From the ‘Queens Riviera’ to Robert Moses: The history of Rockaway Beach

Eleven blocks of Rockaway Beach will be closed this summer due to erosion, but that’s just one setback in a long history of resilience on the peninsula. Four-and-a-half miles of the beach are open right now, with every block steeped in history. The Rockaways ushered Henry Hudson into the New World; Walt Whitman into paradise; Hog Island into oblivion; and the Transatlantic Flight into existence.

As “the brightest jewel within the diadem of imperial Manhattan,” the pristine beaches of the “Queens Riviera” became the preferred summer locale for New York’s most illustrious citizens. Later, the “people’s beach” at Riis Park helped make the Rockaways accessible to more New Yorkers. From, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, to Patti Smith to Robert Mosses, everybody wanted to be at Rockaway Beach.

An illustration of the Half Moon in the Hudson River in 1609, via Wiki Commons

An illustration of the Half Moon in the Hudson River in 1609, via Wiki Commons

“Rockaway” is derived from “Reckouwacky,” a Canarsie Native American word. It means “The place of our own people.” The Canarsie were the first people to live on the Rockaway Peninsula, and they were the first to see Henry Hudson arrive in New York.

When he made landfall in New York on September 3, 1609, Hudson anchored the Half Moon at Rockaway Inlet. One of his men wrote that the Canarsie people greeted the ship’s arrival with “every sign of friendship,” and came aboard to trade. Given such a warm reception, Hudson made Rockaway Inlet his first base of operations in New York and used the anchorage to explore Jamaica Bay.

Hudson was not the only illustrious name associated with the early history of the Rockaways. The Canarsie “sold” the Rockaways to the English in 1685, and Richard Cornell snapped up what is now Far Rockaway in 1687, establishing residence as the first European settler in the area in 1690. Cornell, founder of Cornell University, might be the most famous member of the family, but long before the School of Hotel Management was dolling out degrees, Benjamin Cornell was managing a hotel in the Rockaways.

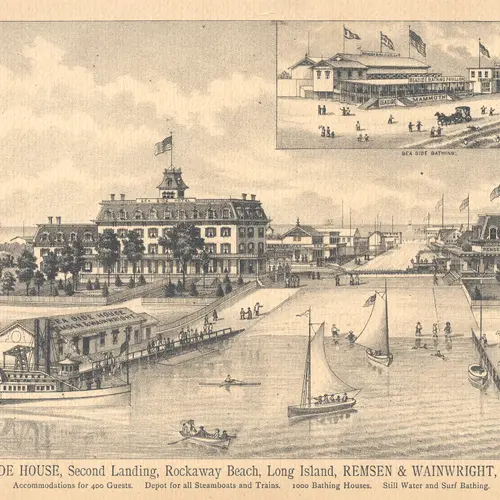

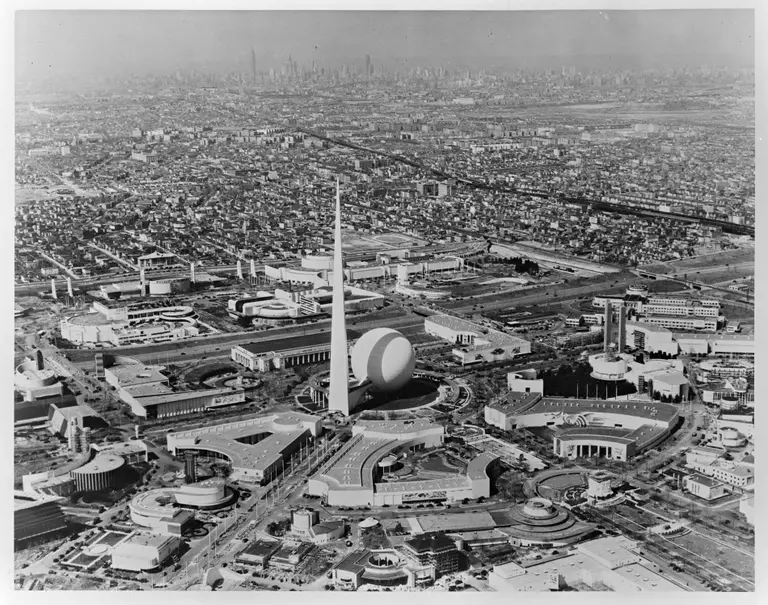

View of the luxurious hotels in the Rockaways, via Lancaster History

View of the luxurious hotels in the Rockaways, via Lancaster History

He established Rockaway Bath in 1816, beginning Rockaway’s life as a resort destination. Stagecoach lines brought wealthy people from Long Island out to Cornell’s Bath to take in the salt air (with the help of their horses who backed bathing houses into the water, so that fusty beachgoers could “swim.”) The enterprise was so successful that the entire Cornell homestead became the Marine Pavilion Hotel and Resort in 1833. The Marine Pavilion was one of the most luxurious hotels in the country and billed as “a large and splendid edifice standing upon the margin of the Atlantic.” It was also the most expensive hotel ever constructed at the time, costing $43,000 to erect.

A boardwalk bathing pavilion in 1903, via NYPL

A boardwalk bathing pavilion in 1903, via NYPL

The hotel made “summer” into a verb in the Rockaways. Well-to-do 19th-century sun-worshipers came pouring in for the season, using the hotel’s private turnpike from Long Island, or the newly opened ferry service to shuttle across the bay from Brooklyn. The Pavilion was so chic, it attracted assorted Astors and Vanderbilts and became a destination for New York’s literati, counting Washington Irving, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Walt Whitman as frequent guests.

The Marine Pavilion burned down in 1864, but by the end of the decade, the resort boom would be back and better than ever, thanks to the Rockaway Beach Railroad, which opened in 1868, and the LIRR, which extended service to the Rockaways in 1873. As public transit proliferated on the peninsula, Rockaway became accessible to New Yorkers trapped in the stifling tenements of an un-airconditioned city. Irish immigrants, in particular, made their way to Rockaway, and the peninsula became known as the Irish Riveria.

The Marine Pavilion burned down in 1864, but by the end of the decade, the resort boom would be back and better than ever, thanks to the Rockaway Beach Railroad, which opened in 1868, and the LIRR, which extended service to the Rockaways in 1873. As public transit proliferated on the peninsula, Rockaway became accessible to New Yorkers trapped in the stifling tenements of an un-airconditioned city. Irish immigrants, in particular, made their way to Rockaway, and the peninsula became known as the Irish Riveria.

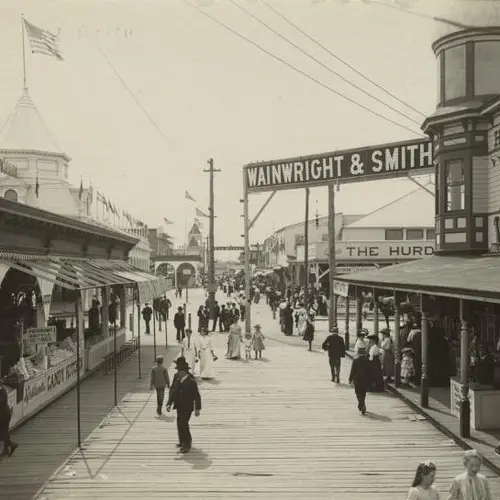

The Rockaway boardwalk in 1903, via NYPL

The Rockaway boardwalk in 1903, via NYPL

As Rockaway welcomed a wider array of summer revelers, the beach scene became a bit more rollicking. The Wave, Rockaway’s local newspaper reports:

As the gross receipts for all the establishments in Rockaway [rose] for the 1876 season ($1,180,000), complaints of murder, housebreaking, gambling, vice, unlicensed liquor sales, numerous places selling liquor on the same license, theft, assault, pickpocketing, corrupt and drunken sheriffs fighting amongst themselves, and last of all the confidence men operating on the peninsula were frequent.

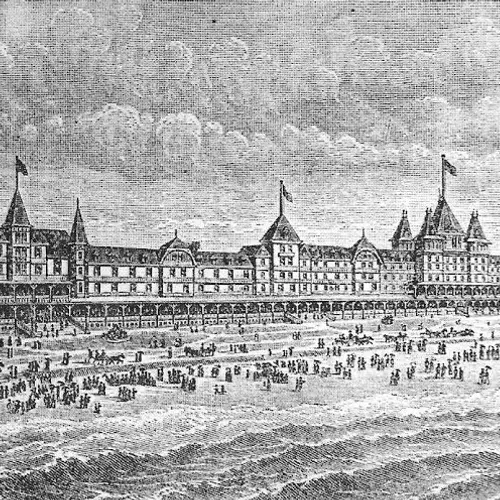

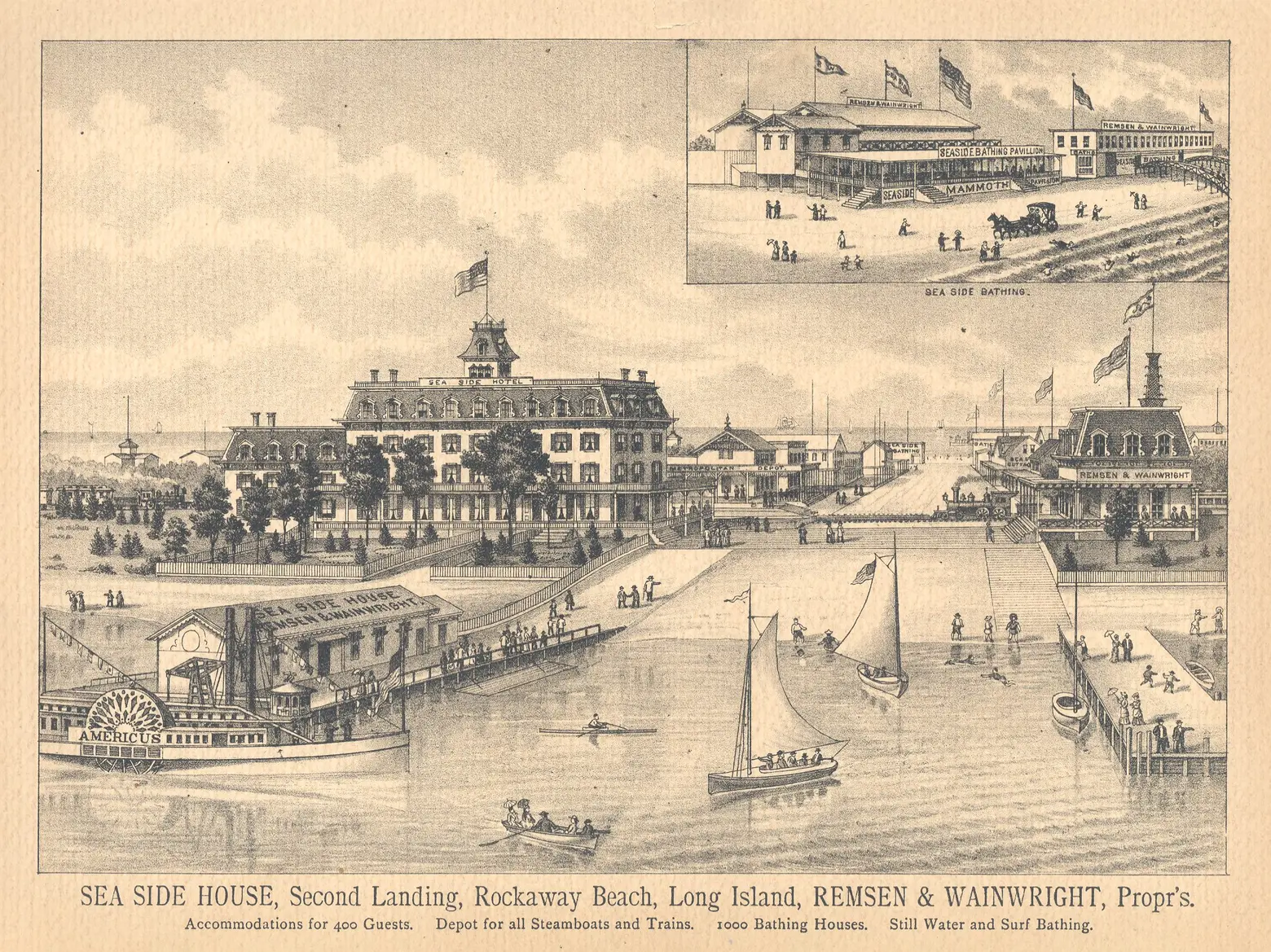

A lithograph of the Rockaway Beach Hotel, via Vincent Seyfried and William Asadorian, “Old Rockaway, New York, in Early Photographs,” Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 2000

A lithograph of the Rockaway Beach Hotel, via Vincent Seyfried and William Asadorian, “Old Rockaway, New York, in Early Photographs,” Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 2000

This intoxicating 19th-century bungalow bash came to a head in the ill-fated Rockaway Beach Hotel, billed as the largest hotel in the world. The mammoth structure stretched 1,180 feet from Beach 116th Street to Beach 112th Street, could accommodate 7,600 guests, and cost $1.5 million to build in 1879! Complete with a reported “100,000 square feet of piazzas,” and an observation deck on the roof, the grand summer palace was the Titanic of hotels: it went down so fast only a wing of the hotel was ever open to the public, and only then for a single month, in August 1881. The whole place was torn down in 1884.

Speaking of going under, the entire Seaside section of the Peninsula, from Beach 102nd Street to Beach 106th Street, burned from beach to bay in 1882, and an 1883 hurricane pummeled the Rockaways so hard it wiped Hog Island off the map, giving New York its very own Atlantis.

In the 20th Century, the Rockaways rose from the ashes and the waves to rival Coney Island as a summertime amusement paradise. Coney Island can lay claim to the world’s first enclosed amusement park, but Rockaway got its own Steeplechase in 1901, and with it, the original wooden Rockaway Boardwalk, which stretched from beach 59th Street to Beach 74th Street. Rockaway Playland followed the following year and brought the world the Atom Smasher, rollercoaster extraordinaire.

In the 20th Century, the Rockaways rose from the ashes and the waves to rival Coney Island as a summertime amusement paradise. Coney Island can lay claim to the world’s first enclosed amusement park, but Rockaway got its own Steeplechase in 1901, and with it, the original wooden Rockaway Boardwalk, which stretched from beach 59th Street to Beach 74th Street. Rockaway Playland followed the following year and brought the world the Atom Smasher, rollercoaster extraordinaire.

With the Coming of the First World War, Hercules and Ajax missiles joined the Atom Smasher on the Peninsula. The artillery was stationed at Fort Tilden, built in 1917 between what is now Riis Park and Breezy Point. Fort Tilden was decommissioned in 1978 and is now administered by the national park service.

Jacob Riis Park and bathhouse via Padraic/Flickr

Jacob Riis Park and bathhouse via Padraic/Flickr

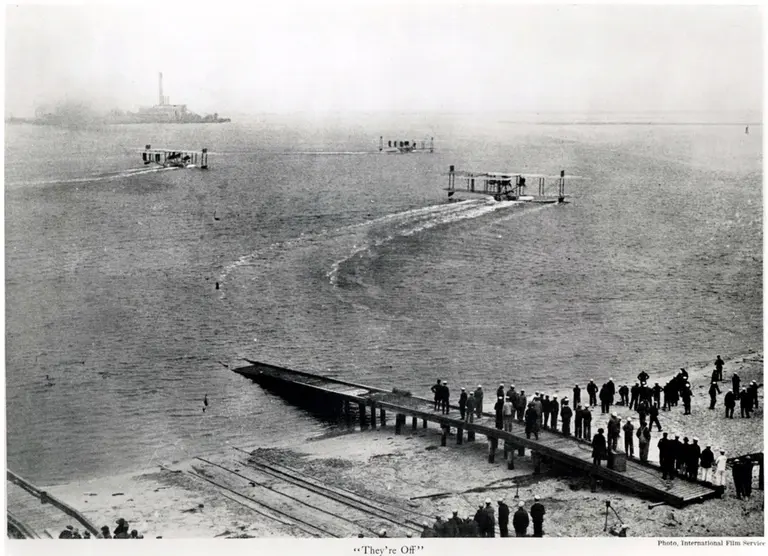

The Rockaways also hold a hallowed place in Aviation History: the world’s first Transatlantic Flight took off from the Rockaway Naval Air Station in May 1919. Today, we bound into the surf, not into the sky, from the Air Station, because Robert Moses built Jacob Riis Park on the site of the Station in 1934. The Art Deco bathing retreat modeled on Jones Beach, became “The People’s Beach,” attracting a working-class crowd Riis himself would have known well, and showing New York how the other half swims.

Riis Park wouldn’t be Moses’ only stamp on the Rockaways. The Prince of Parkways built the Marine Parkway Bridge, the Cross Bay Bridge, and Shorefront Parkway, cutting through neighborhoods and felling all structures within 200 feet of the boardwalk. At the same time, post-war suburban sprawl meant that the hot crowds who had once spent summer in the city and trekked out to the Rockaways looking for relief took their vacations elsewhere.

View of the Rockaway boardwalk today, showing some of the public housing. Via Robert/Flickr.

View of the Rockaway boardwalk today, showing some of the public housing. Via Robert/Flickr.

Both these factors diminished Rockaway’s vibrant beach community in the ‘60s, and Moses targeted the peninsula for slum clearance and urban renewal projects, building large-scale public housing at the Rockaways. These programs effectively took the city’s most underserved residents and moved them as far as possible from the resources they needed.

But, the Rockaways rose once again. When Hurricane Sandy made landfall in October 2012, it destroyed nearly three-and-a-half miles of the five-mile boardwalk and devastated homes in the area. The communities of the peninsula rebuilt, and the new boardwalk was fully finished July 4, 2016.

Rockaway Beach Surf Club via Mig Gilbert/Flickr

Rockaway Beach Surf Club via Mig Gilbert/Flickr

Today, the peninsula has become so popular, it’s been dubbed New York’s “next hot neighborhood,” and locals and day-trippers once again flood Riis Park, coming via ferry, beach bus, or subway. The Peninsula also offers quite a few quirks: The Rockaway Theater Company holds its productions in Fort Tilden; A reef made of ice cream trucks supports an entire ecosystem.

Surfers in the Rockaways, via Dakine Kane/Flickr

Surfers in the Rockaways, via Dakine Kane/Flickr

But perhaps the most special: the Rockaways are the only place in New York City you can legally surf, and it might be the surfers who sum up the beach best. Jimmy O’Brien, a surfer who writes The Wave’s “Down by the Jetty” column, says, “The Ocean is the Last Great Wilderness left on this Earth…Surfing has provided the opportunity to enter this foreign watery world…In our hyper-connected world, where the maps have been filled in, the routes have been calculated, our schedules have been pre-planned to the minute, it is with great anticipation, wonder and excitement that we look out at the sun-dappled horizon waiting for the waves to roll in.”

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

RELATED: