Jane Jacobs’ NYC: The sites that inspired her work and preservation legacy

Washington Square Park via Wiki Commons; Jane Jacobs via Wiki Commons

Jane Jacobs’ birthday on May 4 is marked throughout the world as an occasion to celebrate one’s own city — its history, diversity, and continued vitality. “Jane’s Walks” are conducted across the country to encourage average citizens to appreciate and engage the complex and dazzling ecosystems which make up our cityscapes (Here in NYC, MAS is hosting 200+ free walks throughout the city from today through Sunday). But there’s no place better to appreciate all things Jane Jacobs than Greenwich Village, the neighborhood in which she lived and which so informed and inspired her writings and activism, in turn helping to save it from destruction.

Her Home

Google Street View of 555 Hudson Street today

Google Street View of 555 Hudson Street today

Jane Jacobs’ home still stands today at 555 Hudson Street, just north of Perry Street. A modest 1842 rowhouse which had been substantially altered in 1950, it is here that Jane and her husband Robert raised their family and she wrote the epic tome “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” In 2009, GVSHP got the block co-named “Jane Jacobs Way,” visible at the Bank Street end of the block.

“The Sidewalk Ballet” and “Eyes on the Street”

Grove Street in the West Village, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Grove Street in the West Village, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr

Jacobs was inspired by what she saw outside her door, on active, mixed-use streets like Hudson Street, to formulate her theories of ‘the sidewalk ballet’ and ‘eyes on the street’ as essential elements to the healthy functioning of cities and neighborhoods. Whereas the conventional wisdom of urban planning of the day was that only orderly spaces with segregated uses and wide open space could succeed, Jacobs saw how the dense, messy, mixed nature of people and activities on her doorstep kept her local shops well patronized, her streets safe with watchful eyes, her neighborhood vibrant, and her neighbors interconnected.

The West Village as “blight”

Crane with wrecking ball mounted on the trestle to dismantle the High Line. Photo by Peter H. Fritsch (1962). Photo courtesy of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation/Fritsch Family Collection. (MORE HERE)

Crane with wrecking ball mounted on the trestle to dismantle the High Line. Photo by Peter H. Fritsch (1962). Photo courtesy of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation/Fritsch Family Collection. (MORE HERE)

Believe it or not, in the 1960s, Robert Moses declared the West Village west of Hudson Street blighted, and planned to tear it all down in the name of urban renewal. Of course, this was a very different West Village than today, and indeed the deactivated High Line, the crumbling West Side piers, the looming West Side Highway, and the somewhat decrepit waterfront warehouses, factories, and sailors’ hotels did not have quite the polish of today’s West Village. Nevertheless, this was Jane Jacobs’ turf, and where Moses saw blight, she saw diversity and potential.

Jacobs led the successful effort to defeat Moses’ urban renewal plan and preserve this charming and modest section of the West Village. Not long after, half of the area was landmarked in 1969 as part of the Greenwich Village Historic District, and much of the remainder was landmarked in 2006 and 2010 through preservation campaigns lead by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

Jacobs’ Design Hand

West Village Houses. Courtesy New York City Municipal Archives

West Village Houses. Courtesy New York City Municipal Archives

The West Village Houses, 42 walk-up apartment buildings located on six blocks in the Far West Village west of Washington Street between Morton and Bethune Streets, are the only buildings anywhere that Jane Jacobs had a direct hand in designing. Located within the area Moses had designated for urban renewal, and in the path where the High Line once ran (it was dismantled here in the early 1960s), West Village Houses evolved from the community’s alternative plan for modest, walk-up, human-scaled infill housing, as opposed to the often faceless, interchangeable “towers-in-the-park” Moses propagated across New York City.

When Moses’ plan was defeated, Jacobs and her neighbors went to work devising a scheme for housing on the empty and underutilized lots cleared by the demolition of the High Line, which would embody the characteristics they loved about their West Village. In addition to the low scale, they opted for shared communal space in the rear and side yards, brown brick, and shallow setbacks from the sidewalk that approximated the small front yards or areaways of rowhouses and tenements. The buildings were placed at slight angles or pushed slightly forward or backward to create the variation in form one normally saw over time in the accretion of an urban neighborhood. They also ensured that the development would be affordable to the teachers, artists, shopkeepers, and civil servants that populated the then-modest neighborhood.

There was much resistance to the plan from the government, and many delays and roadblocks. When it was eventually completed in 1975, cost overruns meant the West Village Houses were a somewhat stripped-down, spartan version of what was originally envisioned. Nevertheless, they both fit in with the neighborhood and provided a much-needed stable residential community, in an area which was losing industry at a clip, and which many New Yorkers might have considered too seedy or raffish to live in.

Cars Out of Washington Square

Last car through Washington Square Park, 1958. Tankel Collection, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

Last car through Washington Square Park, 1958. Tankel Collection, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

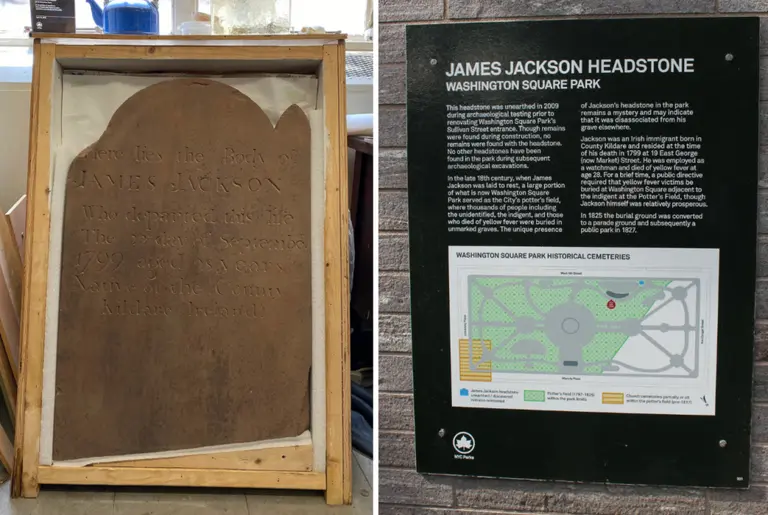

Today many are surprised to learn that cars and buses used to run through Washington Square for much of the mid-20th century. In fact, the large flat area of the park around the fountain and the arch is a vestige of the time when motor vehicles used the park as a turnaround.

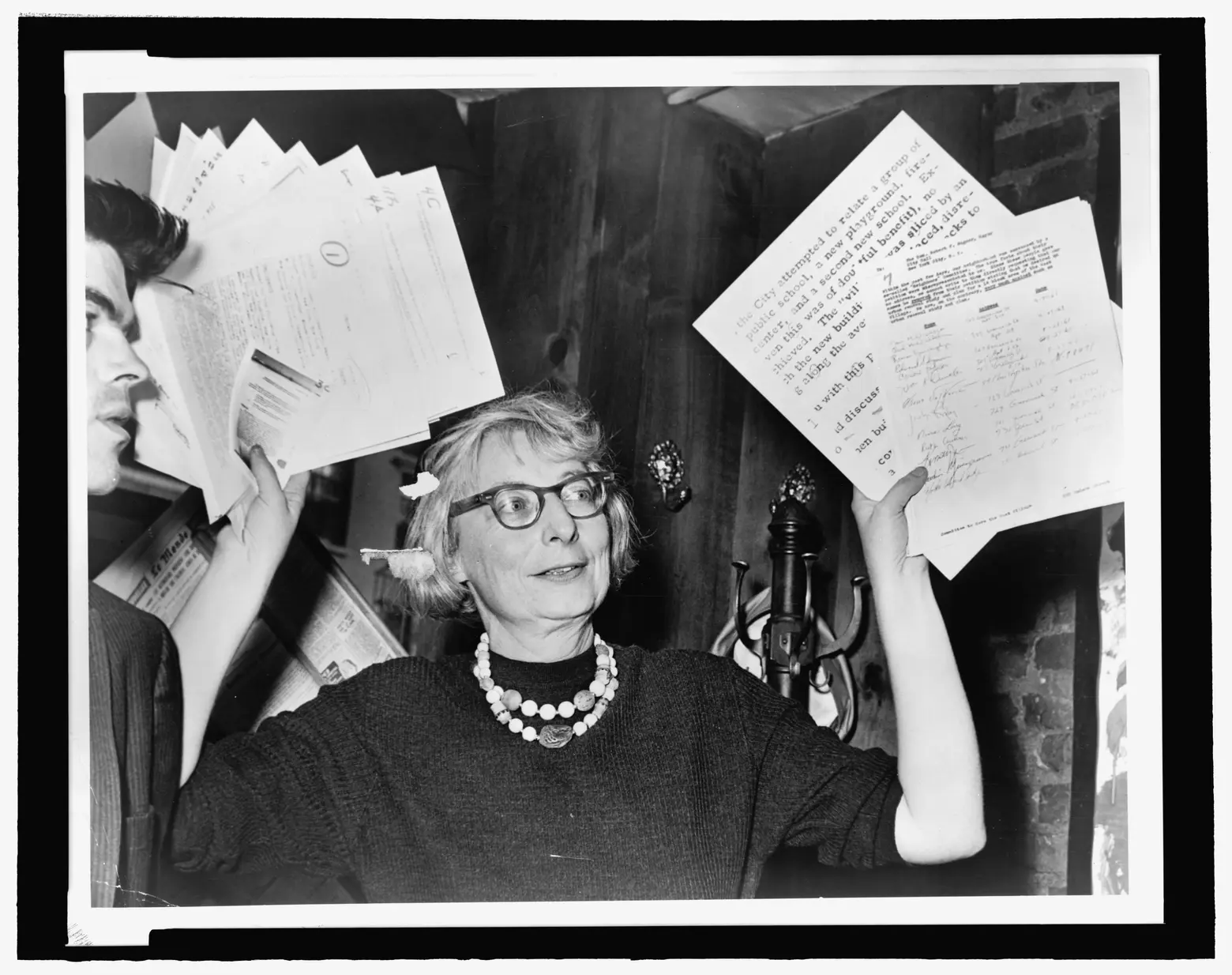

Jane Jacobs was not a fan of the automobile and its impact upon cities and neighborhoods. Along with her friends and neighbors, she waged the fight to get cars and buses out of the square, staging protests, gathering petitions, and lobbying city officials. Not only did the City not want to ban cars, they wanted to build an extension of Fifth Avenue through the park which would serve as an access route to the Lower Manhattan Expressway planned at the time, thus making Washington Square little more than the greenery surrounding a highway on-ramp.

Jacobs and fellow activist Shirley Hayes would have none of it. The City tried to entice them with “alternative” plans for allowing cars to remain in the park, including building a pedestrian passageway over the cars. But Jacobs, Hayes, and company persevered, and in the late 1950s, cars were banned from the park on a trial basis, and in the 1960s the ban was made permanent.

Saving Soho, the South Village, and Little Italy

Had Robert Moses had his way instead of Jane Jacobs, the neighborhoods of SoHo, the South Village, Nolita, and Little Italy would not exist today. That’s because in the 1940s and 50s Moses wanted to build a superhighway called the “Lower Manhattan Expressway” along present-day Broome Street, connecting the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges to the Holland Tunnel, thus making automobile access between Long Island and New Jersey easier via Lower Manhattan.

Had Robert Moses had his way instead of Jane Jacobs, the neighborhoods of SoHo, the South Village, Nolita, and Little Italy would not exist today. That’s because in the 1940s and 50s Moses wanted to build a superhighway called the “Lower Manhattan Expressway” along present-day Broome Street, connecting the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges to the Holland Tunnel, thus making automobile access between Long Island and New Jersey easier via Lower Manhattan.

Moses saw the need to accommodate regional motor vehicle traffic as paramount. He also saw the neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan which stood in the way of his highway plan as blighted and anachronistic. And in some ways he was right – what we now call SoHo (which did not acquire that name until the late 1960s) was a sea of outdated and underutilized factory buildings, while the neighborhoods of the South Village and Little Italy were working-class neighborhoods formerly populated with Italian immigrants, whose children and grandchildren were moving to the outer boroughs and suburbs.

But Jane Jacobs and many of her neighbors saw something different. They saw a sea of potential, and neighborhoods which may not have been growing, but which were holding on, with residents who were invested in their communities and a diversity of activities and types of people that cities needed. She also saw what happened to the Bronx when the Cross-Bronx Expressway cut that borough in half to accommodate motor vehicle access from Westchester and Connecticut to New Jersey; previously stable working-class neighborhoods were destroyed, and the borough began a precipitous decline which lasted for decades.

And it wasn’t just the neighborhoods directly in the proposed highway’s path along Broome Street that were threatened; Moses envisioned a series of on and off ramps connecting the expressway to major Manhattan arteries along its length, slicing through the surrounding neighborhoods. One such connector would have stretched up along West Broadway and LaGuardia Place through Washington Square (see above), thus turning Greenwich Village’s Lower Fifth Avenue into a speedy accessway to New Jersey or Long Island (if you’ve ever wondered why LaGuardia Place north of Houston Street is so wide, with a swath of gardens along its eastern edge, it’s because Moses had planned to turn the entire width into a connector to the Lower Manhattan Expressway).

Jacobs and her fellow activists from Lower Manhattan fought the plan tooth and nail, shaming public officials, disrupting meetings, and organizing their neighbors. The plan remained active well into the 1960s, though it died a few deaths before the final nail in the coffin in 1968.

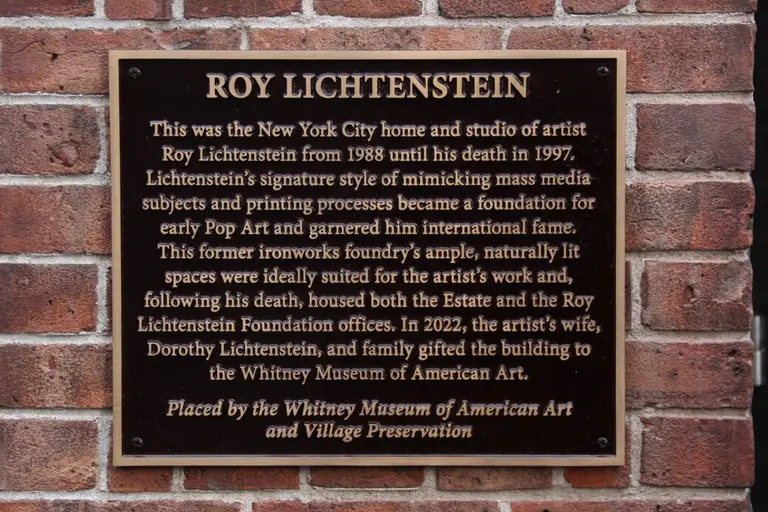

As the chairman of the Committee to save the West Village, Jane Jacobs holds up documentary evidence at a press conference at the Lions Head Restaurant at Hudson & Charles Streets in 1961. Via Wiki Commons.

Jane Jacobs not only shaped the way we see our city but quite literally shaped how it worked and which areas survived. Greenwich Village and surrounding neighborhoods owe a great debt of gratitude to her for her writing and her unrelentingly effective activism, which is no doubt why she is sometimes referred to as “Saint Jane” in these parts.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED: