Nomad’s Tin Pan Alley, birthplace of American pop music, gains five landmarks

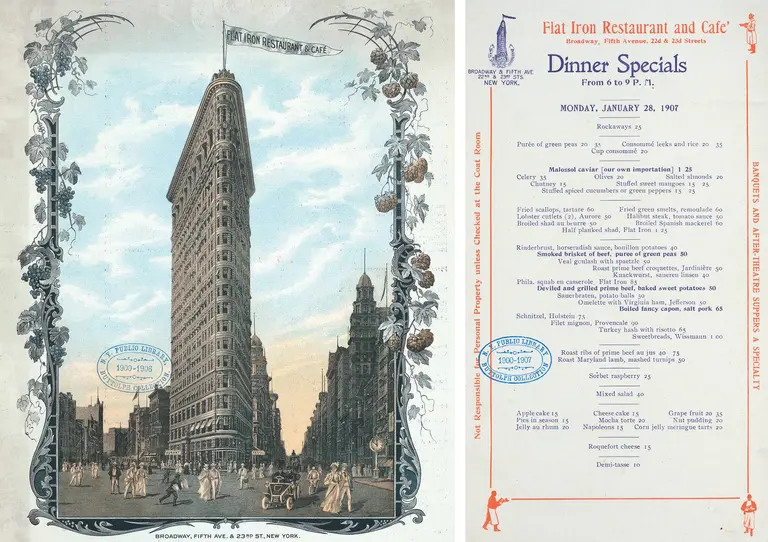

Tin Pan Alley buildings; Photo by Eden, Janine and Jim on Flickr

The Landmarks Preservation Commission on Tuesday designated five Nomad buildings linked to the birthplace of American pop music. Tin Pan Alley, a stretch of West 28th Street named to describe the sound of piano music heard from street level, served as an epicenter for musicians, composers, and sheet music publishers between 1893 and 1910. During this nearly two-decade period, some of the most memorable songs of the last century were produced, including “God Bless America” and “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”

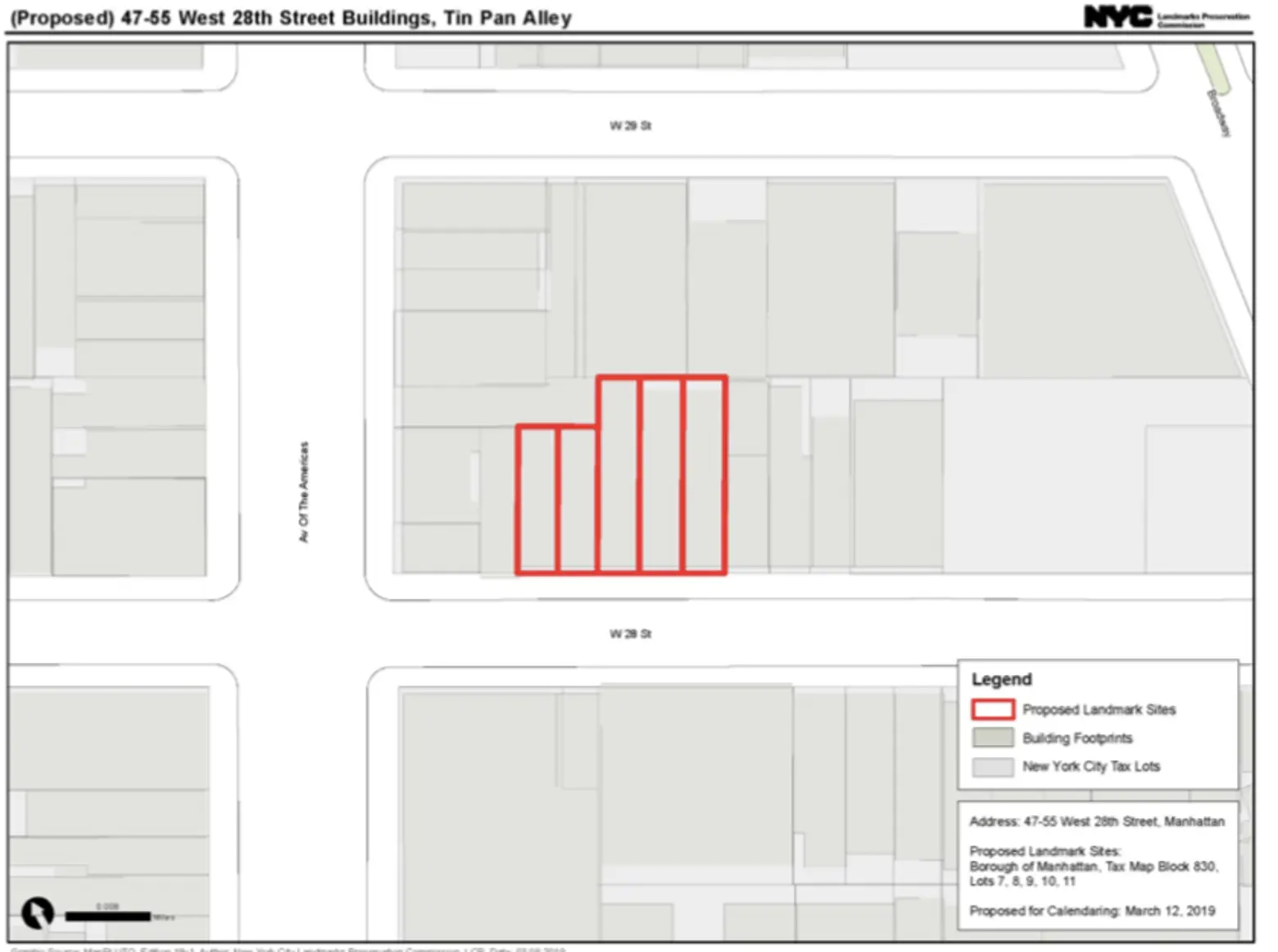

Courtesy of LPC

“I am thrilled the Commission voted to designate these culturally and historically significant buildings,” LPC Chair Sarah Carroll said in a press release. “Tin Pan Alley was the birthplace of American popular music, was defined by achievements of songwriters and publishers of color, and paved the way for what would become ‘the Great American Songbook.’ Together these five buildings represent one of the most important and diverse contributions to popular culture.”

The effort to landmark the five buildings came in 2008 when the properties were listed for sale. The buildings, located at 47, 49, 51, 53, and 55 West 28th Street, were listed for $44 million, as Lost City reported at the time. Preservationists rallied to designate the buildings in order to protect them from possible demolition. The buildings were not sold until 2013 to a developer.

The row house buildings were built between 1839 and 1859, all in the Italianate style, which includes bracketed cornices and projecting stone lintels. Although the storefronts of the buildings have been altered, the spaces above retain historic details.

During a public hearing in May about the designation of the five buildings, a majority of those testifying supported landmark status for the historic properties. But the buildings’ developer Yair Levy argued that the racist songs written during the time period should prevent the buildings from being landmarked.

“[Tin Pan Alley’s] contribution was making bigotry socially acceptable, like having these lyrics brought into the living rooms around the country and justifying the stereotypes of blacks as less than,” Levy’s attorney Ken Fisher said during the hearing.

In its designation report, the LPC acknowledged that some of the songs were “relatives of musical forms which were popular in minstrel shows.” The report reads: “Their employment of slurs and caricatures reflects systemic racism in the post-Reconstruction era and a particular lineage of racist stereotypes in American entertainment.”

Despite this, Tin Pan Alley also reflects the transition of African American and Jewish artists into the mainstream music industry. The very first work between black and Jewish composers and performers is linked to the area, including Irving Berlin, Harold Arlen, Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Noble Sissle, J. Rosamond Johnson, James Reese Europe, and many others.

“Tin Pan Alley represents important African-American musical history, and conveys our true struggles, successes and evolving partnerships with other artists toward creating a broader and more inclusive American songbook,” writer John T. Reddick, who has written about African-American and Jewish music culture in Harlem.

RELATED: