Interview: Famous photojournalist Steve McCurry on authenticity, truth, and trust in today’s world

Steve McCurry, “Monks Praying at Golden Rock,” Kyaikto, Myanmar, 1994. Courtesy Cavalier Galleries

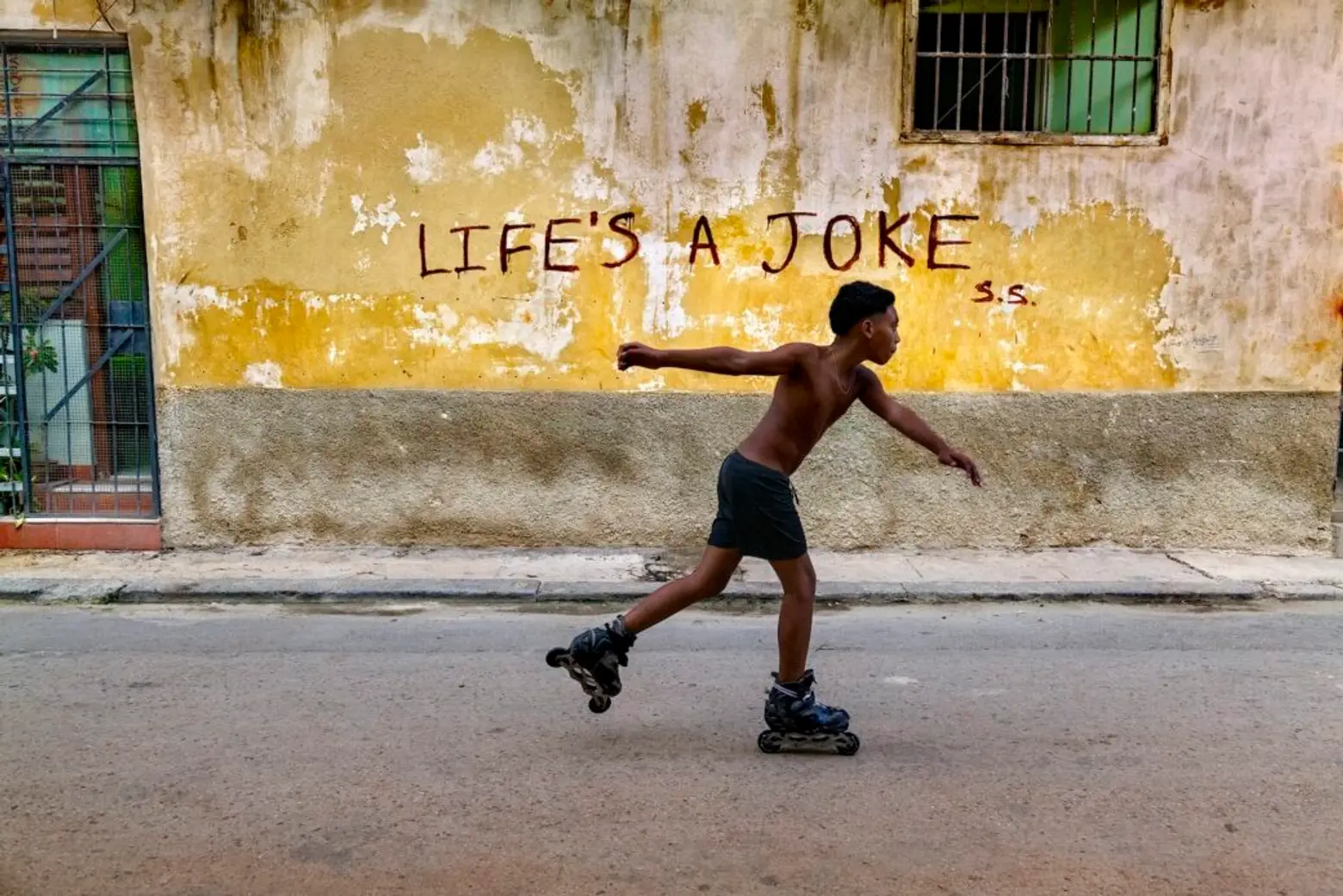

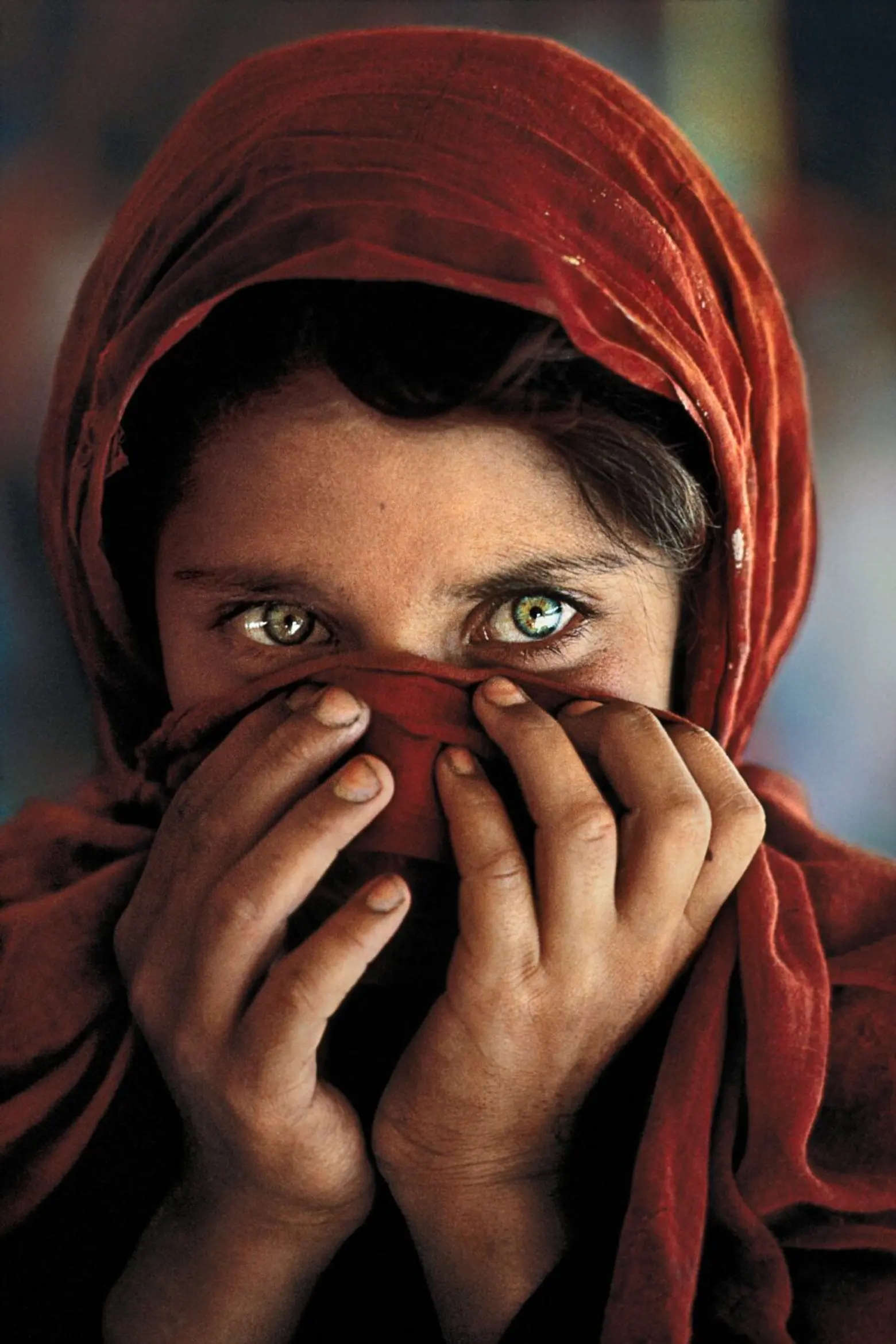

As the spring arts season awakens, an exhibition of note will be ending its run at the Cavalier Galleries in Chelsea: Now through March 30, take the opportunity to experience work by American photojournalist Steve McCurry. As one of our most celebrated contemporary photographers, McCurry is best known for his unforgettable portrait of 12-year-old Afghan refugee Sharbat Gula, the “Afghan Girl” who gazed from the cover of National Geographic magazine in 1985. The current solo exhibition marks the release of McCurry’s new book, “Devotion: Love and Spirituality” (Prestel, 2024). The show features over 30 photos that span more than four decades, captured during McCurry’s visits to Cuba, Ethiopia, India, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Tibet. The images are both timeless and current, featuring human struggles and daily lives.

McCurry’s career took flight in the 1980s, when he crossed the Pakistan border into rebel-controlled areas of Afghanistan, dressed in Afghani garb, just before the Soviet invasion. The images he captured revealed the brutality of the Russian invasion and the harsh toll of war to the world outside for the first time.

Sharbat Gula’s luminous green eyes in the iconic “Afghan Girl” portrait became a symbol for the struggle of Afghan refugees newly arrived in Pakistan. The young orphan girl had traveled to that country by foot with her remaining family.

McCurry’s subsequent work covers seven continents and offers a rare, clear-eyed view of conflicts and rituals, and daily expressions of cultures both ancient and modern. His photos always put the human element in full focus in the way that imbued “Afghan Girl” with such power.

In addition to having been inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame in 2019, McCurry has received numerous prestigious industry awards. In addition to the Chelsea exhibition, a simultaneous exhibition will be on view at Cavalier Ebanks Galleries at 175 Greenwich Avenue in Greenwich, Connecticut through March 9.

In an exclusive interview, McCurry shares some insights with 6sqft on ways that his work in war-torn communities resonates just as much–if not more–in today’s world, along with what has changed since he introduced “Afghan Girl” to the world.

6sqft: When you share your photographs, what context are you hoping to–or intending to–provide?

McCurry: Through my photographs, I aim to offer a glimpse into the diverse lives and cultures of people around the world, fostering understanding and empathy across borders. My goal is to portray the universal human experiences and emotions that transcend language and cultural barriers, creating a sense of connection and appreciation for our shared humanity.

When you were able to witness, photograph, and share the photos of Afghanistan after the Russian invasion and countless other lands in violent conflict, you provided a window on the unforgiving brutality of war, that people elsewhere would otherwise be isolated from and perhaps unaware of. In today’s world, where photos and footage from every corner are beamed immediately far and wide, how do you think people’s reaction to this kind of tragedy has changed? Are people more, or less, shocked by what they see? Are they perhaps inured?

There is always that balance between risking one’s life for a picture and sometimes being overly cautious and timid. I don’t think it’s worth getting killed for a picture but sometimes you need to take a risk and you just have to hope for the best.

There is a degree of calculated risk inherent in covering conflicts or other dangerous situations, but this is inevitable in the work because as a photographer, you go where the stories that need telling tend to be. Important events need to be recorded; they become historical documents. A picture can galvanize people into action. No one is thinking about the artistic effect while documenting the tragedy of war. It is about proof of what happened. These were important, pivotal times for these countries and I wanted to go there and see the situations for myself and tell their stories.

Do you find “ordinary” people throughout the world are more (or possibly less) receptive to being photographed now than decades ago? How has their reaction changed?

I think most people actually want to have their picture taken. If you win their confidence and their trust, people will open up and allow you to photograph them. I find that once you explain what you are doing and you can bring them into your process, people are very happy to cooperate and let you take their picture. You usually have a period or two where people give you that amount of time and then their curiosity runs out. You have to work quickly, get your shot, make them relaxed, and that’s it.

There’s a certain kind of truth that is revealed in a photograph. How do you feel people’s reception to photographs and photojournalism has changed of late, if it has–for example, in context of the rise of AI-generated photos, earlier photo manipulation capabilities, and the attendant rise in people’s desire to manipulate the “truth”–or their mistrust in it. Do you feel people are generally less trustful of photos as “truth?”

There’s a growing awareness of the potential for images to be altered or fabricated, leading to a heightened skepticism among viewers. As a result, there’s a greater emphasis on transparency and authenticity in photography, with audiences demanding more accountability and integrity from photographers to uphold the credibility of the medium.

Looking at your most recent exhibition and book theme, has your focus changed or shifted?

In my most recent exhibitions and my book, “Devotion,” I’ve continued to explore the timeless themes of humanity, culture, and the human condition. While my focus remains steadfast on capturing the beauty and diversity of our world, I’m always open to evolving perspectives and new subjects that inspire me, ensuring that my work remains relevant and resonant with audiences.

What’s next for you, do you see a new direction?

As I continue my journey as a photographer, I’m constantly seeking new challenges and opportunities to explore different aspects of the human experience. While my core interest in documenting cultures and people remains unchanged, I’m intrigued by the potential of emerging technologies and storytelling mediums to further enhance and diversify my work. Whether it’s through experimenting with new photographic techniques or delving into multimedia projects, I’m committed to pushing boundaries and expanding the scope of my artistic vision while staying true to my passion for storytelling and human connection.

“STEVE MCCURRY: The Importance of Elsewhere” is on view (now extended through March 30th) at Cavalier Galleries, 530 West 24th Street, NY, NY and through March 9th at 175 Greenwich Avenue, Greenwich, Connecticut.

RELATED: