Past Prisons: Inside the new lives of 7 former NYC jails

A 1938 photo showing the Women’s House of Detention south of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, via NYPL

The past week has been full of news about Rikers Island and Mayor de Blasio’s announcement that the notorious prison will be closed and replaced with smaller facilities throughout the boroughs. Ideas for re-use of its 413 acres have included commercial, residential and mixed-use properties; academic centers; sports and recreation facilities; a convention center; or an expansion of nearby LaGuardia airport. And while anything final is estimated to be a decade away, this isn’t the first prison in NYC to be adaptively reused. From a health spa to a production studio to a housing development, 6sqft explores the new lives of seven past prisons.

Rikers Island via Wikimedia

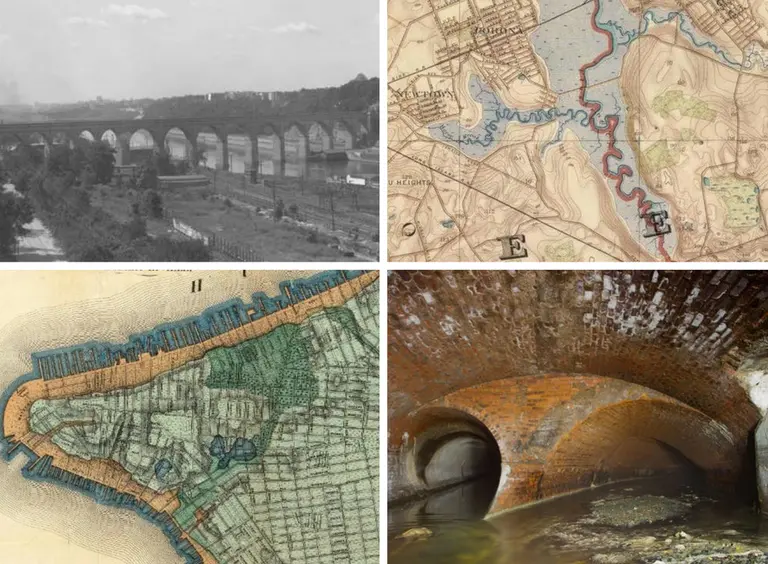

A bit of background

In 2011, Governor Cuomo issued a directive to close seven prisons in the state, two of them in New York City. The move was taken because of prison underpopulation, not because of widespread abuse such as that prevalent at Rikers, and was estimated to save the state $184-million over two years.

In 1999 in New York State, for example, the prison population was 71,600 according to the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision. Today it is 51,500, a decline of 28%. In New York City, the average daily population is 9,362, compared with 11,478 at the end of 2013, an 18% drop. The trend seems likely to continue. In 2016, according to the mayor’s office, 2016 was the safest year in recent history—burglaries were down 15%, shootings down 12%, and homicides declined five per cent.

Image via NYPL

Image via NYPL

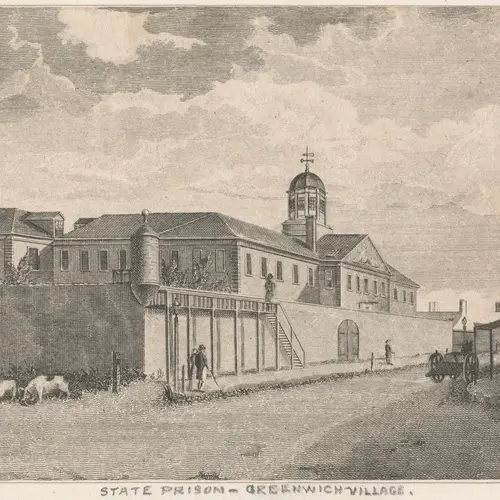

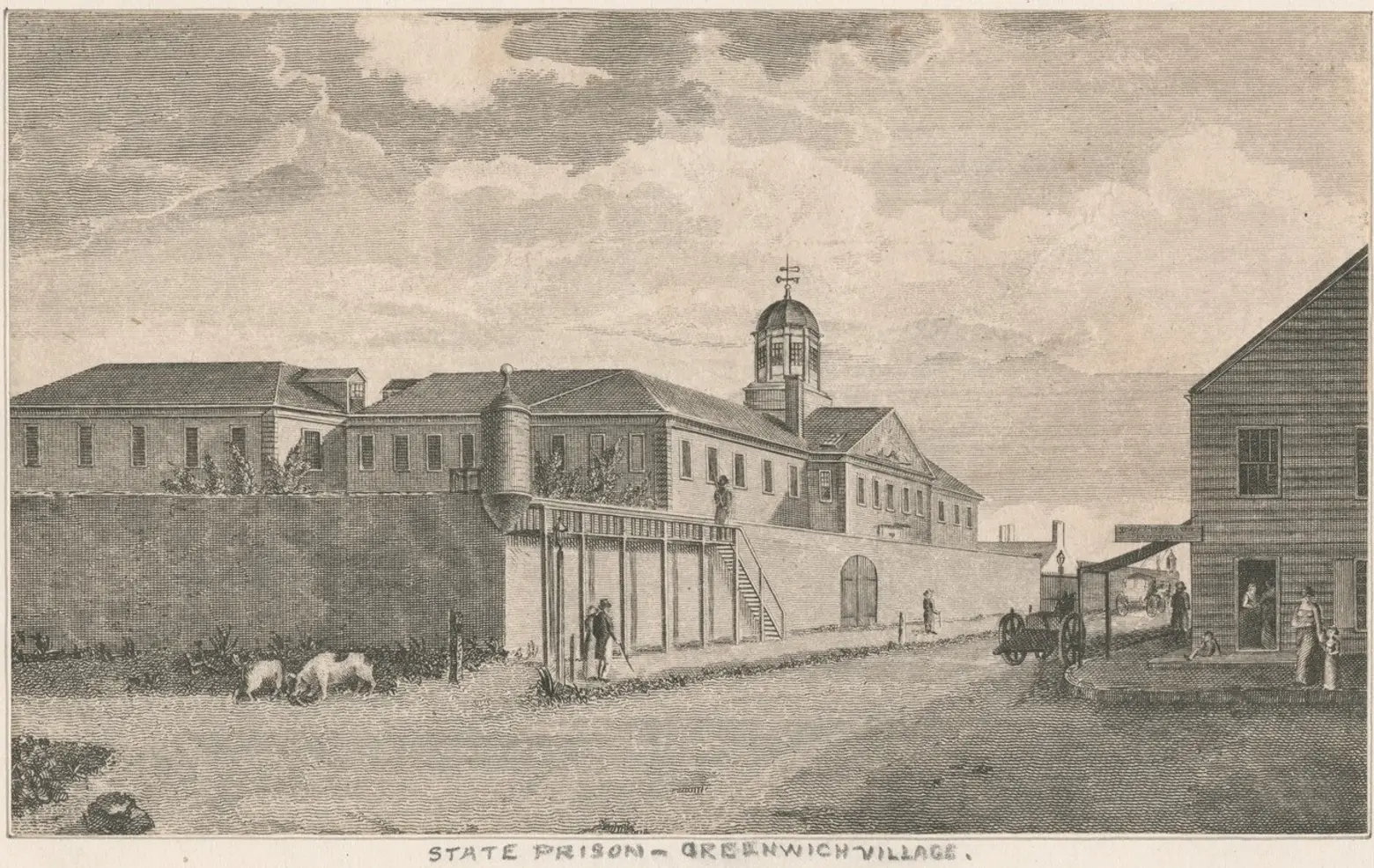

1. Newgate

Adaptive reuse of prisons is not a new thing. In 1796-97, a huge prison was erected on a promontory into the Hudson occupied today by the land between Christopher and Perry Streets west of Washington Street. Called the State Prison at Greenwich and nicknamed Newgate after the infamous 18th century London prison of that name, it was designed by Joseph Mangin, one of the architects of City Hall. Despite walls 22 feet high on the water side and 14 feet high elsewhere; despite the prison practice of teaching trades; despite such amenities as a garden, bathing rooms and a place to worship, Newgate was the site of three major uprisings, including one in May 1804 in which prisoners set fire to and almost destroyed part of the prison. Possibly because of all this violence, the prison became a tourist attraction which, it has been said, spurred residential development of this part of Manhattan. It is also said that the expression, “being sent up the river,” originated with Newgate, for it was upriver of the main settlement of Manhattan.

However, in 1826 the city bought Newgate from the state and began to transfer its inmates to a new prison at Ossining known as Sing Sing. The city then, in 1829, sold the prison to Jacob Lorillard, who repurposed the buildings into a health spa, opening in 1831. It lasted only a few years, however, and was ultimately demolished.

Conceptual renderings of the Peninsula, via WXY Architects + Urban Design

Conceptual renderings of the Peninsula, via WXY Architects + Urban Design

2. Spofford Juvenile Detention Center

The New York State Office of Children and Family Services announced in June 2011 the closure of four youth detention facilities, one of which was the Spofford Juvenile Detention Center in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx. Built in 1957, the facility was decried for years for its vermin-ridden, dark, dank conditions. The city’s Economic Development Corporation and Department of Housing Preservation and Development are the agencies working to develop the area, now known as the Peninsula. The prison is expected to be torn down and its five-acre site replaced with a $300 million mixed-use complex offering 740 units of affordable housing, commercial and manufacturing space, health care, and recreational activities. A staff person at WXY Architects + Urban Design, the design firm involved, said that work is at the drawing-board stage now.

Aerial view of Arthur Kill Correctional Facility, via Empire State Development

Aerial view of Arthur Kill Correctional Facility, via Empire State Development

3. Arthur Kill Correctional Facility, Staten Island

Arthur Kill was closed in response to the governor’s directive in December 2011. There was talk about housing refugees from Hurricane Sandy there in 2012—the building could hold 900 souls—but none of the island’s residents liked the idea. It has, however, been successfully used as a film and production studio, marketed principally by Broadway Stages, which owns and operates filming sites.

Broadway Stages tried to buy Arthur Kill in 2012 and nearly succeeded, but its offer was denied by State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli because of investigations of the company’s fundraising donations to Mayor de Blasio. Bells went off when administrators realized that Broadway Stages had arranged with Empire State Development to buy the facility for $7 million when it had reportedly been appraised for as much as $52 million. Although its status is still in limbo, Broadway Stages continues to manage the site and pays for security and maintenance there.

Current view of the site

Current view of the site

4. Fulton Correctional Facility

Some prisons have not only an after-life but a before-life. The Fulton Correctional Facility at 1511 Fulton Avenue in the Bronx, for instance, is the other New York City facility that Cuomo ordered closed. In 2011 and for almost 40 years before that, it was a minimum-security prison capable of housing up to 900 people, but it had a life before that.

Fulton was built in 1906 as an Episcopal church and 18 years later became a Young Men’s Hebrew Association and synagogue. In the 1950s it became a nursing home, then a drug rehabilitation center. Its stint as a minimum-security prison began in 1975. In 2015, the building was taken over by deed transfer to the Osborne Association, an 82-year-old prison reform group headed by Elizabeth Gaynes. The organization is now putting together financing for construction expected to start this summer on a temporary housing and job training center for people with roots in the neighborhood who have recently been released from prison.

A complete gut-renovation is planned, expecting to cost about $9 million, with $6 million of that coming from the Empire State Development Fund, $650,000 from the Bronx Borough President’s budget, and the remainder raised privately. An apiary on the roof will engage residents in cultivating honeybees, two floors are residential, and other areas of the building will be devoted to training people in catering and the light manufacture of items such as furniture.

A previous speculative rendering of a redeveloped Bayview Correctional Facility from the New York Governor’s Office. Deborah Berke Partners has not released images of their proposal.

A previous speculative rendering of a redeveloped Bayview Correctional Facility from the New York Governor’s Office. Deborah Berke Partners has not released images of their proposal.

5. Bayview Correctional, Women’s Prison

Not part of the governor’s directive, an additional prison, Bayview Correctional Facility, at 550 West 20th Street in Manhattan, also had an earlier life. Built in 1931 as the Seaman’s House, YMCA housing for merchant mariners, Bayview next became a drug-treatment center owned and operated by the state, then a prison in 1974 and finally a women-only facility in 1978. It was designed in the art deco style by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, architects of the Empire State Building. During Hurricane Sandy, it was inundated by 14 feet of water and forced to close. All its 170 women inmates were moved elsewhere.

It will be adapted and redesigned by Deborah Berke Partners, who won a competition to remake the 100,000-square-foot building, as a women’s center. The conversion is being led by NoVo Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to ending violence against women and girls, and the Goren Group, a development firm led by women.

Current plans are to demolish the six-story annex added to the original eight-story building in 1950, add offices for both non-profit and commercial enterprises, terrace gardens, and an art gallery. Some of the existing facilities will be restored and repaired: for example, a mosaic-lined swimming pool that has been drained will be fixed and refilled. A small chapel with stained-glass windows will be refurbished. Office space will pay for the building’s $3.5 annual million rent to the Empire State Development Corp.

Jefferson Market Garden today

Jefferson Market Garden today

6. Women’s House of Detention

Another women’s prison in Manhattan did not fare so well. Known as the Women’s House of Detention, it was built around 1930 beside the Jefferson Market Courthouse, fronting on Greenwich Avenue, Sixth Avenue and West 10th Street. Built to house 457, at its worst it held 750, requiring inmates to double up in small cells. For years it was the site of street theater as friends and relatives of inmates gathered gather outside on the sidewalk Saturday afternoons to conduct shouted conversations with women incarcerated inside, something most Greenwich Villagers hated.

In 1962, women’s facilities began to be built on Riker’s Island, and women prisoners were transferred there gradually until finally the building was emptied and closed in 1972. Some local people wanted the building saved for use as a retirement home, a school or another community use, but Mayor John Lindsay was adamant about demolishing it, and by 1974 it was gone, replaced by the Jefferson Market Garden, a privately supported, volunteer-run garden.

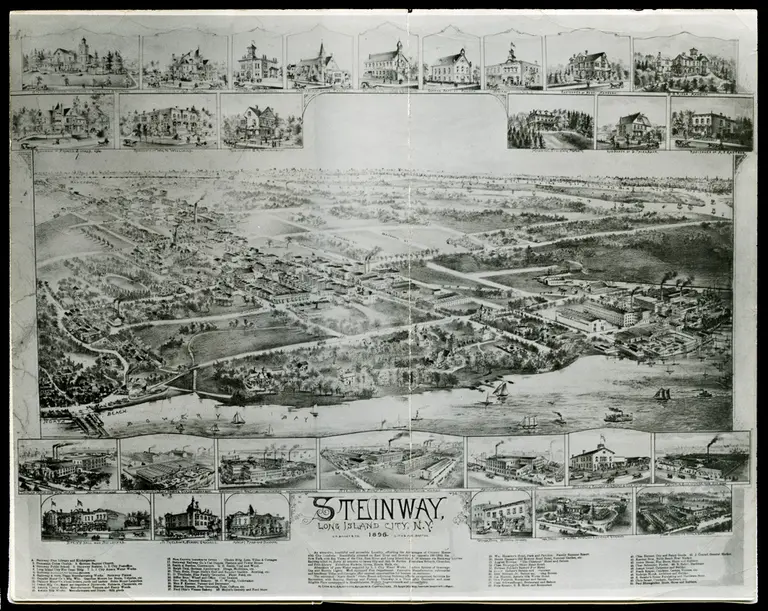

7. Vernon C. Bain, aka The Barge

While redesigning prisons for new uses is challenging, providing space for a potentially fluctuating prison population is, too. That realization gave rise to the 1992 creation of the Vernon C. Bain Correctional Center, a floating barge and the third of its kind in New York City. Bain, named for a popular warden who died in an automobile accident, is designed to hold up to 800 individuals from medium- to maximum-security prisons on a temporary basis, and to do so without encountering neighborhood resistance, since the barge is in the Hudson River. It was closed in 1995 because of reduced crowding in city jails and reopened in 1998 for two years in response to an increased need for juvenile detention space. Today it is primarily a processing center.

+++

RELATED: