The highlife: Architecture, spectacle and Art Deco New York

Photo of the 1931 Beaux Arts Ball courtesy of the Van Alen Institute

The architects who built the Jazz Age really knew how to get down. In January 1931, they turned the city’s annual Beaux Arts Ball into the ultimate Gatsby-approved bash. Instead of the stuffy historicism of years past, the party’s theme was “Fête Moderne — a Fantasie in Flame and Silver.” Advance advertising for the Ball in the New York Times promised an event “modernistic, futuristic, cubistic, altruistic, mystic, architistic and feministic,” featuring the city’s most renowned architects dressed as their buildings, celebrating both themselves and the modern fantasy metropolis they had forged in flame and silver. Art Deco New York: the skyscraper city, glittering and strong, reaching ever higher – through technological advancement and American ingenuity – toward excitement, prosperity, enlightenment, and power.

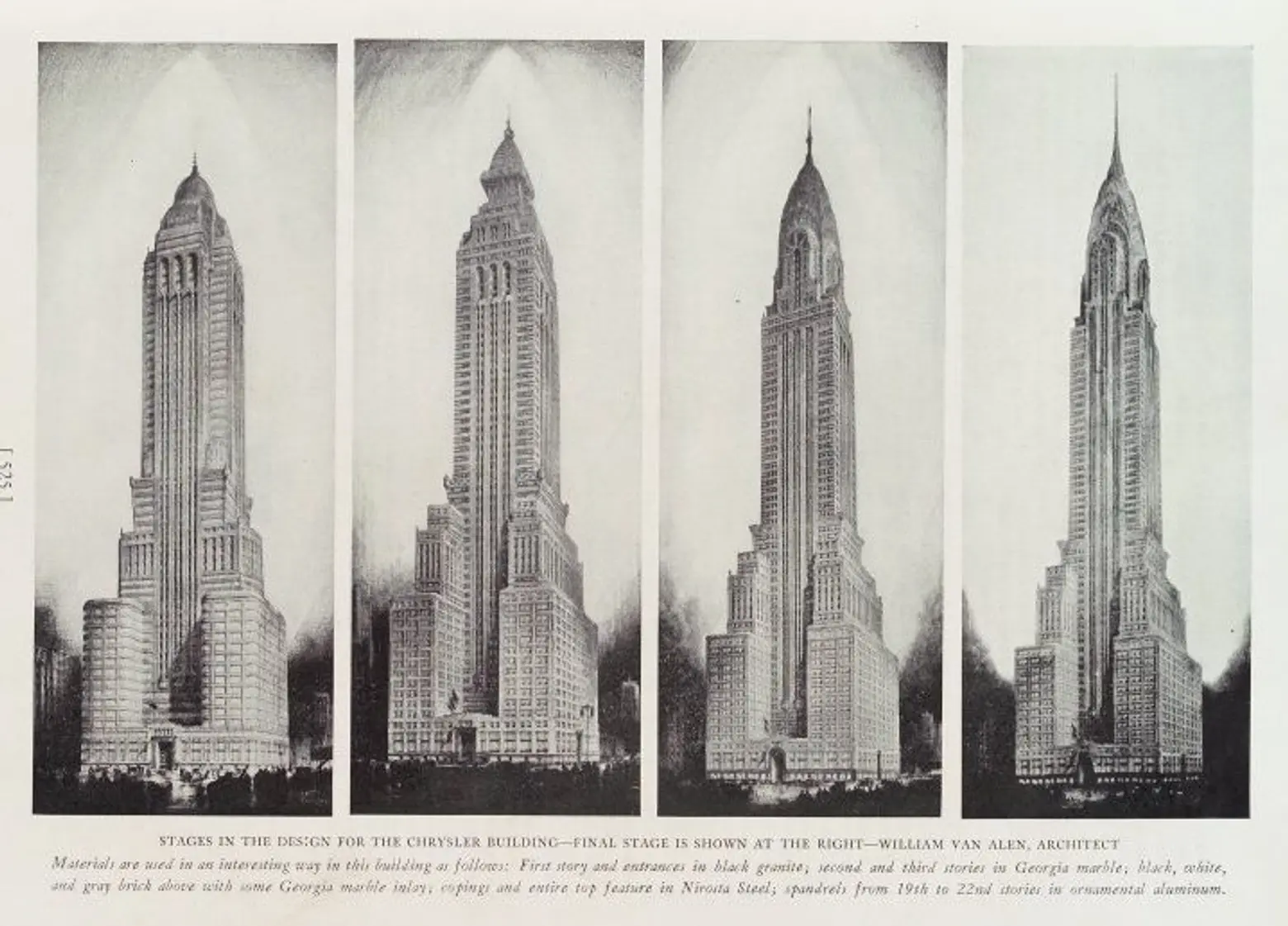

And so, the fabulous photo: William Van Alen, resplendent as his Chrysler Building, flanked from left to right by Stewart Walker (The Fuller Building), Leonard Schultze (The Waldorf-Astoria), Ely Jacques Kahn (The Squibb Building), Ralph Walker (1 Wall Street), D.E.Ward (The Metropolitan Tower), and Joseph H. Freelander (The Museum of New York). The New York Times called this lineup, “a tableau vivant of the New York Skyline.” It is clearly not a serious photograph; it’s ebullient and celebratory because vivacious living was what Art Deco was all about: taking in a show at Radio City; shopping at Bloomingdales; dancing at the Rainbow Room. Lit up, steel-coated, and wrapped in mural and mosaic – here was New York, ascendant, turned out in all its finery.

Art Deco rendered the city spectacular because it exalted in modernity and the promise of the ever-replenishing future. Reveling in the new technology that allowed the first night-lighting for buildings, the English poet Alfred Noyes wrote of New York’s skyscrapers in 1926, “by night among their vast shafts of light and shadow, you see them towering up to crown themselves with stars. You seem to discover at last new dimensions at which some of the Cubists were aiming.” The Art Deco Style translated into the built environment the principles of Modern Art and more importantly brought that artistry to the public. Here was modern, machine-driven, social luxury on an unprecedented scale.

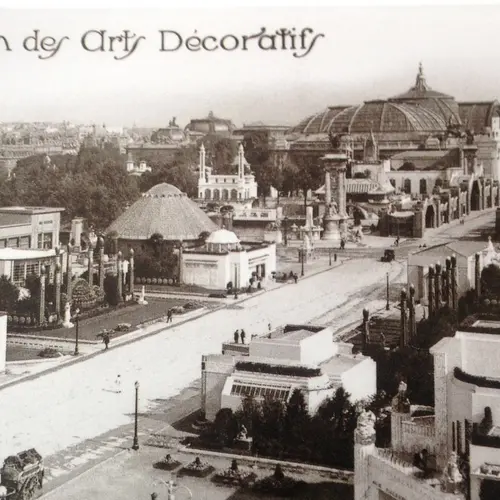

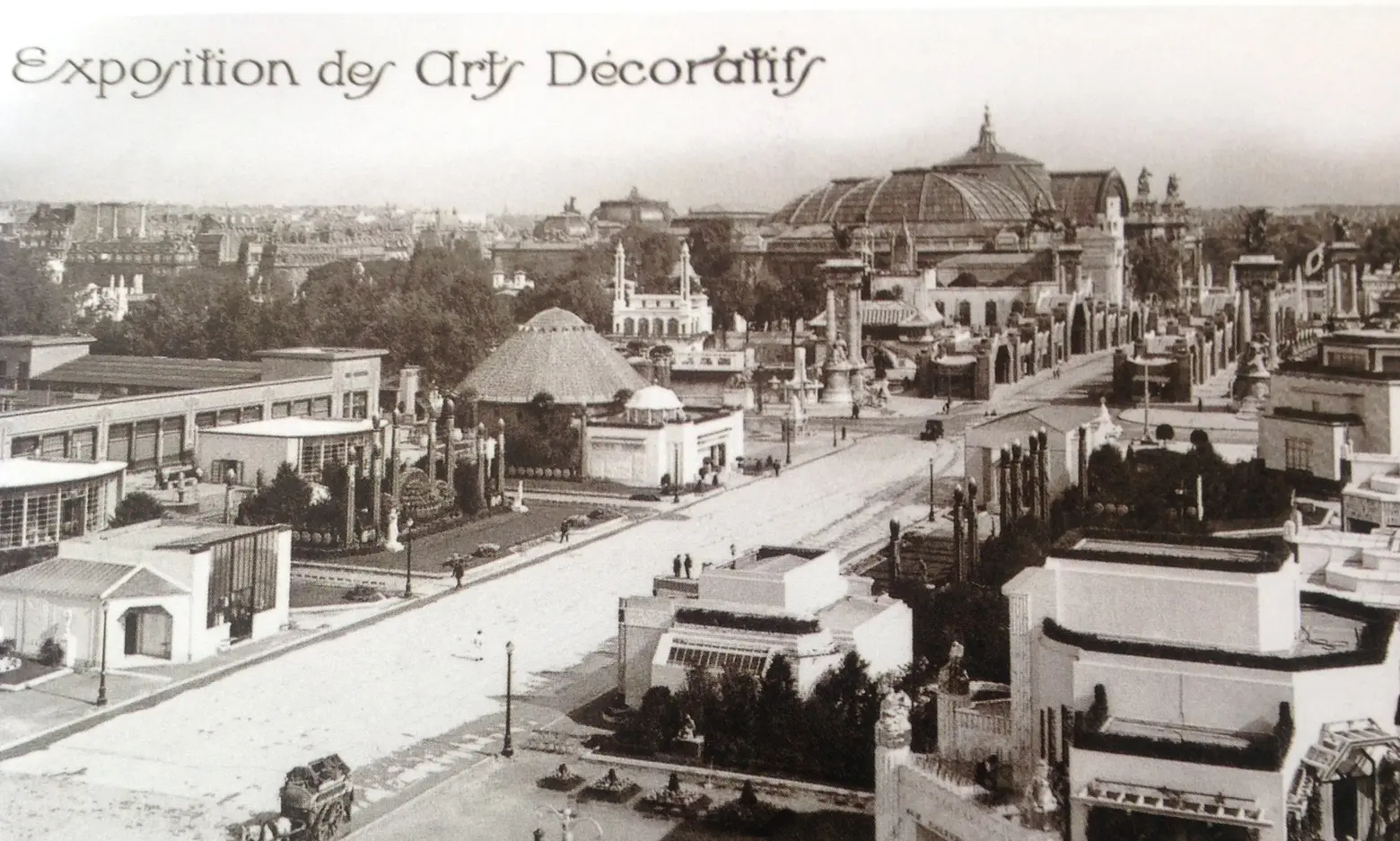

A 1925 postcard of the Exposition Internationale des Arts decoratifs et industriels modernes, via Wiki Commons

A 1925 postcard of the Exposition Internationale des Arts decoratifs et industriels modernes, via Wiki Commons

Since Art Deco was a modern style, it might seem contradictory that Art Deco architects would be gathered at the Beaux-Arts Ball, but most of them had been trained at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris, the city where Art Deco originated. In the 1920s and ‘30s, the style was known variously as “Moderne,” “Modernistic” or “Jazz Modern.” The term “Art Deco” was developed by art and architecture historians in the 1960s to refer to work exhibited at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriel Modernes in Paris in 1925.

Works included in that exhibition were simply required to show “originality and new inspiration.” As a result, an eclectic patchwork of influences – including Futurism, Cubism, Expressionism, French Art Nouveau, Austrian Secession, and German Expressionism as well as Aztec, Mayan and African Art – informed the Art Deco style, a mélange of “popular modernism” which can most simply be categorized in architecture and design as sleek, simplified forms, rich ornamentation and dramatic presentation in praise of art, industry, science, workers and commerce.

This new French Modernism immediately influenced American architects. Referring to William Van Alen in particular, the architect and critic Kenneth Murchison, described the attitudes of American architects returned from France: “No old stuff for me! No bestial copyings of arches and colyums and cornishes! Me, I’m new! Avanti!” When we consider the architect and designer Paul T. Frankl’s point that “Style is an external expression of the inner spirit of the time,” it’s easy to see why New York City became the Modern Metropolis. Post-WWI New York had the spirit, and conditions, that allowed the Art Deco Style to flourish.

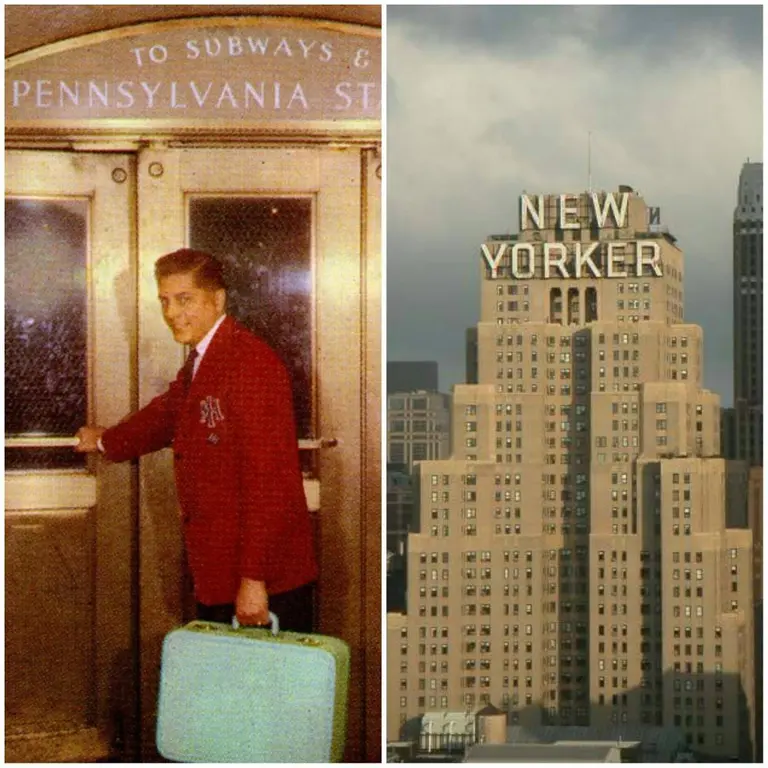

Gotham emerged from the First World War as a global city, and a center of cultural, technological and economic primacy. Even before the war was over, more goods were flowing in and out of New York harbor than anywhere else in the world and more people were engaged in printing and publishing in New York City than in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston combined. Spurred on by a surging economy, an exploding population and the benefits of exciting new technology, New York was ready to establish itself on the world stage as what H.L Mencken called “the Mecca and model for the

continent.” The city needed an identity all its own, recognizable and enviable around the world. Art Deco fit the bill perfectly.

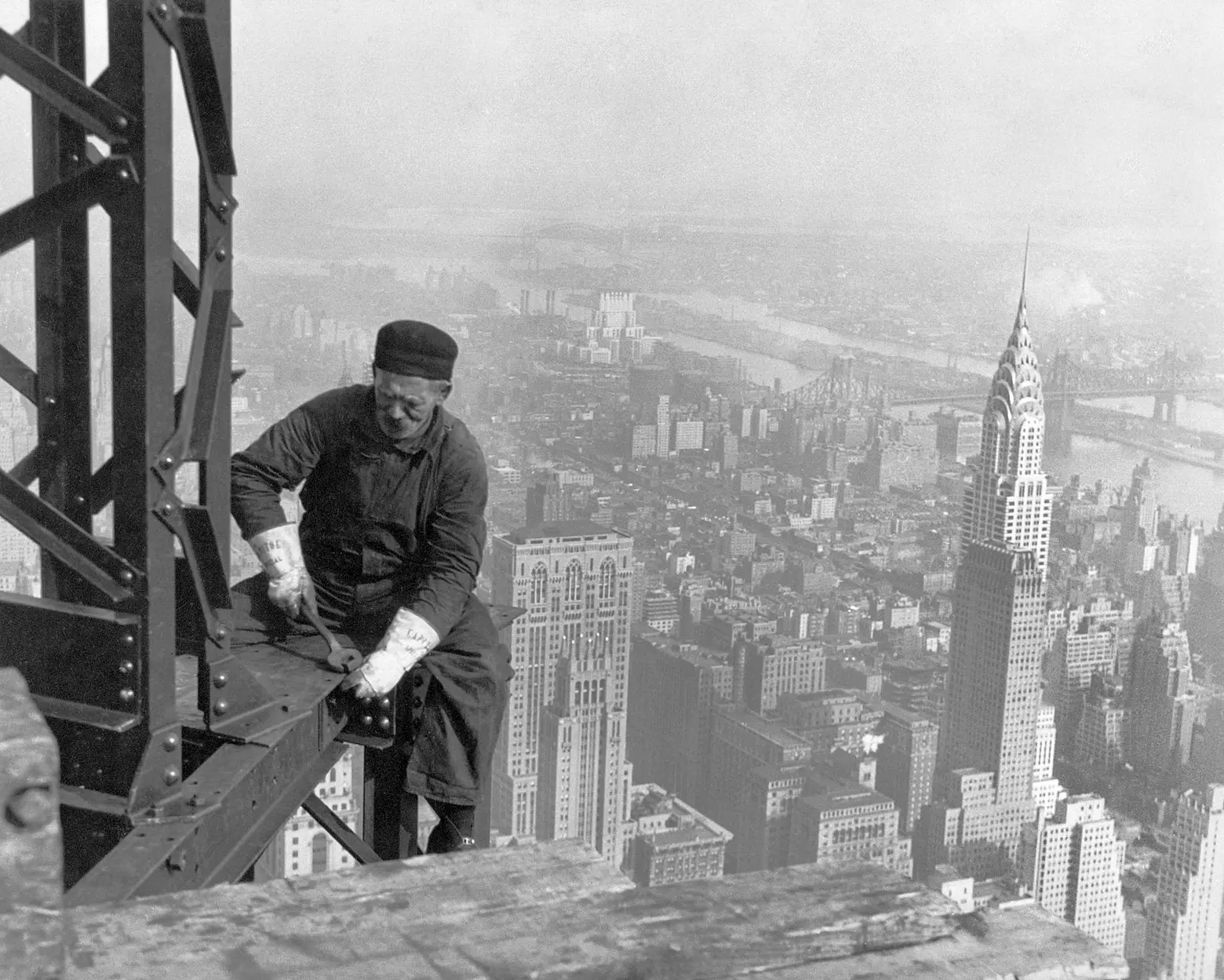

1930 photograph of a workman on the framework of the Empire State Building, via Wiki Commons

1930 photograph of a workman on the framework of the Empire State Building, via Wiki Commons

With its steel strength, sky-high ambition and glittering optimism, Art Deco became New York’s signature, creating a public face for the city. The skyscrapers that defined the skyline were advertisements for modern urban life. In fact, Colonel W.A. Starrett, of Starrett Brothers and Eken, the firm responsible for the Empire State Building, called these skyscrapers “the mountains of Manhattan…the accepted badge of cityhood.” Made inimitable by its epic, gleaming spires, wrote Fredrick V. Carpenter in 1927, New York held “something prophetic of modernity, of immense mechanical superiority, of intolerance of all that is not the newest, the latest and the best.”

What’s more “New York” than intolerance of anything short of perfection?

Perhaps the frenetic hustle of the self-made city. A self-conscious and meticulously planned ideal was inherently part of the making of Art Deco New York. The city owed as much to the path-breaking strides of Modern artists as it did to the particular vision of New York’s urban planners. In fact, New York’s 1916 Zoning Resolution, the nation’s very first city-wide zoning code, was so integral to the development of the iconic tiered structure of Art Deco architecture that the architect Ely Jacques Khan said, “the New York laws protecting property rights, light and air have encouraged a new art, by reason of the very restrictions they contain.”

Perhaps the frenetic hustle of the self-made city. A self-conscious and meticulously planned ideal was inherently part of the making of Art Deco New York. The city owed as much to the path-breaking strides of Modern artists as it did to the particular vision of New York’s urban planners. In fact, New York’s 1916 Zoning Resolution, the nation’s very first city-wide zoning code, was so integral to the development of the iconic tiered structure of Art Deco architecture that the architect Ely Jacques Khan said, “the New York laws protecting property rights, light and air have encouraged a new art, by reason of the very restrictions they contain.”

The New York Times called those restrictions “the most important step in the development of New York City since the construction of the subway.” Manhattan Borough President, George McAneny, wrote as early as 1913 that regulations were necessary “to arrest the seriously increasing evil of the shutting off of light and air from other buildings and from the public streets, to prevent unwholesome and dangerous congestion both in living conditions and in street and transit traffic, and to reduce the hazards of fire and peril to life.” Following the development of the Equitable Building, a behemoth at 120 Broadway, those restrictions were codified in the 1916 Zoning Resolution.

The Midtown skyline in 1932, showing the setbacks that resulted from the 1916 Zoning Resolution, via Library of Congress / Wiki Commons

The Midtown skyline in 1932, showing the setbacks that resulted from the 1916 Zoning Resolution, via Library of Congress / Wiki Commons

The Times reported that the Resolution, “does not prevent the building of skyscrapers, but requires that they shall not be solidly constructed for a height more than two and a half times the width of the street on which they front. For instance, if this law had been in existence…The Equitable Building could have been reared in its present proportions only to the height of 200 feet, or about eighteen stories. On top of that, a tower or series of towers could have been erected, the floor space diminishing in proportion to the increase in height.” Accordingly, some of the city’s most recognizable icons, including the Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and the GE Building (30 Rockefeller Plaza) were conceived in direct response to the particulars of this zoning ordinance.

The 1916 zoning codes were both civic-minded and financially expedient, protecting light and air, and regulating density, while also allowing the skyward growth of industry and commercial enterprise. It is no accident that the Art Deco style was most frequently utilized in commercial buildings, particularly office towers, stores and cinemas: the ‘20s typified an era devoted to “commerce and convenience,” when private enterprise replaced municipal projects as the emblems of civic pride.

In the interwar years, when the corporation replaced the small business as the primary mode of economic organization, the built environment followed suit: the corporate skyscraper became the engine of the urban ideal. For the first time, corporate architecture functioned not only as an advertisement for the corporation it housed but also as a standard of idealism to which the entire city could aspire.

No building project realized Corporate Idealism more fully than Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller Center was the largest private enterprise undertaken by an individual in American history, and the complex melded private office space with public amenities more beautifully and more successfully than any other building project in the world, exemplifying the virtues of “privately owned public space.” As a social nucleus for the city, the plaza served not only individual but also the community as a whole. So taken with the beauty and civic virtue of Rockefeller Center, Meredith Wilson, general musical director of the Western division of NBC said in 1935, “to me the plaza typifies the courage, the vision and the art of the American builder. Who but an American would think of devoting the however-many- dollars-per- front-foot, involved of that piece of the world’s most expensive real estate, to a plaza?”

No building project realized Corporate Idealism more fully than Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller Center was the largest private enterprise undertaken by an individual in American history, and the complex melded private office space with public amenities more beautifully and more successfully than any other building project in the world, exemplifying the virtues of “privately owned public space.” As a social nucleus for the city, the plaza served not only individual but also the community as a whole. So taken with the beauty and civic virtue of Rockefeller Center, Meredith Wilson, general musical director of the Western division of NBC said in 1935, “to me the plaza typifies the courage, the vision and the art of the American builder. Who but an American would think of devoting the however-many- dollars-per- front-foot, involved of that piece of the world’s most expensive real estate, to a plaza?”

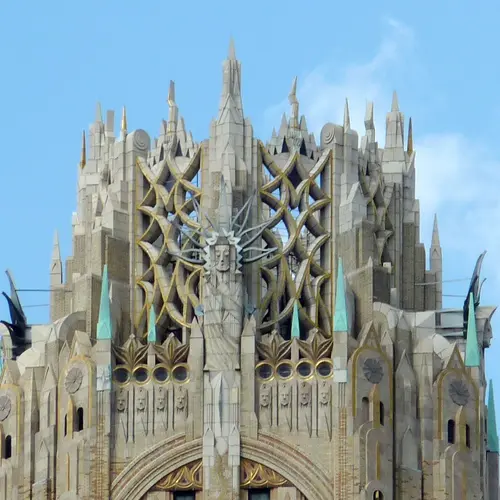

Crown of the GE Building, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, via Wiki Commons

Crown of the GE Building, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, via Wiki Commons

The NYC landmarks commission also commented on Rockefeller Center’s unparalleled corporate civicism in its 1985 landmark designation report, noting that the complex “dealt pragmatically with commerce, real estate, and urban density, and realized in almost visionary terms, the ideal of the modern, skyscraper metropolis. The complex was remarkably progressive for its pedestrian and vehicular traffic systems, unprecedented in its amenities for human enjoyment in a commercial development and unparalleled for its integration of all the arts from architecture, sculpture, mosaics, and painting to multi-level landscaping.” Conceived as “a city within a city,” the complex was planned as one entity; its buildings achieved aesthetic cohesion through shared massing, materials, ornamentation and art.

Lee Lawrie’s “Wisdom” above 30 Rockefeller Center, via Jaime Ardiles-Arce / Wiki Commons

The Center’s art program took the notion or corporate urban idealism to spectacular visual heights. The main theme of all the decorative arts in the complex is “New Frontiers.” The four sub-themes are: “man’s progress toward civilization,” “man’s development in mind and spirit,” “man’s development in physical and scientific areas,” and “man’s development of industry and the character of the nation.” Rockefeller Center perfectly encapsulated the Art Deco ideal: the city as art form.

In fact, Radio City Music Hall was christened “The Showplace of the Nation,” offering a variation on a theme: the city as theater. Frank Lloyd Wright, who decried the skyscraper, even admitted to the city’s theatrical appeal, writing, “the buildings are a shimmering verticality, a gossamer veil, a festive scene-drop, hanging there against the black sky to dazzle, entertain and amaze.”

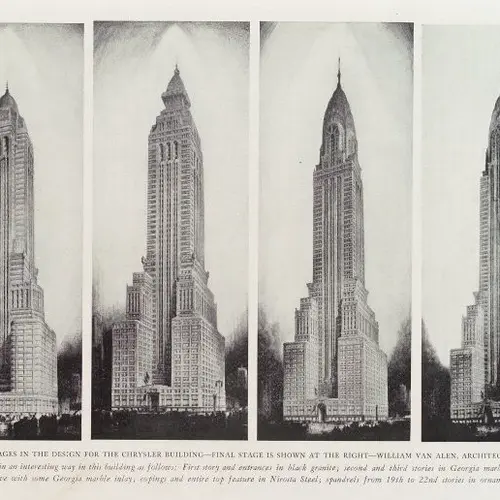

Stages of design for William Van Alen’s Chrysler Building, via NYPL / Wiki Commons

Stages of design for William Van Alen’s Chrysler Building, via NYPL / Wiki Commons

New York’s Regional Plan further cemented the notion of the city as modern theater. Completed in 1931, the Regional Plan conceived of New York as a super-city growing ever larger to contain the multitudes. It relied on decentralization to deal with urban density, anticipating the suburban sprawl made possible by the advent of the automobile. In fact, as New York’s density diminished and its population moved to the outer boroughs and the suburbs, the Art Deco theatrical ideal grew even greater. With neighborhood life moving away from the urban core, greater swaths of Manhattan could be devoted to the performance of corporate-civic dream. F. Scott Fitzgerald perfectly articulates that fantasy in The Great Gatsby, writing “the city seen from the Queensboro Bridge is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and beauty in the world.” What’s important here is not only the exultant, wild beauty of the Jazz Age city but also the fact that this is the impression one gets from afar, coming over the bridge, in from out of town.

With the advent of suburban sprawl and mass media that beamed the image of New York all over the world, the great Mountains of Manhattan could be increasingly part of a lifestyle, if not everyday life. As the ‘20s gave way to the Depression, these buildings became even more emblematic of an ideal. In the commercial center, away from the heart of family life, they weren’t necessarily places where people spent the majority of their time; instead, they gave people of taste of the lives they would like to live, offering the elegance, refinement, and excitement people thirsted for but could not necessarily maintain.

Art Deco details on the Fuller Building, via Beyond my Ken / Wiki Commons

The New Republic summed up the situation fairly well. Surrounded by the elegance and opulence of an Art Deco entertainment palace like Radio City, people “could enjoy the sense of leading a sophisticated continental life with none of the practical risks.” Accordingly, Art Deco New York made manifest a thrilling fantasy: in the Cubist dream city, forever surrounded by elegance, enlightenment, and power, it’s always time to celebrate.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

RELATED: