10 things you might not know about the Statue of Liberty

Photo © James and Karla Murray for 6sqft

The debate around American immigration policy has become so contentious and dispiriting that the acting director of US Citizenship and Immigration Services has actually suggested amending “The New Colossus,” Emma Lazarus’ immortal words of welcome inscribed on the base of the Statue of Liberty. But at the same time, writer Joan Marans Dim and artist Antonio Masi have brought out “Lady Liberty: An Illustrated History of America’s Most Storied Woman.”

After getting a sneak peek of the new book, it seemed timely to take a deep dive into the history of the Statue of Liberty, which represents not only our city but one of the most vital and necessary of all American values. Ahead, discover 10 things you might not know about the Statue of Liberty, from its beginnings on “Love Island” to early suffragette protests to its sister in Paris.

1. Liberty Island was once called Bedloe’s Island

Today, we call the home of the Statue of Liberty “Liberty Island.” But before it was named for the Lady, it was named for a man. Isaac Bedloe bought the island in 1667. By the 1750s, Bedloe’s Island was also sometimes referred to as “Love Island.” At the time, the island sported a home and lighthouse and was said to “abound” with rabbits.

By 1800, the island actually became a defensive fortification in New York Harbor. The 11-point star-shaped structure that is now part of the base of the Statue of Liberty was actually built as a fort. It was completed in 1811, just in time for the war of 1812. Even when Bedloe’s Island became home to the Statue of Liberty in 1886, the name didn’t change. It wasn’t until 1956 that the site of the statue officially became “Liberty Island.”

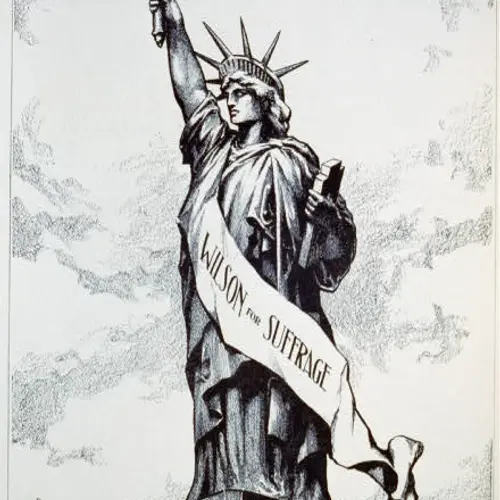

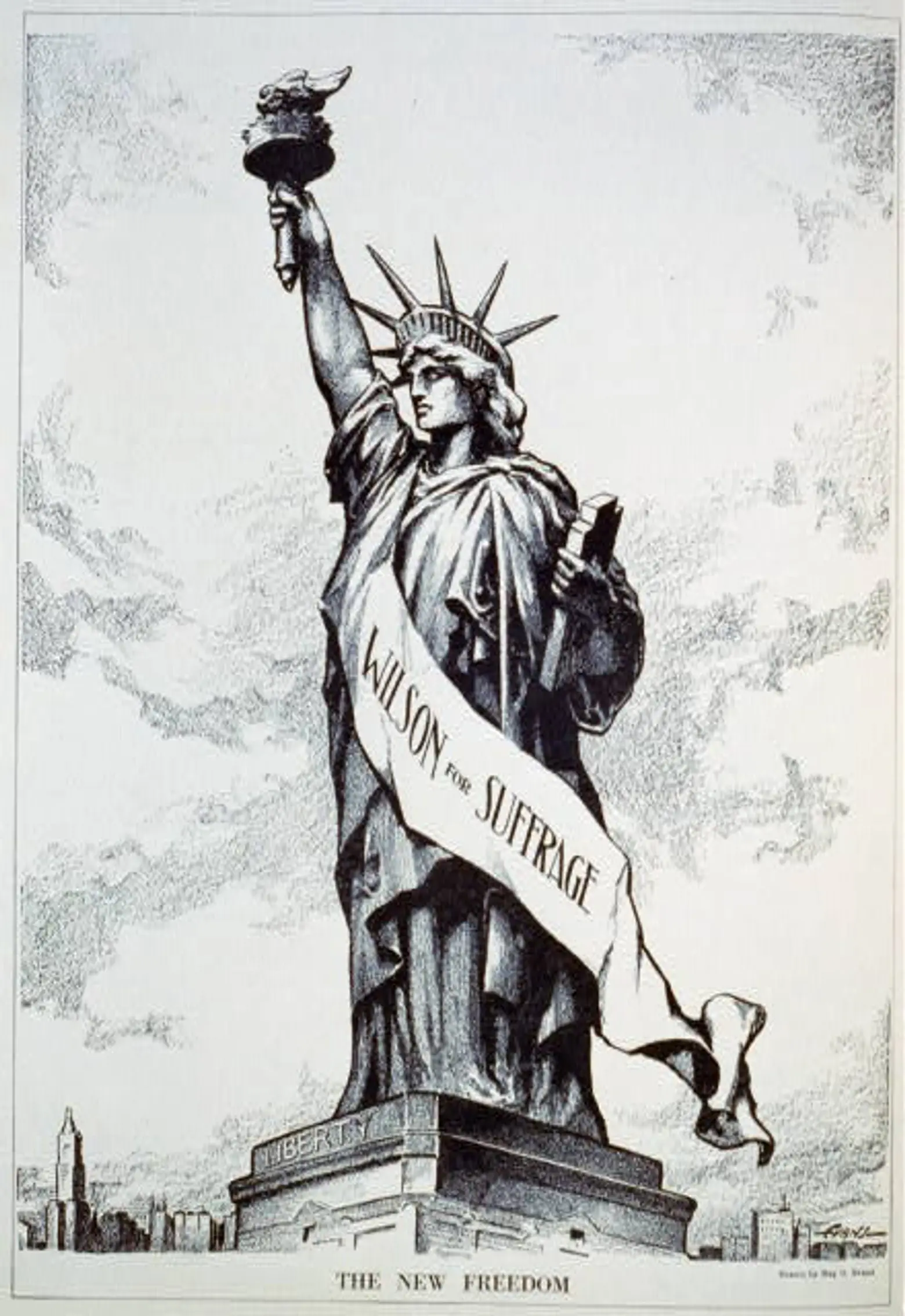

Cartoon from a 1915 issue of Puck Magazine via The Library of Congress

Cartoon from a 1915 issue of Puck Magazine via The Library of Congress

2. Suffragettes protested the dedication of the Statue of Liberty

Whose liberty? That was the question on the mind of members of the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association on the morning of October 27, 1886 – the day before the statue’s dedication. That day, about 60 suffrage advocates, led by Lillie Devereux Blake, drafted a resolution stating that the Statue of Liberty “points afresh to the cruelty of woman’s present position, since it is proposed to represent Freedom as a majestic female form in a State where not one woman is free,” because not one woman could vote. The next day, during the Statue’s dedication, Blake and co. rented a barge in New York harbor and covered it with protest banners in order to draw attention to the hypocrisy of celebrating female liberty in name only.

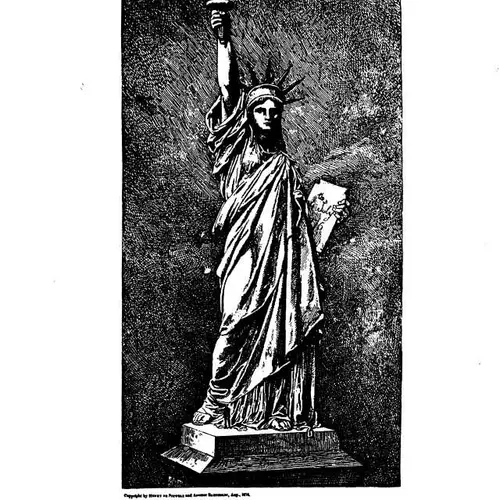

Illustration from Lady Liberty: An Illustrated History of America’s Most Storied Woman, by Antonio Masi, courtesy of Antonio Masi

3. Poetry by Emma Lazarus, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman was sold at auction to help finance the statue’s pedestal

Since the Statue of Liberty is an enduring American symbol of freedom and tolerance, it makes perfect sense that writers like Walt Whitman, the father of Free Verse, and Mark Twain, the great chronicler of 19th-century American morals, would donate their work to help fund the statue’s construction.

By 1883, France had already gifted the Statue of Liberty to the United States on the condition that the U.S. would fund the construction of the statue’s foundation and pedestal. That year, Emma Lazarus was 34 years old and already a renowned poet within the small and elite circle of New York artists and writers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson who knew and admired her work. Accordingly, the New York literati asked Lazarus is she would compose a sonnet to be sold at auction alongside works by Twain and Whitman in support of the statue. That sonnet was “The New Colossus.”

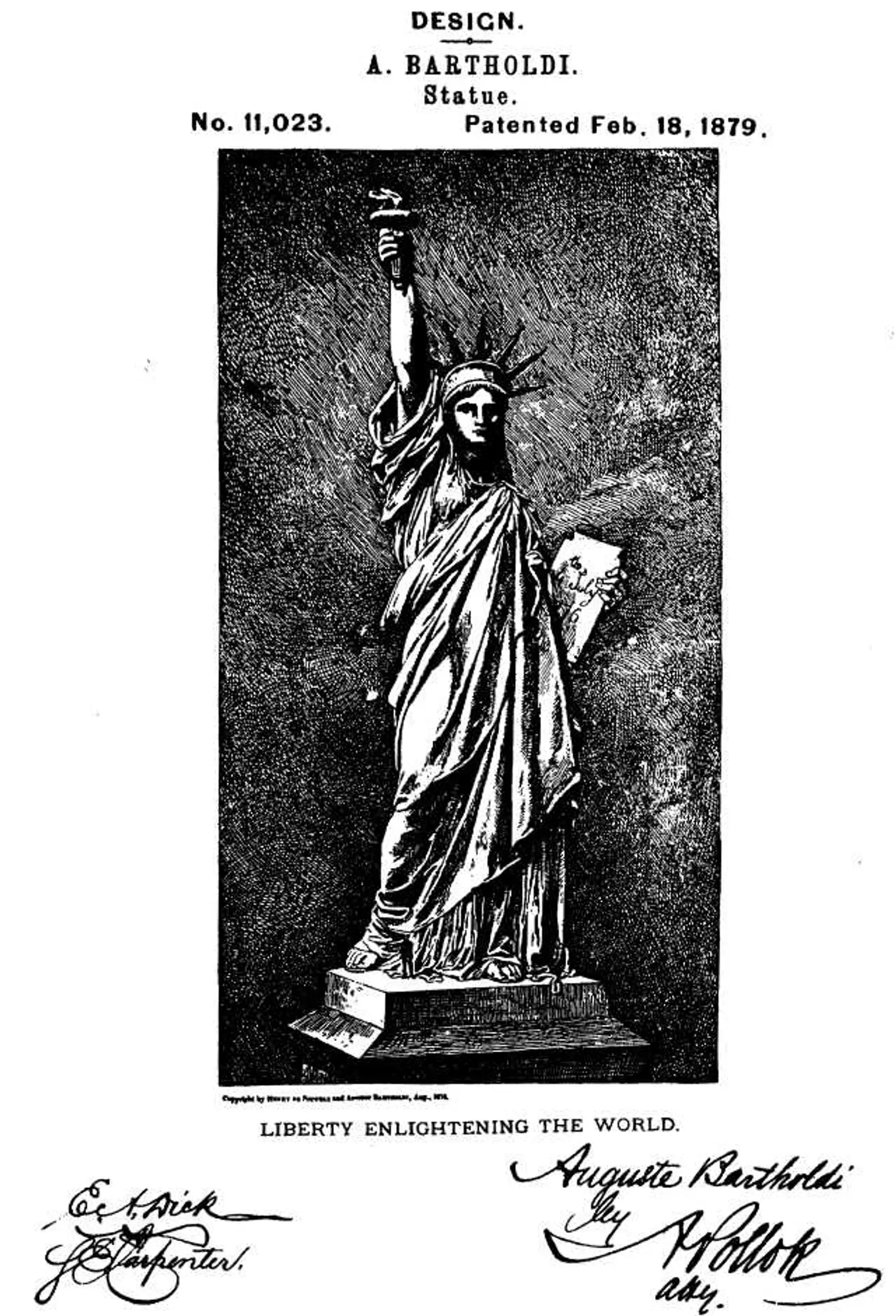

Bartholdi’s design patent for the Statue of Liberty via Wikimedia Commons

4. Bartholdi’s design for the statue was based on his rejected proposal for a lighthouse at the Suez Canal

There are many wonderful stories of rejected proposals or unrealized ideas taking new shape in even more spectacular and dynamic ways. For example, Frank Lloyd Wright based his idea for the Guggenheim on an unrealized design for a salad bowl. The Statue of Liberty is one such story. Lady Liberty was not Frederic Auguste Bartholdi’s first attempt at creating a colossal goddess. In 1869, Bartholdi went to Egypt to pitch his lighthouse idea to the Egyptian leader Khedive Ismail.

Bartholdi’s sketches for his proposed lighthouse at the Suez Canal show a woman holding a torch. She is meant to represent “Progress, or Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia.” Ultimately, Khedive Ismail turned Bartholdi down because the statue was cost-prohibitive. In fact, New York City almost lost the Statue of Liberty for the same reason…

The Arm and Torch of The Statue of Liberty at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition via Wikimedia Commons

5. Philly tried to snag the statue

Bartholdi might have been passionate about his statue, but in the late 1870s, fundraising dragged for the pedestal. By May 1876, Bartholdi had taken to showing off part of the statue around the United States to drum up support for the project. At the time, the Statue’s right arm, including the torch, was on display at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition – and the city liked it there. Philadelphia offered to finance the statue if Bartholdi agreed to erect it there. Ultimately, Pulitzer got the prize…

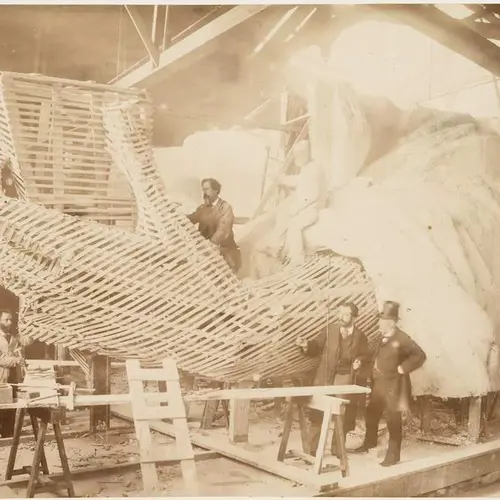

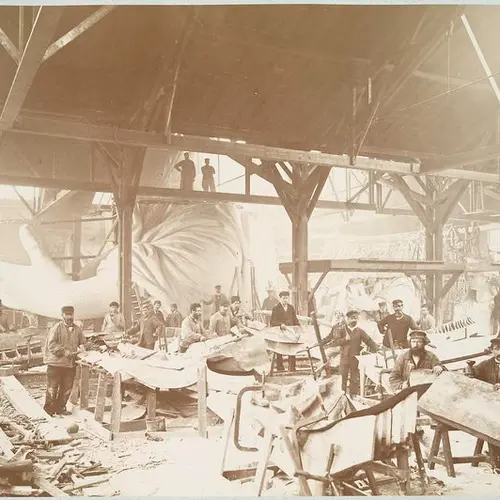

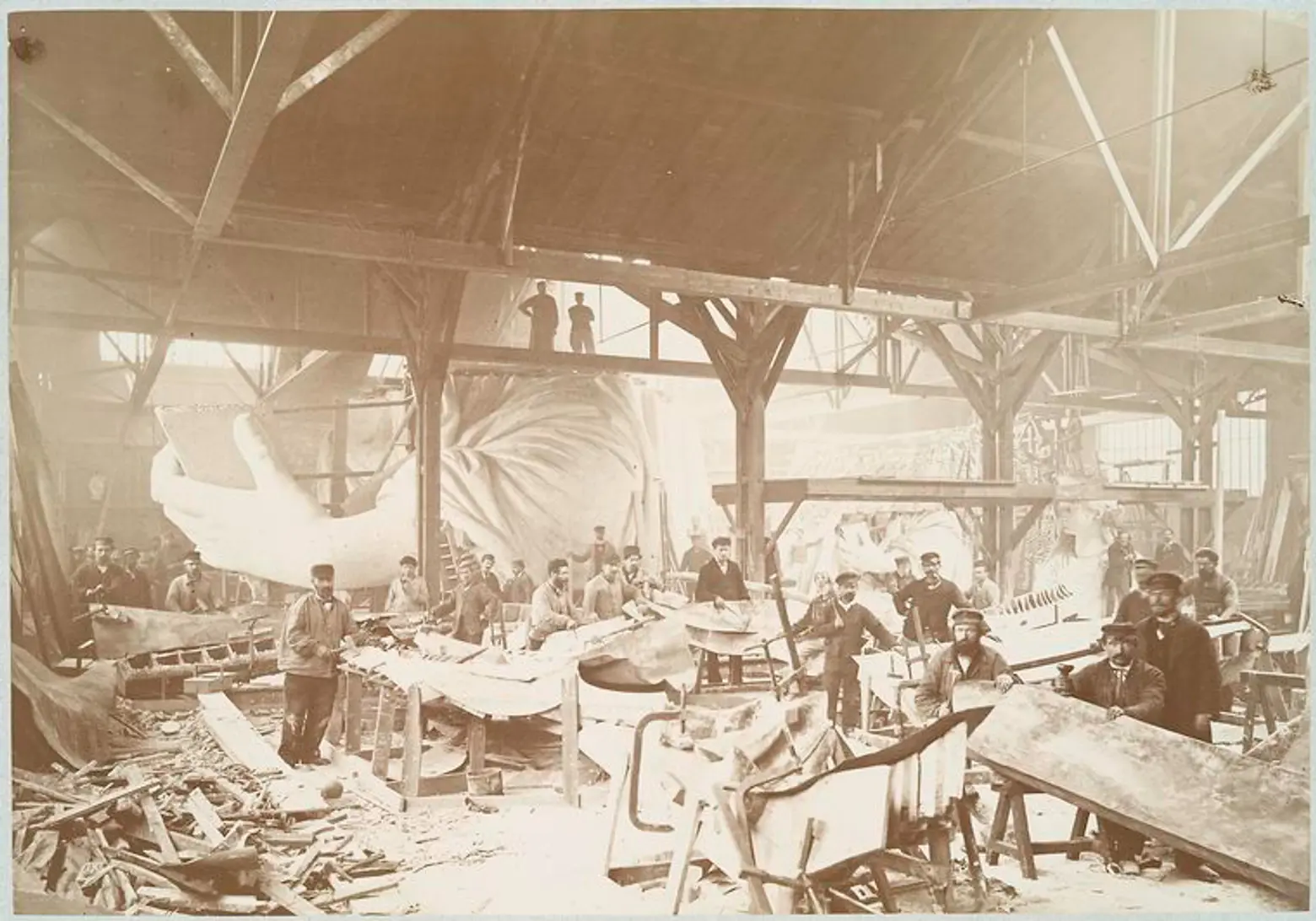

Men in a workshop hammering sheets of copper for the construction of the Statue of Liberty, 1883, via NYPL Digital Collections

6. The Statue of Liberty was World famous before it was even built

Pulitzer himself was a Hungarian-born immigrant. Raising funds for the Statue of Liberty appealed to him. He used his newspaper, The New York World, as a platform to solicit donations. Pulitzer announced from the World’s editorial pages that he would publish the name of any person who made a contribution to the Statue of Liberty, no matter how small the sum. He appealed “to the whole people of America,” to make a donation to the pedestal fund. He noted, in words that land hard today, Liberty “is not a gift from the Millionaires of France to the Millionaires of America,” but instead an international project of “the whole people.” The campaign was a major success. In a few months, Pulitzer raised $100,000 (nearly $2 million today) from donations of a dollar or less.

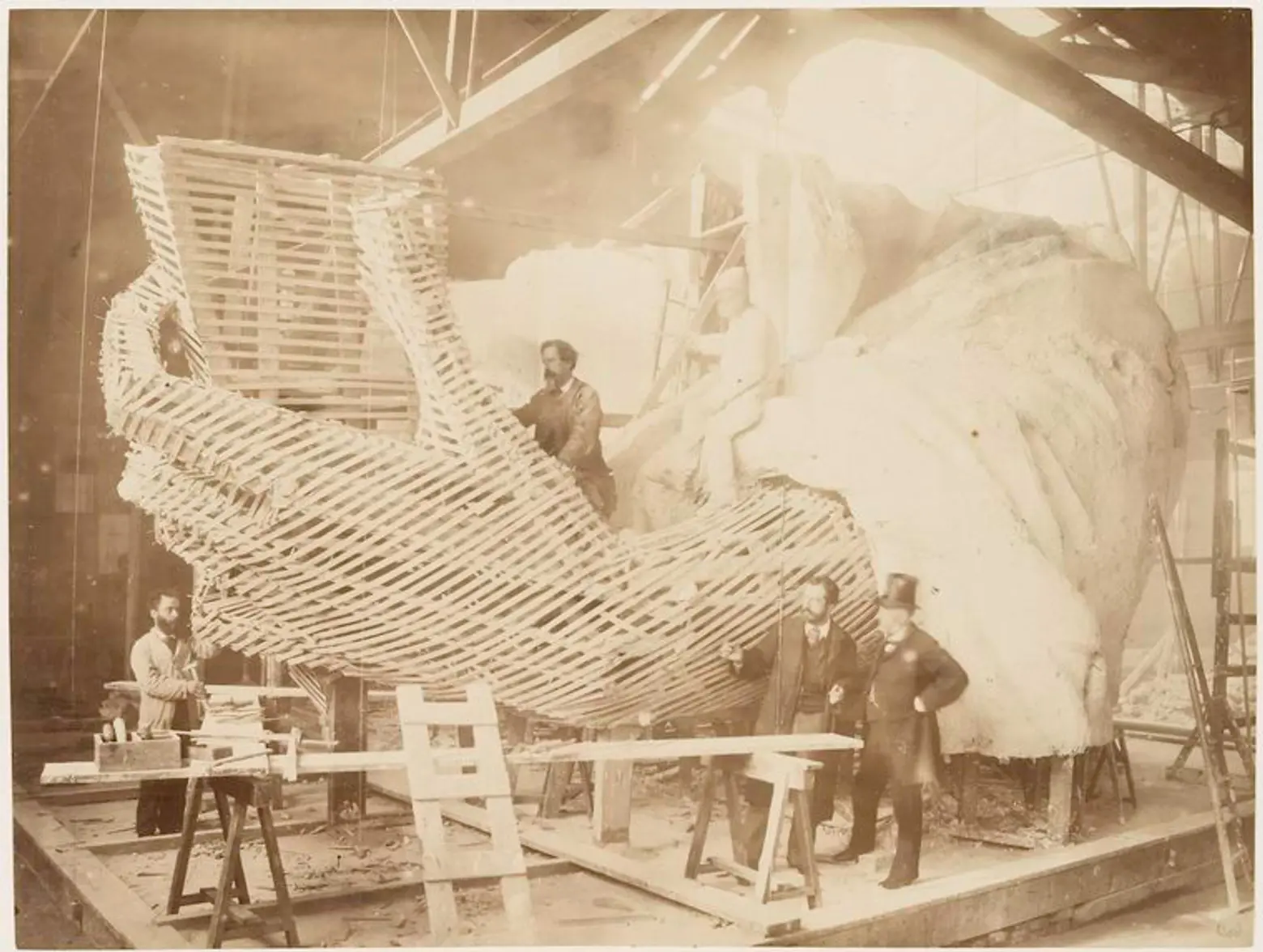

Construction of the skeleton and plaster surface of the left arm and hand of the Statue of Liberty, 1883, via NYPL Digital Collections

7. Designing and building the statue was a major political statement in late-19th-century France

The Statue of Liberty was a celebration of the American ideal, but it was conceived and planned in France during the repressive reign of Napoleon III. During Napoleon III’s Second Empire, crafting a Statue of Liberty was a direct repudiation of the government and could lead to imprisonment.

Illustration from Lady Liberty by Antonio Masi, courtesy of Antonio Masi

8. The Statue of Liberty was once the tallest structure in New York City.

From the pedestal’s foundation to the tip of Liberty’s torch, the structure stands 305’1”. That’s equivalent to a 22-story building, which was unprecedented in 1886 when the statue was dedicated. At the time, Lady Liberty towered over the city as its tallest structure, even eclipsing the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Liberty on the Seine via Wikimedia Commons

9. The French loved the statue so much, Bartholdi built a replica to keep in Paris.

If you find yourself sailing along the Seine, you’ll see a ¼-size replica of the Statue of Liberty, built by Bartholdi and financed by the American community in Paris, as a gift to the French people.

Illustration from Lady Liberty by Antonio Masi courtesy by Antonio Masi

10. “The New Colossus” was not inscribed on the Statue’s base until 1903 (and you can thank a descendant of the Schuyler Sisters)

Emma Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus” in 1883. She died of Lymphoma in 1887, when she was just 38. Fourteen years later, in 1901, Lazarus’s friend Georgina Schuyler rediscovered the poem in a volume at a used bookstore. Moved by the work, Schuyler mounted a civic campaign to have its words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty. The campaign succeeded in May 1903, and those words have been a symbol of welcome and beneficence ever since.

To learn more about the Statue of Liberty’s history, you can visit the recently opened Statue of Liberty Museum.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.