Where I Work: The Four Freedoms Park team talks Louis Kahn, FDR, and preserving a legacy

As a media sponsor of Archtober–NYC’s annual month-long architecture and design festival of tours, lectures, films, and exhibitions–6sqft has teamed up with the Center for Architecture to explore some of their 70+ partner organizations.

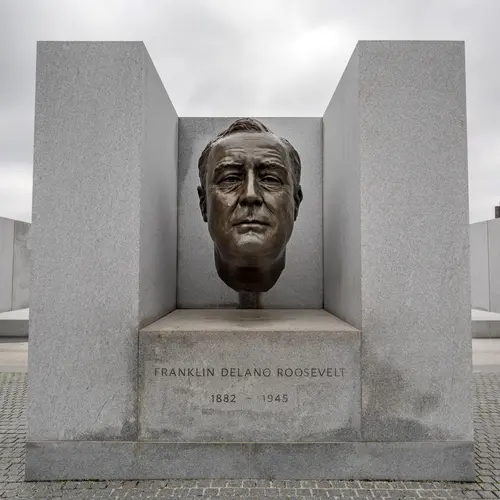

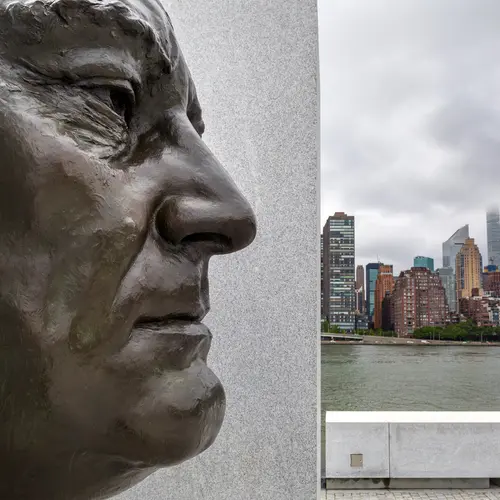

In 2012, 40 years after it was conceived by late architect Louis Kahn, Four Freedoms Park opened on four acres on the southern tip of Roosevelt Island. Part park, part memorial to FDR (the first dedicated to the former president in his home state), the site was designed to celebrate the Four Freedoms that Roosevelt outlined in his 1941 State of the Union address–Freedom of speech, of worship, from want, and from fear. In addition to its unique social and cultural position, the Park is set apart architecturally–the memorial is constructed from 7,700 tons of raw granite, for example–and horticulturally–120 Little Leaf Linden trees are all perfectly aligned to form a unified sight line.

And with these distinctions comes a special team working to upkeep the grounds and memorial, educate the public, and keep the legacy of both Kahn and Roosevelt at the forefront. To learn a bit more about what it’s like to work for the Four Freedoms Park Conservancy, we recently toured the park with Park Director Angela Stangenberg and Director of Strategic Partnerships & Communications Madeline Grimes, who filled us in on their day-to-day tasks, some of their challenges, and several secrets of the beautiful site.

From the top, the lawn looks (and is) triangular, but it takes on a different shape as you approach the memorial.

Tell us a bit about your background and what brought you to Four Freedoms Park?

Angela: I grew up on the south shore of Long Island and was exposed to wonderful State and National Parks, places like Sunken Forest on Fire Island and Bayard Cutting Arboretum in Great River. My undergraduate degree is in Environmental Studies and Anthropology; I’ve studied Sustainable Landscape Management at New York Botanical Garden; and I’m currently working on a Masters of Public Administration at Baruch.

I cut my teeth working as an Urban Park Ranger at Fort Totten Park in Queens about 10 years ago, leading tours and environmental education programs and canoeing programs in Little Neck Bay. Fort Totten is a never-completed Civil War-era fortification, one of those places that makes you feel like you’re discovering something secret. I went on to work at other parks and public gardens, which eventually led to my current position at Four Freedoms Park Conservancy in 2014.

Madeline: I’ve had a bit of a circuitous background. I studied sociology and history in university and worked in pension governance consulting, technical writing, and advocacy before joining the team at Four Freedoms Park Conservancy in 2014. I was attracted to working with the Conservancy for a number of reasons, but two really stick out — one, the Park itself is exquisite, it has this power to make you feel at once both very connected to the city and very removed from it, and two, I really love the mission of connecting people to the four freedoms in inspiring ways. I have a role that allows me a lot of creative autonomy and expression, which is incredibly rewarding in and of itself.

Originally, Roosevelt Island ended at the Smallpox Hospital (today a ruin, pictured in top photo). But in the late 1950s and ’60s, the island was extended to its current southern point using landfill from on-island excavation. The five Copper Beach trees were 30 years old when planted.

What does a typical day look like for you?

Angela: Before opening the gates to the public, I prepare an opening report of who is working, weather conditions, and tours/programming. Our maintenance crew scrubs the granite clean from the wildlife who visits overnight – usually gulls leaving scraps of East River crabs and fish, but most labor intensive is cleaning up after the resident goose community who graze overnight and leave a prolific mess. On any given day we have all sorts of visitors who we welcome: architects on pilgrimage, photographers, students, locals, and tourists.

We are very affected by seasons as an outdoor place. In February, we are making sure areas that are unsafe are barricaded from the public and paths are cleared from snow and ice – we do not use salt or de-icer on the monument. Conversely, in the summer we are preparing for high volume days with more staff and attention to landscaping maintenance. And we offer visitors tours with a guide who help interpret the memorial, Four Freedoms, and Louis Kahn’s design.

Madeline: I’m responsible for developing our roster of public programs and events and overseeing our educational initiatives at the Park, as well as serving as the Conservancy’s community liaison. As Angela mentioned, the space is very seasonal, so my day-to-day varies quite a bit depending on the month. Our public programming typically takes place between April and October, so in those months, I spend my time finalizing event details, overseeing and promoting events, and ensuring everything goes off without a hitch. In the winter months, it’s much more about planning, developing new partnerships, and figuring out the stories we want to tell and the ways we want to deliver our mission through public and education programs.

The granite was specified by Kahn to be quarried from Mount Airy, North Carolina. The stones were so heavy that they couldn’t cross the bridge and therefore had to be trucked to New Jersey and sent to the construction site via barge. It then took five types of cranes and 100 stone setters to get them in place–the heaviest stone-setting job ever in NYC.

The granite was specified by Kahn to be quarried from Mount Airy, North Carolina. The stones were so heavy that they couldn’t cross the bridge and therefore had to be trucked to New Jersey and sent to the construction site via barge. It then took five types of cranes and 100 stone setters to get them in place–the heaviest stone-setting job ever in NYC.

What’s your biggest day-to-day challenge?

Angela: Our biggest challenge is protecting 7,700 tons of untreated white granite from damage. It’s a raw and porous stone that absorbs stains easily, making it a delicate element to maintain. We are extra vigilant during high visitation days and venue rentals. Our approach to stain removal is gentle, using dish soap and water. I love it when it rains because it gives the granite a bath and waters the trees–a win-win.

Is it challenging working on Roosevelt Island in terms of transportation?

Angela: Getting here is part of the fun! The aerial tram is a must for first-time visitors. There is also a new ferry terminal on the island, the F train, and ample six-hour street parking if you plan to drive. For cyclists, we have bike parking on site.

The 120 Little Leaf Linden trees are part of NYC’s Million Trees campaign. They blossom in June, and in the winter their bark turns a cinnamon hue.

In terms of the landscaping, how does Four Freedoms Park differ from most NYC parks?

Angela: The second challenge to this is keeping the trees alive and happy. Here is a completely artificial site and harsh growing environment. Exposed to salt air and water, the reflection of the sun, and winds of the East River, living things have the cards stacked against them. Despite it all, we’ve been successful at keeping the living collection alive. We do things like wrap the most exposed trees in the winter and take moisture readings to determine irrigation rates. We also maintain an organic landscape program.

What have been the biggest changes since the park opened in 2012?

Madeline: The Park opened to the public nearly 40 years after it was designed, in large part due to the perseverance of a small group of very dedicated individuals. Certainly, after the Park was built, there was a shift from building something, to operating and programming the space, and more recently to really attuning our mission to inspiring people about universal human rights.

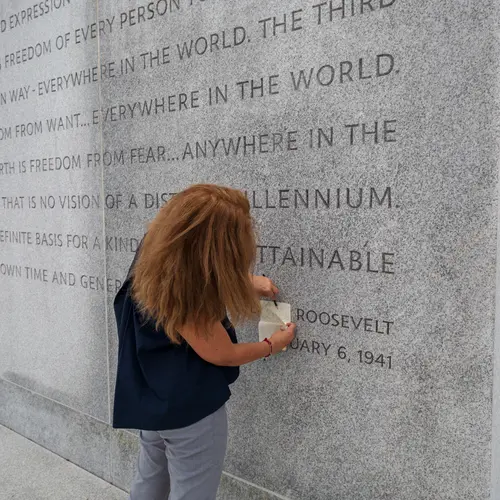

The Four Freedoms inscription was hand-carved on site by the John Stevens Shop, founded in 1705. The font was specially created by the carver, Nick Benson. Because of the nature of the speech, the proximity to the United Nations was intentional.

If there was one thing you could tell visitors about the park, what would it be?

Angela: I think it’s important to meditate on the Four Freedoms, our namesake, which were FDR’s ideas about universal human rights being the basis of a secure future for humanity–a heavy and relevant subject matter for our times. The memorial is an experiential place that packs in a lot of the ineffable. I also enjoy the nods to ancient architecture and that the granite is monolithic in scale at the Room yet found in the most minuscule granite sands mixed into the cobblestone grout.

Madeline: One of the things I find incredibly compelling about this space is the story of how it was built. As I mentioned, it took nearly 40 years to make this memorial a reality, long after its architect had passed away. The fact that this space exists at all is really a testament to the power of a dream.

The handrails are identical to those designed by Kahn for the Kimbell Art Museum in Forth Worth, Texas.

The handrails are identical to those designed by Kahn for the Kimbell Art Museum in Forth Worth, Texas.

What’s your favorite “secret” of the park?

Angela: That the monument can sing the song of quetzal. If you stand in front of the grand staircase and clap, the echo produced sounds a bit like the quack of a duck. One of our visitor experience guides discovered this as she was researching the similarities of Mayan pyramids to Kahn’s design. The echo is explained by Bragg’s Law but takes on mystical meaning in Mayan mythology as the song of quetzal, a bird who brings messages from god.

And don’t forget to peek between the one-inch gaps in the columns in the room. You will see the light splay and if you reach between to touch, will find the only place in the Park where the granite is polished to aid this visual effect.

Madeline: In the “Room” strung between the two granite columns is a very thin piece of fishing line that is used to ward off seagulls from setting up camp in the open-air granite plaza. When the line moves with the breeze, it seems to appear and disappear, frightening the birds. There’s something so simple about this solution that I just love.

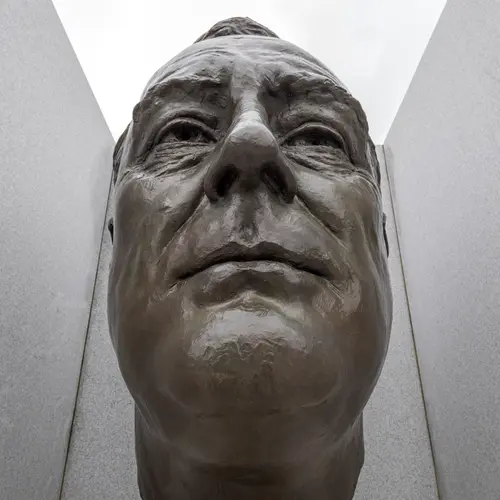

The “room” is made up of 190 individual stones. Each 36-ton column is set one-inch apart and polished on the interior-facing surfaces to create an optical illusion with light. Each hour it’s different!

Favorite time to experience the park?

Angela: I like the Park anytime it’s quiet, but especially in the morning – you can sense the city waking up. My favorite time of year is mid-June because the lindens are in bloom. Not only do the blossoms smell lovely, but they are also said to have a natural sleep-inducing effect. Bees come out en masse to join the party in a cacophony of pollinators.

Madeline: I love twilight at the Park. There’s this moment just after the sun has fallen and the stars make their entrance that is pure magic. If you stay long enough, you can watch all of Manhattan flicker to life – the UN building, the American Copper Towers, the apartment buildings along the East River. It’s remarkable how both far away and close you can feel to the city in those moments.

And for time of year… summer. But I can’t stand the cold, so summer is always going to be my response.

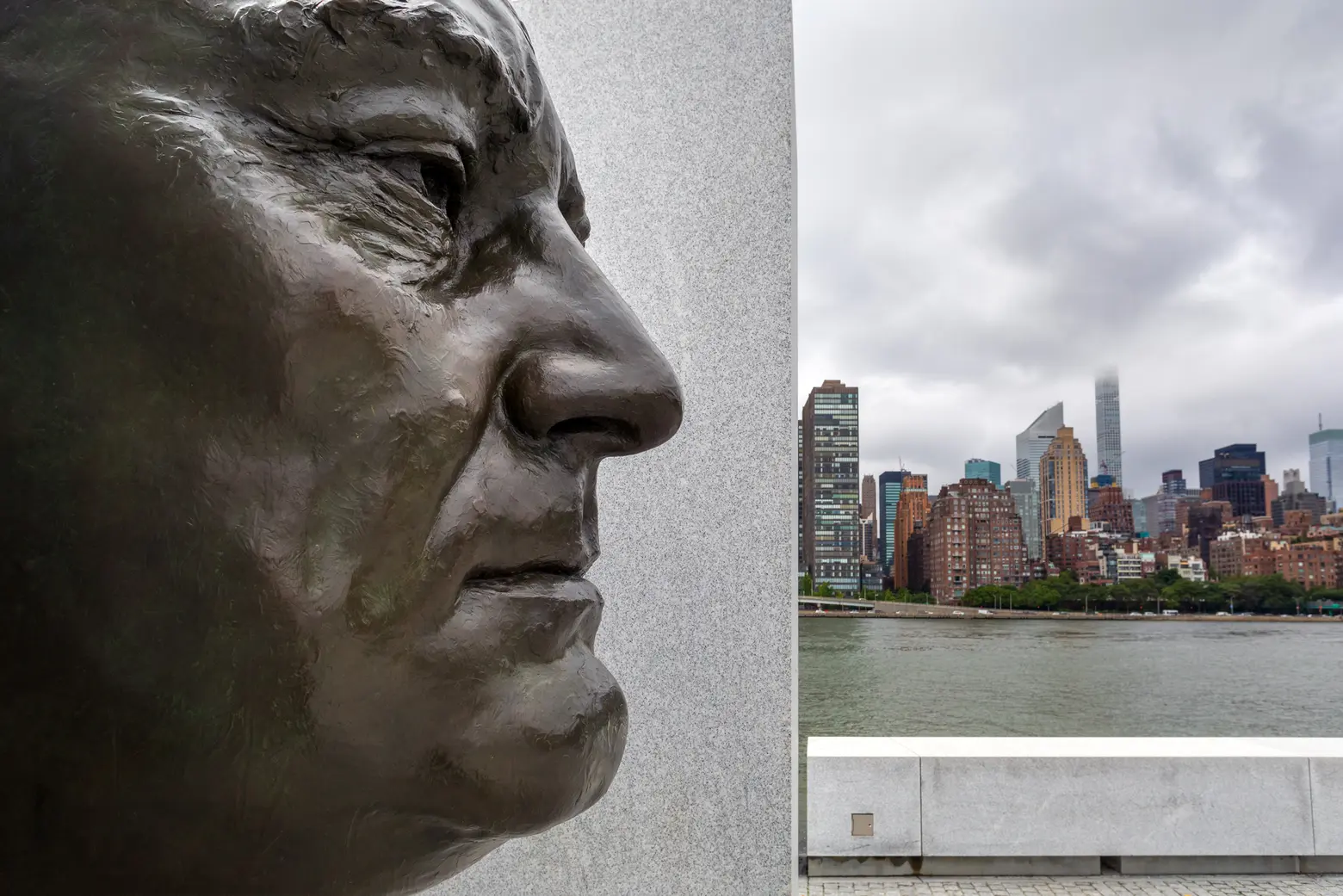

The bust of FDR is by famed sculptor Jo Davidson. He sculpted it from clay in 1933; this is an enlarged bronze casting that measures six feet tall and weighs 1,050 pounds.

What has been most interesting for you to learn about FDR?

Angela: A few years back, Posters for the People hosted a screen printing workshop at the Park about WPA Posters and the many jobs for artists that were created as part of the New Deal. I loved learning about the artwork and that there are many WPA murals and artwork around NYC to this day.

Madeline: FDR’s contributions to the formation of the United Nations. In fact, his Four Freedoms speech lay the basis for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted in December 1948.

The promenades are sloped, creating another dimensional illusion.

What about Louis Kahn?

Angela: Louis Kahn framing architecture in almost spiritual terms, his appreciation for nature and light. The longer I work here, the more I glean affection for his work.

Madeline: I second Angela on the way Kahn speaks about architecture and design. Learning about Kahn’s design ethos generally — and the ways he used architecture to meet the humanistic needs of communities — has been really fascinating.

The rip-rap rock barrier protects the memorial from erosion. It’s made from 11,000 cubic yards of hand-placed granite gneiss, more than half of which was recycled from the site.

Any exciting upcoming plans for the park you can fill us in on?

Angela: In the coming weeks we are wrapping up a large-scale renovation of cobblestone surfaces. We’ve completed the majority of 30,000 square feet of surface area and will resume in the Spring when we press reset on all weather-dependent projects. We are constantly evolving our approaches and methods of maintaining a masterpiece.

Madeline: We’re working on a really exciting slate of public programs that leverage the current tide of activism and interest in four freedoms with our unique space.

RELATED:

- Was Louis Kahn’s Four Freedoms Park Inspired by the Masonic Pyramid on the $1 Bill?

- Where modernism meets tradition: Inside the Japan Society’s historic headquarters

- Take a tour of Dead Horse Bay, Brooklyn’s hidden trove of trash and treasures

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft unless otherwise noted. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.