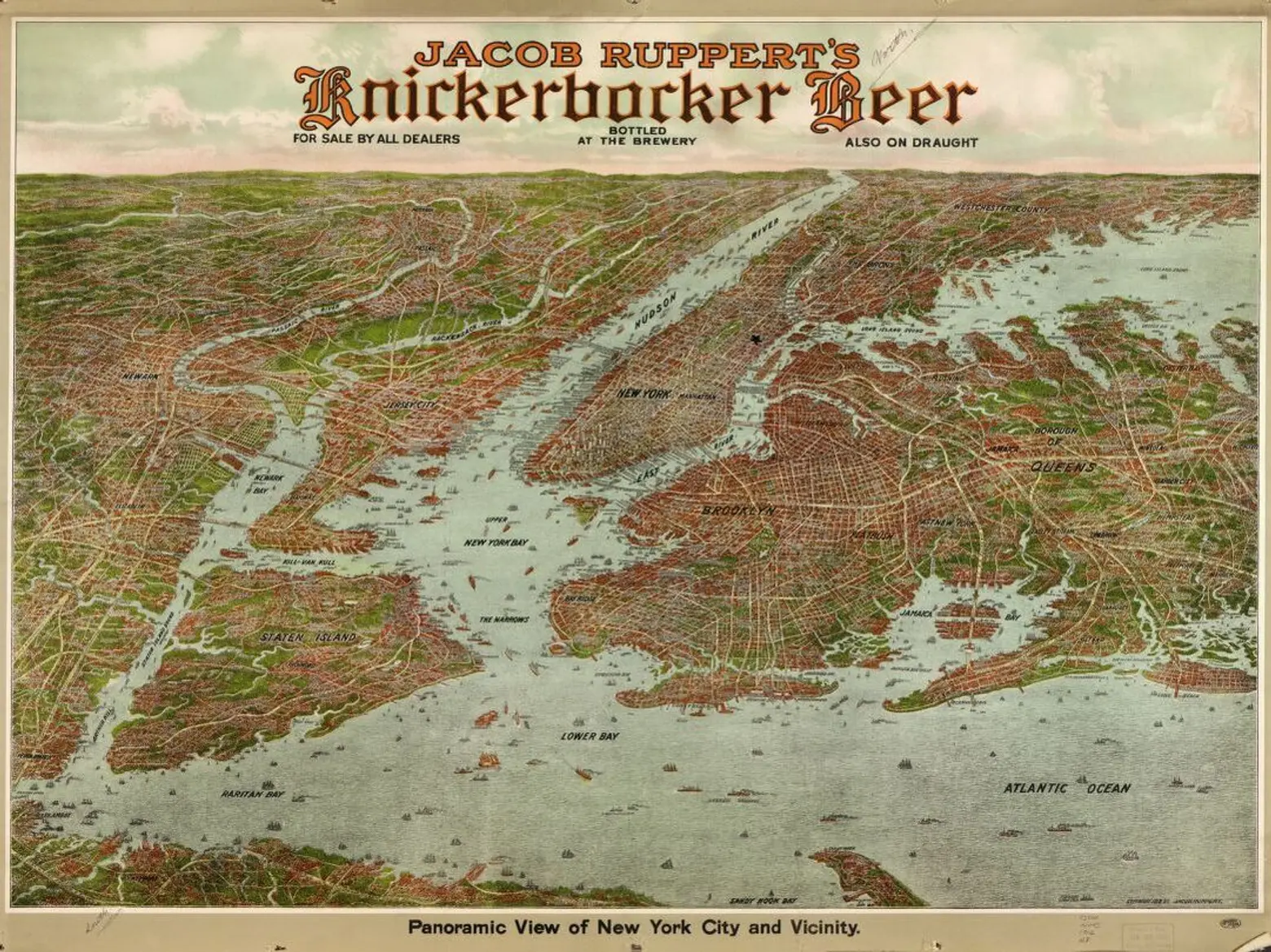

Jacob Ruppert’s Knickerbocker Beer, 1912, via Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

If you spent the first weekend of October hoisting lager and Oomph-ing it up for Oktoberfest, then you joined a long and proud tradition of German beer production and consumption in New York City. In fact, New York’s German-owned breweries were once the largest beer-making operations in the country, and the brewers themselves grew into regional and national power-players, transforming Major League Baseball, holding elected office, and, perhaps most importantly, sponsoring goat beauty pageants in Central Park. While brewing flourished in both Manhattan and Brooklyn throughout the 19th century, the city’s largest breweries were clustered in Yorkville. In fact, much of the neighborhood’s storied German cultural history can be traced to the rise of brewing in the area, and the German-language shops, cultural institutions and social halls that sprang up to cater to the brewery workers.

New York’s first City Hall, the Dutch Stadt Huys, was built in 1642 as the Stadt Herbert, or the City Tavern, which sold Ale. In fact, Ale was the standard variety of beer sold in New York City until the mid-19th century (consider that Civil-War-era McSorley’s is an Ale House). Why? It was German immigrants who introduced lager to NYC.

Large-scale German immigration to New York City began in the 1840s. By 1855, New York City was home to the world’s third-largest German-speaking population behind Berlin and Vienna. According to FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, and their book, “Shaped by Immigrants: A History of Yorkville,” New York’s German community, which had first congregated in “Klein Deutchland” in today’s East Village, began moving to Yorkville in the 1860s and 1870s, drawn by new housing and improved transportation.

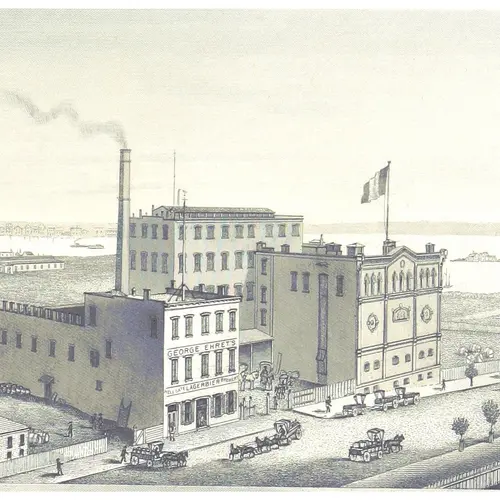

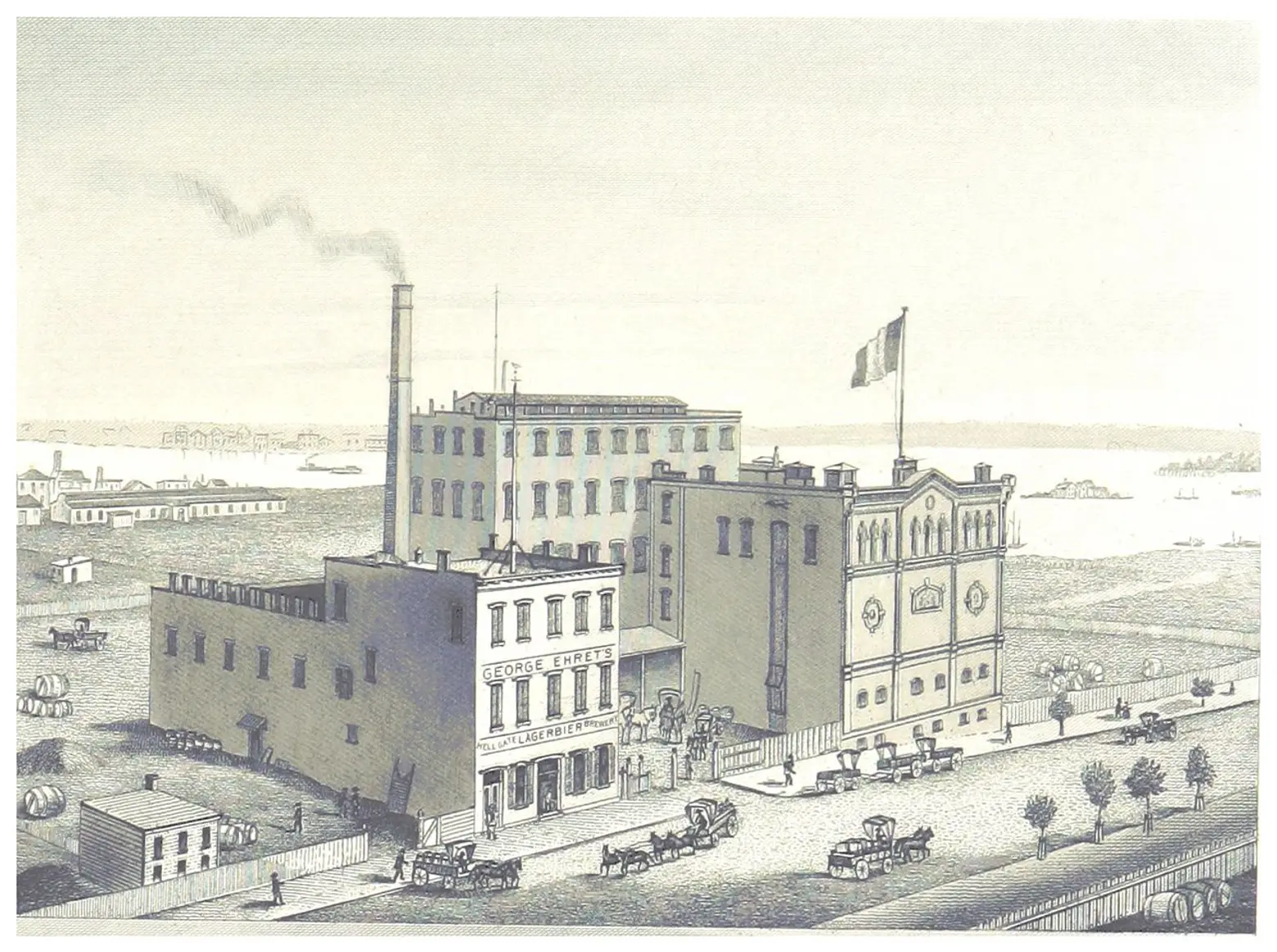

George Ehret’s Hell Gate Brewery via British Library/Flickr cc + Wiki Commons

As New York’s German community moved uptown, so did New York’s Breweries. In 1866, George Ehret founded his Hell Gate Brewery between 92nd and 93rd Streets and Second and Third Avenues. Ehret’s brewery was so large, he built his own well to pump 50,000 gallons of fresh water every day and turned to the East River for 1,000,000 daily gallons of saltwater.

Though Ehert presided over the largest brewery in the nation, he was not the only brewer on the block. The year after Ehret’s Hell Gate Brewery opened, Jacob Ruppert opened a rival brewery across the street. His operation sprawled between 91st and 92nd Streets and Second and Third Avenues. Ruppert also celebrated his local bonafides, calling his most popular beer Ruppert’s “Knickerbocker Beer.”

Lest the two biggest names in beer not be enough for one street corner, the George Ringler Brewery posted up at 92nd Street and Third Avenue in 1872. And the parade of suds did not end there. According to the 1911 Yearbook of the United States Brewers Association, the John Eichler Brewing Co. sat at 128th Street and Third Avenue. Central Brewing Company packed the pints at 68th Street and the East River. Peter Doelger, who’s signage you can still see at Teddy’s Bar in Williamsburg, was on 55th Street east of First Avenue. Elias Henry Brewing presided over 54th Street, and of course, F. M. Shaefer stood tall at 114 East 54th Street.

According to FRIENDS of the Upper East Side, by the 1880s, nearly 72 percent of all New York brewery workers were of German heritage. Accordingly, New York’s brewing culture was based on the systems and traditions that had prevailed in Germany since the Middle Ages. For example, German breweries traditionally required their employees to live in brewery-owned housing, known as Brauerherberge, or “brewer hostels,” which were overseen by brew-masters and company foreman. The same was true for employees in Yorkville, who lived close to their breweries. Since most of the workers living in brewer hostels were single men, employees with families in Yorkville were usually given accommodations in brewery-owned tenements in the neighborhood. And the brewers didn’t just own the hostels, they owned almost all aspects of their businesses. In fact, Jacob Ruppert owned an ice factory, stables, a barrel-making outfit, and a chain of banks.

But nothing brought beer to market better than owning the saloon itself. Here was the deal: the brewers would own the bars, and lease them to saloon-keepers; in return, the spot would sell only the owner’s beer. (There was no such thing as ‘100 beers on tap’ it was Ruppert’s or Hell Gate or Schaefer etc.) Ruppert was famous for his Knickerbocker Inn, but Ehret was “the king of beer corners:” He owned a whopping 42 saloons in New York by 1899.

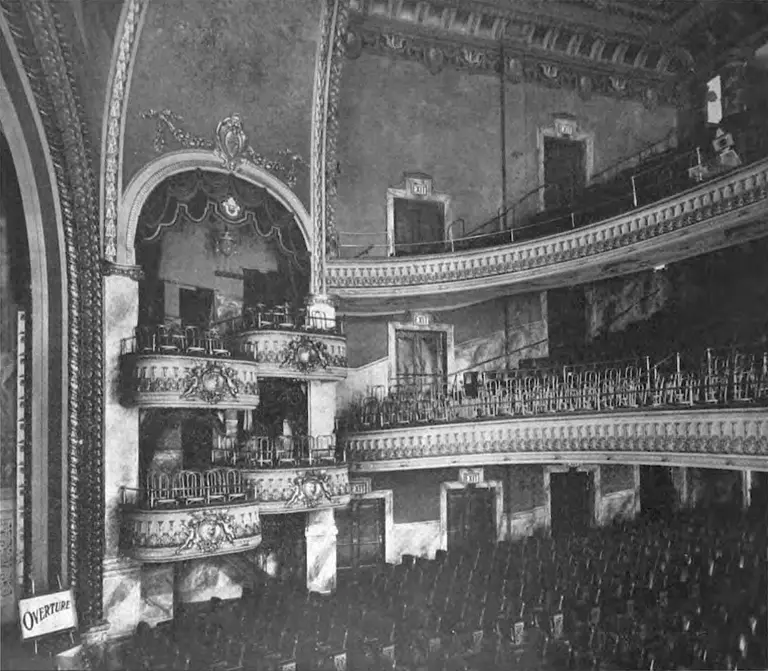

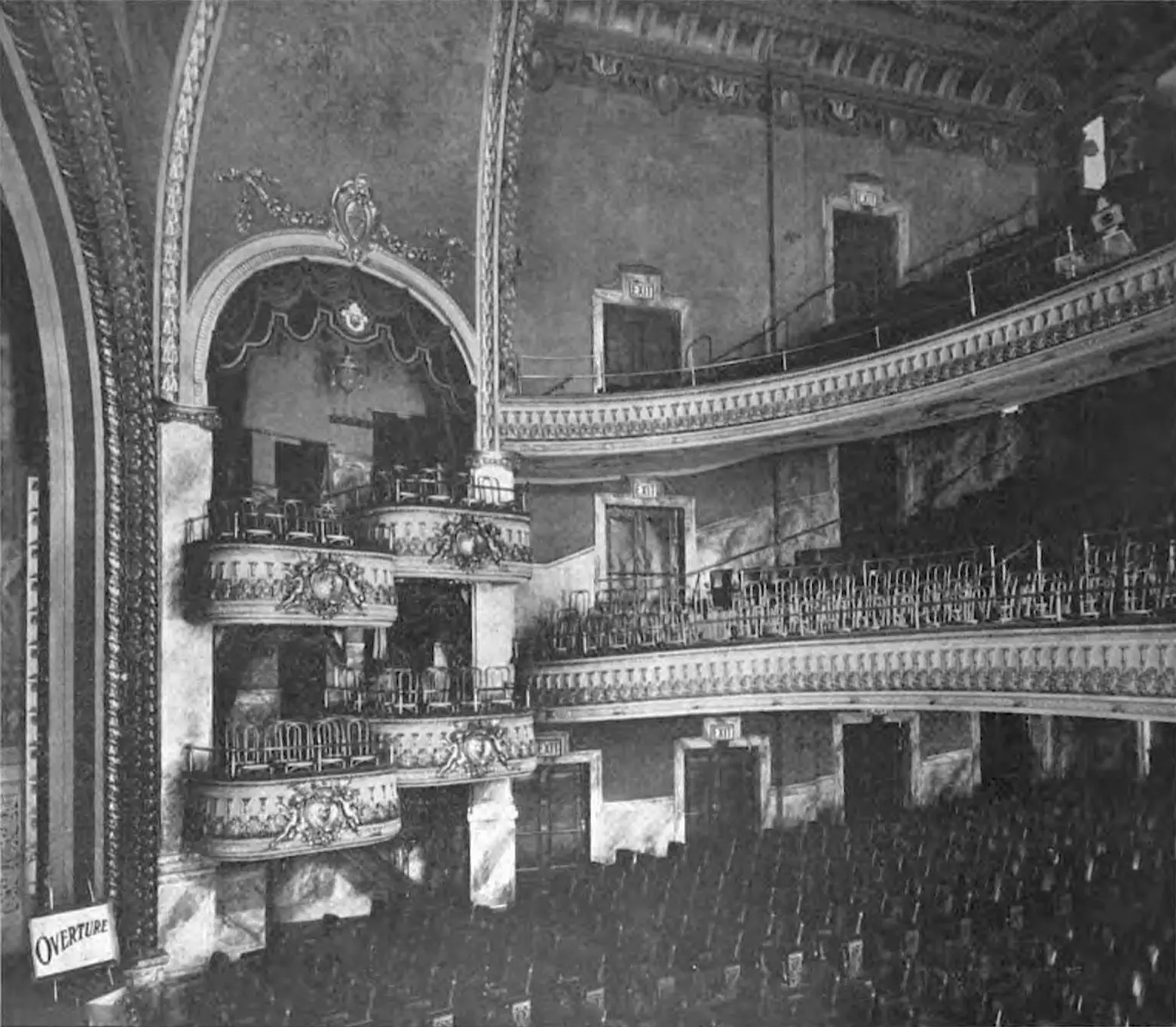

Yorkville Theater, 86th St. between Lexington and Third, via Wikimedia Commons

But the brewers didn’t just build beer corners. Because breweries required such close consolidation of life and work, a full brewing community flourished in Yorkville. Beer halls, beer gardens, and saloons became centers of social life, and hosted all kinds of cultural and professional activities, from vaudeville revues to union meetings.

Meanwhile, 86th street grew into the neighborhood’s main drag, earning the moniker “German Broadway,” providing everything from cabaret to cabbage, lined with German-language shops, restaurants, and theaters. For example, The Doelger Building, built by the Doelger brewing family, and still standing at 1491 Third Avenue at 86th Street, was built as a music hall, with space for stores, a cabaret, office space, and a “hall for public assembly.”

In fact, German life was so intimately tied to the brewers, that the neighborhood got its news from Ruppert. He published the German-language newspaper New Yorker Staats-Zeitung.

That intimacy prevailed among the brewers themselves: For example, Ehert and Ruppert jointly owned a silk mill, they vacationed together, their families intermarried, and they were both loyal members of the Arion Society of New York, a German-American musical society. Like the Arion Society, many of the breweries in Yorkville were felled by the anti-German sentiment in America during and after WWI, and many more were shuttered during Prohibition.

Here is where the fates of Ehert and Ruppert diverge (and converge again). Ehret had gone to Germany in 1914 to recover from an illness, thinking the Alpine air might do him good. But WWI broke out while he was overseas, and he was stranded in Germany during the war, unable to return to the United States until mid-1918. In the meantime, Ehert’s business and property were seized by the US Government as “alien property,” even though Ehert was a naturalized citizen.

Bain News Service, P. (1923) Harry New Postmaster General, Dr. Chas. Sawyer President’s physician, Albert Lasker, Jacob Ruppert & Pres. Warren Harding at Yankee Stadium, 4/24/23 baseball. 1923 The Library of Congress.

Conversely, Jacob Ruppert Jr. was as All-American as it gets. By the time his father, the founder, Jacob Ruppert Sr., died in 1915, Ruppert Jr. had already served four terms in the House of Representatives and was part-owner of the Yankees. As president of that ball club, he was responsible for signing Babe Ruth in 1919, and for building Yankee Stadium in 1922.

Ehert regained control of the Hell Gate Brewery after WWI, but Prohibition hit him hard. Though he was determined to hang on until the Volstead Act was repealed and keep his workers on for the duration, Ehert died in 1927. When the Act finally was repealed in 1933, Ruppert expanded his own Brewery with 300 additional workers and bought Hell Gate in 1935.

Ruppert Jr. himself died in 1939, but the Brewery that bore his name survived, sending the scent of barley and hops through the streets of Yorkville until 1965. In the 70s, the site of Ruppert’s Brewery became an urban renewal project known as Ruppert Towers and is now a 4-building condo complex called Ruppert Yorkville Towers.

But, in 2014 the red brick of Ruppert’s brewery once again made an appearance in Yorkville. That March, workmen were excavating Ruppert Playground on East 92nd Street as developers prepared to turn the community space into a 35-story apartment building. Serendipitously, the bulldozers unearthed two underground brick archways that had been part of the brewery. For a brief moment, the Brew Man was back in town.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.