Skyline Wars: One Vanderbilt and East Midtown Upzoning Are Raising the Roof…Height!

Carter Uncut brings New York City’s breaking development news under the critical eye of resident architecture critic Carter B. Horsley. This week Carter brings us the second installment of nine-part series, “Skyline Wars,” which examines the explosive and unprecedented supertall phenomenon that is transforming the city’s silhouette. In this post Carter zooms in on Midtown East and the design of One Vanderbilt, the controversial tower that is being pinned as the catalyst for change in an area that has fallen behind in recent decades.

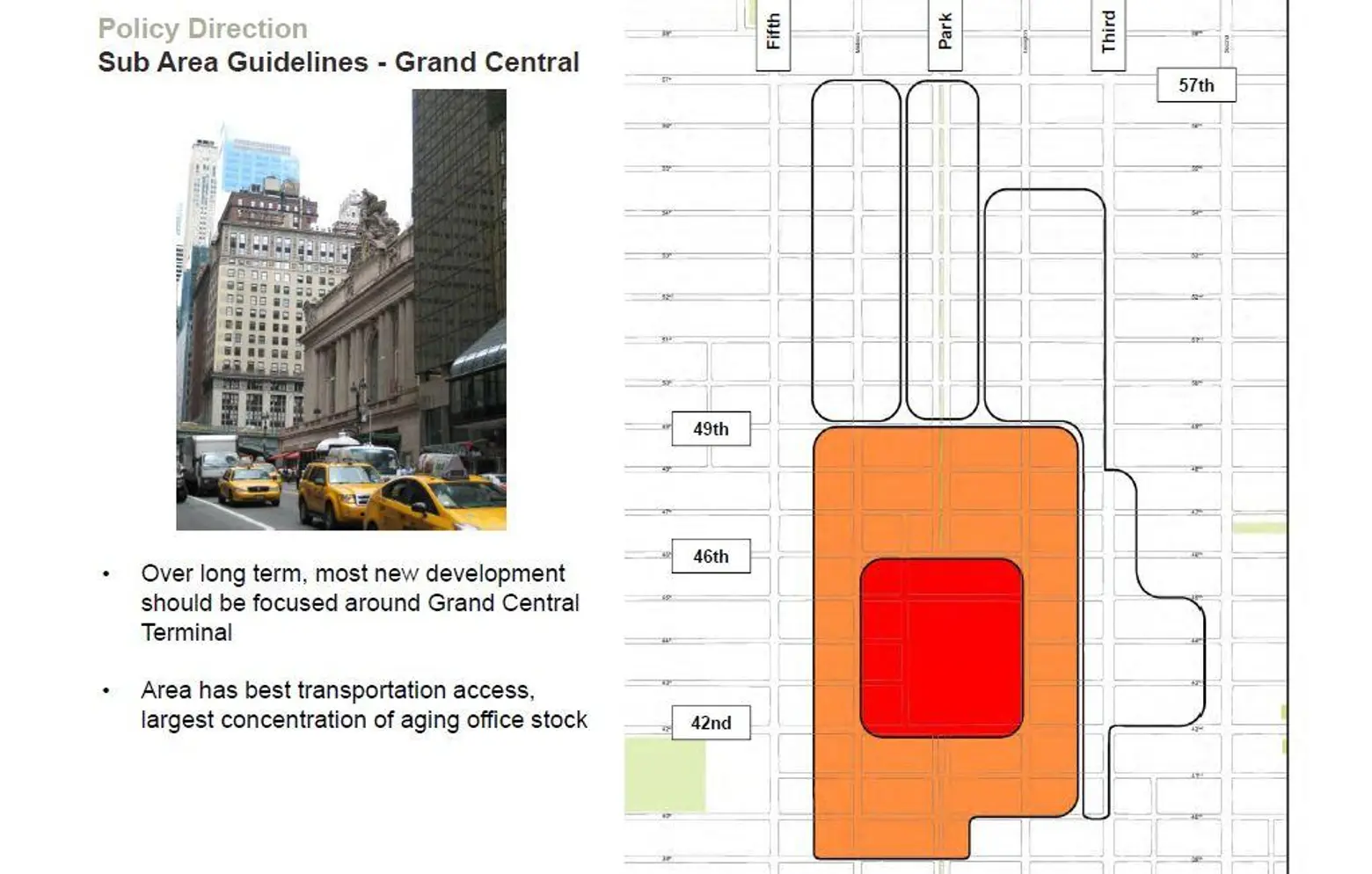

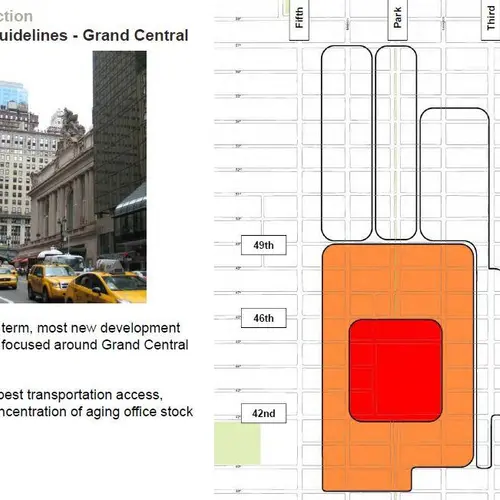

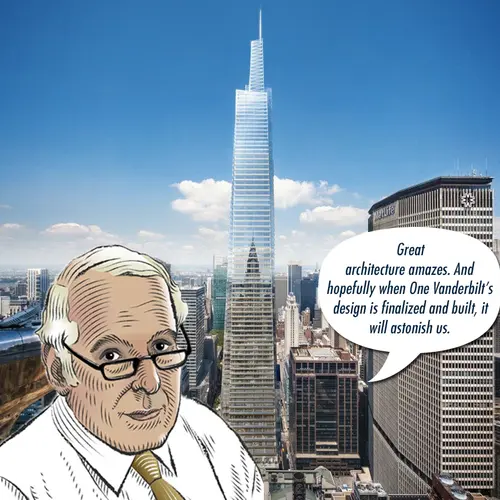

Despite some objections from community boards and local politicians, New York City is moving ahead with the rezoning of East Midtown between Fifth and Third avenues, and 39th and 59th Streets; and earlier this year, the de Blasio administration enacted an important part of the plan, a rezoning of the Vanderbilt Avenue corridor just to the west of Grand Central Terminal. The Vanderbilt Avenue rezoning included approval of a 1,501-foot-high tower at 1 Vanderbilt Avenue on the block bounded by Madison Avenue, 42nd and 43rd Streets. The tapered, glass-clad tower, topped by a spire, is being designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox for SL Green. Mayors Bloomberg and de Blasio have championed the 1 Vanderbilt proposal despite serious concerns voiced by numerous civic organizations over the rezoning scheme that some see as “spot zoning” and the fact that the city has still not finalized nor published its complete rezoning package.

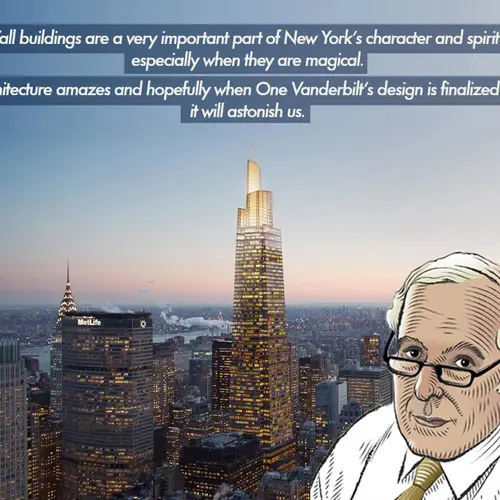

Using air-rights transfers from the Grand Central Terminal area and zoning bonuses for providing $210 million for infrastructure improvements in the area, the tower will significantly alter the midtown skyline, rising several hundred feet above the nearby Chrysler Building and the huge and bulky but lower MetLife Tower straddling Park Avenue just north of Grand Central Terminal. Its 63 stories are several less than the Chrysler Building and just a few more than the MetLife Tower, which might be interpreted by some observers as indicated that it was in “context” with such prominent neighbors, but they are wrong.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE TOWER AND THE AREA

The banded earthen and glass tower will also be higher than the Empire State Building and most of the large group of supertalls now sprouting in the 57th Street/Central Park South corridor. The proposed tower makes an attempt to draw attention visually to its famous neighbor, Grand Central Terminal, by angling its southern base along 42nd Street upward to the east, but this “arrowhead” points the wrong way.

SL Green’s website provides the following commentary about its plans for the new development:

One Vanderbilt is an iconic Class A office tower in Midtown Manhattan. The building’s design was to meet today’s market needs, but also address a civic need to strengthen the Midtown Core and the Grand Central District. Formally, the massing is comprised of four interlocking, tapering volumes that spiral up to the sky. This tapered shape creates an elegant proportion sympathetic to the shaft of nearby Chrysler Building. At the base, a series of angled cuts organize a visual procession to Grand Central Terminal, revealing the Vanderbilt corner of its magnificent cornice—a view which has been obstructed for nearly a century.

…The material palette of the design takes cues from the textured, masonry construction typical of the neighborhood—the tower wall consists of a terra cotta spandrel while terra cotta soffits and herringbone flooring are reminiscent of Gustavino tile work. Shading elements enhance environmental performance and add texture to the tower.

…An active urban base makes One Vanderbilt a 21st century successor to Rockefeller Center.

…Following the layered language of such great New York buildings as the Chrysler, the Empire State, and the Woolworth, the top of One Vanderbilt spirals up to a narrow point. A nuanced façade treatment that interplays vertical and diagonal structure against a transparent glass is also pragmatic, offering panoramic views of the city.

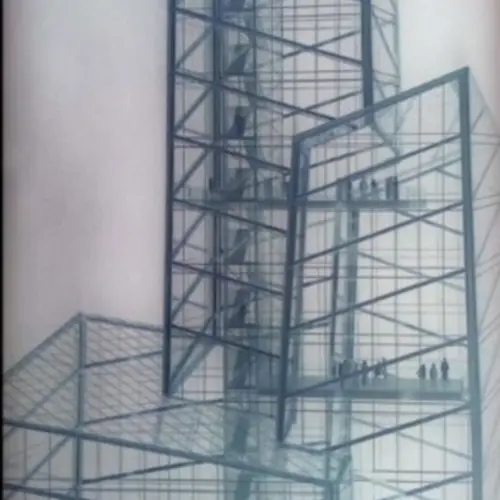

The project’s renderings are a bit confusing as the jigsaw façade angling at the top is not symmetrical. It is difficult to understand from various images what is happening within the top of the building. An early drawing indicates that the space is pretty much empty except for many staircases and a couple of viewing levels. It appears preliminary and unresolved and very confusing for such a major project that city planners have so steadfastly shepherded.

Building and architecture enthusiasts have also echoed these same sentiments, as seen in the One Vanderbilt thread at wirednewyork.com. One commenter noted that “the massing on top looks clumsy and the base looks like it’s going to swallow GCT in its glassy maws,” adding that “right now it does not merit a position near the Chrysler or Grand Central Terminal.

I will say that the proposed tower does make an attempt to draw attention visually to its famous neighbor by angling its southern base along 42nd Street upward to the east, but alas, this arrowhead points the wrong way.

View of the base of 1 Vanderbilt looking west on 42nd Street

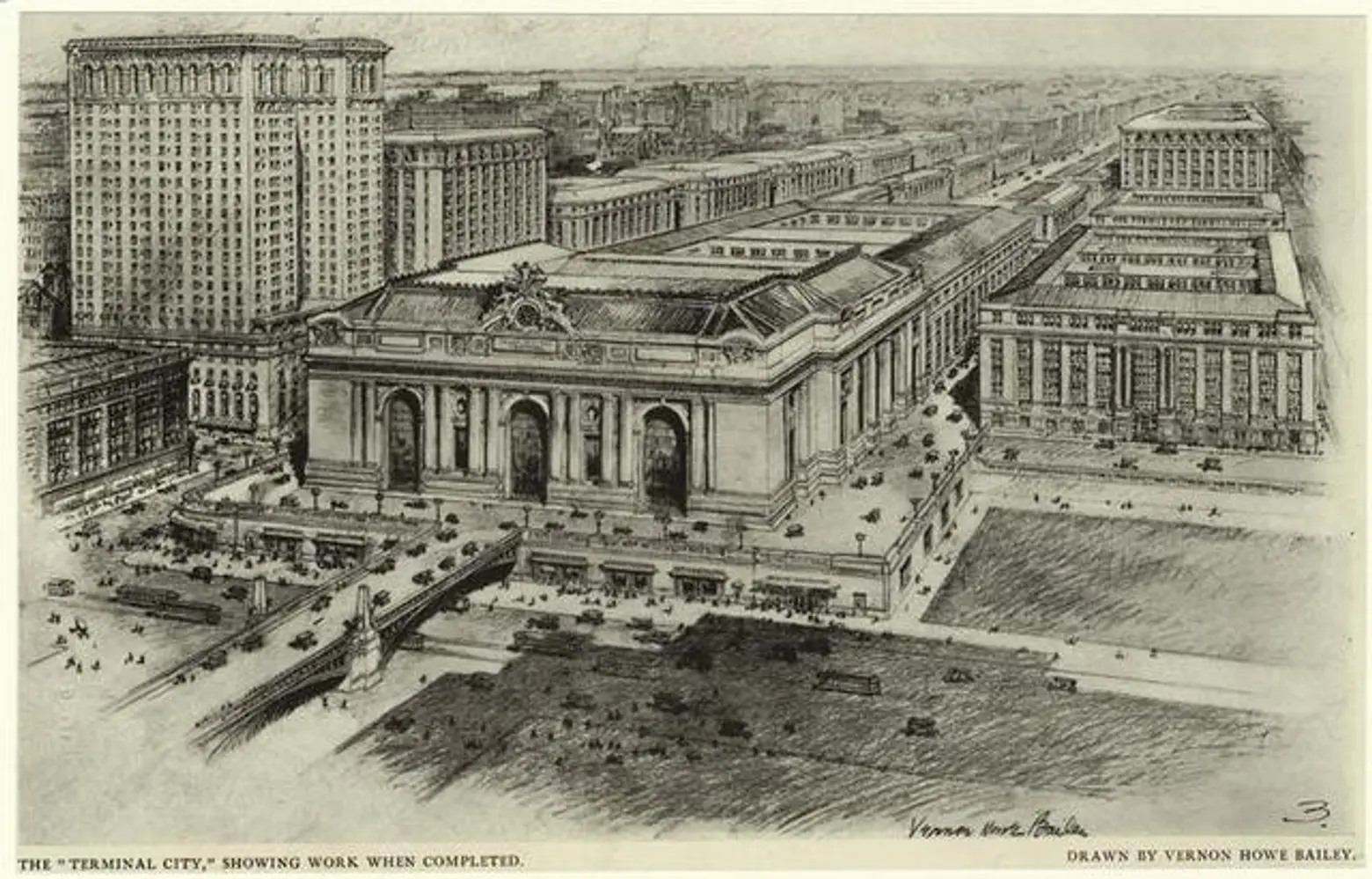

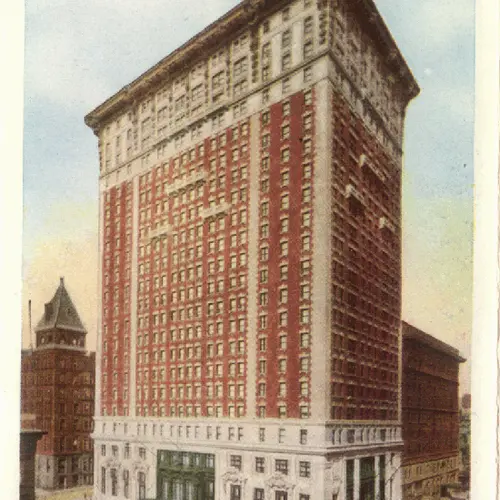

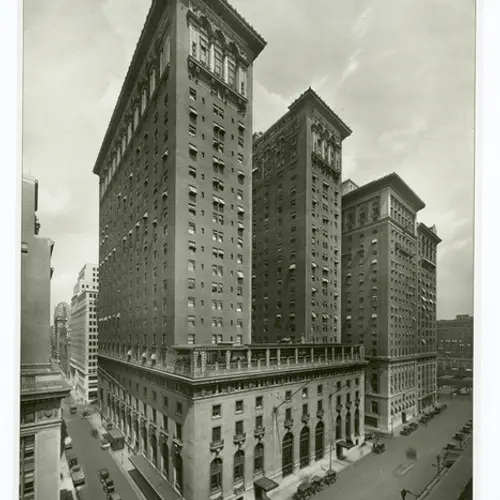

The tower’s reflective facades are also out of context with the great landmark terminal and the wonderful Terminal City Plan of elegant masonry building surrounding the train station by its two main architectural firms, Warren & Wetmore, and Reed & Stem. If the design is site-sensitive to anything, its shiny facades are in keeping with the glass that Donald Trump reclad the fine Terminal City hotel, the Commodore, with in 1976.

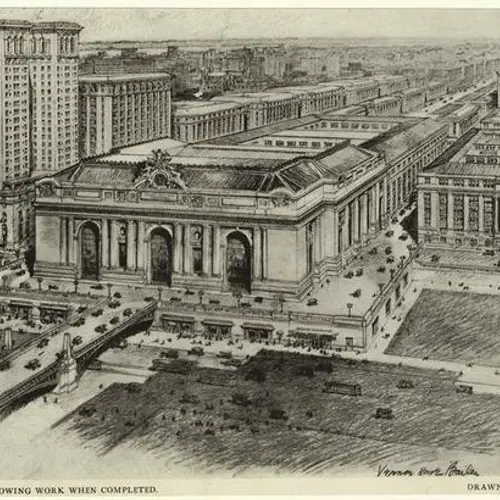

Original studies for Grand Central Terminal show Biltmore hotel at left and lots of neo-classical, Beaux-Arts style buildings up Park Avenue

The original Commodore Hotel designed by Warren & Wetmore, left, and Donald Trump’s Grand Hyatt Hotel reconstruction of it designed by Der Scutt, right

Terminal City was two decades ahead of Rockefeller Center as the nation’s finest urban plan, and press reports cite the Roosevelt Hotel as a prime candidate for major redevelopment under the rezoning. The Commodore was not the only Terminal City hotel to go under the knife. Other fine Terminal City hotels demolished nearby were the Belmont at 120 Park Avenue across 42nd Street from the terminal and the Ritz Carlton on the west side of Madison Avenue between 45th and 46th streets.

The original Biltmore Hotel, designed by Warren & Wetmore, left next to Yale Club on northwest corner of Vanderbilt Avenue and 44th Street, left; and the Milsteins’ polished granite reconstruction of it by Environetics into Bank of America Plaza, right

The venerable and elegant Biltmore Hotel that occupied the block just to the north of One Vanderbilt survived, in a way. In August 1981, the Milsteins gutted the structure and applied a brutish but striking deep red polished granite façade. The hotel previously had one of the city’s most famous meeting places under its dining room clock. The handsome building, with its indented fenestration and sunken entrance at its base, is known now as the Bank of America Plaza Building.

Only the Roosevelt Hotel, occupying the block between Vanderbilt and Madison Avenue and 45th and 46th Streets, remains with its Terminal City architecture handsomely intact, but it and the Milstein building are strong contenders to be replaced with huge new towers under the Vanderbilt Corridor zoning as is the wonderful Yale Club that only occupies about half a block on Vanderbilt between the Milstein and Roosevelt. Several decades ago, I urged Kent Barwick, then chair of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, to create a masonry office building district around Grand Central Terminal to prevent glassy conversions of what then still existed as Terminal City. Unfortunately, Mr. Barwick was pre-occupied with other concerns and the economics of the day, making such concerns seem a bit far-fetched whereas today everything seems to be up for grabs with no heed to preservation, sound planning principles and the special sanctity of extraordinary skysights.

All three are very large in bulk by most urban standards but pale in skylineness with the city’s new crop of supertalls.

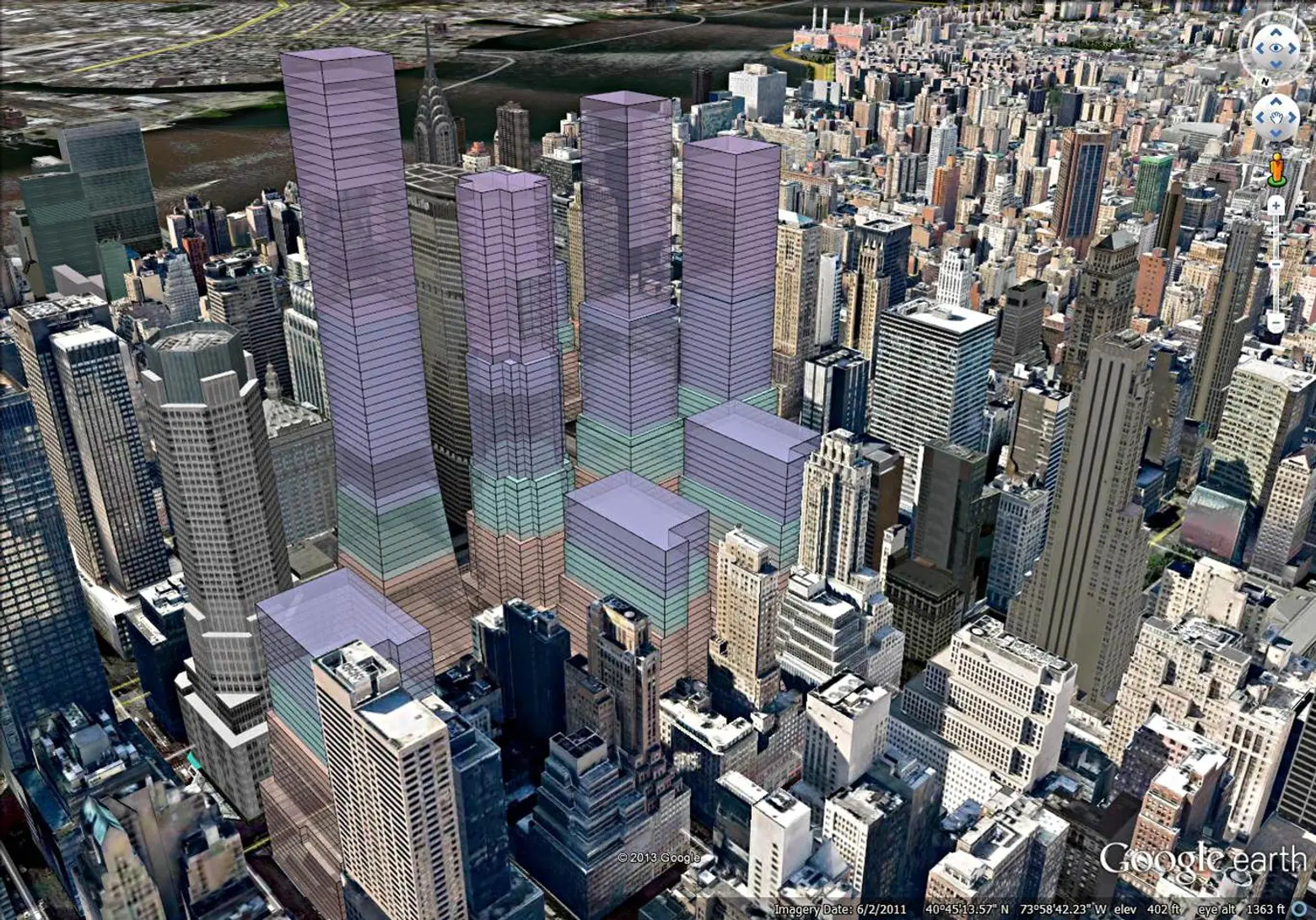

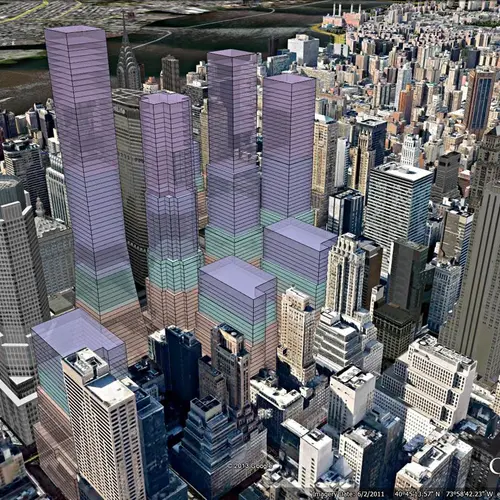

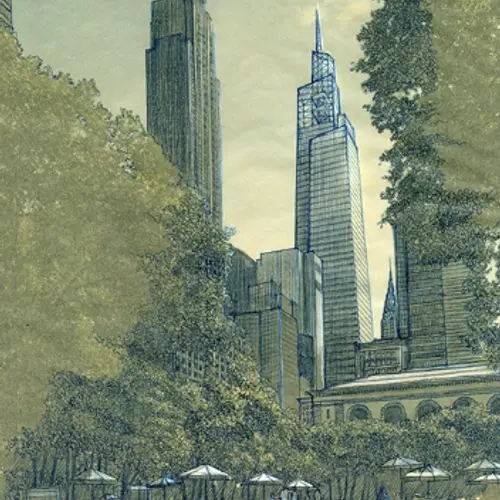

A 2013 City Planning Department rendering of how Vanderbilt Avenue might be redeveloped under zoning then under consideration and prior to the design of One Vanderbilt, which is significantly taller than this rendering’s other possible redevelopments

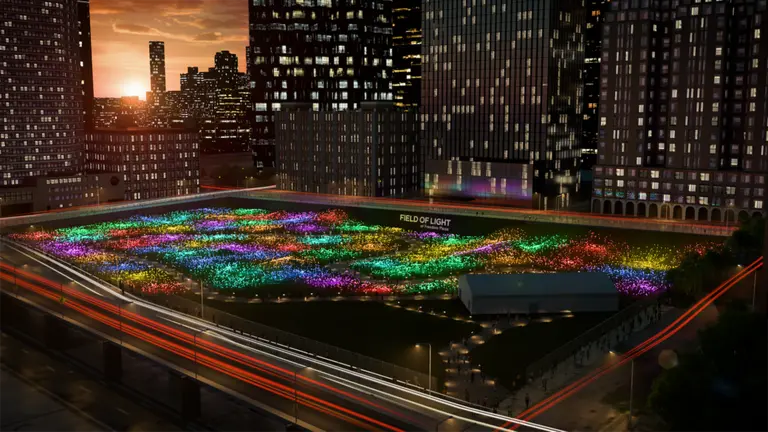

Conceptual image depicting all the proposed sites of the East Midtown rezoning fully built out. Courtesy TJ/CityRealty

IN THE PAST, THE CITY WAS MUCH MORE CRITICAL

The question of air-rights transfer has long been contentious and the city has historically kept its skyline lid sliver-proof, that is, it has not encouraged towers that shatter the “roof” of the city in a haphazard fashion.

In a November 1983 article I wrote for The New York Times, First Boston Real Estate, then headed by G. Ware Travelstead, was acquiring most of the two million square feet of unused air rights that remain over Grand Central Terminal with the plan of erecting a 140-story tower on the block bounded by Vanderbilt and Madison Avenues and 46th and 47th Streets at 383 Madison Avenue. At the time, an official of the Penn Central Corporation, which then owned the air rights, said the agreement with the partnership “eliminates forever the threat of building over Grand Central Terminal.”

In a June 1988 article in The New York Times, Alan Oser wrote that “over the years Penn Central has succeeded in using only 75,000 square feet of the 1.8 million square feet of unused rights above the terminal site,” adding that “some were transferred across 42nd Street to what is now the Philip Morris Building.”

Although Mr. Travelstead and his partners had contracted to buy 1.5 million square feet of the rights, he altered his plan to use only 800,000 square feet to produce a building of 1.4 million square feet in a 72-story, 1,040-foot-high tower, incidentally also designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox.

The city, however, never certified the plan as “complete” for land-use review. The developer sued and the city appealed, arguing that the developer’s plan to establish a legal link for the transfer was dependent on “underground tax lots.” The city’s regulations allowed transfers to “contiguous lots” but did not specific “surface” lots.

Rendering of the unbuilt Travelstead Tower at 383 Madison Avenue

As such, in August 1989, the New York City Planning Commission unanimously rejected the 383 Madison Avenue plan on the basis that the “chain of ownership” was not created by the underground lots and that the proposed skyscraper “would have been far too big.” Its report maintained that “even if the proposed transfer were legally eligible, we would nonetheless be compelled to deny the application because of the excessive bulk and density proposed.”

The proposed tower was, in fact, about 500 feet shorter than One Vanderbilt Avenue.

Bear Stearns eventually built a major office tower on the site designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox, using only 285,866 square feet of Grand Central’s air rights.

THE STATE OF AFFAIRS

The city in 1982 enacted a Special Midtown District to restrict heights in East Midtown to encourage major development in Times Square and ten years later the city created the Grand Central subdistrict to permit air rights transfers from the terminal and other area landmarks to new developments to a maximum FAR (Floor-to-Area-Ratio) of 21.6. Today, the Vanderbilt Corridor district now permits FARs of 30.

Vanderbilt Corridor rezoning area (Phase I)

One Vanderbilt is the first project to take advantage of the city’s new East Midtown Rezoning, which is actually still a work in progress. The City Council unanimously approved Phase I, the rezoning of the Vanderbilt Corridor on May 27, 2015, and city council member Daniel Garodnick said that it was “time to unlock the economic development potential in East Midtown,” adding that “the area has gotten stuck in outdated rules, and has lost some of its competitiveness over time.” SL Green hails that its new tower would “usher in an exciting new era for East Midtown” and “deliver critically-needed, state-of-the-art Class A office space and dramatically upgrade Grand Central’s aging, over-burdened transit infrastructure.”

In a March article at Real Estate Weekly online, Steven Spinola, the head of the Real Estate Board of New York says that the One Vanderbilt tower “is exactly the type of dense, transit-oriented development that belongs immediately adjacent to Grand Central Terminal” and will help “launch the revitalization of this section of East Midtown and pave the way for a rezoning of the greater Midtown East area.” Spinola also notes, “last week, it was reported that Howard Milstein is planning to develop a completely new modern tower at 335 Madison Avenue,” the former site of the Biltmore hotel. “This rezoning could trigger even more development than expected,” he said.

Shortly after the approval of Phase I, Garodnick delivered the keynote address at the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce on the larger 73-block East Midtown Zoning and said that Phase II will allow larger developments near transit locations with increased density earned by improvements to area infrastructure and a broader transfer of air rights from landmarks to anywhere in East Midtown. In return, a percentage of each sale must be given to the city for public improvements.

As part of the larger Phase II rezoning, the East Midtown steering committee has recommended a proposal to city planners that would free up landmarked properties to sell the space above their properties, or unused air rights, anywhere within the East Midtown zoning district. The cost of the development rights would be negotiated by the buyer and seller.

Landmarks like St. Patrick’s Cathedral, or St. Barts or Central Synagogue, or even Grand Central itself will be able to sell their air rights throughout the entire district, whereas now, such sales are limited now to adjacent properties. The city would then take a percentage of each sale of development rights and put those funds toward public improvements in the district.

One project that did not wait for the city’s rezoning to take advantage of its inflated development rights is 425 Park Avenue where L & L Holding Company, which is headed by David W. Levinson, has decided to proceed with an 893-foot-high tower with three slanted setbacks using the same amount of square footage now on the site in a much shorter building. The design of three tall fins at the top by Sir Norman Foster recalls the razor-sharp, three-blade “hand” that the villain in “Enter the Dragon” used, unsuccessfully, of course, to fight Bruce Lee.

Map of the 73-block greater East Midtown rezoning Area

The East Midtown Rezoning presents a great and likely rapid up-scaling of one of the city’s most important neighborhoods. Historically, New York has inched upwards with great consistency, and only very rarely in great leaps. The great leaps have been, by and large, up to now, fine architecture: the Metropolitan Life Building, the Woolworth, Chrysler and Empire State Buildings, the Emery Roth towers on Central Park West and the World Trade Center.

As in the aforementioned cases, when such exceptions are grand, the urban soul is uplifted. Tall buildings are a very important part of New York’s character and spirit especially when they are magical. Great architecture amazes. And hopefully when One Vanderbilt and the collection of towers envisioned for East Midtown are finalized and built, they will astonish us.

RELATED:

- New Renderings and Video of One Vanderbilt, Midtown’s Future Tallest Office Tower

- New Renderings of One Vanderbilt Show the 1,500-Foot Tall Tower Set in the Skyline

- One Vanderbilt Tower Receives Unanimous Approval from City Council

- All One Vanderbilt coverage on 6sqft

+++

Carter is an architecture critic, editorial director of CityRealty.com and the publisher of The City Review. He worked for 26 years at The New York Times where he covered real estate for 14 years, and for seven years, produced the nationally syndicated weeknight radio program “Tomorrow’s Front Page of The New York Times.” For nearly a decade, Carter also wrote the entire North American Architecture and Real Estate Annual Supplement for The International Herald Tribune. Shortly after his time at the Tribune, he joined The New York Post as its architecture critic and real estate editor. He has also contributed to The New York Sun’s architecture column.

Explore NYC Virtually

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

An excellent, thoughtful piece of reportage and analysis. As an amateur architecture critic myself, I share Horsley’s opinion of the dollar-driven overdevelopment now taking place in midtown. Guaranteed whatever improvements are made to transportation and infrastructure in the area will be insufficient to handle the increased pedestrian and automotive traffic these buildings will generate. I’m particularly incensed by the zillion-story residential building (still!) rising at 432 Park, a middle finger to all of Manhattan that relates to absolutely nothing else on the island. Is it my imagination, or did the builders deliberately eschew a glass curtain wall that would’ve reflected the sky and helped the building blend in a touch in favor of a window treatment delineating each floor individually in order to rub our noses in its gargantuan height?