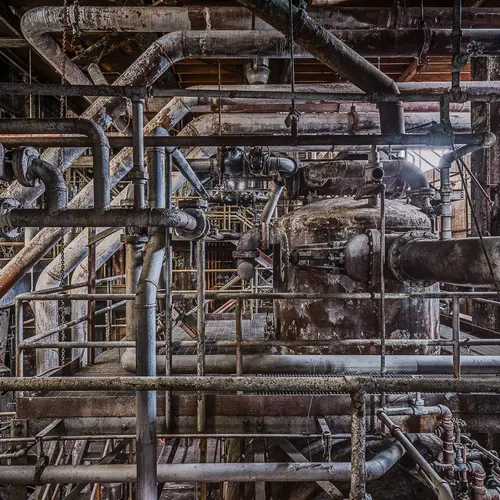

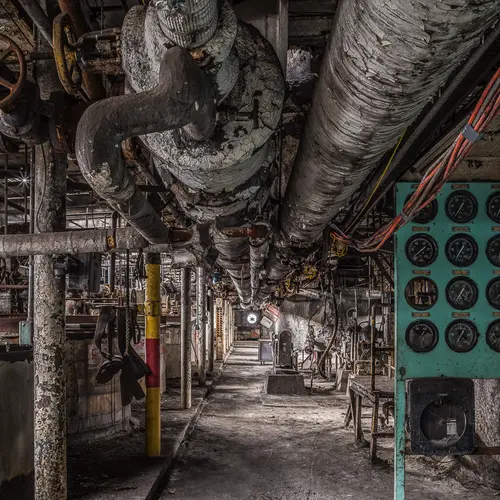

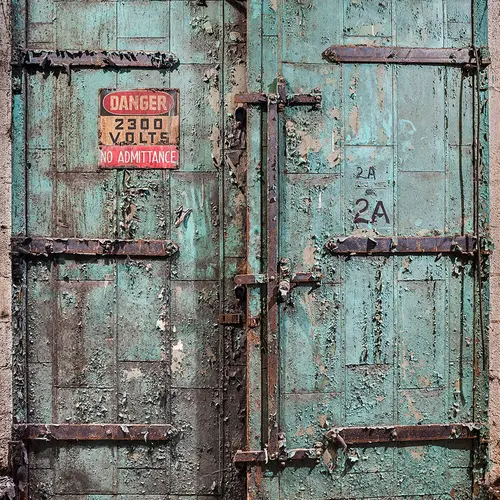

The Urban Lens: See the last photographs of the abandoned Domino Sugar Factory

All photos © Paul Raphaelson

6sqft’s series The Urban Lens invites photographers to share work exploring a theme or a place within New York City. In this installment, Paul Raphaelson takes us through the Domino Sugar Factory before its redevelopment got underway. Are you a photographer who’d like to see your work featured on The Urban Lens? Get in touch with us at [email protected].

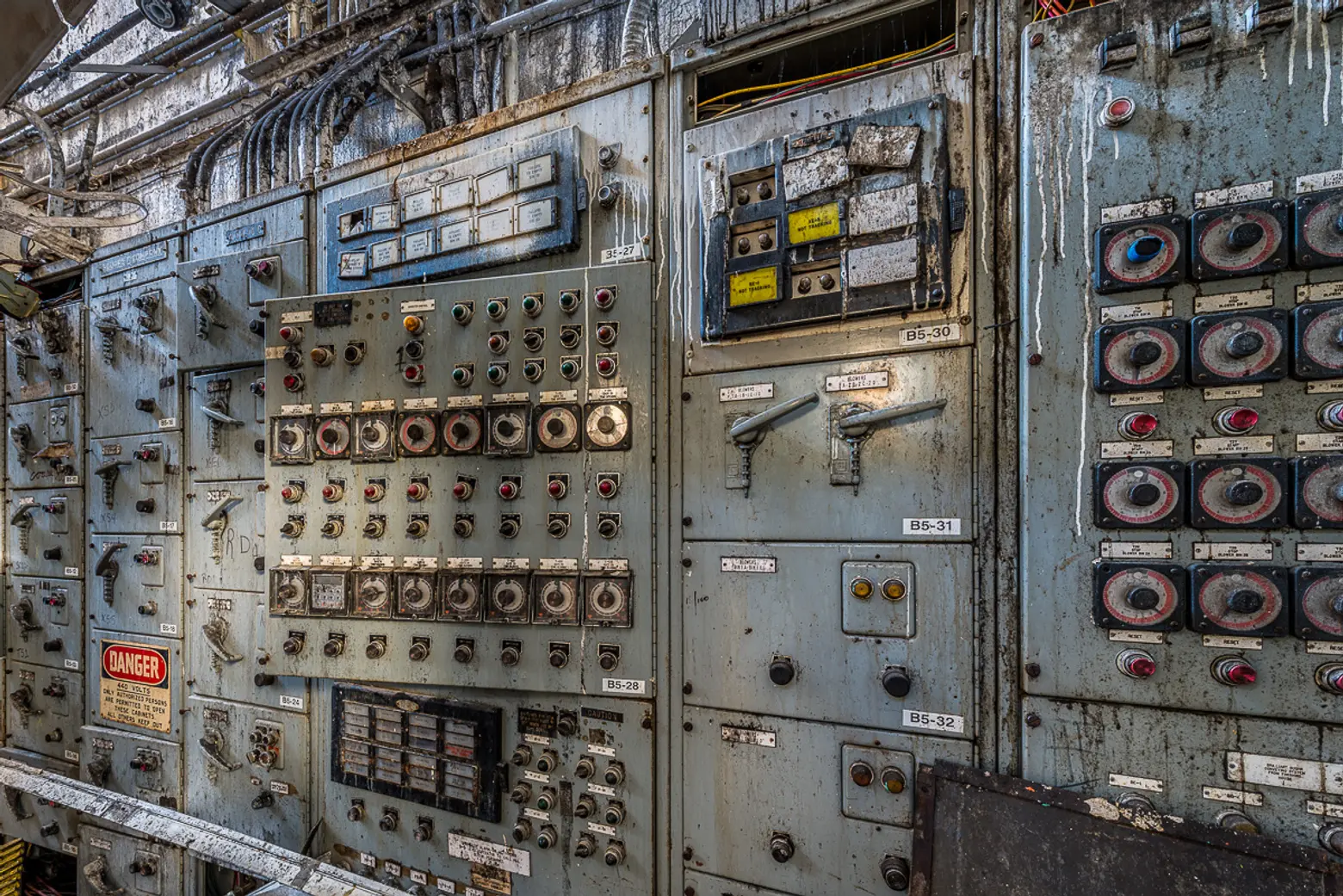

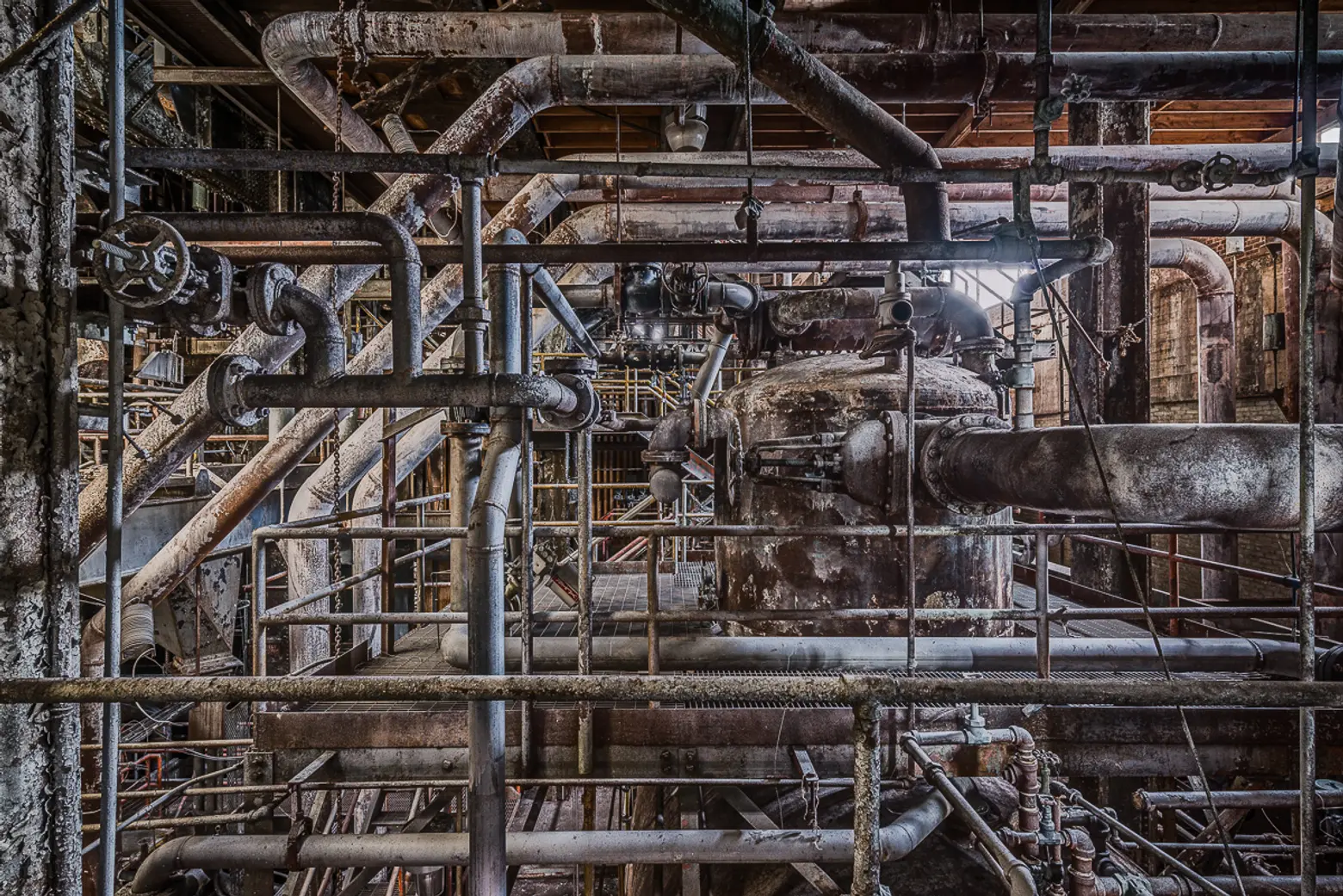

The term “ruin porn” was born out of generations of street photographers venturing into neglected, decaying, and off-limits spaces, but today it’s become more of a mainstream trend to fluff one’s Instagram feed. So when Brooklyn-based artist Paul Raphaelson received the chance in 2013 to be the last photographer allowed into the then-abandoned Domino Sugar Factory, he knew he didn’t want his project to simply “estheticize surfaces while ignoring the underlying history.”

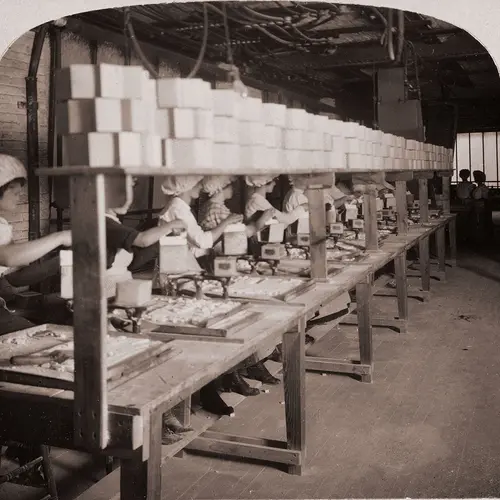

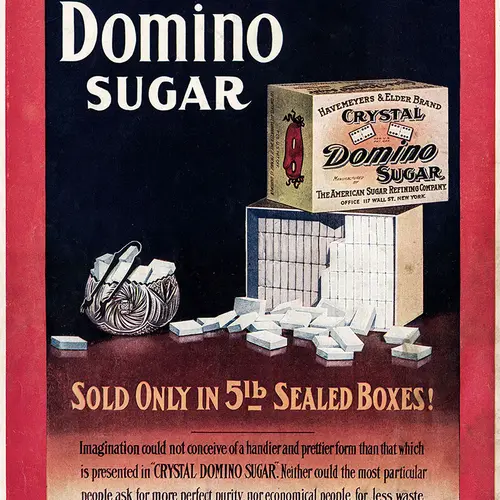

His stunning photos of the 135-year-old structure still “capture the sublime sense of spectacle,” but they also accompany archival maps, newspaper clippings, corporate documents, and even interviews with former Domino Sugar Factory employees, all of which come together in his new book “Brooklyn’s Sweet Ruin: Relics and Stories of the Domino Sugar Refinery.” Raphaelson shared his stunning images with us and also shared his thoughts on “urban exploration,” his process in compiling a comprehensive history of Domino, and his thoughts on the recently approved plans for the site.

How did you get into photographing abandoned spaces?

I’ve photographed desolate places, but this is my only real abandoned space project. It came about because for me, living in New York has been closely connected to old factory buildings. When I moved here in 1995, I joined friends living on the Brooklyn waterfront in repurposed victorian millhouses. I loved the architecture, the rawness, the sense of history, the sense of possibility … that you could do anything you dreamed of in these big old spaces.

Several years ago I started photographing spaces like the ones I’d turned into studios. But they weren’t abandoned spaces in the way you’re probably thinking. And they weren’t dramatic—they felt more like painted-over canvasses, waiting for their next incarnation.

Had you always been interested in Domino? How did you gain access?

When I was in the middle of my empty industrial space project, I read that Domino was going to be demolished. Domino had been in my peripheral vision, but I hadn’t thought about photographing it. It then seemed like maybe it would fit my project—and that it would definitely be gone soon. So I started writing emails, asking for access.

I considered sneaking in, but those days seemed over—the refinery was humming 24/7 with asbestos abatement crews and demolition engineers. And it’s hard to do a serious project when you’re looking over your shoulder the whole time.

After around six months of emailing back and forth, the developers agreed to let me in. I was in for some surprises. The insides of the refinery were nothing like the empty industrial spaces I’d been photographing. It was a whole different experience and quickly became its own project.

At first, the developers gave me one day’s access. They said they’d been flooded with requests and narrowed it down to five photographers. They gave us each a day in August 2013. That day I worked harder than I’d ever worked, but I barely scratched the surface.

I knew the developers wouldn’t want to give me more time—they had little incentive to take on the liability or to delay their development plans. So I had the idea of proposing a book. I used the pictures from that first day, did research, and put a team together with a well-known photography editor and an architectural historian. The developers said yes to my proposal. Which was amazing—I’d have a full week in October to photograph. But it also meant I had to do the book. So that little gambit ended up rewriting the next four years of my life.

Would you consider yourself an “urban explorer?”

I have friends who do this, including ones who wrote a book on the topic (Invisible Frontier). I admire their adventures but think they’re doing something rather different from what I do.

Urban exploration photography seems to be about documenting the adventure itself, as much as it’s about anything else. I think it has a connection to street art and also to the survey photography of the American West (the expeditions used the photographs to publicize themselves and to raise funds). Like street art, urbex photos often have an element of performance, and of showing that “I was here.”

My work isn’t about that, although sometimes we share subject matter, and I’ve done my share of trespassing and wandering into precarious places. My work is more about the thing photographed. It’s also about broader ideas beyond the photograph, and about problems in formal picture-making.

Your book is more than just photos; you worked with architectural historian Matt Postal to provide a comprehensive, historic overview of the factory, including archival maps, newspaper clippings, and corporate documents. Why was it important to you to include these materials, rather than just presenting a “ruin porn” photo series?

Well, the phrase “rather than just presenting a ‘ruin porn’ photo series” hints at the answer. As I researched the project, I discovered just how much contemporary ruin photography there was. It’s practically ubiquitous. I’m not used to working in a genre that’s trendy, and this one might be trendy to the point of being overdone.

Beyond that, it’s come under sharp criticism from many groups. People in Detroit, especially, call it out for being a kind of hipster imperialism. They see wealthy, mostly white, tourists with expensive cameras stomp across their lawns and gleefully photograph fossils of their former homes and livelihoods. Photographers often do this without a hint of serious interest in what they’re looking at. They estheticize surfaces while ignoring the underlying history and suffering.

So here I was, taking on this huge new project, discovering that I was walking into a thicket of clichés and exploitation. How to make it more than just a ruin porn photo series became the central problem I had to solve.

I was able to address some of this problem through the photography and the photo editing, but much of my solution came with the supporting materials and the overall structure of the book. I still wanted the photographs to be beautiful and evocative—to capture the sublime sense of spectacle I experienced while inside Domino. But I wanted to place the pictures in the context of history and personal stories, so viewers could get a sense of the richness and weight of what they were seeing.

There’s also an essay where I look my own connections to these old spaces. And I address some of the more philosophical and art-historical questions about our attraction to contemporary ruins. I think this attraction is symptomatic of some interesting and troubling elements our culture. So it was necessary, in my view, to make the book this expansive and complex. It’s a testament to Christopher Truch’s art direction that it holds together at all.

You also included interviews with former factory employees. How did you track them down?

Facebook! At first, I looked for names in newspaper articles about the strike in 1999/2000 but didn’t get anywhere. Then I discovered the workers had a thriving Facebook community. So finding them got easy. But finding ones who wanted to talk was hard. Most just had no interest. I was surprised because journalists had almost all taken their side and treated them fairly during the labor disputes. But for whatever reason, I only found a handful who wanted to be in the project. That said, I was lucky—the ones who talked with me were awesome. They could have talked for days. And they remembered everything.

I also talked to a bunch of current workers at the Domino Yonkers refinery, who had previously worked at the Brooklyn refinery. I learned tons from these guys about the technical side. But since they still worked for for the company, and had been in management back in Brooklyn, they were not as forthcoming with interesting stories as the other guys.

What was the most surprising thing you learned from the interviews?

That for most of their careers, the workers loved their jobs. More than I’ve ever loved a job. The place was their life and their community. The history shows that for most of Domino’s existence, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was an industrial hell hole. But the workers I talked to came from a golden era when union contracts were strong and management was benevolent, up until the last few years, when new owners brought back Industrial Revolution attitudes toward management.

I learned some other things that are so surprising I can’t repeat them. About connections between the Domino’s parent union (the Longshoremen) and several of the NYC crime families. One reason the union was able to negotiate such great contracts is that everyone was terrified of it. This gave the workers leverage, but also led to some Tarrantino-esque drama for workers who unwittingly wandered into the middle of union business.

How do you feel about the recently approved plans for the site?

In my personal utopia, the site would be left alone, like a Roman ruin, for people like me to run around in and make art of all different kinds. But this is just a selfish delusion. My number-two fantasy would be some kind of public space that preserves much of the site, with buildings converted to museums, galleries, libraries, and other kinds of public spaces, parks, and possibly also live/work studios and commercial space for non-profits and carefully curated businesses. But with the value of the waterfront, this wasn’t going to happen either.

Considering that high-end architecture was inevitable, I think that the current plans (designed by SHoP architects) are pretty nice–way better than the horror shows you see elsewhere on the Williamsburg and Greenpoint waterfront. And better than the plans proposed by the previous developer (CPC). I especially like the new plan for the glass-domed interior of the main refinery building. I’d probably like the towers more if they weren’t so tall and were more in scale with the refinery and the bridge.

Any other projects you’re working on that you can tell us about?

Any other projects you’re working on that you can tell us about?

I have a couple of ongoing experiments, and one completed project that I’d like to get out into the world. The completed one came right before Domino—it’s a series of photographs made on the subway, using windows and reflections. They’re unlike any subway photographs I’ve seen. I think it’s the most interesting project I’ve done, and also the one that’s most relevant to what’s going on in contemporary art. I’d like to do a book of this work.

The experiments are in early stages, so I’m not ready to talk about them yet. They’re quite different from anything else I’ve done.

+++

RELATED:

- Roasteries and refineries: The history of sugar and coffee in NYC

- Artist Kara Walker’s Provocative New Exhibit Will Allow You to Tour the Domino Sugar Factory

- All Domino Sugar Factory coverage

All photos © Paul Raphaelson

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

I love to see what my old neighborhoods looked like. I guess I lived in Brooklyn all my life.My son works on time in the studio around there. I’m proud of Brooklyn. thank you.