How New Yorkers responded to the 1918 Flu Pandemic

A typist wearsing a guaze mask in 1918.Via the National Archives and Records Administration

May 2018 marks the centennial of one of the world’s greatest health crisis in history—the 1918 flu pandemic. In the end, anywhere from 500,000 to 1 million people worldwide would die as a result of the pandemic. New York was by no means spared. During the flu pandemic, which stretched from late 1918 to early 1920, over 20,000 New Yorkers’ lives were lost. However, in many respects, the crisis also brought into relief what was already working with New York’s health system by 1918. Indeed, compared to many other U.S. cities, including Boston, New York suffered fewer losses and historians suggest that the health department’s quick response is largely to thank for the city’s relatively low number of deaths.

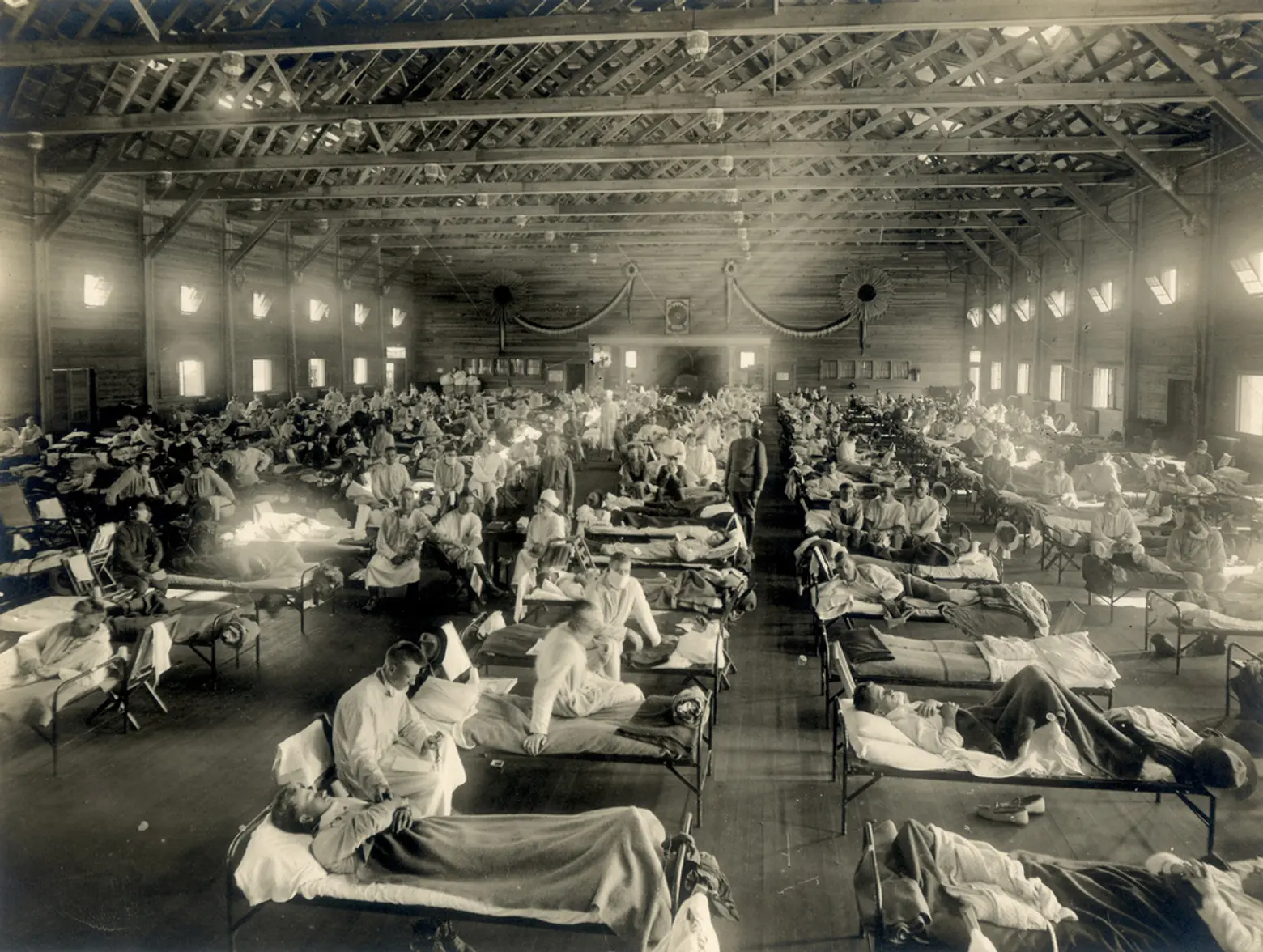

An emergency hospital during the influenza epidemic in Camp Funston, Kansas, via Wiki Commons

An emergency hospital during the influenza epidemic in Camp Funston, Kansas, via Wiki Commons

May 1918: The flu makes its first appearance

As reported in the New York Times on September 22, 1918, just as the flu was beginning to ravage the city’s population, the flu first appeared in May 1918 in Spain. While the flu would remain widely known as the “Spanish influenza,” it quickly spread to other countries across Europe, including Switzerland, France, England, and Norway. Already a global world, it wasn’t long before the flu started to travel overseas via ill passengers. As reported in the New York Times, “In August, this disease carried by ocean liners and transports, began to make its appearances in this country, and within the past two weeks the occurrences of the malady in the civilian population and among soldiers in the cantonments have increased so greatly in number that Government, State, and municipal health bureaus are now mobilizing all the forces to combat what they recognize to be an approaching epidemic.”

The Health Board urged New Yorkers to wear masks with the phrase, “Better ridiculous than dead.” Via the National Archives and Records Administration

The Health Board urged New Yorkers to wear masks with the phrase, “Better ridiculous than dead.” Via the National Archives and Records Administration

A Quick and Effective Response from New York’s Health and Housing Authorities

As Francesco Aimone argues in a 2010 article on New York’s response to the 1918 flu pandemic, although newspapers reported that the first cases of influenza came via the port on August 14, 1918, roughly 180 earlier cases of active influenza arrived on vessels in New York City between July 1 and mid-September. Indeed, as Aimone reports, “Approximately 305 cases of suspected influenza were reported throughout the voyages of 32 ships’ port health officers examined from July through September, including victims who died while at sea or recovered from their illness.” However, health officials did not discover any secondary outbreaks of influenza until after August 14, 1918.

Aimone’s study further emphasizes that despite the fact that New York City was home to an active international harbor, the city ultimately managed to contain its influenza cases through a number of measures, which included those connected to housing. Most notably, the Health Department opted for a “two-tiered approach to isolating cases of influenza.” As Health Commissioner Royal S. Copeland told The New York Times on September 19, “When cases develop in private houses or apartments they will be kept in strict quarantine there. When they develop in boarding houses or tenements they will be promptly removed to city hospitals, and held under strict observation and treated there.” While most cases were moved to hospitals, as hospital spaces filled up, the city opened other designed spaces and at one point even turned the Municipal Lodging House, the city’s first homeless shelter on East 25th Street, into a care facility for those suffering from influenza.

However, the Department of Health was not solely responsible for helping fight the spread of influenza during the 1918 pandemic. When more public health inspectors were needed, inspectors were reassigned from the Tenement House Department. Among other tasks, housing inspectors undertook a house-to-house canvas to attempt to find previously undocumented cases of flu and pneumonia.

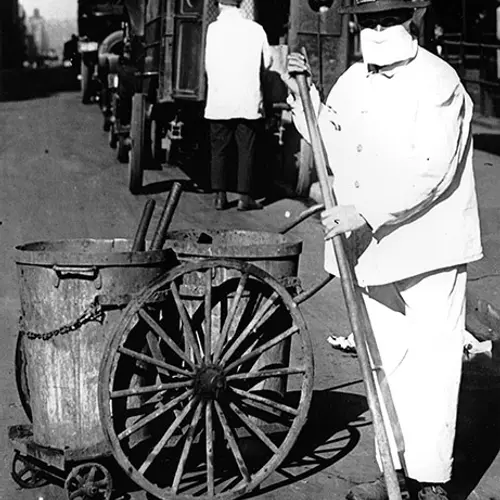

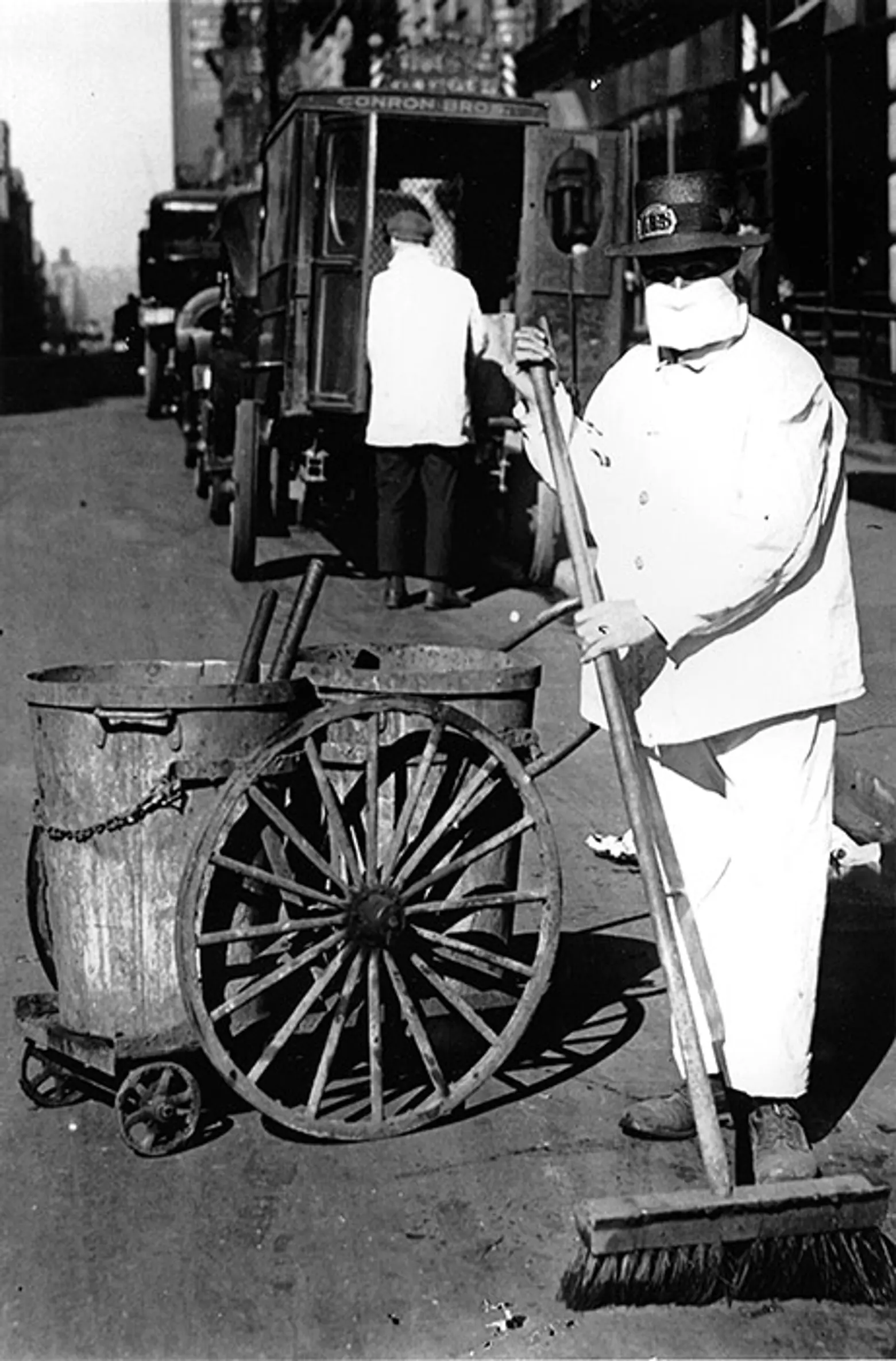

A NYC street sweeper wears a mask while working. Via the National Archives and Records Administration

A NYC street sweeper wears a mask while working. Via the National Archives and Records Administration

The Goodwill of New Yorkers

While the city’s quarantining program was generally effective, it was ultimately contingent on the goodwill and cooperation of New Yorkers. Without the proper staff to enforce isolation orders, isolation remained a voluntary measure. In essence, enforcement of the isolation orders was either self-imposed by the ill or imposed on the ill by their families. New Yorkers also helped contain the spread of influenza by abiding with the myriad of other enforcements regulating everything from when they rode public transit to their handkerchief use. In fact, close to one million leaflets were distributed during the crisis aimed at educating the public on how their everyday practices could play a key role in containing the spread of influenza.

In the end, proportionate to the population, New York City fared better than most U.S. cities with a rate of 3.9 deaths per thousand residents. Indeed, compared to the twenty largest cities in the United States, only Chicago and Cincinnati reported lower mortality rates than New York City. A combination of a well-developed health department, understanding of the link between health and housing conditions, and the goodwill of New Yorkers all played a key role in combatting the pandemic.

RELATED: