How the East Village grew to have the most community gardens in the country

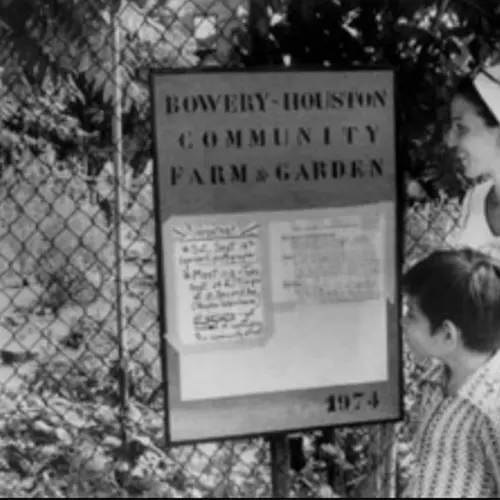

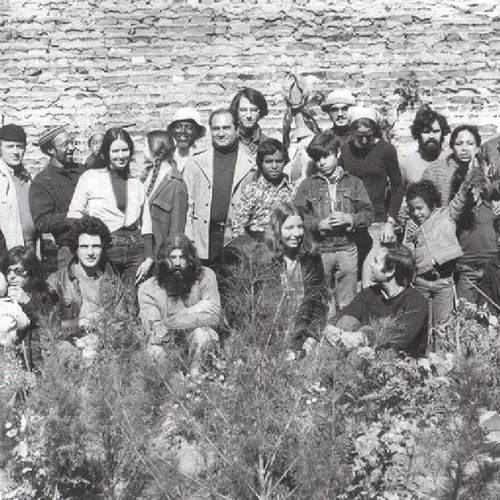

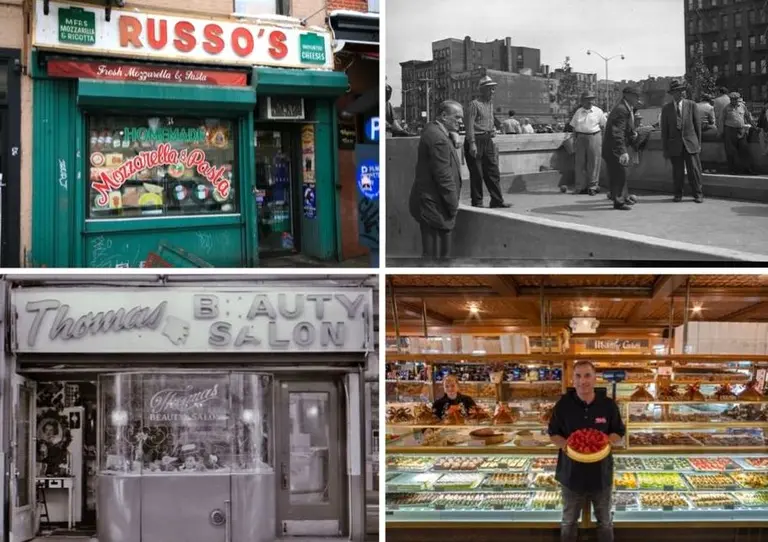

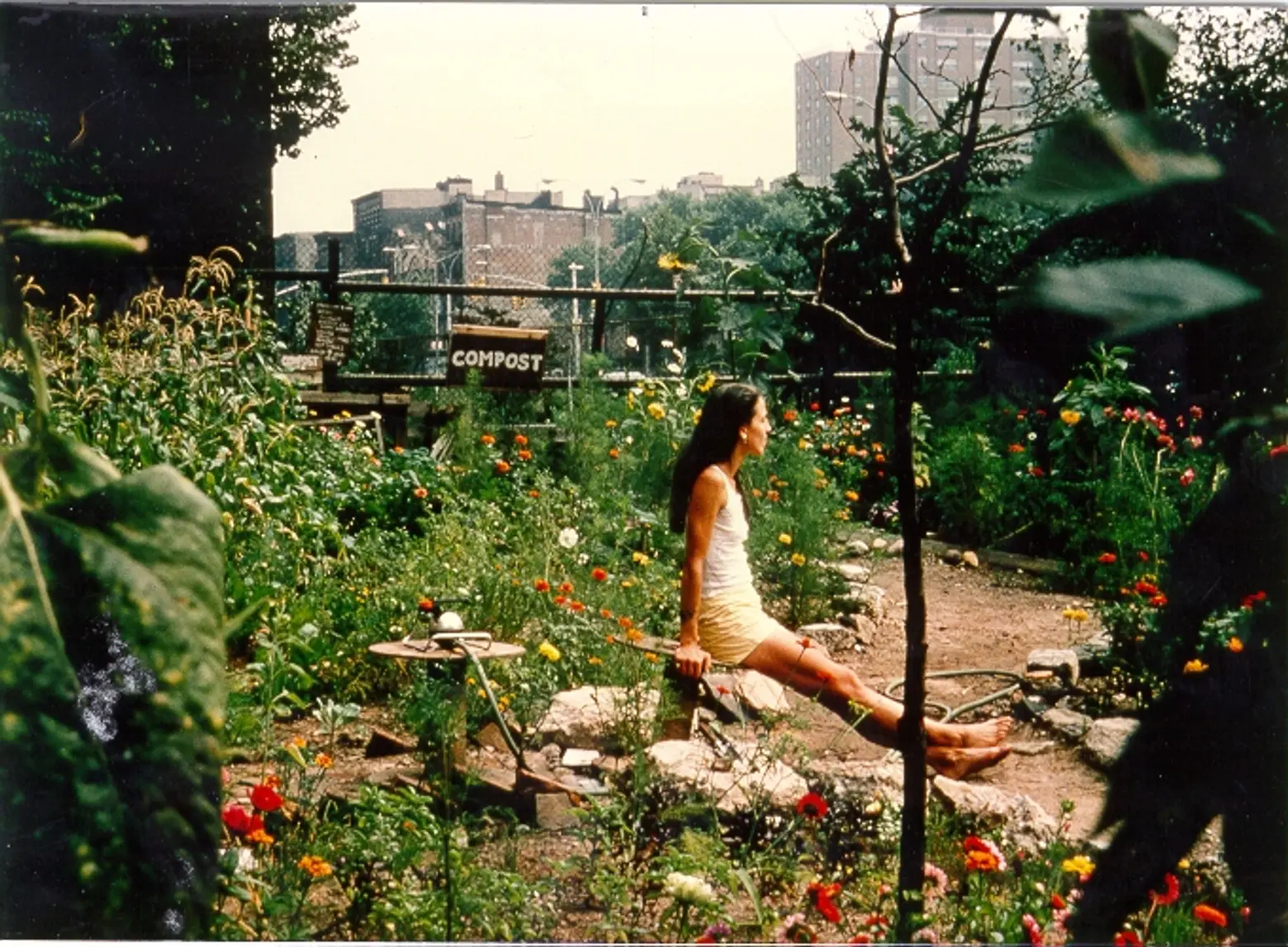

Community Gardeners at the Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden, 1974 via Liz Christie Community Garden

Awash in gray pavement and grayer steel, New York can be a metropolis of muted hues, but with 39 community gardens blooming between 14th Street and East Houston Street, the East Village is the Emerald City. The neighborhood boasts the highest concentration of community gardens in the country thanks to a proud history of grassroots activism that has helped transform once-abandoned lots into community oases.

By the mid-1970s, as the city fought against a ferocious fiscal crisis, nearly 10,000 acres of land stood vacant throughout the five boroughs. In 1973, Lower East resident Liz Christie, who lived on Mott Street, refused to let the neglected lots in her neighborhood lie fallow. She established the urban garden group Green Guerillas, a rogue band of planters who lobbed “seed bombs” filled with fertilizer, seeds, and water into vacant, inaccessible lots, hoping they would flourish and fill the blighted spaces with greenery.

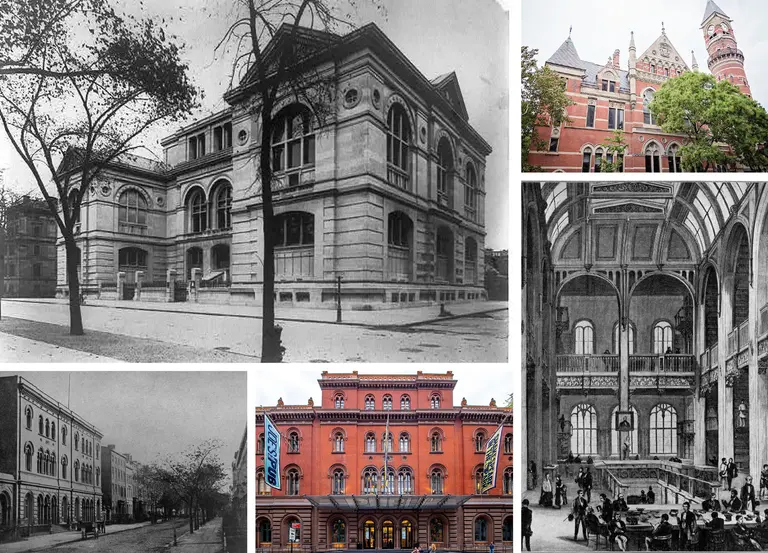

Working the Land at the Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden, 1973 via Liz Christie Community Garden

That year, Christie and the Guerillas also turned their attention to a vacant lot on the northeast corner of the Bowery and Houston Street, where they established New York City’s very first community garden, the Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden. Volunteers removed trash from the site, added topsoil and fencing, planted trees, and built 60 vegetable beds. The City Office of Housing Preservation and Development recognized their efforts in 1974, and allowed the community to lease the garden for $1 per month. The garden still flourishes as The Liz Christie Community Garden.

The Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden helped inspire the more than 600 community gardens that flourish across New York City today, and created a citizen-stewardship model of environmental activism that transformed the way New Yorkers experienced their public parks.

In the 1850s, New York began setting aside major tracts of land for public parks. Central Park emerged as the first major landscaped public park in the nation. It stood out as a stunning oasis, and as the lungs of the city, but citizen-stewardship was not a part of its design. When Fredrick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed Central and Prospect Parks, their goal was to educate the public about art and beauty; these parks were paragons of the City Beautiful Movement, a design philosophy that promoted social and moral uplift through inspiring architecture and benevolent landscaping: New Yorkers could be redeemed simply by patronizing the perfect parks.

But the community garden movement grew out of a more hands-on “City Bountiful” tradition of Farm Gardening, an educational movement that kept city kids well versed in the finer points of vegetable cultivation. Fannie Griscorn Parsons established the city’s very first Farm Garden at DeWitt Clinton Park in 1902. On three-quarters of an acre in the park, she created 360 plots where children, who were bereft of playgrounds or after-school activities, could cultivate the land.

New York’s original farm gardeners were kids aged nine to 12, who grew plants, flowers, and veggies like corn, beets, peas, and turnips, and learned to cook their harvest in the park’s onsite farmhouse. Parsons explained that the urban farming program helped teach children values like economy of space, neatness, order, honesty, justice, and kindness towards their neighbors. By 1908, farm gardens were part of the curriculum at 80 schools across the city.

By the onset of WWI, farm gardens weren’t just for children. The Farm Garden Bureau established a model garden in Union Square to educate New Yorkers about combatting wartime food shortages by cultivating their own vegetables.

When the Depression brought on even greater shortages throughout the 1930s, the WPA financed “subsistence gardens” in the city’s parks. The organization assigned subsistence plots to individual families, along with training and supervision. According to the Parks Department, the substance gardens operated in every borough except Manhattan, and by 1937, Parks officials noted that they had yielded 1,215,270 million pounds of vegetables, including 330,279 pounds of tomatoes, 87,111 pounds of corn, 86,561 pounds of beets, and 84,913 pounds of turnips.

In the 1970s, citizen growers moved out of the city’s parks and into its abandoned lots. Foreclosed and abandoned buildings were a veritable pandemic throughout the city in those years, but New Yorkers banded together to revitalize their neighborhoods.

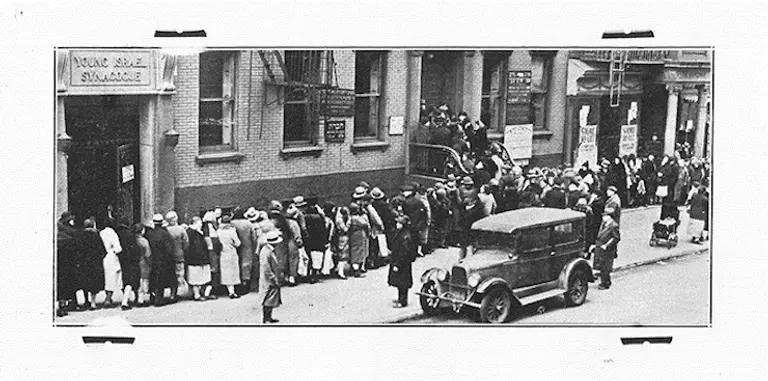

The lot that became the The Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden via Liz Christie Community Garden

The lot that became the The Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden via Liz Christie Community Garden

Community gardeners turned what the New York Times called “a scene from a nightmare of decaying cities” into the New Life Garden on Avenue B and 9th Street, complete with cherry trees, plums, pears, and petunias. The Times pointed out that the children who helped cultivate the garden saw “so much destruction around here, but they really care about this.” The paper editorialized, “caring is one of the essentials for creating and keeping a city community garden. That and hard work.”

Care and hard work led to major community greening initiatives throughout the 70s. For example, New York’s first city-wide community greening conference was held at the church of St. Marks in the Bouwerie in April, 1975. The meeting, sponsored by the New York Botanical Garden and the Green Guerillas advocated for “space to grow in,” and encouraged New Yorkers to “Turn a Lot into a Spot!”

Over 300 people attended that first meeting with the intent to turn vacant lots verdant. Liz Christie knew that such a broad outpouring of support was necessary for the gardens to flourish. She told the Times, “With a broad base, you will have less trouble with vandalism, and you will get a lot more money and cooperation.” She also advocated for regular garden meetings, “so that people will feel real involvement with the whole project, and not just their own plot.”

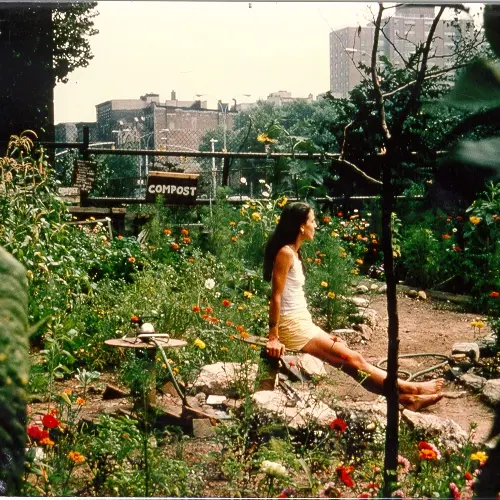

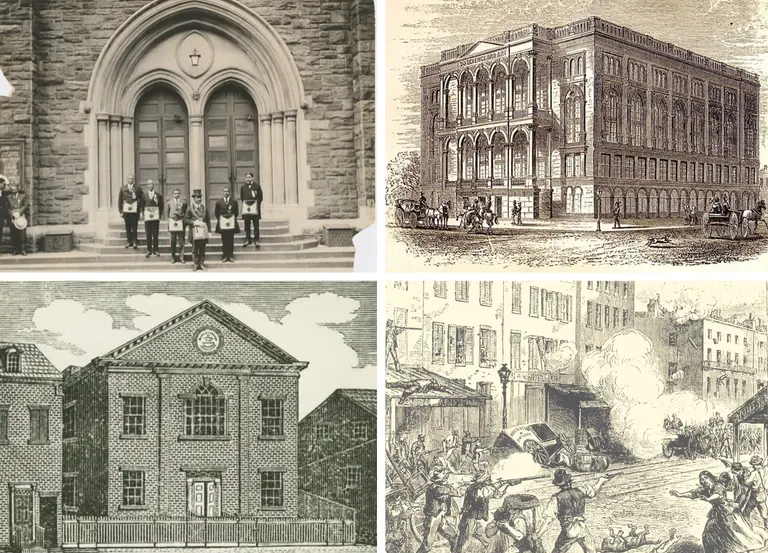

Liz Christie in the flourishing Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden, ca. 1970s via Liz Christie Community Garden

Liz Christie in the flourishing Bowery Houston Community Farm and Garden, ca. 1970s via Liz Christie Community Garden

Her desire to create a city-wide community garden coalition led Christie to host “Grow Your Own,” a radio show devoted to urban forestry, community gardens, environmental stewardship, and community oriented urban planning. She also pioneered the City Council on the Environment’s Urban Space Greening Program, and in 1978, she developed the Citizen Street Tree Pruner’s Course that trains New Yorkers to care for their trees as well as for their communities. That same year, the Parks Department inaugurated the GreenThumb Program.

Since the 1970s, New York’s community gardens have flourished and citizen activism to protect them has grown apace. In the 1980s, the Koch administration issued five- and 10-year leases for community gardens. When those leases expired under Mayor Giulliani, community gardens throughout the city were bulldozed, and their parcels were auctioned off.

Community groups like More Gardens! have been advocating for community gardens since the plots began being targeted by developers in the ‘90s. Such community action has moved City Hall to make concessions like the 2002 Community Gardens Agreement and the 2017 Urban Agriculture bill.

Today, urban farms like Brooklyn Grange and Eagle Street Farm flourish throughout New York, and this city has the largest network of community gardens in the nation. You can find a map of the city’s community gardens here, or sign up for the citizen pruners tree care course pioneered by Liz Christie and given by Trees NY here.

RELATED:

- Living Lots map helps New Yorkers transform vacant land into community spaces

- The Only Two Living Things in NYC to Have Been Landmarked Are Trees

- This 1970s East Village Windmill Was Decades Ahead of Its Time

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.