10 offbeat haunted spots in New York City

St. Paul’s Chapel via Flickr cc

‘Tis the season to voluntarily spook yourself! But if haunted houses and tourist-friendly ghost tours are not for you, New York’s bustling burrows are home to a slew of the more naturally born spirits. You’ll find Dracula’s extended family on 23rd Street, a host of oracles on Orchard Street, and the site of the cruel crime that led to the nation’s first recorded murder trial on Spring Street. If you’re searching for a necropolis in the metropolis, here are ten of the best sites in New York to spot specters.

St. Marks Church in the Bowery (L) via Wiki Commons; Bust of Stuyvesant via Wiki Commons (R)

1. St. Marks Church in the Bowery

New York’s original ghost might be Peter Stuyvesant, the last governor-general of New Amsterdam. Peg-leg Pete died in 1672 and is interred in a vault beneath St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, which was built on the Stuyvesant family farm in 1799. According to the New York Times, Peter get-off-my-lawn Stuyvesant was aggrieved by the city’s growth northward onto his farmland and was known to come from beyond the grave to register noise complaints. Local lore holds that shortly after his death, when Stuyvesant was disturbed from his slumber by the bustle of the growing city, he responded in kind, making a racket with the church bells.

St. Paul’s Chapel in Manhattan, one of only a few structures left on the island built before 1776. Photo credit: eviltomthai cc

2. St. Paul’s Chapel

Stuyvesant isn’t New York’s only churchyard terror. In fact, St. Paul’s Chapel is stalked by a headless thespian. George Fredrick Cooke had once been the greatest Shakespearean actor of his generation. His portrayal of Richard III at the Covent Garden Theater in 1800 was hailed as a triumph. In addition to his talent, Cooke’s life was marked by serious addiction. He struggled with alcoholism and died of cirrhosis while on a tour of New York in 1812. After his burial at St. Paul’s Chapel, Cooke’s life got truly dramatic. He had willed his head to science in order to pay his medical bills and was decapitated post-mortem. What became of his cranium is subject to rumor, but the best one is that Cooke’s skull had its own career on the stage, having been used as Yorick in productions of Hamlet at the Park Theater in New York.

129 Spring Street; Photo by Beyond My Ken on Wikimedia

3. The Manhattan Well

Modern theater fans and history buffs on the hunt for Alexander Hamilton often find their way to his grave at Trinity Church. But those looking for a more ghoulish episode in Hamilton’s life may want to head over to 129 Spring Street, home of the Manhattan Well. A foul felony at this Well led to the nation’s first recorded murder trial, featuring Hamilton and Aaron Burr both arguing in defense of the accused. On December 22, 1799, Gulielma “Elma” Sands snuck out of her boarding house at 208 Greenwich Street with plans to elope with her fellow boarder Levi Weeks. On January 2, 1800, Elma’s body was found at the bottom of the Manhattan Well. Weeks was arrested and charged with her murder, but wealth and connection bought him the services of both Hamilton and Burr. During a two-day trial that stunned the city, he was acquitted after just five minutes of jury deliberation. Public opinion stood staunchly against Weeks, and he skipped town, landing in Mississippi, where he became an architect.

Poe Cottage; Photo by JHSmithArch on Wikimedia

4. Poe Cottage

Speaking of spooky firsts, Edgar Allan Poe is considered the nation’s first lyric poet and the father of the modern detective story. The master of the macabre was also a New Yorker. It was here he wandered weak and weary, penning classics including “The Raven” and “Annabel Lee.” Poe’s peregrinations took him all over New York. He lived on Greenwich Street, Ann Street, Waverly Place, Carmine Street, East Broadway, Amity Street (now West 3rd Street), and Brennan’s Farm (Now 84th Street and Riverside Park). But his most permanent residence in the city was in the Bronx at Poe Cottage, where he lived for the last three years of his life. Today, Poe Cottage is a national historic landmark and the only writer’s house open to the public in New York City.

Photo via Wiki Commons

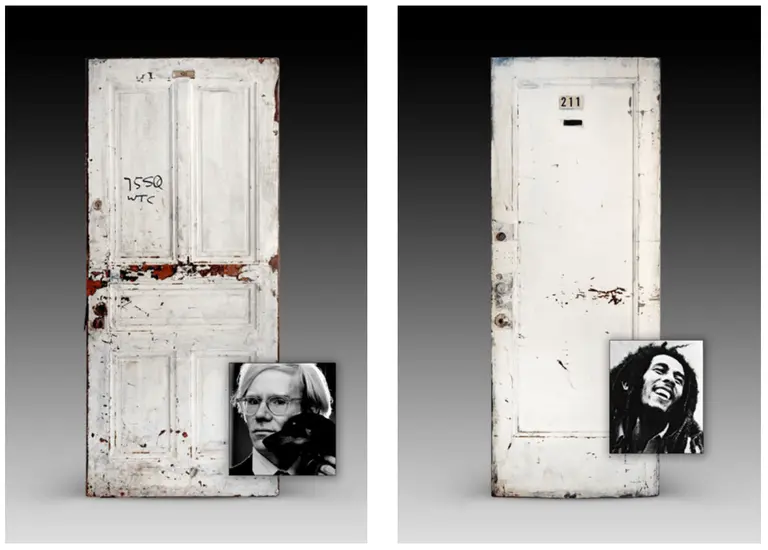

5. The Chelsea Hotel

Chelsea Girls? More like Chelsea ghosts. The Chelsea Hotel, the shabby-chic abode at 222 West 23rd Street, reigned for over a century as the legendary home of artists and writers until it was closed for redevelopment in 2011. The specter of genius stalks the halls: it was here that Andy Warhol made Chelsea Girls, Robert Mapplethorpe photographed Patti Smith, Arthur Miller wrote “After the Fall,” Arthur C. Clarke produced “2001 – A Space Odyssey,” and William Burroughs penned “Naked Lunch.” It was here, too, that Sid stabbed Nancy, and Dylan Thomas went gentle into that Good Night.

You’d have to go into the apartments to find the artists, but you could find vampires in the lobby. The poet and biographer Ulick O’Connor was standing at reception one evening when he was introduced to Count Roderick Gheka, the son of the Crown prince of Romania, and a direct descendent of Count Vlad, best known as Dracula. O’Connor told The New York Times, “‘the funny thing was, when I talked to him, I found out his mother was Maureen O’Connor, a distant relative of my father.'” Citing this episode of madcap genealogy, O’Connor captured the zeitgeist of the hotel: “The Chelsea Hotel is the only place in the world where you can meet Dracula’s Cousin and he turns out to be your cousin, too.”

The Smallpox Hospital today, via Wiki Commons

The Smallpox Hospital today, via Wiki Commons

6. Roosevelt Island

Roosevelt Island was originally known as Blackwell’s Island and was eventually nicknamed “Welfare Island.” Sporting both an abandoned smallpox hospital, and a former insane asylum, Roosevelt Island has a rich and sorted spooky history.

The Smallpox Hospital served victims of “that loathsome malady” from 1856-1886. By 1871, the disease had reached endemic proportions in New York and disproportionately affected recent immigrants. Due to the contagious nature of the disease, and nativist fears surrounding immigrants, smallpox victims were tightly quarantined on Blackwell’s Island.

The island’s second site of suffering is the Octagon. Now part of a residential building, it opened in 1839 as the New York City Lunatic Asylum, the city’s first municipal mental institution. Patients faced conditions so abysmal that journalist Nellie Bly referred to the place as “a human rat-trap” in her 1887 expose, “Ten Days in a Mad-House.” The book, originally published as a series of articles in The New York World, helped change the way Americans viewed mental healthcare.

Via Wiki Commons

7. Washington Square Park

Before it was a park, Washington Square was a potter’s field. Today, there are at least 20,000 people buried under the Square, and they come up for air every so often. Washington Square was used for public hangings and pauper’s funerals until 1823. Con-Ed workers excavating a site in Washington Square in 1965 encountered what the New York Times called, “a room full of bodies” containing at least 25 skeletons. In 2015, workers laying a water main along Washington Square East hit upon two vaults covered in dozens of coffins. This past March, the city’s Parks Department reinterred the human remains and added an engraved paver to mark the site.

Photo credit: Hal Hirshorn

8. The Merchants House Museum

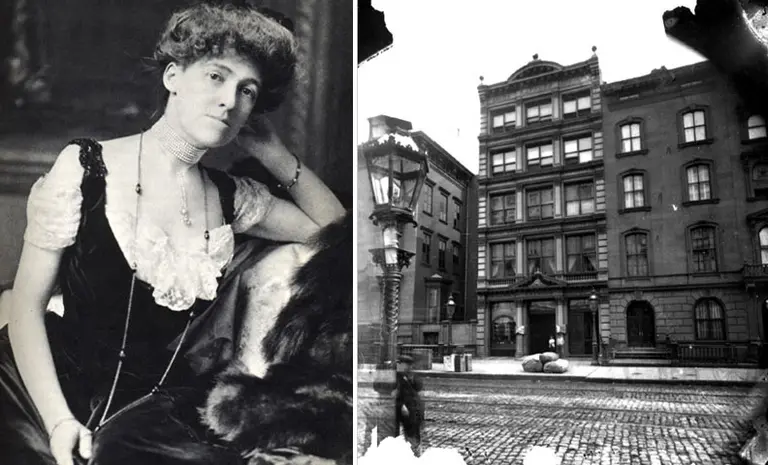

The Merchant’s House Museum at 29 East 4th Street is a lovingly preserved example of Gaslight New York. It was one of the first buildings in New York to be designated a landmark and is the only family home in New York City to survive intact from the 19th century, with its original furniture, decorative arts, and family heirlooms. Wealthy merchant Seabury Treadwell bought the home in 1835 when East 4th street was one of the most illustrious addresses in New York, and the Treadwell family lived there for nearly 100 years. Only three of Seabury and Eliza Treadwell’s eight children married, and three of the Treadwell sisters lived their entire lives in the house. The Museum claims they never left. The youngest, Gertrude Treadwell, was born in the house in 1840 and died there in 1933. Her home became a museum in 1936 and was landmarked in 1965.

Photo via CityRealty

Photo via CityRealty

9. The Tenement Museum

The Tenement Museum preserves and celebrates the immigrant history of the Lower East Side. One of the many newly-arrived New Yorkers who lived or worked at 97 Orchard Street at the turn of the 20th century was the “World Famous Palmist and Mind Reader,” Professor Dora Meltzer. Professor Meltzer’s advertisement claimed, in both Yiddish and English, that she could see “the past, present and future,” and if one came to the first floor back room of 97 Orchard Street with 15 cents, she would dispense “the best advice in business, journeys, law suits, love, sickness, family affairs etc.”

Meltzer was not the only oracle of Orchard Street. Fortune telling was a popular pastime among Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side. Drawing on ancient Jewish mysticism, and a host of old-world superstitions, the immigrant psychics could offer advice and social support to neighbors struggling with new lives in America, while also earning a little bit of extra money to help alleviate the grinding poverty of tenement life. In fact, Abraham Hochman, who was recorded in the 1910 census as a “mind reader,” became Tammany Hall’s official psychic, and was known as “the richest man on Rivington Street.”

Photo by Beyond My Ken on Wikimedia

10. Bloody Angle

Nearby, on Doyers Street, murder and mayhem reached unprecedented heights. Today, Doyers Street is a pedestrian thoroughfare boasting both the oldest dim sum restaurant in the city, and newly appointed artisanal speakeasies, but at the turn of the 20th century, it was a much more grisly scene. At that time, Doyers Street was the center of territorial warfare between rival Tongs, or gangs. The situation was so volatile, the NYPD has claimed that more people have died violently at “Bloody Angle,” at the center of Doyers Street, than at any other intersection in America.

Editor’s note 10/25/21: A version of this post was originally published on October 17, 2018.

RELATED:

- How a Greenwich Village brownstone became known as the ‘House of Death’

- All of the spooktacular events coming to the Merchant’s House Museum this Halloween

- Go ghost hunting at Mark Twain’s haunted and historic Connecticut manor

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Thanks for sharing!