Remembering the worst disaster in NYC maritime history: The sinking of the General Slocum ferry

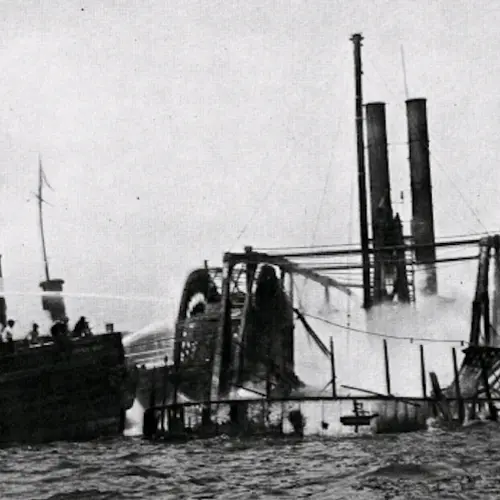

PS General Slocum; photo via Wikimedia

On June 15, 1904, a disaster of unprecedented proportions took place in New York City, resulting in the loss of over 1,000 lives, mostly women and children. This largely forgotten event was the greatest peacetime loss of life in New York City history prior to the September 11th attacks, forever changing our city and the ethnic composition of today’s East Village.

It was on that day that the ferry General Slocum headed out from the East 3rd Street pier for an excursion on Long Island, filled with residents of what was then called Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany. This German-American enclave in today’s East Village was then the largest German-speaking community in the world outside of Berlin and Vienna.

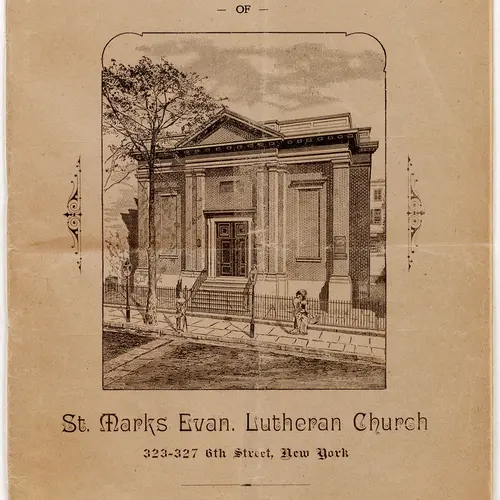

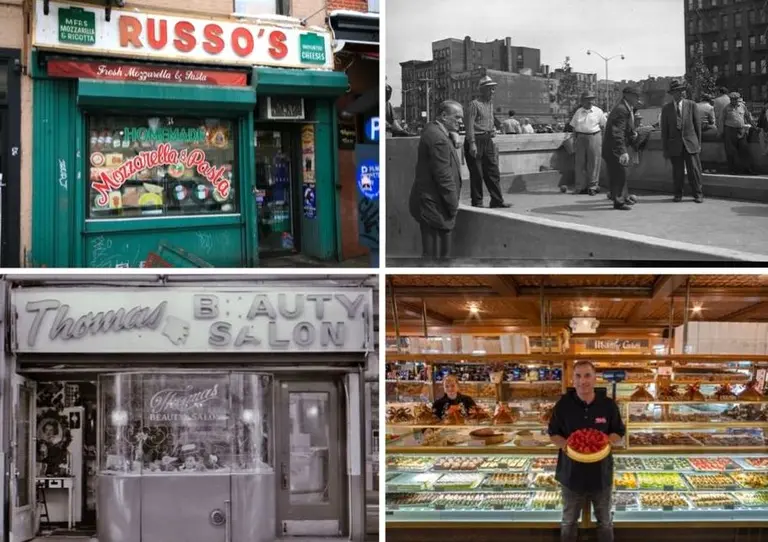

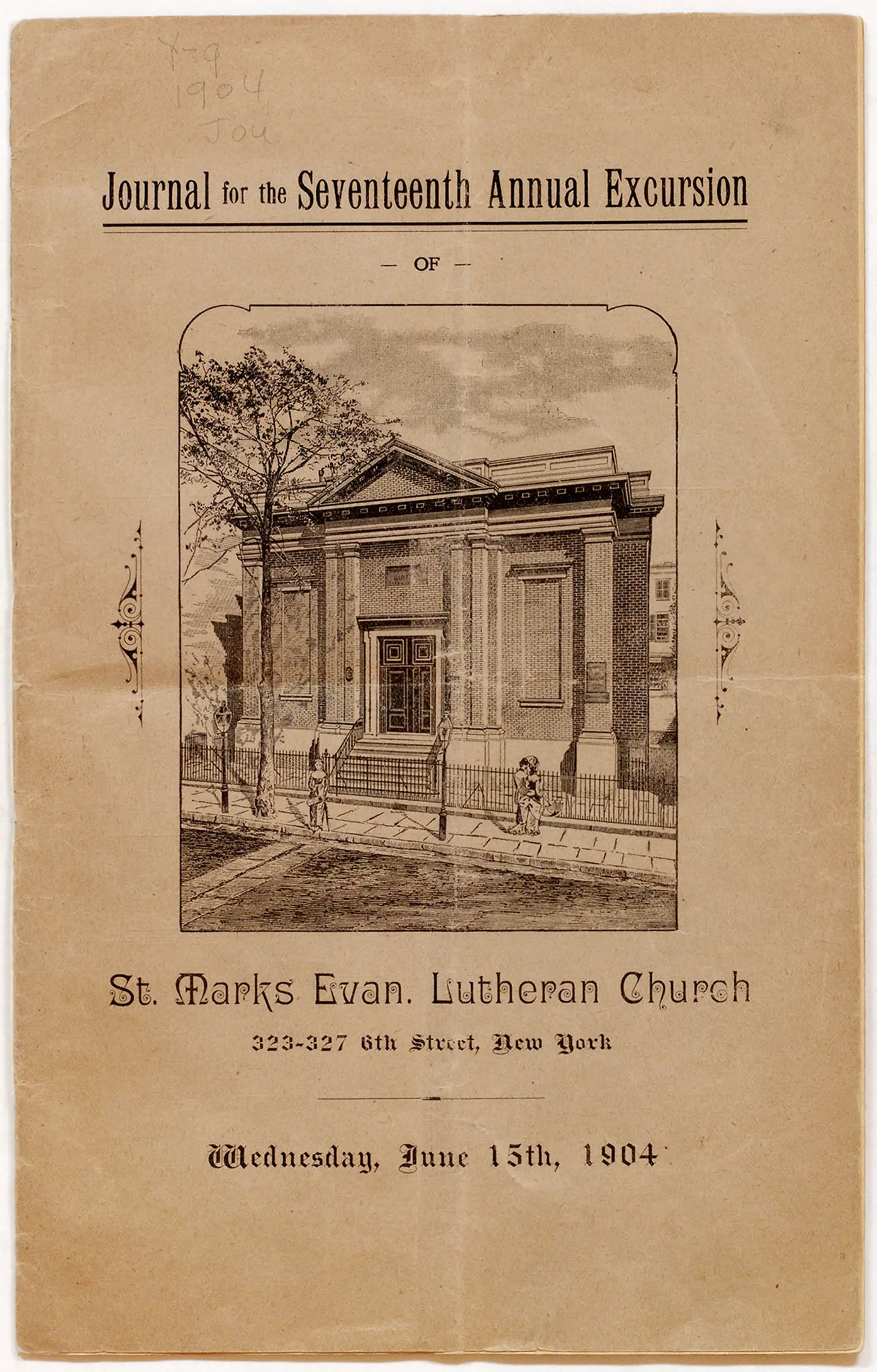

Journal for the 17th annual excursion of St. Marks Evan. Lutheran Church (1904); via New-York Historical Society

About 1,342 people departed on the boat chartered by the St. Mark’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church, located at 323 East 6th Street between 1st and 2nd Avenues, for an annual excursion up the East River and through Long Island Sound to Eaton’s Neck on Long Island.

While the church had made this trek sixteen times before without incident, the General Slocum, unfortunately, had a much more checkered record. The ship had run aground several times and been involved in several collisions. But none of these prior incidents matched the breadth of the tragedy which would take place that summer day.

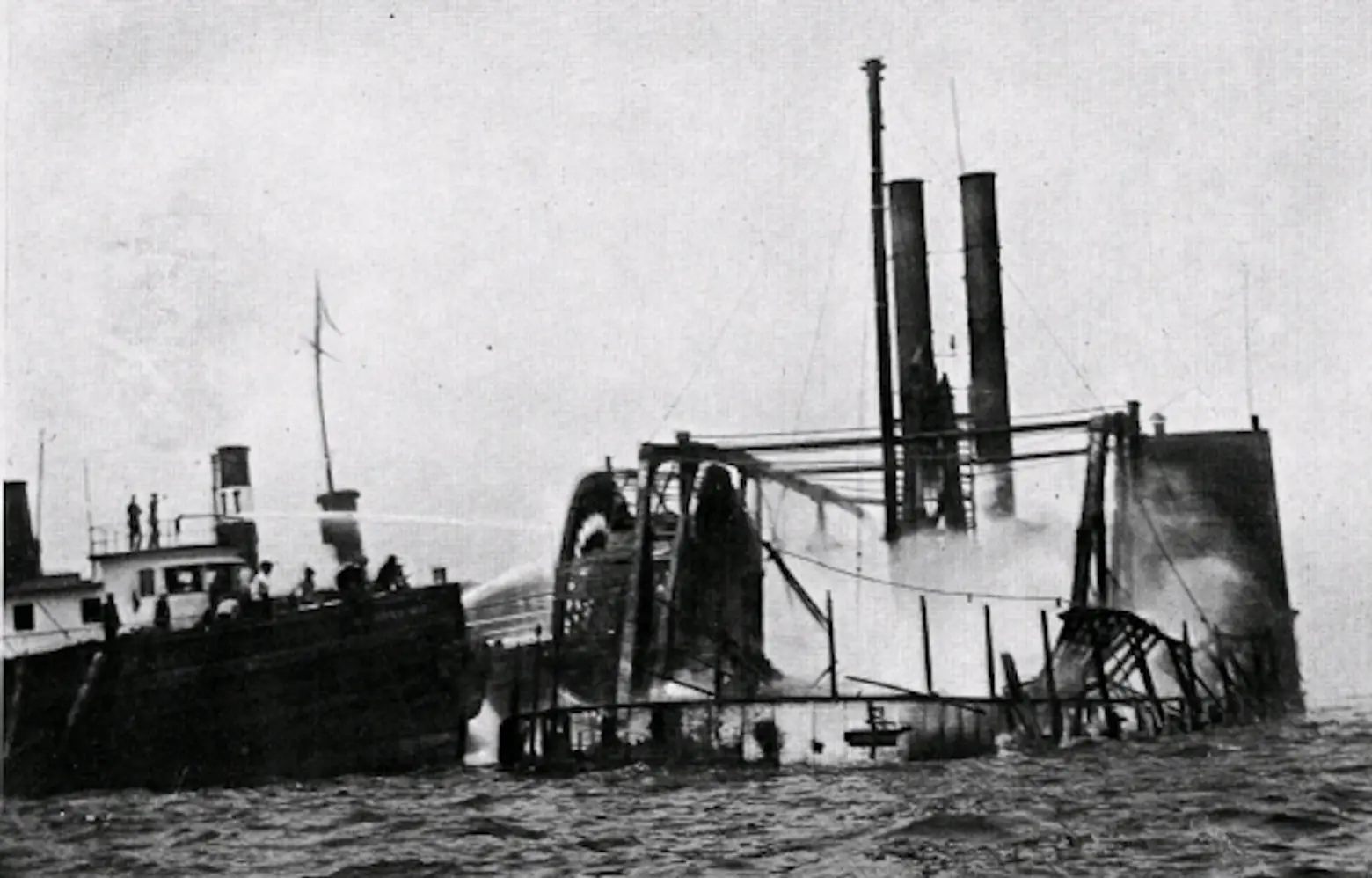

Firefighters working to put out the fire on General Slocum via Wikimedia

Shortly after departing from the Lower East Side waterfront, a fire broke out in the lamp room of the boat as it passed East 90th Street. The fire spread rapidly, aided by ample flammable material and a lack of working fire safety features. The boat’s fire hoses had not been maintained and rotted through, falling apart when the crew tried to use them to put out the fire. The lifeboats were tied in place and unusable.

As the fire quickly spread and the ship began to lilt, more desperate measures were pursued by passengers and crew. Many jumped ship or, in the case of children, were thrown overboard in the hopes they could make it to shore. But for too many, this was a fatal mistake.

The wreck of General Slocum (1904); via George E. Stonebridge Photograph Collection, New-York Historical Society

According to survivors, the boat’s life preservers did not work. Some fell apart in their hands. Others were placed on children who found, when in the water, that they actually weighed them down rather than buoying them, hastening their demise. Many were more than 12 years old, and had been exposed to the elements and not maintained during that time. Some survivors claimed they had been filled with cheaper less effective granulated cork, embedded with iron weights to feel like they were made of appropriate materials – a deadly combination when actually used in the water in an attempt to stay afloat.

Unfortunately, other factors did not aid in the passenger’s chances for survival. In the early 20th century, many fewer people could swim than now, especially those who lived in crowded urban environments. Most were wearing the heavy wool clothing common at the time, which when wet further weighed them down. And the section of the East River where the tragedy took place, not far from the notorious ‘Hell’s Gate,’ was known for its swift and treacherous currents.

The ferry captain also made some tragic errors which deepened the tragedy. Rather than run the ship aground or stop at nearby landings, he continued onward into the headwinds along the river, thus literally and figuratively fanning the flames of the disaster.

Tending to the Slocum victims (1904); via George E. Stonebridge Photograph Collection, New-York Historical Society

Eventually, the boat began to come apart, and many passengers drowned when the floorboards collapsed. Others who tried to jump into the river were struck by the ship’s turning paddles. The boat eventually sank just off North Brother Island near the Bronx. All told, an estimated 1,021 people died, one of the worst naval disasters in American history.

The devastation had a profound effect on the German-American community of the Lower East Side. Nearly every family was affected in some way, losing members, neighbors, or both. Reminders were everywhere of the tragedy, and of those who died. And the loss of almost 1,000 women from this community meant that men seeking wives had to look elsewhere.

Rather quickly in the years that followed, the German-American community – once the largest of the many ethnic groups on New York’s Lower East Side – disappeared. Survivors sought to escape the sorrow attached to the neighborhood or to find new opportunities for families. Many of the former residents of this neighborhood moved to Yorkville on the Upper East Side, Bushwick in Brooklyn, or Ridgewood and Maspeth in Queens.

This was also around the time that Jewish immigration to New York City was peaking. Within a decade or so, nearly all of Kleindeutschland was occupied by Jewish residents; some from Germany, but mostly poorer Jews from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires. By World War I, and the anti-German fervor that it raised, the German-American presence in this part of the Lower East Side all but disappeared.

However, even to this day, reminders remain, particularly of the General Slocum disaster. St. Mark’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church still stands on East 6th Street, though in 1940 it became the Community Synagogue. A plaque on the building memorializes the victims of the General Slocum disaster.

General Slocum disaster memorial in Tompkins Square Park; via Wikimedia

In Tompkins Square Park, the Slocum Memorial Fountain was dedicated in 1906 to the victims of the disaster and remains to this day. The pink Tennessee marble fountain was donated by the Sympathy Society of German Ladies and shows two children looking seaward, over a lion’s head which spouts water.

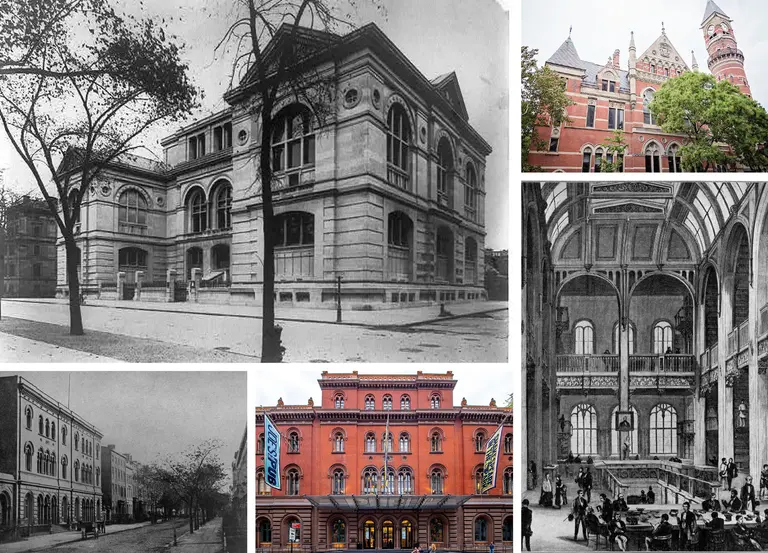

And on St. Mark’s Place west of 2nd Avenue, in the heart of what had been Kleindeutschland, the Deutsch-Amerikanische Sheutzen Gesellschaft (German-American Shooting Society), or Scheutzen Hall as it’s more commonly known, still stands at No. 12.

Here met the Organization of General Slocum Survivors, founded by the Liebenow family. Anna Liebenow was a young mother whose face was permanently scarred by burns she received on the Slocum while seeking to save her six and a half-month-old daughter Adella. Anna was able to save Adella but lost two of her other daughters, two of her nieces, and two of her sisters.

Adella lived to 100, passing away in 2004. She was the last living survivor of this unspeakably tragic and often-overlooked episode in New York City history.

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED: