New-York Historical Society exhibit looks back at NYC’s lost landmarks

Unidentified photographer, Manhattan: the Hippodrome, Sixth Avenue between, 43rd Street and 44th Street, 1905. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

A new installation at the New-York Historical Society explores the forgotten places that once defined New York City. The installation, called “Lost New York,” brings to life the city’s lost landmarks, including the original Penn Station, the Croton Reservoir, the Chinese Theater, and river bathhouses, through more than 90 items from the museum’s collections and first-hand accounts from community voices. On view from April 19 through September 29, the museum is launching a new pay-as-you-wish program on Friday evenings from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. to coincide with the new exhibition.

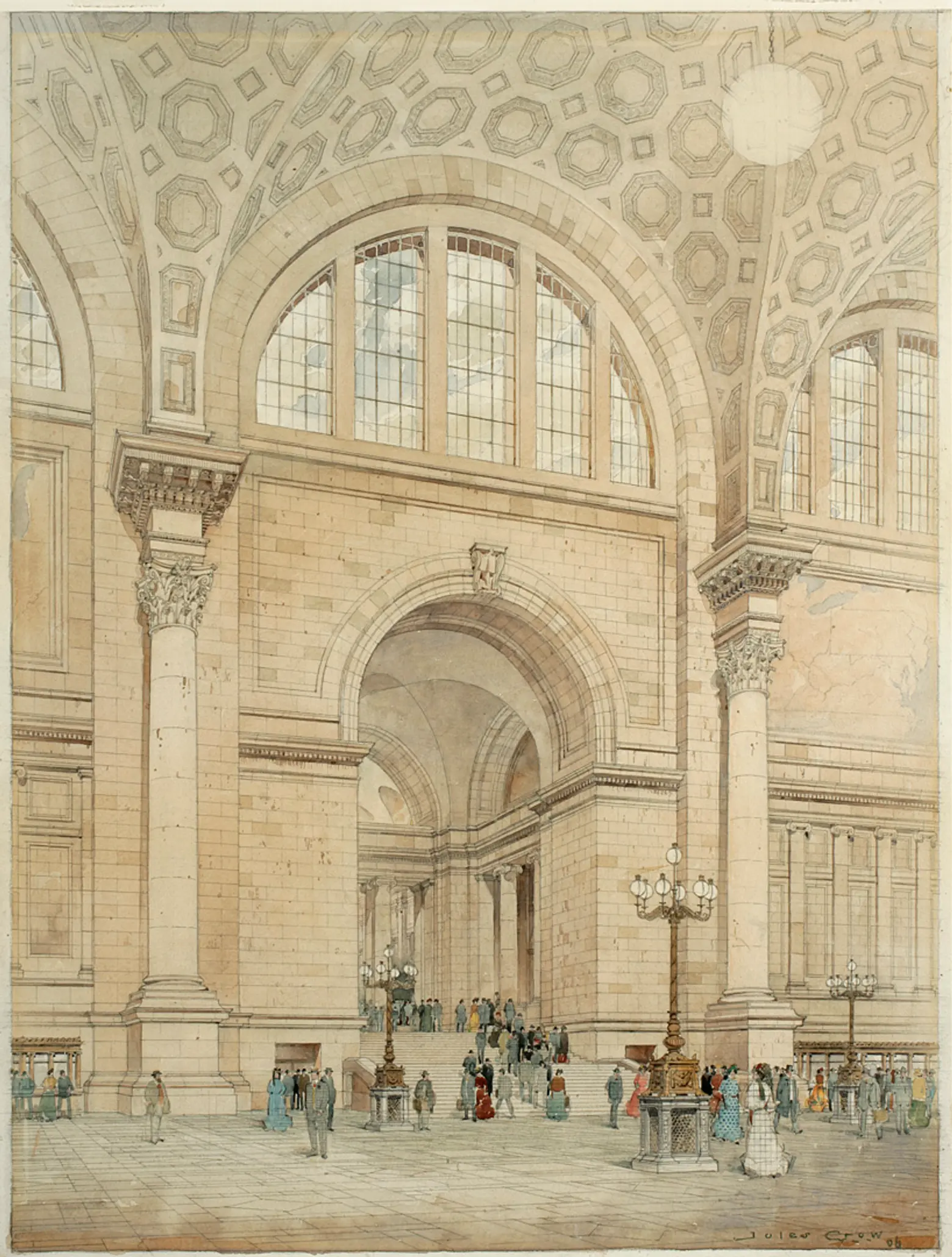

The exhibition features more than 90 paintings, photographs, objects, and lithographs that offer a glimpse into the city’s past. Included in the exhibition is Jules Crow’s depiction of the original Penn Station’s interior in 1906.

Designed by McKim, Mead, and White and opened in 1910, the building only stood for 54 years before it was demolished. The razing of such a beloved architectural landmark spurred the creation of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission two years later.

Another featured landmark is New York’s Crystal Palace, captured in François Courtin’s lithograph during the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. Situated in what is now Bryant Park, the architectural marvel was once the largest building in the Western Hemisphere and hosted technological innovations from across the globe.

The original Croton Reservoir, constructed to increase the city’s water supply, is depicted in an 1850 lithograph by Charles Autenrieth. The reservoir’s massive Egyptian-style walls became a popular promenade spot for New Yorkers. Parts of the original structure can still be seen on the lower level of the New York Public Library on 42nd Street.

An 1837 oil on wood panel painting by sign painter De La Prelette Wriley depicts his business located at 7 1/2 Bowery while also providing a look at what the surrounding area would look like on a typical day. Men, women, children, and horses & carriages go on about their day, while a pig lingers in the street.

Pigs, low-maintenance and a good source of protein, according to the museum, were commonly seen wandering through the city until 1859. The animal also served as the city’s “first” crude garbage management system, eating scraps off the ground.

Accompanying many of the featured works are observations from New Yorkers sharing their memories of the locations depicted. These voices include an LGBTQ+ artist who purchased a t-shirt from Keith Haring’s Pop Shop and a woman in a family of Yankees fans who remembers watching David Wells and David Cone pitch perfect games.

“‘Lost New York’ delves into the many and deep layers of this city. I hope visitors will delight in discovering the landmarks that once defined the places they know but also consider the serious issues, like gentrification and environmental devastation, that drove their loss and reflect upon the importance of preserving our past,” Dr. Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto said.

“It has been an honor to connect with members of our community and learn about their experiences with these lost places. Their voices enliven and personalize the exhibition and sustain the memory and meaning of these sites.”

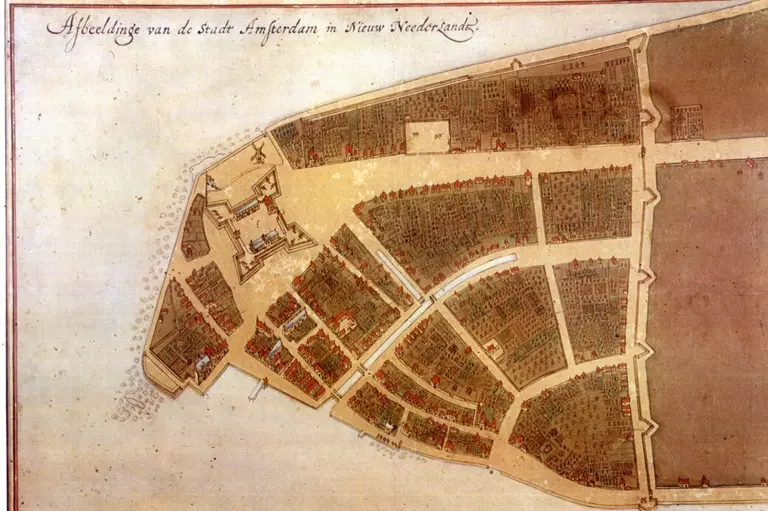

Also on view at the New-York Historical Society is “New York Before New York: The Castello Plan of New Amsterdam,” an installation centered around the Castello Plan, a historic map depicting New Amsterdam in 1660 right before the English took control. On view through July 14, the installation also features rare documents and objects exploring the lives of settlers, Indigenous people, and enslaved Africans who resided in the colony.

Coinciding with the launch of “Lost New York,” the Society is starting a pay-as-you-wish on May 3 and continuing through early summer. Starting at 5 p.m. and lasting until 8 p.m., the admission model and expanded hours will also feature a live band playing classic jazz and American standards, and a bar offering classic and forgotten NYC cocktails.

RELATED: