14 historic sites of the abolitionist movement in Greenwich Village

As this year marks 400 years since the first African slaves were brought to America, much attention has been paid to what that means and how to remember this solemn anniversary. The city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission issued a story map highlighting landmarks of the abolitionist movement in New York City. Absent from the map were a number of incredibly important sites in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, which were a hotbed of abolitionist activity through the 19th century, as well as the home of the city’s largest African American community. Ahead, learn about 14 significant sites of the anti-slavery movement.

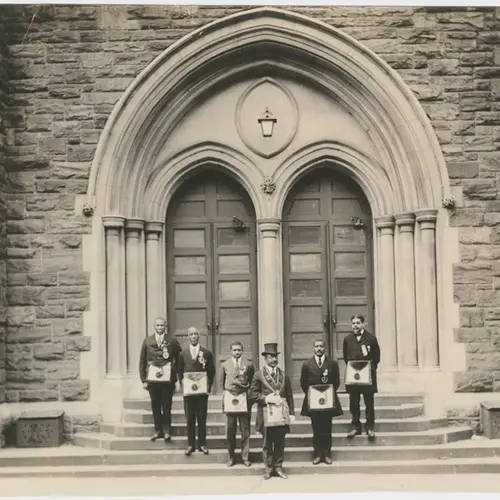

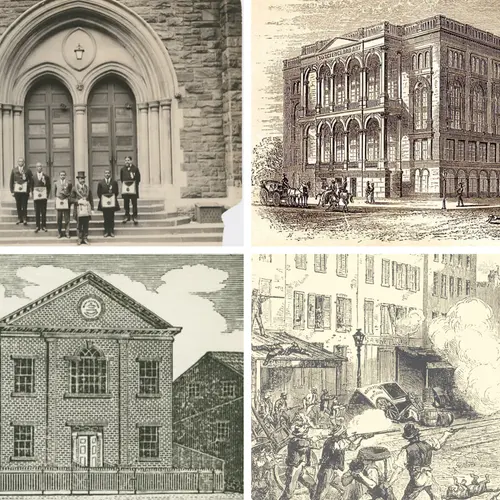

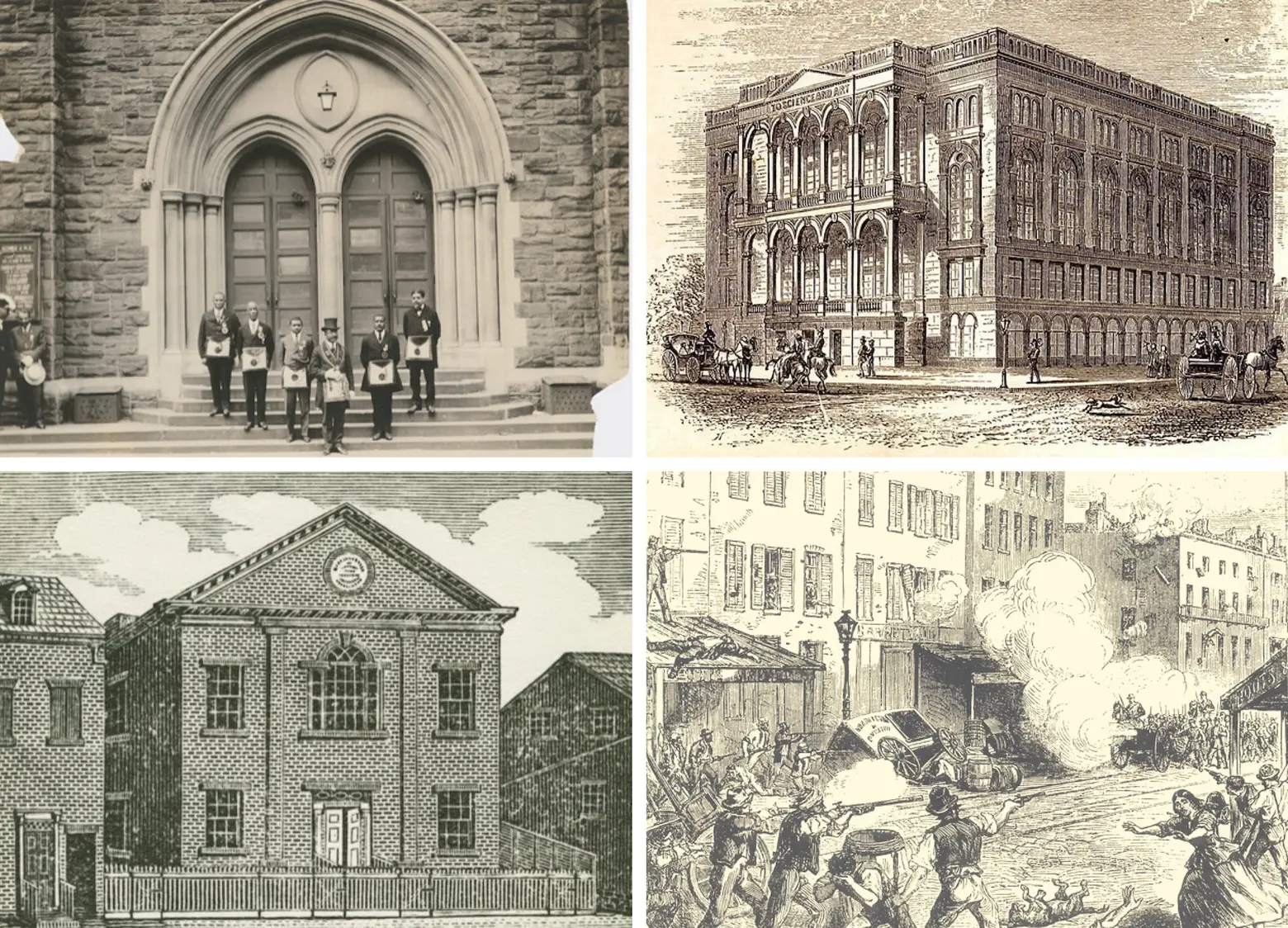

Photo courtesy of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. (1919). Arthur A. Schomburg (far right) and Harry A. Williamson (third from left) in a group portrait with fellow members of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge, on the steps of Mother A.M.E. Zion Church

As the center of New York’s African American community in the 19th century, it’s no surprise that many of the city’s most vocal anti-slavery churches were located in and around Greenwich Village. Some of these same churches are now located in Harlem, to which they moved in the 20th century, and picked up the mantle of the post-slavery civil rights struggle.

1. Mother Zion AME Church

Located at 10th and Bleecker Streets in Greenwich Village, “Freedom Church,” as it was also known, was the founding congregation of the Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church, which now has congregation across the African diaspora of North America and the Caribbean. Originally located in Lower Manhattan, it was New York’s first and only black church for decades, and a stop on the Underground Railroad. Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Frederick Douglass were all involved with Zion AME. In the early 20th century the congregation moved first to the Upper West Side and then Harlem, where it remains today. The Greenwich Village church was demolished, replaced with the tenement which stands on the site today.

Current view of 166 Waverly Place

Photo courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. (1936). The exterior of Abyssinian Baptist Church, in Harlem, New York City, May 1936.

2. Abyssinian Baptist Church, 166 Waverly Place

Formed in 1808, this congregation began when a handful of free blacks withdrew from the First Baptist Church in New York in protest against the practice of segregating blacks in what was called a “slave loft.” Some were natives of Ethiopia, then known as Abyssinia, and the founding of the church was an affirmation of their African heritage and proudly called attention to ancient Christian traditions in Abyssinia. It was also only the second black church in New York City after Mother Zion AME Church. The congregation worshiped in several places in Lower Manhattan until 1856 when it moved to Greenwich Village.

Throughout its history, Abyssinian Baptist Church advocated for an end to slavery and withstood the Draft Riots of 1863 which took place just outside its front door. One of the richest black churches in the city, by 1900 it claimed over 1,000 members. Soon thereafter many traces of Little Africa began to disappear from the area as African Americans moved to the Tenderloin between West 23rd and 42nd Streets, San Juan Hill in what is now Lincoln Square, and eventually Harlem. The church is located there today, still on the forefront of civil rights activism.

Current street view of 450 Sixth Avenue; Map data © 2019 Google

The Shiloh Presbyterian Church was renamed (to St. James Presbyterian) and relocated to Harlem in 1905; Photo by Jeff Reuben on Wikimedia

3. Shiloh Presbyterian Church, 450 Sixth Avenue

One of the most vocal and active anti-slavery churches, Shiloh was founded in Lower Manhattan in 1822 as the First Colored Presbyterian Church. Its founder Samuel Cornish also founded America’s first black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal. Shiloh was part of the Underground Railroad since its inception. The church’s second pastor was Theodore Wright, who was a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Wright’s successors were J.W.C. Pennington and Henry Highland Garnet, both vocal and high-profile fugitive slaves. Under Garnet’s leadership, the church found new ways to fight slavery, including calling for boycotts of slave products such as sugar, cotton, and rice. During the Civil War, Garnet and Shiloh aided African American victims of the deadly 1863 Draft Riots and those seeking to escape attack. Its location at 450 Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village was part of its long slow migration north, eventually ending in Harlem, where it remains today.

4. Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, 23-25 East 6th Street

This East Village church was the place of worship and destination of Elizabeth Jennings Graham (the church’s organ player) when she was forcibly ejected from a New York City streetcar in 1854 for being black. This led to a high-profile campaign to desegregate this public transport system a full century before Rosa Parks. The crusade led by Graham and her father led to significant (if not complete) reform and integration of New York City’s streetcars, with the courts finding that a sober, well-behaved person could not be removed from a streetcar solely on the basis of their race.

5. Spring Street Presbyterian Church, 246 Spring Street

Founded in 1809, Spring Street Presbyterian Church was one of the city’s most prominent and vocal abolitionist churches. The church had a multiracial Sunday school and admitted African Americans to full communion, which raised the ire of many of their neighbors. The church was burned down twice by the 1830s, including in the anti-abolitionist riots of 1834, only to be defiantly rebuilt each time. The church also had a cemetery on its grounds, where members of its multi-racial congregation were laid to rest.

The church closed in 1963 and 1966 after the building was destroyed by a fire and paved over for a parking lot, though the contents of the cemetery were never removed. In 2006 the site was purchased for the construction of the highly-controversial Trump Soho (recently rebranded as the Dominick Hotel), and in the process of doing excavation on the site for the hotel, human remains were exhumed. Rather than halting the project to respect the abolitionist church’s burial ground, the city simply allowed Trump and his partners to report that they had removed the remains to a lab in Upstate New York, where the Presbyterian Church was charged with finding a final resting place for them.

6. Henry Highland Garnet, 183 & 185 Bleecker Street, 175 MacDougal Street, 102 West 3rd Street

Henry Highland Garnet was an abolitionist, minister, educator, and orator, and the first African American to address the United States House of Representatives. Born into slavery in Maryland in 1815, in 1824 his family of 11 received permission to attend a funeral, and used the opportunity to escape slavery, eventually reaching New York City. He joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and frequently spoke at abolitionist conferences. His 1843 “Address to the Slaves,” a call to resistance made at the National Convention of Colored Men in Buffalo, brought him to the attention of abolitionist leaders across the country. Convinced that talking would never change the minds of slave owners, he was among the first to call for an uprising.

Garnet also supported the emigration of blacks to Mexico, Liberia, and the West Indies, where they would have more opportunities, as well as black nationalism in the United States. He became the leader of the Shiloh Presbyterian Church. Shiloh was part of the Underground Railroad, and under Garnet they found new ways to fight slavery, including boycotts of sugar, cotton, rice, and other goods which were the products of slave labor. Years later, when John Brown was hung for leading an armed slave uprising in Virginia, Garnet held a large memorial for him at the Shiloh Church.

On February 12, 1865, in the final weeks of the Civil War, the Rev. Dr. Henry Highland Garnet became the first African American to address the U.S. House of Representatives when he delivered a sermon commemorating the victories of the Union army and the deliverance of the nation from slavery. He had been invited by President Abraham Lincoln with the unanimous consent of his cabinet and the two congressional chaplains for a special Sunday service held on President Lincoln’s birthday. In 1881 he was appointed U.S. Minister to the black African nation of Liberia, founded by freed U.S. slaves, allowing him to achieve his dream of living in Liberia. However, he died a mere two months after his arrival there.

Via Wikimedia CC

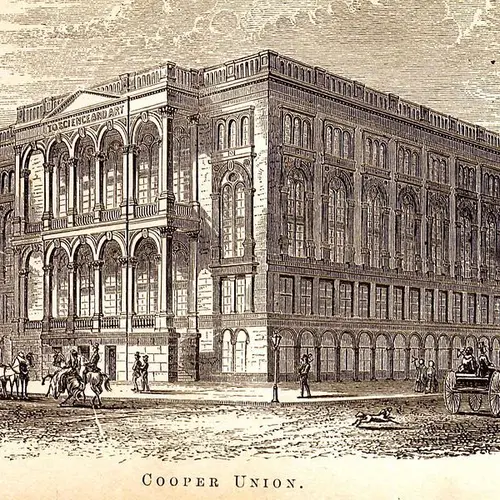

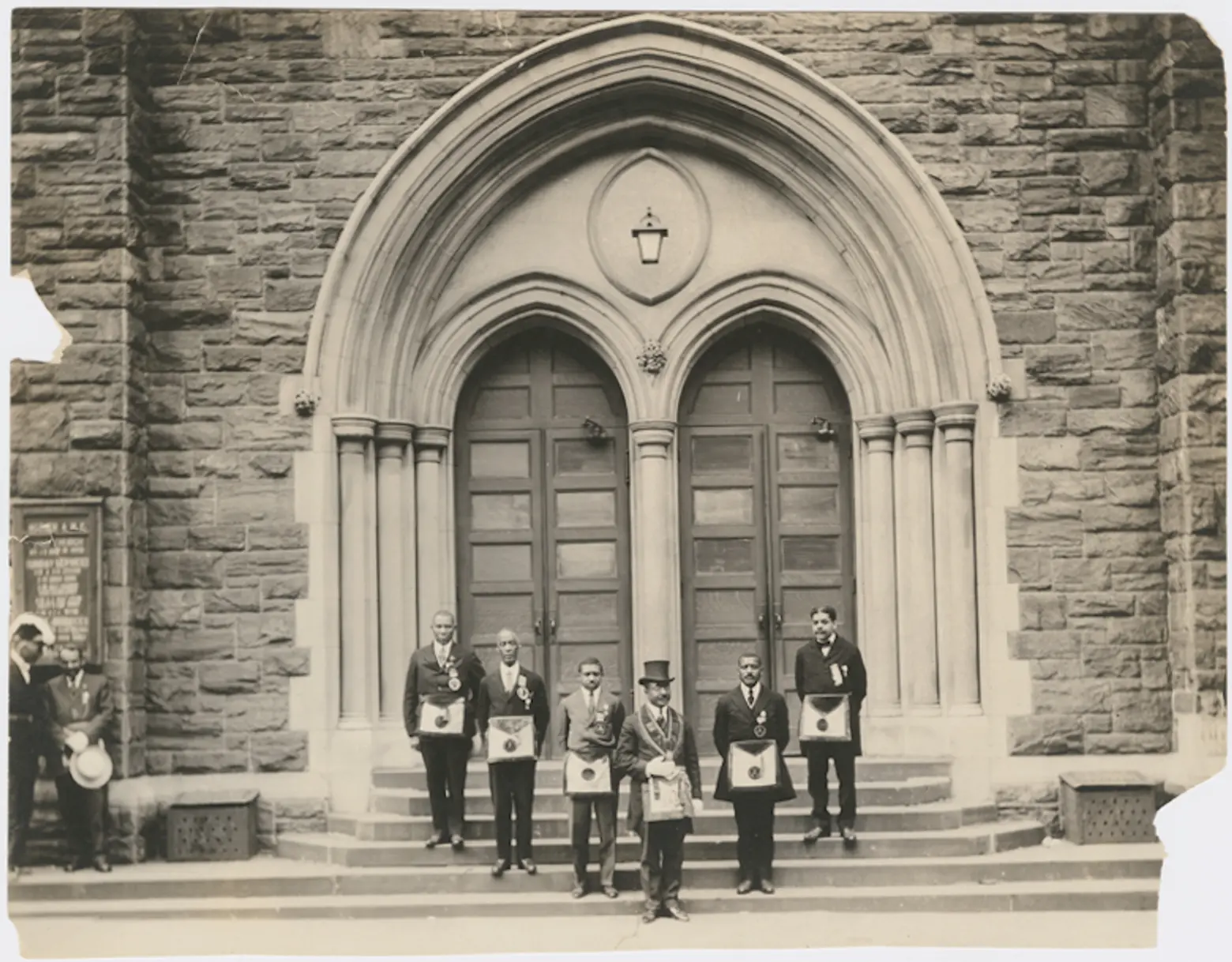

7. Cooper Union, East 7th Street between 3rd Avenue and Cooper Square

While this school was only founded in 1859, it quickly jumped into the anti-slavery fray. Founder Peter Cooper was a fervent anti-slavery advocate, and among the first speakers at the school’s Great Hall were Abraham Lincoln, whose speech here catapulted him to national prominence and the Presidency, and the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass. In the 20th century, Cooper Union’s Great Hall was also the site of the first public meeting of the NAACP.

8. One of the first free black settlements in North America

The first legally emancipated community of people of African descent in North America was found in Lower Manhattan, comprising much of present-day Greenwich Village and the South Village, and parts of the Lower East Side and East Village. This settlement consisted of individual landholdings, many of which belonged to former “company slaves” of the Dutch West India Company. These former slaves, both men and women, had been manumitted as early as within 20 years of the founding of New Amsterdam and their arrival in the colonies. In some cases, these free black settlers were among the very first Africans brought to New Amsterdam as slaves in 1626, two years after the colony’s founding. Several petitioned successfully for their freedom. They were granted parcels of land by the Council of New Amsterdam, under the condition that a portion of their farming proceeds went to the Company. Director-General William Kieft granted land to manumitted slaves under the guise of a reward for years of loyal servitude.

However, these particular parcels of land may have been granted by the Council, at least in part, because the farms lay between the settlement of New Amsterdam on the southern tip of Manhattan Island and areas controlled by Native Americans to the north. Native Americans sometimes raided or attacked the Dutch settlement, and the farms may have served as a buffer between the two. However, this area was also among the most desirable farmland in the vicinity, and the Dutch Governor Peter Amsterdam established his own farm here in 1651, offering a different potential interpretation of the choice of this area for the settlement. This settlement’s status did not remain permanent. When the English captured the colony of New Amsterdam and renamed it “New York” in 1664, the newly established English government demoted free blacks from property owners to legal aliens, denying them landowning rights and privileges. Within 20 years, a vast majority of land owned by people of African descent was seized by wealthy white landowners who turned these former free black settlements into retreats, farms, and plantations.

110 Second Avenue; Map data © 2019 Google

9. Issac T. Hopper and Abigail Hopper Gibbons House, 110 Second Avenue

Isaac T. Hopper was a Quaker abolitionist first active in the Philadelphia anti-slavery movement who notably sheltered and protected fugitive slaves and free blacks from slave kidnappers. His daughter, Abigail Hopper Gibbons, was also an ardent abolitionist, whose beliefs, along with those of her father and husband, got them disowned by even some Quaker congregations.

The elder Hopper built and lived in a house at 110 Second Avenue in the East Village. He gave it to his daughter, who in turn gave it to the Women’s Prison Association, which she led, a group aimed at reforming the prison system and helping women. She named the facility after her abolitionist father. As well-known abolitionists, both their homes were attacked by mobs during the 1863 Draft Riots. The building made the National Register of Historic Places in 1986 and was designated as a New York City landmark in 2009.

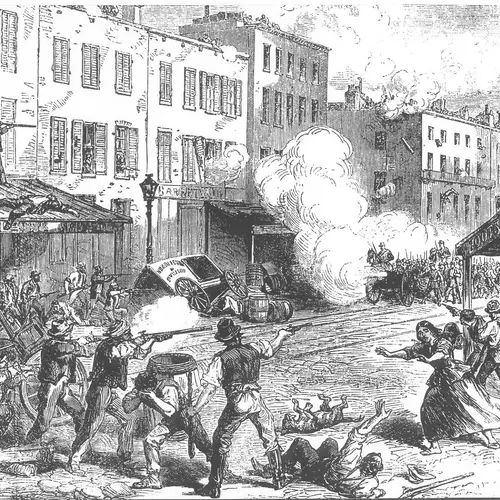

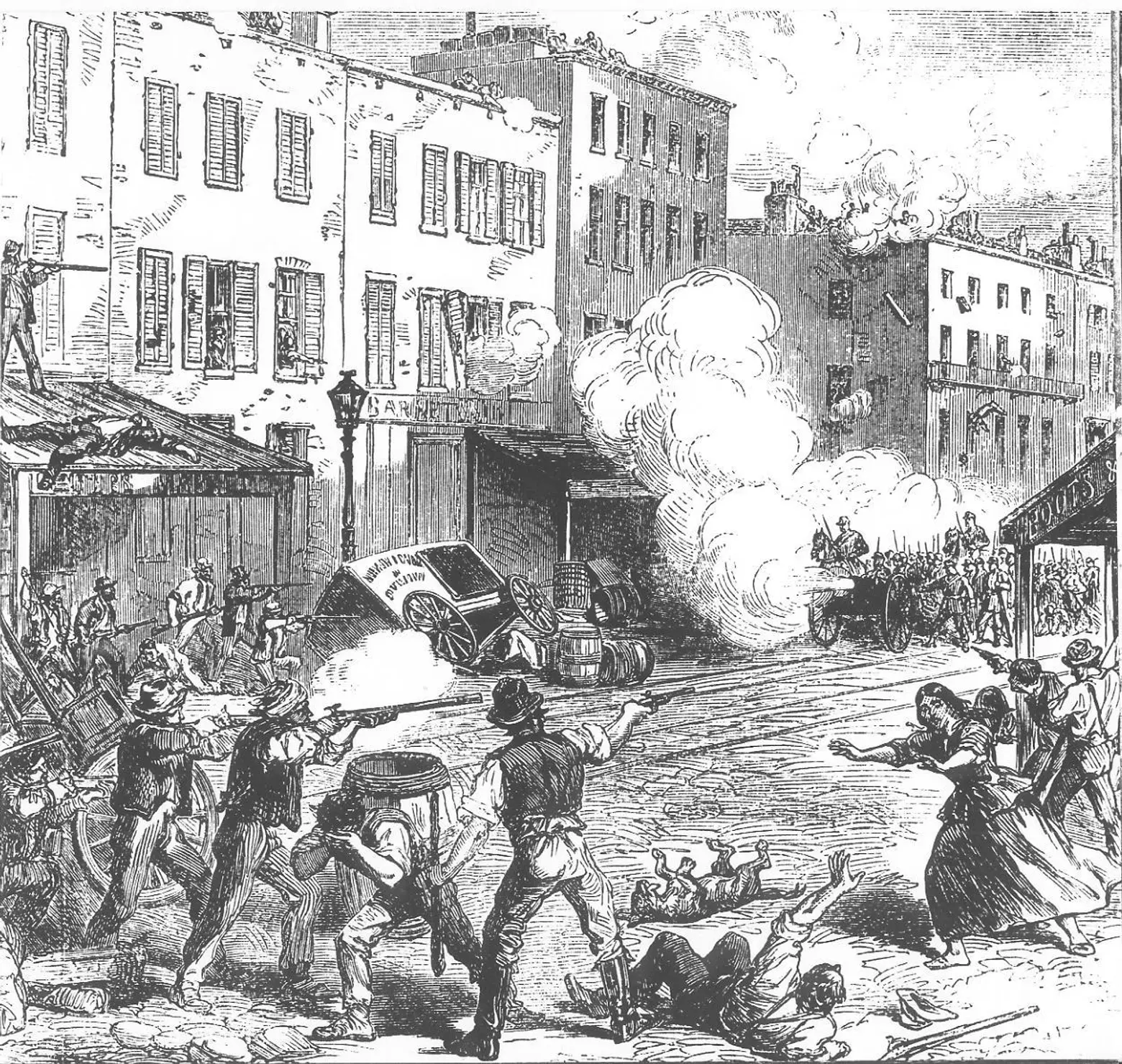

An illustration of the New York Draft Riots in 1863 via Wikimedia

10. Draft Riots Refuge, 92 Grove Street

During the deadly 1863 Draft Riots, the largest civil insurrection in American history during which hundreds of African Americans were killed and thousands more attacked, terrorized, and made homeless, the home at 92 Grove Street was known as a safe harbor for those targeted by the rampaging mobs. The owners of the home provided refuge in their basement. The house was located just on the edge of what was then known as “Little Africa,” the largest African American community in New York centered around today’s Minetta Street and Lane, and was just a few doors down the block from the Abyssinian Baptist Church, one of the largest African American churches at the time.

The house was demolished in 1916 and replaced with the apartment building which remains there today. One hundred years after the Draft Riots, writer Alex Haley lived and wrote at this same address, meeting with and interviewing Malcolm X here more than fifty times for The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

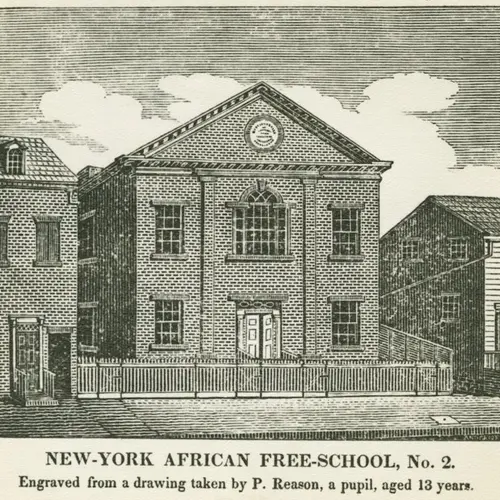

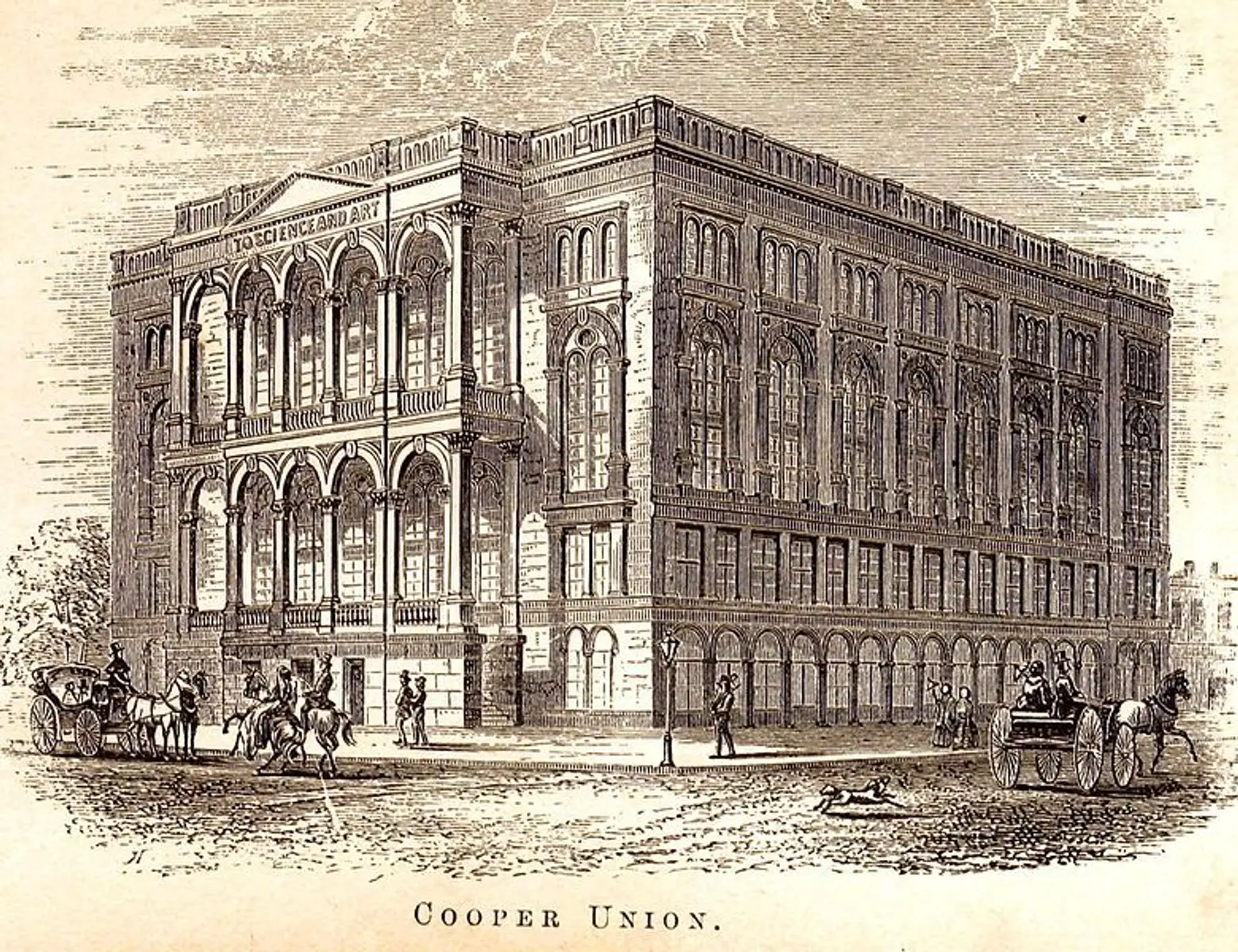

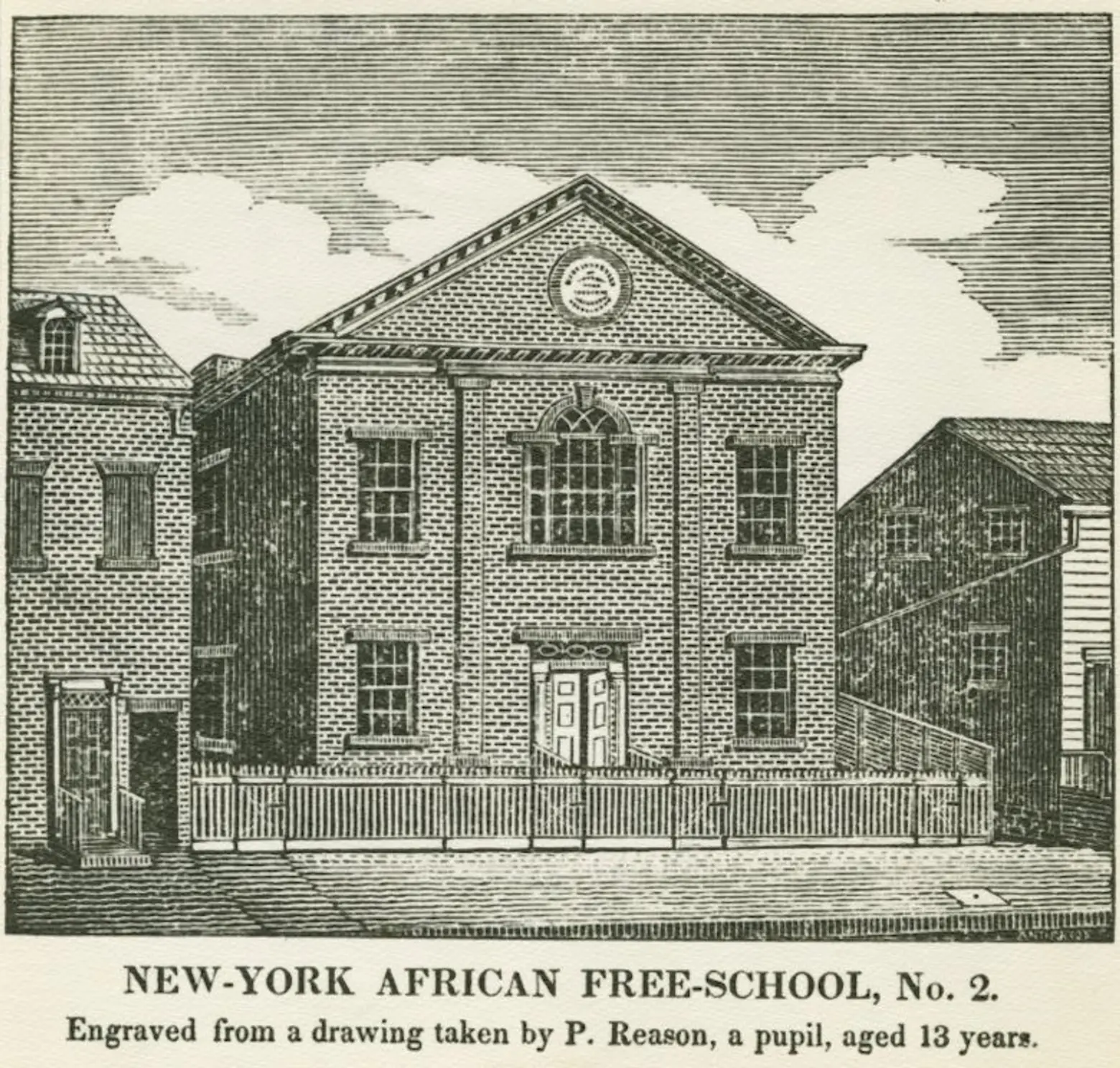

New York African Free Schoo, No. 2, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. African Free School, No. 2, New York.

11. African Free School No. 3, 120 West 3rd Street

This was one of seven schools dedicated to the education of the children of free and enslaved blacks in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The first African Free School was the very first school for blacks in America. It was founded in 1787 by members of the New York Manumission Society, an organization devoted to the full abolition of African slavery, led and founded by Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. At the time of its creation, many African residents in the city were still slaves. The mission of the institution was to empower and educate young black people, which was a complicated and bold proposition for the time.

In 1785 the Society worked to pass a New York State law prohibiting the sale of slaves imported into the state. This preceded the national law prohibiting the slave trade, passed in 1808. The 1783 New York law also lessened restrictions on the manumission of enslaved Africans. In New York, a gradual emancipation law was passed in 1799, which provided that children of enslaved mothers would be born free. However, long periods of indentured servitude were required; 28 years for men and 25 for women. Existing slaves were eventually freed until the last slaves were freed in 1827.

The first African Free School, a one-room schoolhouse located in lower Manhattan, was established in 1794 and held about 40 students. Here, the children of both free and enslaved blacks were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and geography. Boys were also taught astronomy, a skill required of seamen, and girls were taught sewing and knitting. After a fire destroyed the original building, a second school was opened in 1815 and held 500 students. African Free School No. 2, located on Mulberry Street, was Alma mater to abolitionist and educator Henry Highland Garnet. African Free School No. 3 was established on 19th Street near 6th Avenue; however, after objections from whites in the area, it was relocated to 120 Amity Street (now known as 120 West 3rd Street). By 1834 the seven existing African Free Schools, with enrollment surpassing a thousand students, had been absorbed into the public school system.

12. Home of John Jay II, 22 Washington Square North

The son of William Jay, who became president of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society in 1835, and grandson of John Jay, president of the first Congress and the first Chief Justice (as well as an abolitionist and co-founder with Alexander Hamilton of the African Free School), John Jay II became the manager of the New-York Young Men’s Anti-Slavery Society in the mid-1830s. Still studying at Columbia College, he was one of the school’s two students to participate in the group, which rejected the practice of slavery and called for immediate abolition. During the New York anti-abolitionist riots in 1834, Jay and his peers defended the home of Arthur Tappan, who then served as the president of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

In the 1840s and 50s, Jay’s work as a lawyer focused on defending fugitive slaves in New York City. Later, during the Civil War, he advised Abraham Lincoln and the president’s cabinet. Jay also spoke against the New York Episcopal diocese, particularly Bishop Benjamin T. Onderdonk, a Columbia graduate and trustee who barred black members of the institution and attendees at the annual Episcopal Convention, and who denied representation to the black congregation of St. Philip’s Church. This was at least partially due to the New York Episcopal diocese’s relationship with southern Episcopalian churches and its attempt to avoid controversies surrounding the issue of slavery. Jay’s campaign put him in direct conflict with his alma mater, Columbia, since eighty percent of the school’s trustees were Episcopalian, and many of the Church’s leaders were graduates of the school as well.

The church moved to West 53rd Street in 1898; Photo by James Russiello on Wikimedia

13. Rev. Thomas Farrell & St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, 371 Sixth Avenue

St. Joseph’s was built in 1833 and is the oldest intact Catholic Church in New York. Thomas Farrell, one of the first pastors at the predominantly Irish-American church, spent his tenure advocating for emancipation and the political rights of African Americans. In his will, Farrell wrote: “I believe that the white people of the United States have inflicted grievous wrong on the colored people of African descent, and I believe that Catholics have shamefully neglected to perform their duties toward them. I wish, then, as a white citizen of these United States and a Catholic to make what reparation I can for that wrong and that neglect.”

When he died, Farrell gave $5,000 to found a new parish for the city’s Black community, which became the nearby Church of St. Benedict the Moor at 210 Bleecker Street. This church was the first African American Catholic church in the North of the Mason-Dixon line. In 1898, as the city’s African American community migrated uptown, the church moved to 342 West 53rd Street, where it remains today. 210 Bleecker Street eventually became Our Lady of Pompeii Church; that structure was demolished in 1926 and replaced with the church by that name which stands today at Bleecker and Carmine Streets.

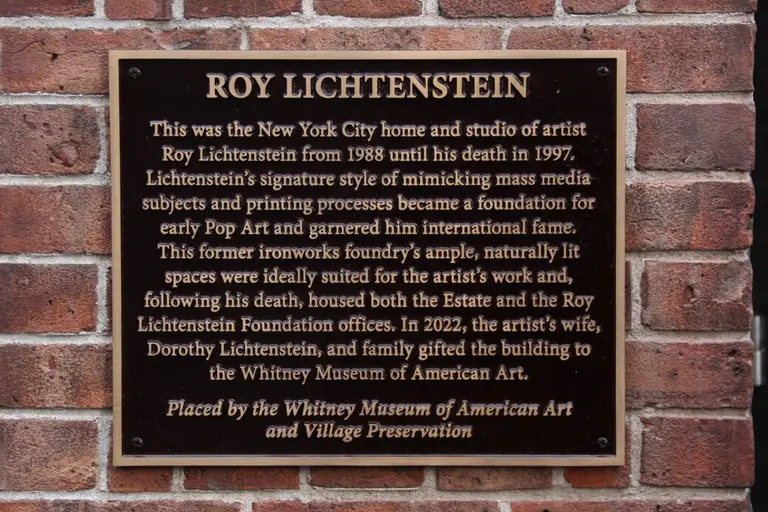

14. The Freedman’s Saving Bank, 142 & 183-185 Bleecker Street

On March 3, 1865, The Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company, commonly referred to as the Freedman’s Savings Bank, was created by the United States Congress to aid freedmen in their transition from slavery to freedom. During the bank’s existence, 37 branches were opened in 17 states and the District of Columbia. On August 13, 1866, a New York branch opened at 142 Bleecker Street (at LaGuardia Place). By October 1869, the bank had moved to a pair of row houses at 183-185 Bleecker Street (MacDougal/Sullivan Streets). All three buildings have since been demolished.

The Freedmen’s Bank was created to help freed slaves and African Americans in general. At the time, this part of Greenwich Village had a very large community of both recently-free African Americans from the South, and longtime free or free-born African Americans. Deposits at the Freedman’s Bank could only be made by or on behalf of former slaves or their descendants and received up to 7 percent interest. Unclaimed accounts were pooled together to fund education for the children of ex-slaves.

Frederick Douglass, who had been elected president of the bank in 1874, donated tens of thousands of dollars of his own money in an attempt to revive the bank, which after great initial success and after the Great Panic of 1873 was failing. Despite his efforts, the bank closed on June 29, 1874, leaving many African Americans cynical about the banking industry. Congress established a program that made depositors eligible for up to 62 percent of what they were owed, however many never received even that much. Depositors and their descendants fought for decades for the money they were owed and for the government to assume some responsibility, but they were never compensated.

RELATED:

- Find landmarks of the anti-slavery movement in NYC

- The history of Weeksville: When Crown Heights had the second-largest free black community in the U.S.

- On this day in 1645, a freed slave became the first non-Native settler to own land in Greenwich Village

+++

This post comes from Village Preservation. Since 1980, Village Preservation has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid