12 historic Italian-American sites of the East Village

October, the month we mark Columbus Day, is also Italian-American Heritage and Culture Month. That combined with the recent celebrations around the 125th anniversary of beloved pastry shop Veniero’s inspires a closer look at the East Village’s own historic Little Italy, centered around First Avenue near the beloved pastry shop and cafe. While not nearly as famous or intact as similar districts around Mulberry Street or Bleecker and Carmine Street in the South Village, if you look closely vestiges of the East Village’s once-thriving Italian community are all around.

In the second half of the 19th century, the East Village was a vibrant checkerboard of ethnic enclaves. Germans were by far the dominant group, until the turn of the century when Eastern European Jews took over the Second Avenue spine and much of what’s now Alphabet City, Hungarians congregated along Houston Street, and Slavs and Poles gravitated towards the blocks just west and north of Tompkins Square. But a linear Italian-American enclave formed along and near First Avenue, broadening at 14th Street. Vestiges of this community survived into the third quarter of the 20th century, with just a few establishments and structures connected to that era continuing to function today.

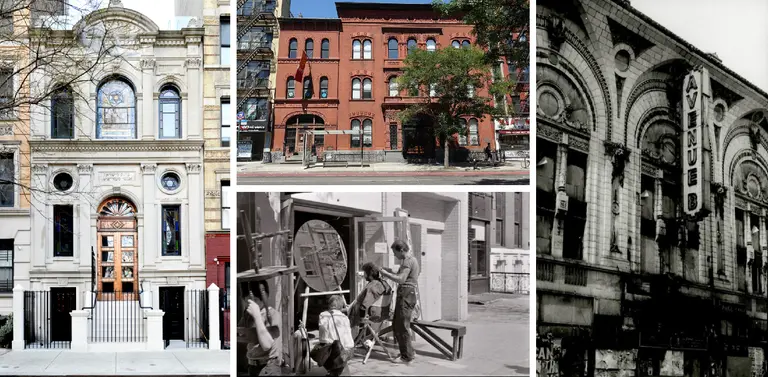

“Thomas Beauty Salon, 231 East 14th Street between 2nd & 3rd Aves (now ‘Beauty Bar’),” Village Preservation (GVSHP) Image Archive

1. Italian Labor Center

231 East 14th Street

Starting north and moving south along the First Avenue spine, the first stop is this six-story office building between 2nd and 3rd Avenues. Built in 1919, the building originally housed the Cloakmakers Local 48 of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. In New York in the early 20th century, nearly all of the women garment workers were Jewish or Italian, and while they often worked closely together, there were also separate organizations and entities catering to differences of language and culture. The dramatic relief marble carvings on the building depicting workers’ struggle against exploitation are believed to be the work of poet and sculptor Onorio Ruotolo. In the 1920s, after Mussolini’s takeover of Italy, the Center was a hub of anti-Fascist organizing in New York.

It’s been decades since the Italian Labor Center left its quarters, replaced at first by a Ukrainian fraternal organization. The building is now perhaps best known for housing Beauty Bar on its ground floor, the popular watering hole which began the trend of keeping the signs and names from old on-site businesses when turning them into hip new hangouts.

Photo by Beyond My Ken on Wikimedia

2. Moretti Sculpture Studio

249 ½ East 13th Street

Next stop is this incredibly charming little building located just west of 2nd Avenue. Located in the rear yard of neighboring 215 Second Avenue, the building at 249 1/2 East 13th Street was constructed in 1891 as a sculptor’s studio at a time when rear stables were frequently converted to artist’s studios. As a result, the building was designed to look like it was originally a stable, though it never was (a conceit which became more and more common with artist’s studios built in New York in the early 20th century, such as on MacDougal Alley and Washington Mews). It was constructed for sculptors Karl Bitter and Giuseppe (or Joseph) Moretti, both of whom lived in the apartment building at 215 Second Avenue, with Moretti is listed as the original owner of the studio. Bitter and Moretti’s names are carved into the stone of the studio’s 13th Street facade.

Moretti, a native of Sienna, Italy, began studying as a marble sculptor around the age of nine. When he immigrated to America, he had already worked as a sculptor throughout Italy, Croatia, Austria, and Hungary. Moretti gained great fame as a sculptor in America, working with architects such as Richard Morris Hunt and for patrons including the Vanderbilts and the Rothschilds. His statue Vulcan in Birmingham, Alabama, is the largest cast-iron sculpture in the world, and he is said to be the first person to use aluminum in sculpture.

3. “The Black Madonna”

447 East 13th Street

In the early 20th century East 13th Street between 1st Avenue and Avenue A served as a center of Sicilian religious custom and ritual that, while ostensibly Catholic, operated outside the sanction of the formal Catholic Church. The street had a series of private “storefront chapels” that venerated religious figures rooted in the old country. Perhaps the most interesting one is the chapel of the Black Madonna at 447 East 13th Street.

Located in a small space on the ground floor of a tenement and next to Rotella’s funeral parlor, the chapel housed a stucco statue of the Black Madonna of Tindari (a city in Sicily), which was credited by believers with possessing curative powers. The Black Madonna tradition extends back to at least the Middle Ages, and veneration of the statue, which stood in the window, took place each year starting in 1909 on a feast day on Sept. 8. The tradition continued until 1987 when the chapel closed and the statue was given to a family in New Jersey.

For the past 20 years gay bar The Phoneix has occupied the space, where Madonna can be heard playing from time to time. A group of Italian-American scholars, artists, and friends have held a reunion of sorts each year in early September in the space to mark the day of the feast.

4. The Festival of St. Lucy (La Fiesta de Santa Lucia)

East 12th Street

This painting by John Constanza shows a festival in 1930 honoring Saint Lucy (Santa Lucia) on East 12th Street between 1st Avenue and Avenue A. Celebrated annually in December, it is also known as the Festival of Lights, meant to look forward to the return of longer and brighter days as the weeks progress. The painting appears to show the statue of St. Lucy in the ground floor of the tenement at 413 East 12th Street, which is buttressed by our research which says that the ground floor of the building was originally used by a church, and the cornice which contains the name “G. De Bellis,” indicating at the very least that the building was originally built by Italian Americans. The site was just up the block from Mary Help of Christians Church.

Photo by Village Preservation on Flickr

5. Mary Help of Christians Church

440 East 12th Street

In many ways the heart of the East Village’s Italian American community was this church which stood for nearly 100 years between 1st Avenue and Avenue A. Built between 1911 and 1917, the church was based upon the Basilica of Mary Help of Christians in Turin. For decades, the beautiful, twin-towered church served a largely-Italian-American congregation, which got more diverse as the 20th century progressed. The church did however also inspire two very prominent non-Italians; Alan Ginsberg lived across the street for many years at 437 East 12th Street and mentioned the church frequently in his poetry, and Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement, worshipped here.

In 2007 the archdiocese closed the church. Village Preservation and neighbors railed to save the church and call for its landmarking, but the city allowed it to be demolished, along with the church’s school and rectory. A new luxury condo development named “The Steiner” was built on the site, in spite of it being home to a large cemetery, which many believe human remains still lay.

© Village Preservation

6. John’s of 12th Street

302 East 12th Street

First opened in 1908, John’s of 12th Street prides itself on combining traditional Italian “red sauce” cuisine with updated vegan options. Owned by the founding Pucciatti family until 1972, the restaurant has changed hands a few times since then, but the sense of connection to the East Village’s Italian roots remains unchanged.

John’s old-world atmosphere and historic connections to mob figures has made it a favorite for film and TV shoots over the years (John’s was the scene of a huge power shift within La Cosa Nostra; after mobster Joe Masseria survived a point-blank shot in 1922, revenge was taken on the Gambino family’s Rocco Umberto Valenti right outside by Lucky Luciano among others, elevating Masseria to leader of the family). Anthony Bourdain, Guy Fieri, and Boardwalk Empire are just a few of those who have filmed here over the years (the latter noting that John’s was a speakeasy during Prohibition).

Photo © James and Karla Murray for 6sqft

7. Veniero’s

342 East 11th Street

Established in 1894, this cherished East Village institution is at this point the granddaddy and the long-term survivor of the East Village’s Little Italy. Antonio Veniero, a Neapolitan immigrant, opened the shop 125 years ago, and it has remained in the family ever since. Current proprietor Robert Zerilli grew up in New Jersey, but began working in the store at the age of 18 and lived over the shop for a while. In an oral history with Village Preservation, Zerrilli discusses customers as varied as Mario Cuomo, Joey Ramone, and Hillary Clinton. Veniero’s is famed for its cheesecake, biscotti, cannoli, tiramisu, and sfogliatelle. While food is its mainstay, the establishment originally opened as a pool hall with pastry and coffee available to customers. Veniero’s consistently receives rave reviews for its pastry and deserts.

Photo by Vincent Desjardins on Flickr

8. Russo Mozzarella and Pasta Shop

344 East 11th Street

If you’re still craving Italian but want something a little more savory or substantial, just head next door to Russo Mozzarella and Pasta Shop, a cheese and pasta shop which serves homemade fresh mozzarella, cured meats, ripe vegetables, breads, and, of course, a wide range of different cheeses and pasta. Really an Italian grocery with freshly made food, you can get prepared takeaway like a sandwich or products to bring home and make your own delicious creation. Founded in 1908 at this location, they also have two outposts in Brooklyn.

Photo by Eden, Janie and Jim on Flickr

9. De Robertis Pasticceria and Caffe,

176 First Avenue

This beloved New York institution located at the heart of the East Village’s Little Italy strip on First Avenue first opened its doors on April 20, 1904. Founded by Paolo DeRobertis, he originally called it Caffe Pugliese in honor of his hometown of Puglia, Italy. Paolo eventually went back to Italy but gave the business to his son John, who began working there when he was 10 years old. He worked there every day of his life until he was 83. Through more than 11 decades of operation, including a stint as (of course) a speakeasy during Prohibition, DeRobertis stayed in the hands of the family of its original founder.

Like other nearby Italian eateries, DeRobertis’ appeal was equal parts delicious menu and irreplaceable decor and atmosphere. The pasticceria was renowned for its original ornately-tiled floors, hand-cut mosaic wall tiles, and pressed-tin ceilings. Customers over the years (often there for film shoots) included Woody Allen, Jennifer Beals, Spike Lee, Sarah Jessica Parker, Denzel Washington, and Steve Buscemi.

But by 2014, Paolo’s four grandchildren who owned the business, motivated by age and health concerns, among other factors, decided it was finally time to close up shop after 110 years. After the building (which the DeRobertis family-owned) was sold, in 2015, Black Seed Bagel moved into the space. Owners Noah Bernamoff and Matt Kliegman decided to not only keep the neon “DeRobertis Pastry Shop” sign on the exterior but to retain much of the original decor and fixtures on the interior.

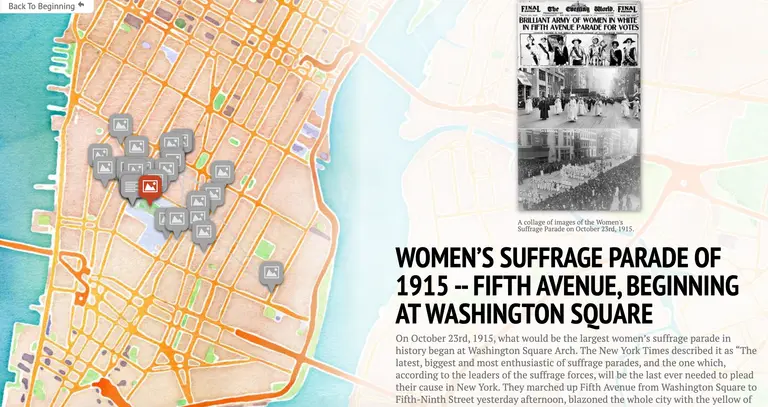

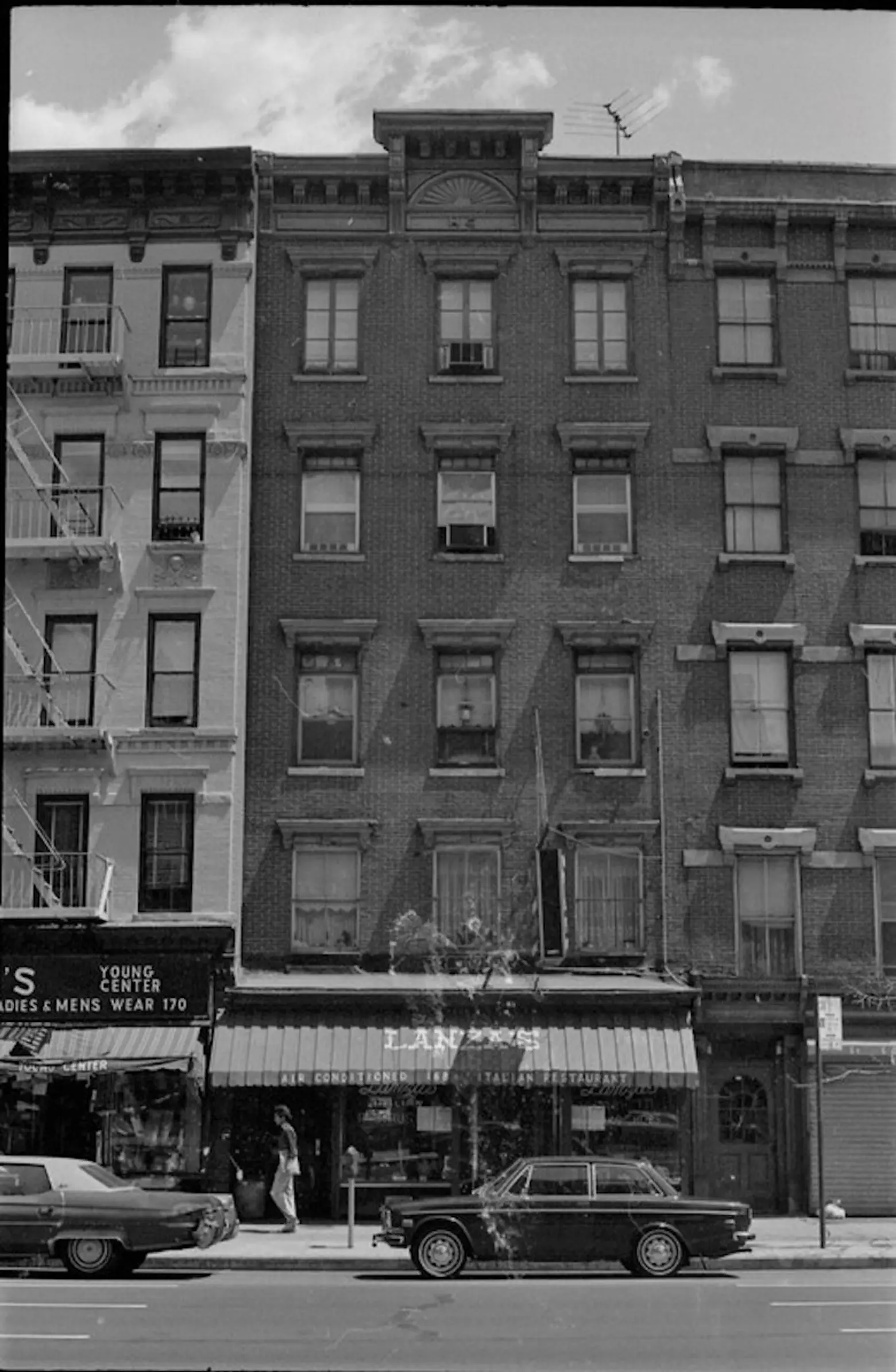

“166, 168, & 170 1st Avenue between 10th & 11th Streets, east side, Lanza’s Italian Restaurant,” Village Preservation (GVSHP) Image Archive

10. Lanza’s Restaurant & the Provenzano Lanza Funeral Home

168 First Avenue, 43 Second Avenue

Lanza’s restaurant was opened in 1904 by Sicilian-born Michael Lanza, an immigrant who was rumored to have served as chef to the Italian King Vittorio Emmanuel III and remained in operation at this site for over 100 years. The eatery was beloved not just for its food but its decor, which included large painted murals of places like Mount Vesuvius, and stained glass windows on the entryway with ‘Lanza’s’ in it, and a tin ceiling, all of which dates to the earliest days of the restaurant. Like John’s and De Robertis’, Lanza’s was a speakeasy during Prohibition.

The combination of old-world cuisine and decor attracted a loyal following, including more than a few notorious mob figures. One was Carmine “Lilo” Galante, who along with several members of his Bonanno crime family could often be seen soaking up (and adding to) the atmosphere at Lanza’s. So fond was Galante of Lanza’s that after he was assassinated in 1979, his funeral service was held at the Provenzano Lanza Funeral Home just a few blocks away on Second Avenue, which was owned by the same Lanza family. The restaurant’s maître d’ and co-owner at the time, Bobby Lanza, was the mortician in charge of the funeral service.

By the 21st century, ownership of Lanza’s had left the family, though the restaurant maintained the menu, decor, and atmosphere for which it was known and loved. Sadly in 2016 after 112 of operation Lanza’s closed its doors, replaced by Joe and Pat’s Pizzeria, an Italian eatery founded in 1960 on Staten Island’s Victory Boulevard.

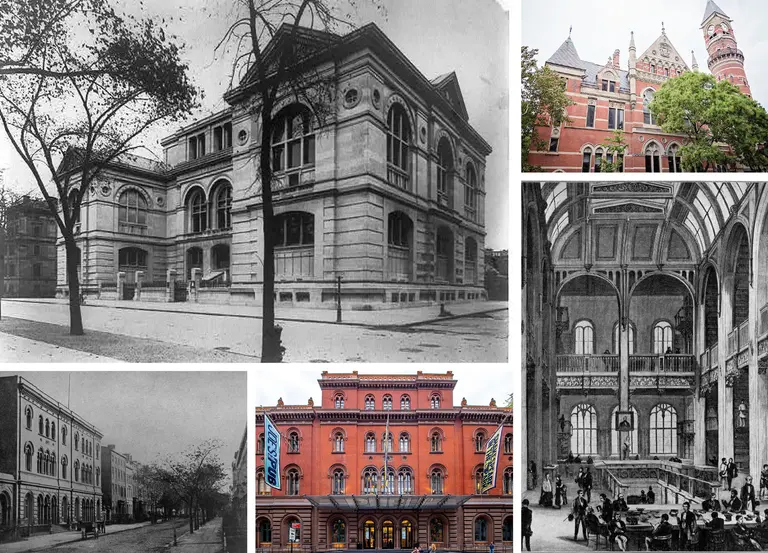

11. First Avenue Retail Market

155 First Avenue

One of the signature projects of Fiorello LaGuardia, New York’s first Italian-American mayor (who was born just a few blocks away in Greenwich Village) was getting all of the peddlers and carts off of New York’s overcrowded streets and into safe, modern, sanitary indoor marketplaces. Dozens of these were built across the city, all bearing a similar Works Project Administration-inspired Art Deco streamlined look, giving thousands of merchants for the first time a controlled environment within which to sell their goods and millions of New Yorkers a more orderly place within which to shop for them.

One of the first and largest of these markets was the First Avenue Retail Market, opened in 1938 by none other than Mayor LaGuardia himself. Located in the heart of the East Village’s Little Italy, it was chock full of vendors selling cheeses, meat, olives, and other Italian delicacies as well as other kinds of food.

Of course, after World War II, these indoor markets, which were the cutting edge of modernity when they opened, were being rapidly replaced by the new innovation of supermarkets. By 1965 the First Avenue Retail Market had closed, its space taken over by the Department of Sanitation. Fortunately, by 1986 a new use was introduced–The Theater for the New City–which showcases avant-garde writers and performers whose work might not be seen elsewhere.

“Bocce Court at First Park, from 1st Street west of 1st Avenue looking southeast to the south side of East Houston Street, east and west of Allen Street,” Village Preservation (GVSHP) Image Archive

12. First Avenue Bocce Courts

The game most associated with Italian-American New Yorkers is bocce, and for decades a large bocce court announced the beginning of the East Village’s Little Italy at the base of First Avenue between Houston Street and First Street. Right next to the busy Second Avenue F subway stop, it was one of the most popular bocce courts in the city.

It was also, along with one at Thomas Jefferson Park in East Harlem (then also an Italian-American neighborhood) the first municipal bocce courts in the city, constructed sometime around 1940. Built by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, they were eventually found in parks and playgrounds in or near predominantly Italian-American neighborhoods across the city.

Like much of the East Village’s Little Italy, however, the bocce courts eventually disappeared along with the changing demographics of the neighborhood. The courts remained until sometime in the mid-1970s, and have since been replaced with a children’s playground, handball courts, and a café in what is known as ‘First Park.’

+++

This post comes from Village Preservation. Since 1980, Village Preservation has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid