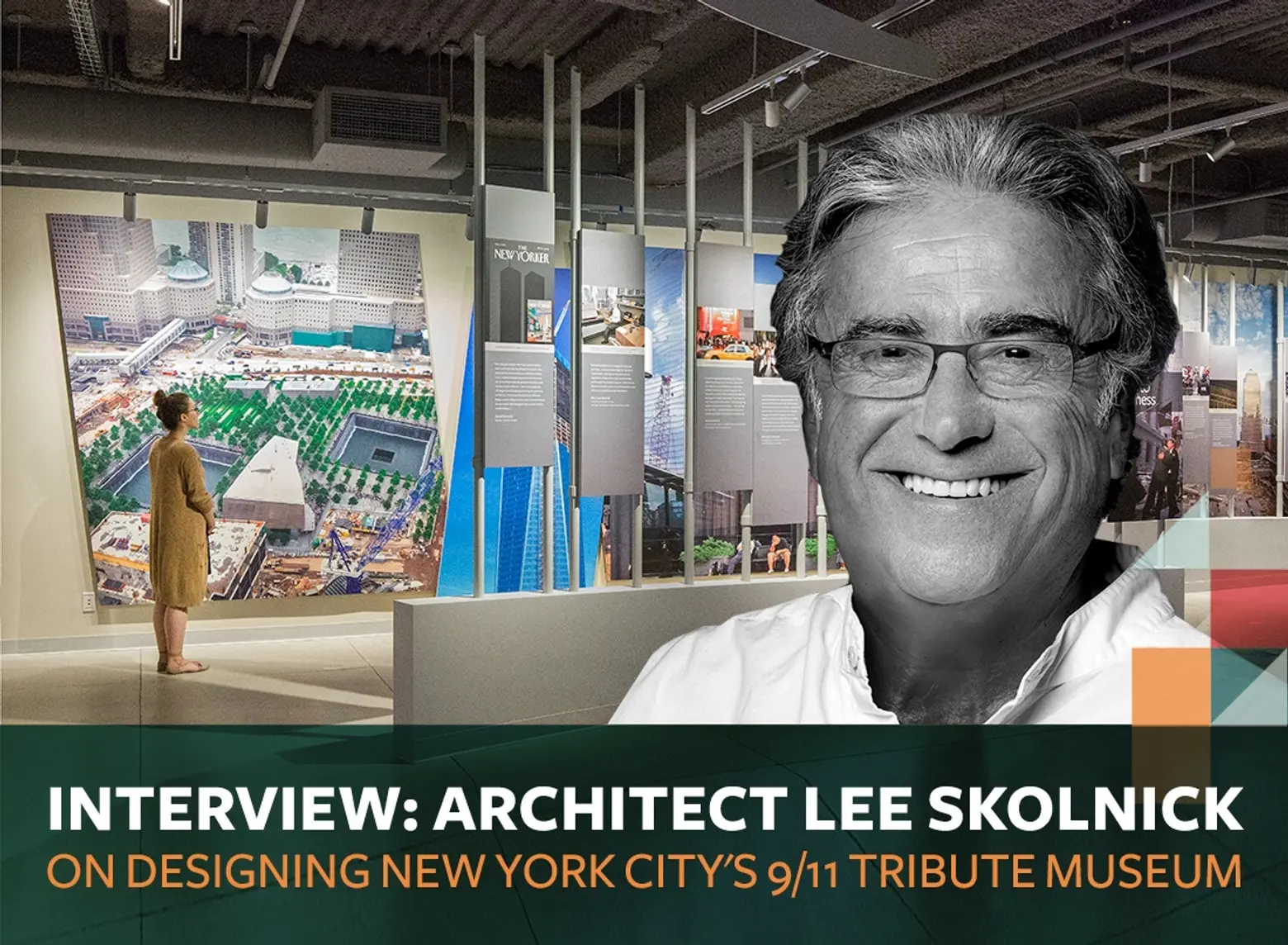

INTERVIEW: Architect Lee H. Skolnick on designing New York City’s 9/11 Tribute Museum

This summer, the 9/11 Tribute Museum opened in a brand-new space at 92 Greenwich Street in the Financial District. The 36,000-square-foot gallery became the second iteration of the museum which originally occupied the former Liberty Deli from 2006 until earlier this year. While many are more likely to be familiar with the 9/11 Memorial Museum just a few blocks up the street, the Tribute Museum differs in that rather than focusing on the implications of the tragedy, documenting the events as they unfolded and examining its lasting impact, it assumes a more inspired take, dedicating its exhibits and installations to the stories of the survivors, first responders, relatives of victims, and others with close connections to the tragedy who found hope in the terror and stepped up to help their fellow New Yorkers.

Ahead, Lee Skolnick, principal of LHSA+DP and lead architect of the 9/11 Tribute Museum, speaks to 6sqft about the design and programming of this important institution, and how he hopes its message will inspire visitors to do good in their communities during these uncertain times.

How did your firm get involved with the design of the museum?

Skolnick: We were invited along with about three or four other firms to submit designs. As a New Yorker, this project became very close to my heart. I lived downtown and suffered through 9/11 and the aftermath. Following the attacks, I wasn’t very interested in getting involved in a lot of the redesign hoopla—it just seemed too soon to be thinking about rebuilding. So when this project came along roughly 15 years later, it felt like the perfect opportunity to finally contribute, particularly to the educational process of the attacks.

How did you approach the overall design?

Skolnick: We came up with some guiding principles very early on. We like to say we practiced interpretive design. We attempted to devise a theme—or really, a storyline—for the design process. It was very much about this idea of going from chaos to calm and inspiration, and going from darkness to light.

Can you elaborate on this storyline?

Skolnick: The exhibit begins with the history of downtown in a short treatment, first highlighting the settlement of Manhattan and how the island evolved into a great metropolis at the center of the financial world. Then we interrupt this narrative with the occurrence of 9/11.

We start the first gallery about the attacks themselves and the immediate impact. Everything about that gallery is jagged—there are aggressive forms, steep angles and it’s dark. It’s very disturbing—as it has to be. That darkness is punctuated by TV monitors showing some of the unsettling video footage. The spaces are also punctuated by objects—a lot of photographs, and other documentation. But then you move past that and gradually the lighting becomes brighter and the colors go from black and gray to almost a rainbow palette in the last gallery. This last space wee call the “Seeds of Service” gallery and it’s been designed to be very open and positive. It invites you to think about what you can do for your community.

The chief methodology for interpreting the story is a first-person narrative. So almost exclusively your experience is going to be that of people who were there, whether they were survivors, families of people who perished in the tragedy, first responders, firemen, Port Authority policemen, homeland security… all of these people who gave themselves and experienced traumatic loss but many of whom over time processed this horrible experience into something positive. In the “Seeds of Service” gallery you hear from people who found ways to give back to their community and to promote understanding.

But the main story we’re telling is not that of the attacks—that the purpose of the Memorial Museum down the street—rather how in this nightmare people stepped up to help other people, both in the direct aftermath and gradually over time within their communities. We wanted visitors to reflect on this and ask themselves, “What can I do? What can I do to make the world a better place? What can I do to promote peace and understanding? What can I do for my community? And beyond that, what can I do to help people in the world?”

People suffer tragedies of all sorts and there is this tendency we have to turn something negative into something even more negative. We wanted this to be a lesson in how you can overcome obstacles and challenges and do better.

Was the design process an emotional one given the gravity of what the spaces would represent?

Skolnick: It really was, particularly because we were given so many stories and many videos to watch. They were very heart-wrenching. Even the ones that resulted in positive sentiments started out as horrific situations. We tried to analyze and judge very carefully how much was enough and how much was too much. The team that worked on this was absolutely passionate about it. They are all New Yorkers, and I’m a native New Yorker, and I think together we just felt a tremendous responsibility to do this right and contribute in the only way that we felt we could. I’m very pleased with the way it turned out.

Did you speak to families of the victims or survivors to get a sense of what was wanted or expected of the space?

Skolnick: We did a lot of research on our end, but because the client had a previous venue (in the former Liberty Deli), there was a lot of existing information. We spoke to the curators who turned us onto a tremendous amount of background information. And we also had the privilege of meeting a lot of the docents and explainers who actually lived through all the events. The inspiration we felt from them when they shared their stories with us was what we wanted to deliver to visitors, and there just didn’t seem to be any other way to tell the story. We didn’t want people to be angry or upset, but like these survivors, be inspired to find ways to turn something terrible into something good.

Image © Silverstein Properties

Image © Silverstein Properties

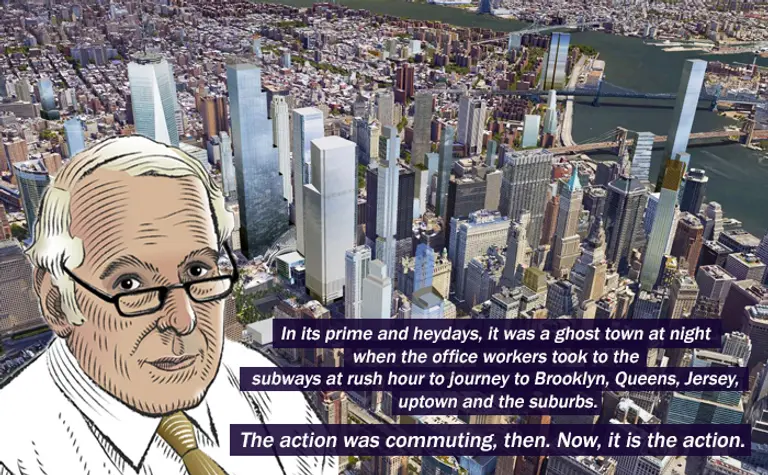

How do you feel about what’s been built on the World Trade Center site? Do you think enough has been done with the overall scheme?

Skolnick: This is a touchy subject but I’m not thrilled with what has resulted at the World Trade Center. I think that it has this feeling of “design by committee.” The overall masterplan of the buildings along the eastern edge is, from a planning point of view, a positive thing, but I think the building’s themselves are a bit lackluster. There was an opportunity to do something very dynamic and creative and I don’t think that potential was realized.

I also wish that more of the Grand Plaza, which is essentially the memorial, was developed as a civic space and not so largely as a memorial. We needed a memorial, yes, but it’s so immense that it takes up the entire plaza. I think had waited five years to rebuild it probably would have been designed differently and it would have been built as more of a community space like Madison Square or Washington Square Park. New York has so few great public spaces where people can just mingle, linger, read, talk, and find a calm oasis from the city. It would have been great if another space like that was created there.

+++

9/11 Tribute Museum

92 Greenwich Street

New York, NY 10006

(866) 737-1184

Hours:

Friday 10AM–6PM

Saturday 10AM–6PM

Sunday 10AM–5PM

Monday 10AM–6PM

Tuesday 10AM–6PM

Wednesday 10AM–6PM

Thursday 10AM–6PM

This interview has been edited and condensed

All images courtesy of the 9/11 Tribute Museum unless otherwise noted

RELATED:

- INTERVIEW: Architect Rick Cook on the legacy of COOKFOX’s sustainable design in NYC

- INTERVIEW: Paula Scher on designing the brands of New York’s most beloved institutions

- Designing One Vanderbilt: The architects of KPF discuss the incredible 1401-foot undertaking