Behind the scenes at the Loew’s Jersey City: How a 1929 Wonder Theatre was brought back to life

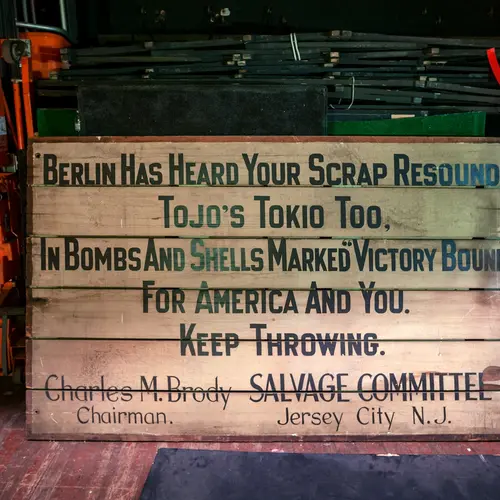

“The wealthy rub elbows with the poor — and are better for this contact,” said architect George Rapp of his Loew’s Jersey and Kings Theatres–two of the five Loew’s Wonder Theatres built in 1929-30 around the NYC area. The over-the-top, opulent movie palaces were built by the Loew’s Corporation not only to establish their stature in the film world but to be an escape for people from all walks of life. This held true during the Great Depression and World War II, but by the time the mid-60s hit and middle-class families began relocating to the suburbs where megaplexes were all the rage, the Wonder Theatres fell out of fashion.

Amazingly, though, all five still stand today, each with their own unique preservation tale and evolution. The Loew’s Jersey, located in the bustling Jersey City hub of Journal Square, has perhaps the most grassroots story. After closing in 1987, the building was slated for demolition, but a group of local residents banded together to save the historic theater. They collected 10,000 petition signatures and attended countless City Council meetings, and finally, in 1993, the city agreed to buy the theater for $325,000 and allow the newly formed Friends of the Loew’s to operate there as a nonprofit arts and entertainment center and embark on a restoration effort. Twenty-five years later, the theater is almost entirely returned to its original state and offers a robust roster of films, concerts, children’s programs, and more.

6sqft recently had the chance to take a behind-the-scenes tour of the Loew’s Jersey Theatre with executive director Colin Egan to learn about its amazing evolution and photograph its gilded beauty.

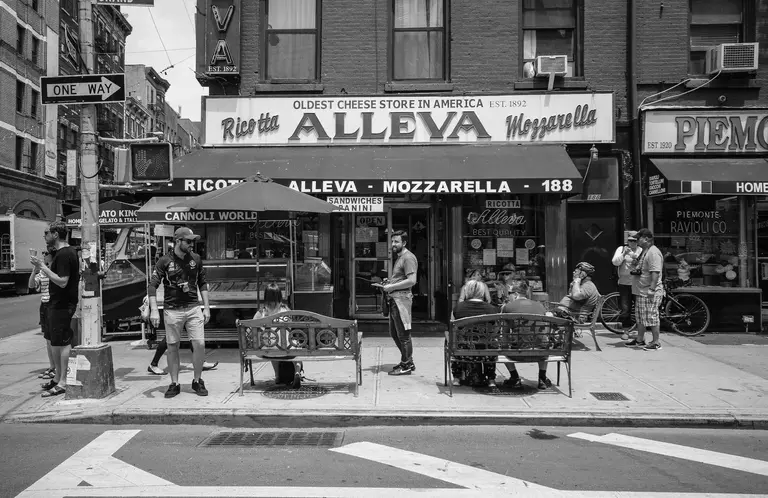

The Loew’s Jersey opened on September 28, 1929, as the fourth of the five Loew’s Wonder Theatres, just two weeks after the Loew’s Paradise in the Bronx and the Loew’s Kings in Brooklyn, both of which opened on September 7th. At this time, Journal Square was a bustling shopping and transportation district, and the location was chosen for its proximity to the train station, so celebrities from New York City could easily get across the river. It was also a hub for entertainment, as two other grand theaters–the Stanley and the State (demolished 1997)–were located nearby.

The $2 million project was designed by the Chicago-based firm Rapp and Rapp, who were considered the leading theater designers of the early 20th century, having more than 400 theaters around the country to their name. Some of their best-known works include the Chicago Theatre and Oriental Theatre in their hometown and Paramount Theatres all over the nation, including those in Brooklyn and Times Square. They also received several commissions from Loew’s, including Brooklyn’s Kings Theatre, the Loew’s State Theatre in Providence, Rhode Island, the Loew’s Penn Theatre in Pittsburgh, and the Loew’s Jersey.

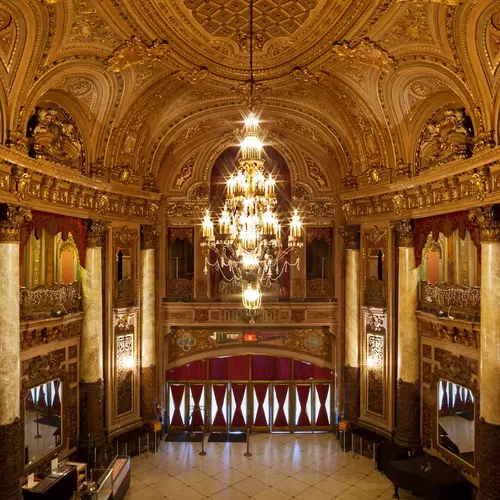

For their Journal Square masterpiece, they worked in a gilded, Baroque-Rococo style, which Egan describes as “opulence unbound but with a purpose.” The exterior was decidedly simpler, with a muted terra cotta facade and a fairly standard marquee. Two turrets frame an illuminated Seth Thomas animated clock that sits below a statue of Saint George on a horse staring down a dragon. Originally, the clock chimed every 15 minutes, which it still does today, in sync with a performance by the statues. Red bulbs in the dragon’s mouth would light up to signify fire and Saint George would tilt towards the dragon as if lunging to spear him.

The chandelier cost between $50 and $65,000 in 1929

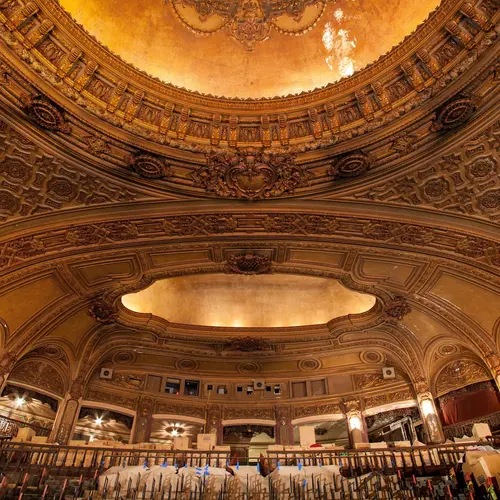

As soon as patrons entered, however, they were met with the true lavishness of the theatre. The three-story, domed oval lobby dripped in gilded ornamentation and plaster moldings, all crowned by a grand chandelier made of pre-war Czech crystal and held up by faux marble columns. According to the New York Times, “Reports of the theater opening describe an eight-foot, 150-year-old French Buhl clock, Dresden porcelain vases from the Vanderbilt mansion, bronze statues from France, crimson curtains embroidered with gold griffins and a turquoise-tiled Carrera marble fountain filled with goldfish.” Creating even more of a spectacle, guests were serenaded by live piano music or a string quartet coming from the musicians’ salon, the gallery above the entrance.

The Italian Renaissance-style auditorium boasted 1,900 seats with an additional 1,200 on the balcony. Since the stage was meant for both film and live performances, it was equipped with a full fly system attached to a 50-foot screen that could be moved in and out.

At the front of the stage, a tripartite orchestra pit was added, the left side of which held the Robert Morton “Wonder Morton” pipe organ that had 4 manuals and 23 ranks. The Robert Morton Organ Company was the second greatest producer of theatre organs behind Wurlitzer. They were known to be tonally powerful while retaining a refined, symphonic sound.

On opening night, the film “Madame X” starring Ruth Chatterton and Lewis Stone was shown along with a live musical performance by Ben Black and his Rhythm Kings and the Loew’s Symphony Orchestra. There was also a live jazz band, acrobats, comedians, and chorus girls. Tickets to the whole soiree were just 25 or 35 cents, depending on one’s seat.

Throughout the years, notable names who appeared on stage were Bob Hope, Duke Ellington, the Ritz Brothers, Jackie Coogan, and Russ Columbo and His Band. One of Egan’s favorite stories to tell is about Bing Crosby’s 1934 performance. Frank Sinatra had taken the trolley from Hoboken to catch the act, and it was then that he decided he wanted to be a singer.

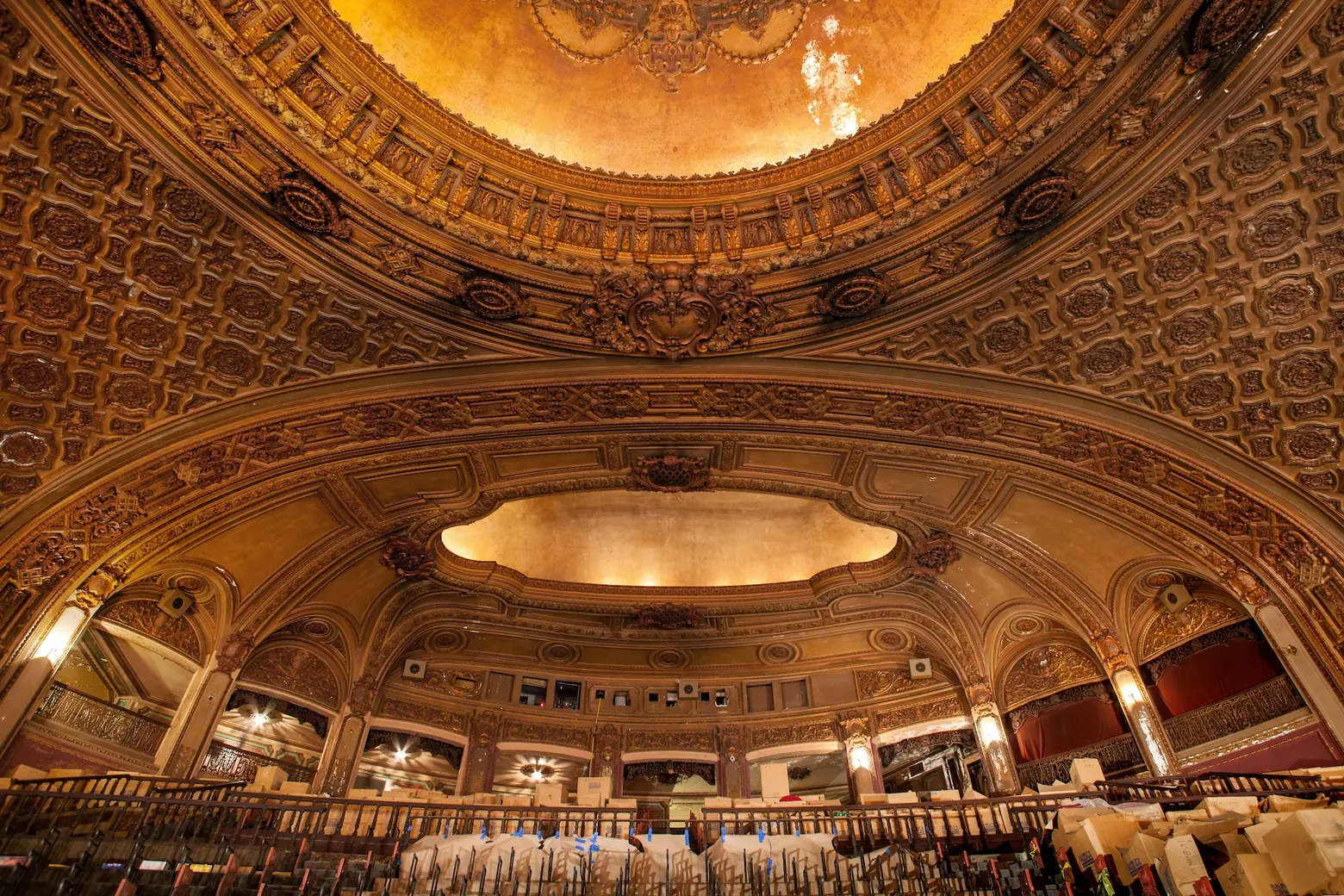

Scars of the triplexing still exist on the auditorium ceiling

Scars of the triplexing still exist on the auditorium ceiling

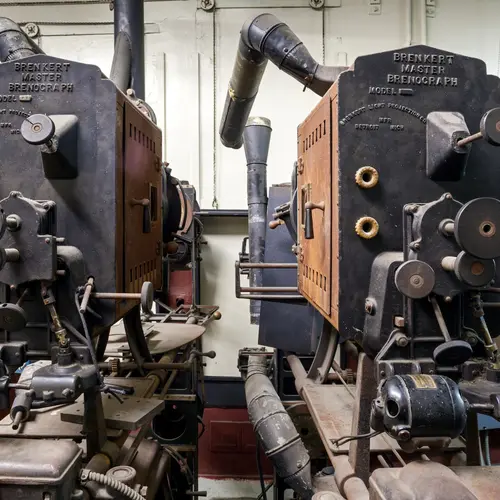

In 1974, in an attempt to compete with the influx of suburban “megaplexes,” the Loew’s Corporation triplexed the theatre. On the auditorium level, a wall was erected down the center aisle to create two smaller theaters with new projection booths. The balcony became the third theater, utilizing the original screen. It was at this time, too, that the pipe organ was removed and relocated to the Arlington Theatre in Santa Barbara, California, where it still remains.

In August of 1986, the theatre closed its door with a final screening of “Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives.” The Loew’s Corporation had sold the building to developer Hartz Mountain Industries, who planned to demolish it and replace it with an office building. But by the time the 1993 City Council hearing came around, they’d decided they no longer wanted it since they knew there would be no commercial tenants and they would spend $2 million just on demolition.

After the city acquired the building, the first thing Friends of the Loew’s did was submit a $1 million grant to the state for stabilization (basically, patching the roof and facade to make sure it didn’t deteriorate any further), The city agreed to match the grant, but they failed in their promise to help in the process of raising the additional funds needed to get the theater up and operational, as that initial $2 million didn’t cover the cost of things such as getting the heat turned on and making the bathrooms operational. (To give a point of comparison, the entire restoration of the Loew’s Kings Theatre in Brooklyn cost $95 million).

The seat cushions were so moldy, volunteers had to wear respirators at first

The seat cushions were so moldy, volunteers had to wear respirators at first

At this point, Friends feared the project was “dead in the water,” according to Egan. “The only out that any of us could think of was to ask all the folks who had come out to meetings, and signed, and worked with us to roll up their sleeves and try to do some work,” he said, adding that there was a part of him that thought the plan was “too fantastical.”

A balcony-level view of a yet-to-be-restored area and seats that still need to be worked on

A balcony-level view of a yet-to-be-restored area and seats that still need to be worked on

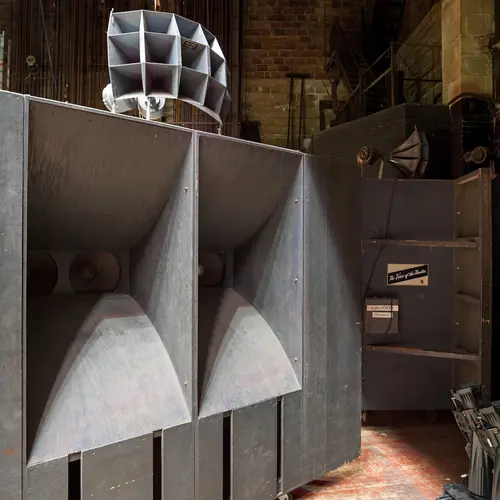

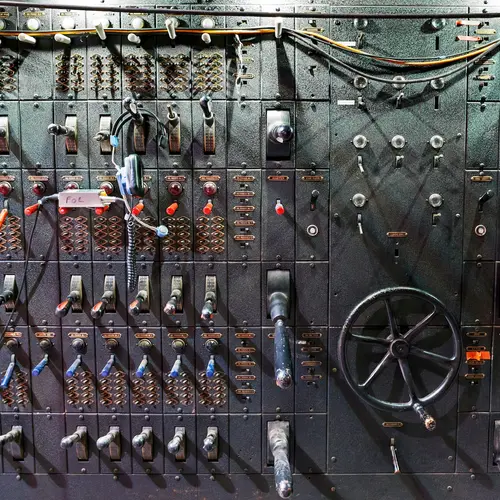

But Egan is now happy to say he was wrong. Every weekend from that point to 1996, volunteers were working in the theater. They removed the partitions that had been put up, worked on the mechanical, lighting, and stage systems, and updated the original projection equipment and added modern versions. They also stripped layers upon layers of paint from the marble fixtures in the bathrooms and removed pigeon coops from the projection booth.

One of the biggest jobs was the seating. Volunteers mapped every seat–they’re slightly different sizes depending on what part of the curve they’re located on–before removing them, scraping the old paint, priming and painting all the metal, staining and varnishing the armrests, and adding new ball bearings.

The organ arrived from California in two tractor-trailer loads of parts

The organ arrived from California in two tractor-trailer loads of parts

In addition, the Garden State Theatre Organ Society donated a new organ. It wasn’t the original, but it was the one that had been at the Loew’s Paradise in the Bronx. It took 11 years of restoration work by Society volunteers to get the instrument up and running in 2007. This included putting back 1,800 pipes, the platform, and all the wires. It’s now the only Wonder Morton Organ still in use at a Wonder Theater.

The first truly public event took place at the end of 2001–a tribute to the anniversary of Pearl Harbor and a memorial to the then very recent September 11th attacks. Today, the Loew’s Jersey Theatre puts on 70 events per year (they still don’t have air conditioning, so can’t operate in the summer). It’s the only wonder palace still showing films, as well as concerts, children’s programs, and musicals and plays. They also rent out the space for private events like weddings. Just as George Rapp described it in 1929, the theatre is once again “a shrine to democracy where there are no privileged patrons.”

Though it may not look like it from the photos, there is still work to be done at the Loew’s Jersey Theatre. For example, the building doesn’t have air conditioning and therefore can’t operate in the summer. Egan estimates this will cost $1.5 million. And the fire system isn’t fully up to code yet, so for every event a fire marshall must be present. Find out how to get involved with the preservation efforts and check out the current roster of events here >>

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

I grew up in Jersey City and lived there for the first 22 of my 52 years. Needless to say, the Lowe’s Jersey was a place that bore many memories for me. It was there that I dated a couple of girls I asked to marry and fell in love with films and film making… I went on to become a special effects artist for that reason.

I’ve moved away but still occasionally make the trip back to this theater to see films that have special meaning for me and am enormously grateful to the Friends of Lowe’s who saved this marvelous place… so grateful in fact that I each time I visit, I’m near tears.

There’s one reason and one reason only for Friends of Lowe’s to have committed to their tireless efforts and that reason is LOVE. I could take the time to write many qualifiers to that statement but at it’s core the reason is just that, LOVE.