What lies below: NYC’s forgotten and hidden graveyards

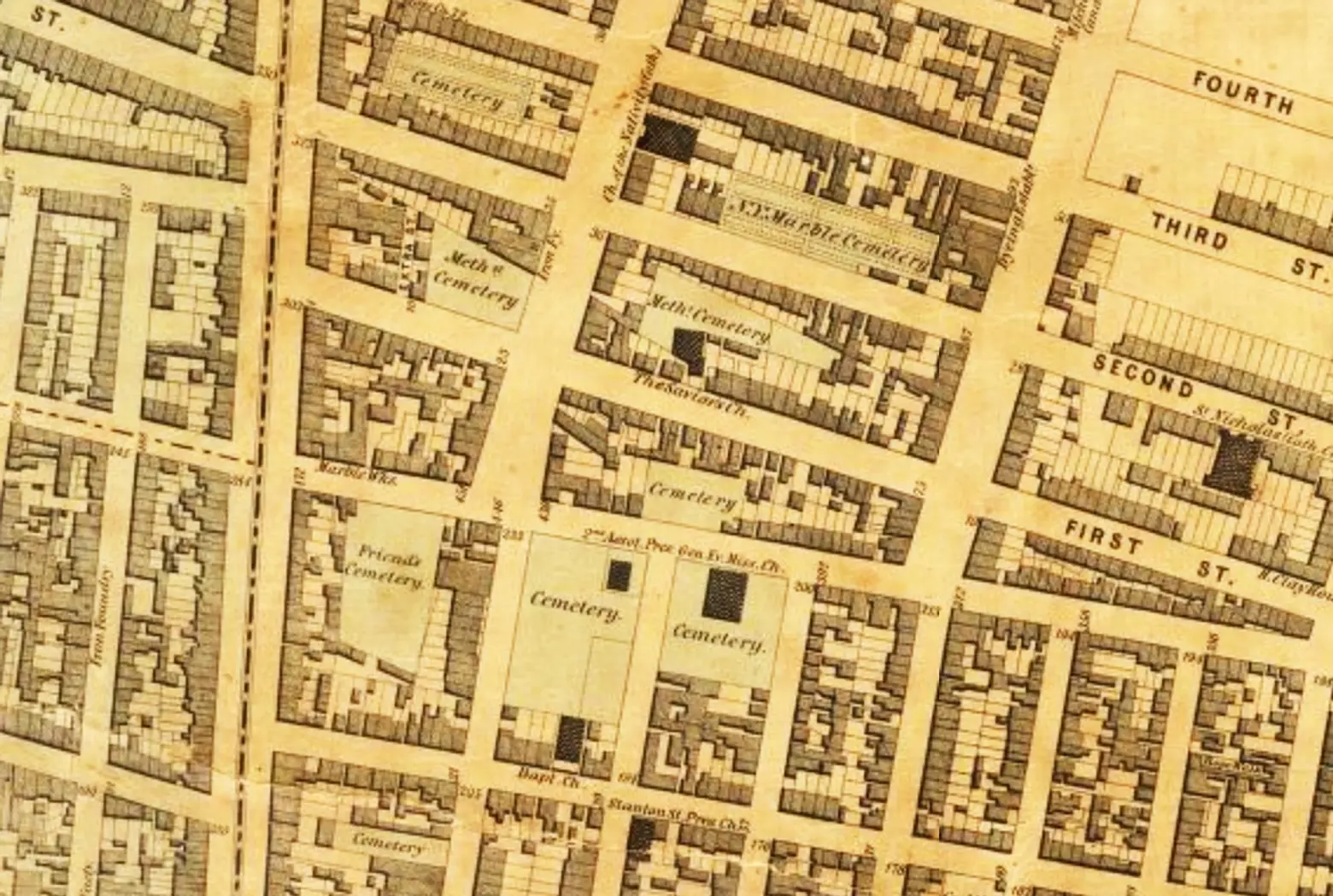

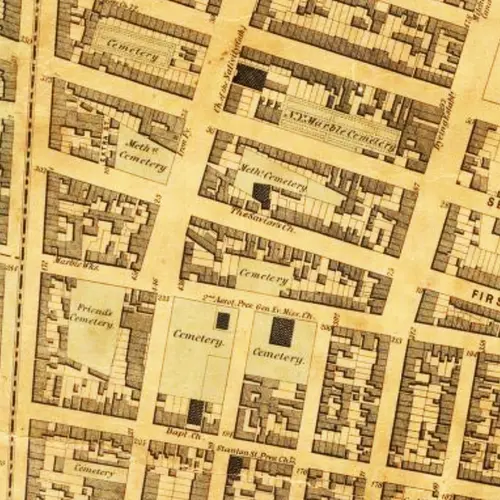

Zoom of the 1852 Dripps map of Manhattan, showing the proximity of downtown cemeteries, via David Rumsey Map Collection

Most New Yorkers spend some time underground every day as part of their daily commute, but some spend eternity beneath our streets, and in a few cases occupy some pretty surprising real estate.

Manhattan cemeteries are tougher to get into than Minetta Tavern without a reservation on a Saturday night because as far back as 1823, New York forbade new burials south of Canal Street. In 1851 that prohibition was extended to new burials south of 86th Street, and the creation of new cemeteries anywhere on the island was banned. But thousands of people were buried in Manhattan before those restrictions went into effect. And while some gravesites remain carefully maintained and hallowed ground, such as the those at St. Mark’s in the Bowery Church on Stuyvesant Street, Trinity Church on Wall Street, and St Paul’s Church at Fulton and Broadway, others have been forgotten and overlaid with some pretty surprising new uses, including playgrounds, swimming pools, luxury condos, and even a hotel named for the current occupant of the White House.

New York Marble Cemetery via Garrett Ziegler/Flickr

New York Marble Cemetery via Garrett Ziegler/Flickr

There are only 11 cemeteries remaining in all of Manhattan, and only one, the New York Marble Cemetery, has sold burial plots to the public – just two — in the recent past. The only other way to be buried in Manhattan (by choice, anyway) is to become pastor at Trinity Church on Wall Street (which entitles you to burial in their churchyard), get yourself named Cardinal of the Archdiocese of New York (which earns you an eternal resting spot below the high altar at St. Patrick’s Cathedral), or qualify under “extraordinary circumstances” for burial at Trinity Cemetery at 155th Street and Riverside Drive, as Ed Koch did in 2013.

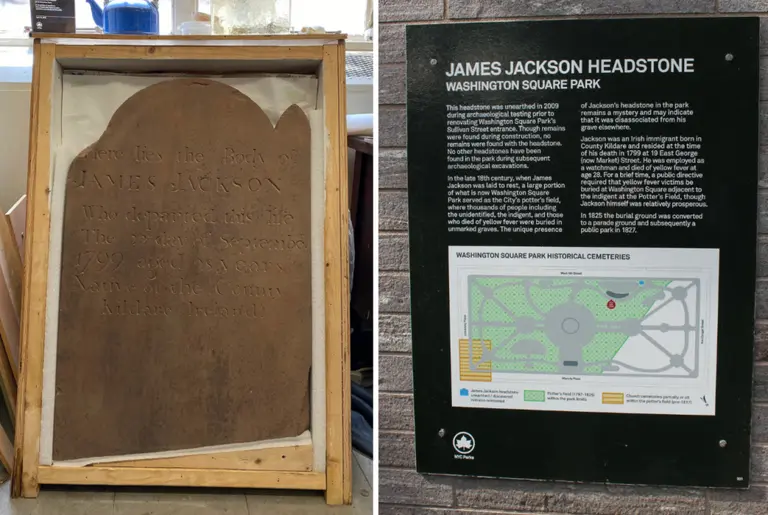

The Village and East Village, which were once country north of New York City, have more than their fair share of former burial grounds. Many New Yorkers are aware that Washington Square was originally a potter’s field, but fewer realize that some 20,000 bodies remain underneath the park, some of which were recently encountered when digging for utility repairs took place.

Less well known is that nearby JJ Walker Park between Leroy and Clarkson Streets, with its Little League fields, Recreation Center, and Keith Haring mural-ringed outdoor pool, is built over a pair of 19th-century cemeteries.

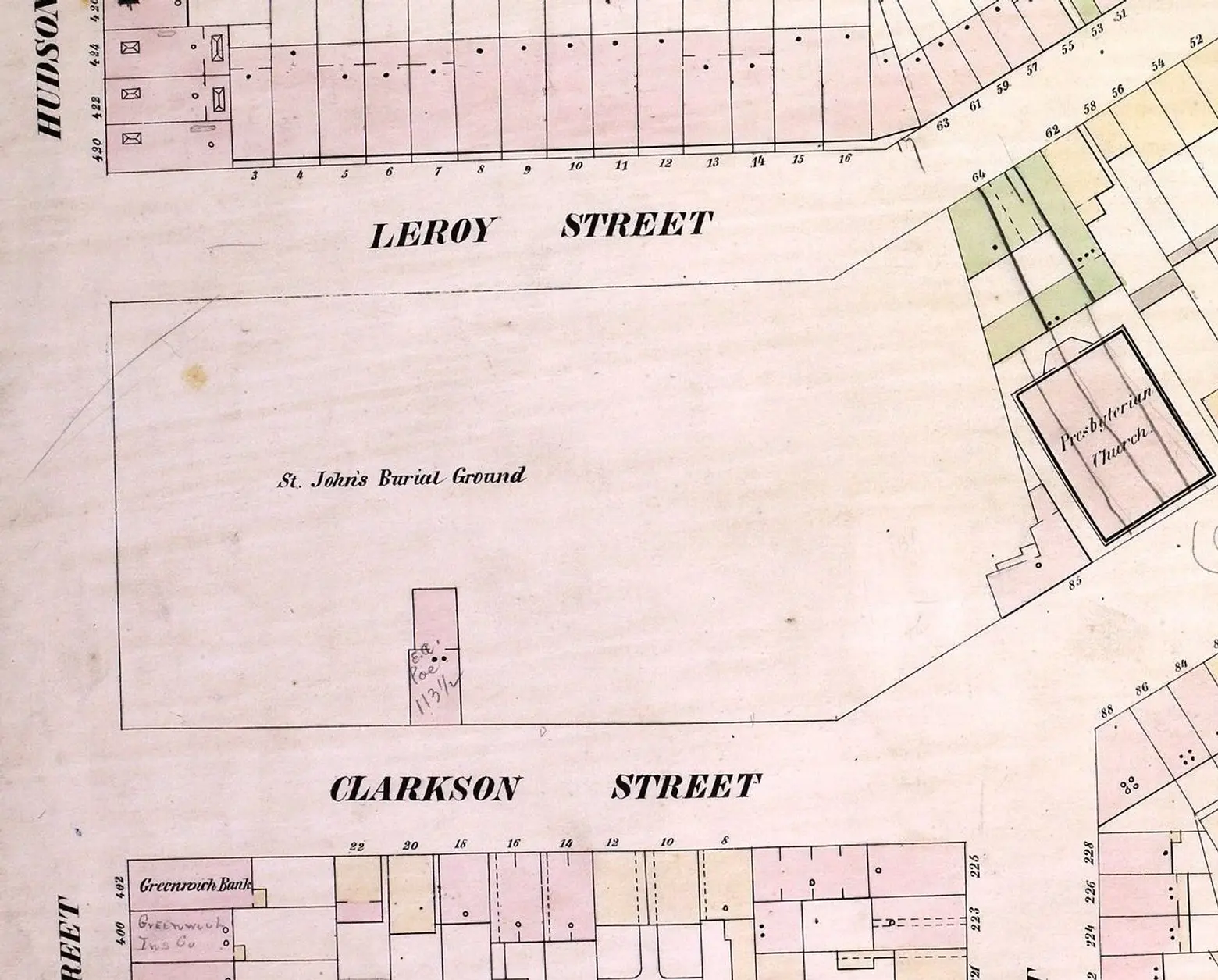

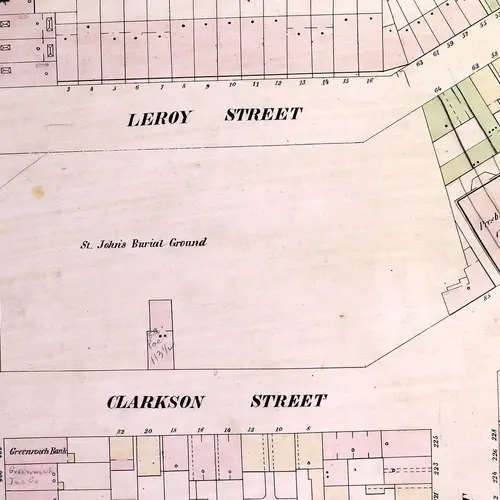

St. John’s Burial Ground in 1854, via Wiki Commons

St. John’s Burial Ground in 1854, via Wiki Commons

A Lutheran Cemetery running roughly under today’s Rec Center and pool was opened in 1809, closed in 1846, and sold in 1869, showing the rapid pace of change in this part of New York during the 1800s. The remains of 1,500 people buried there were removed and reinterred in All Faiths Cemetery in Queens. The cemetery under today’s JJ Walker playing field, belonging to Trinity Church, similarly operated from 1806 to 1852, but its final fate followed an unsettlingly different path than its Lutheran neighbor.

The park in 1899, when it was called “St. John’s Park,” via Wiki Commons

The park in 1899, when it was called “St. John’s Park,” via Wiki Commons

By 1890 Trinity Cemetery was in disrepair and based upon an 1887 act of the State Legislature which allowed the city to acquire property for the creation of small parks in crowded neighborhoods, it had been selected as the site for a new public park. But Trinity resisted the acquisition, fighting the City in court for five years. The City ultimately prevailed, and the embittered church washed their hands of responsibility for the bodies found there, saying it was now the City’s job to arrange for appropriate reinternment. The City seems to have interpreted that charge rather loosely, as they gave families of those buried one year to claim and find a new resting place for their relatives. Of the approximately 10,000 bodies buried there, mostly of middle- and lower-class New Yorkers, 250 were claimed and reinterred by their descendants. The rest remained on the site, which became a park in 1897, and those bodies remain there to this day just below the surface.

It’s one thing to learn that public parks may have once been burial grounds; more surprising may be that walk-up apartment buildings, luxury condos, and even glitzy hotels are built upon former (and in some cases present) eternal resting places.

Google Street View of John’s of 12th Street (R) and 305/310 East 12th Street (L)

Google Street View of John’s of 12th Street (R) and 305/310 East 12th Street (L)

One example can be found on 11th and 12th Streets just east of 2nd Avenue. Beginning in 1803, the land underneath much of that block served as the second cemetery to nearby St. Mark’s in the Bowery Church. The land had been donated by Peter Stuyvesant for this use with the stipulation that any of his present or former slaves and their children had the right to be buried there free of charge. Burials continued until 1851; in 1864 the land was sold and the human remains were reinterred at Evergreen Cemetery in Brooklyn. Just under a dozen tenements were built on the site of the cemetery in 1867, all but one of which were conjoined around 1940 into the single Art Deco-styled apartment complex found today at 305 East 11th/310 East 12th Street. 302 East 12th Street, where the venerable John’s of 12th Street Italian Restaurant has been located for over a century, is the sole intact survivor of that original group of cemetery-replacing tenements, and shows what the original components of the sprawling and strangely-shaped Art Deco apartment complex next door looked like before it got its 1940 makeover.

Ariel view of 305 East 11th/310 East 12th Street and 302 East 12th Street, showing the strange shape that reflects the cemetery along Stuyvesant Street previously located on this site. Via google maps.

Ariel view of 305 East 11th/310 East 12th Street and 302 East 12th Street, showing the strange shape that reflects the cemetery along Stuyvesant Street previously located on this site. Via google maps.

The unusual shape of the cemetery, and of 305 East 11th/310 East 12th Street, resulted from the prior existence of Stuyvesant Street on the site, which the cemetery originally faced (much as St. Mark’s Church still does today). While the street now runs just one block from 2nd to 3rd Avenues between 9th and 10th Streets, it originally stretched all the way from Astor Place to 14th Street, as far east as present-day Avenue A. The odd boundary of the apartment building built on the former cemetery site, which can still be seen from above today, reflects the path originally taken by Stuyvesant Street, Manhattan’s only geographically true East-West Street, which ran in front of Peter Stuyvesant’s farm (or Bowery, in Dutch).

Rendering of the Steiner East Village via Williams New York

Rendering of the Steiner East Village via Williams New York

Building upon burial grounds in Manhattan is not a phenomenon solely limited to the 19th century, however. This year, luxury condo development the Steiner East Village rose at 438 East 12th Street and Avenue A on a site where thousands of human remains once laid, and where many may still be found.

Nearly the entire block upon which that development is located, between 1st Avenue and Avenue A and 11th and 12th Streets, was from 1833 to 1848 home to the city’s third and largest Catholic cemetery, with 41,000 internments during this time. By 1883, the archdiocese sought to sell off the land, but opposition and legal challenges prevented that from happening until 1909 when the church began the process of removing and reinterring 3-5,000 individuals at Calvary Cemetery in Queens. No one knows what happened to the remains of the other 36,000+ people buried on this site, but the most logical (and not unprecedented) possibility is that like at JJ Walker Field and Washington Square–they remained on the site.

Mary Help of Christians before it was demolished, via Wiki Commons

Mary Help of Christians before it was demolished, via Wiki Commons

A church, Mary Help of Christians, a school, P.S. 60, and a bus depot were built over the former cemetery in the early 20th century. The school remains; the bus depot was demolished around 1960, replaced by today’s Open Road Park, and Mary Help of Christians Church and its school and rectory were demolished in 2014 to make way for The Steiner.

Photo of the 1867 wall via GVSHP

Photo of the 1867 wall via GVSHP

No archeological dig or other survey was ever done to see if any human remains remained on the site. What appears to be the cemetery’s 1867 wall is still visible at the western end of the site, along Open Road Park – the one faint reminder that tens of thousands of human beings were once placed here in what was supposed to be their final resting place.

Perhaps the most surprising and notorious stop on our hidden burial ground tour is the Trump Soho on Spring Street. This 40+ story glass protrusion was built on the site of a long forgotten radical abolitionist church and its burial ground – a burial ground which, along with its human remains, was still in place beneath the surface here when digging began for Trump’s eponymous and controversial development. The first Spring Street Church was built on this site in 1811 and immediately gained note for its radical integrationist practices. Even after emancipation in New York in 1827, its activities generated fear and loathing in some quarters of the city, so much so that in 1834 violent mobs attacked and sacked the church and the nearby homes of its reverend. The church rebuilt on the site in 1836, and that edifice stood until 1966 when a fire ripped through the structure after it has been closed and abandoned for three years. The church building was razed and asphalted over for a parking lot. No one at the time seemed to recall, or care, that the church’s 19th-century burial ground also remained on the site, just below the surface.

And no one might have remembered until Trump and his partners began digging on the site to make way for their planned development and exhumed human remains. Work was stopped, but rather than forcing the rethinking of the project, Trump and co. were merely told to find an appropriate new home for the bodies. The remains were moved off-site to a lab in Upstate New York for analysis. Only through the diligent efforts of Greenwich Village’s First Presbyterian Church, the closest successor to the Spring Street Presbyterian Church were the remains finally given a new home in Greenwood Cemetery in 2014, eight years later.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED:

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

There are still people around who remember that ‘All Faiths Cemetary was ‘Lutheran Cemetary’ created from farmland sold by German farmers to provide grave sites for Lutherans.

If memory serves, there was a scene of police chasing a criminal on the Lower East Side in the movie The Naked City 1948. It shows police running through backyards behind tenement buildings. Old grave markers can be briefly seen.