Edward Hopper’s Greenwich Village: The real-life inspirations behind his paintings

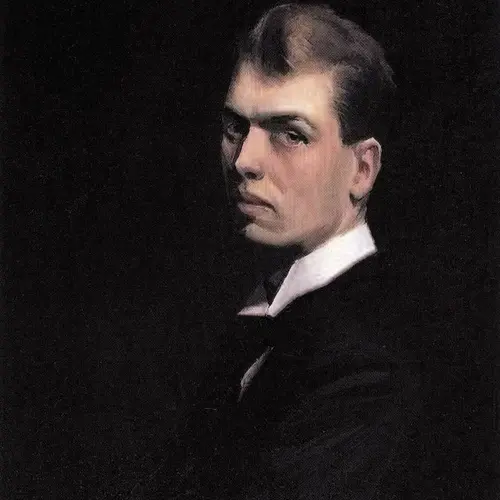

There’s no lack of artists deeply associated with New York. But among the many painters who’ve been inspired by our city, perhaps none has had a more enduring and deeper relationship than Edward Hopper, particularly with Greenwich Village. Hopper lived and worked in Greenwich Village during nearly his entire adult life, and drew much inspiration from his surroundings. He rarely painted scenes exactly as they were, but focused on elements that conveyed a mood or a feeling. Hopper also liked to capture scenes which were anachronistic, even in the early 20th century. Fortunately due to the Village’s enduring passion for historic preservation, many, if not all, of the places which inspired Hopper nearly a century ago can still be seen today – or at least evidence of them.

Early Sunday Morning (1930); courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art

One of the most evocative of Hopper’s paintings is Early Sunday Morning. The image oozes the sense of a lonely holdout, and around the time Hopper painted this classic in 1930, countless older structures like this were being or had been demolished across Greenwich Village to make way for street lengthenings and subway construction along Sixth Avenue, Seventh Avenue, and Houston Street.

Current street view of 233-235 Bleecker Street

But fortunately, it appears that for this particular image, Hopper apparently chose a building which still stands today – 233-235 Bleecker Street at Carmine Street. Constructed in the early 19th century as a coach house and residence, these wooden structures were landmarked in 2010 as part of the South Village extension of the Greenwich Village Historic District.

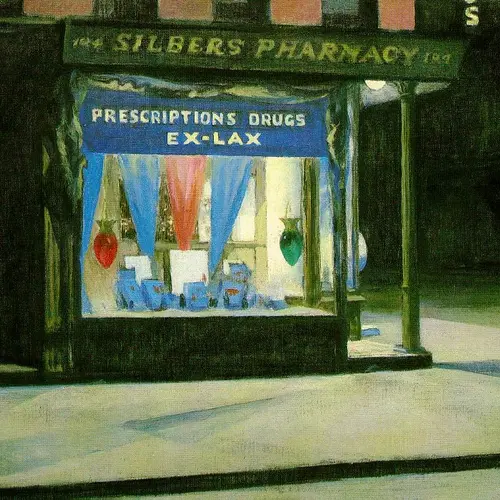

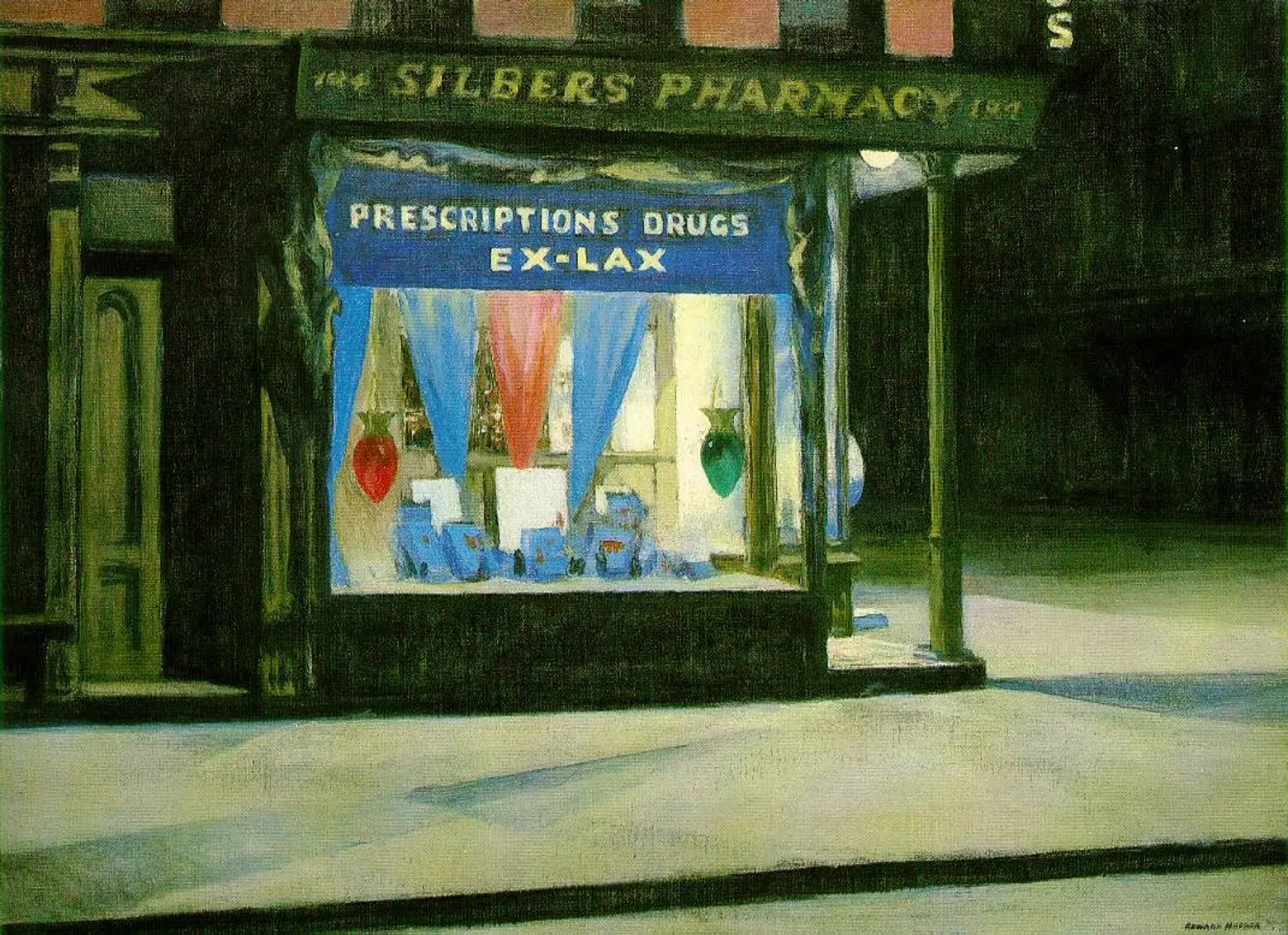

Drug Store (1927); courtesy of ibiblio

Current street view of 154 West 10th Street

Another beloved Hopper painting is Drug Store (1927). The image captures a solitary pharmacy whose light emanates in the darkness of evening on a shadowed corner. While Hopper never revealed what building he based this painting upon, considerable evidence points to 154 West 10th Street/184 Waverly Place as the likely inspiration. Not only the building but the slender cast-iron column raised above the ground, still remain. And fittingly the space is now occupied by one of the Village’s most treasured but frequently endangered institutions, the independently-owned bookstore –in this case, the beloved Three Lives.

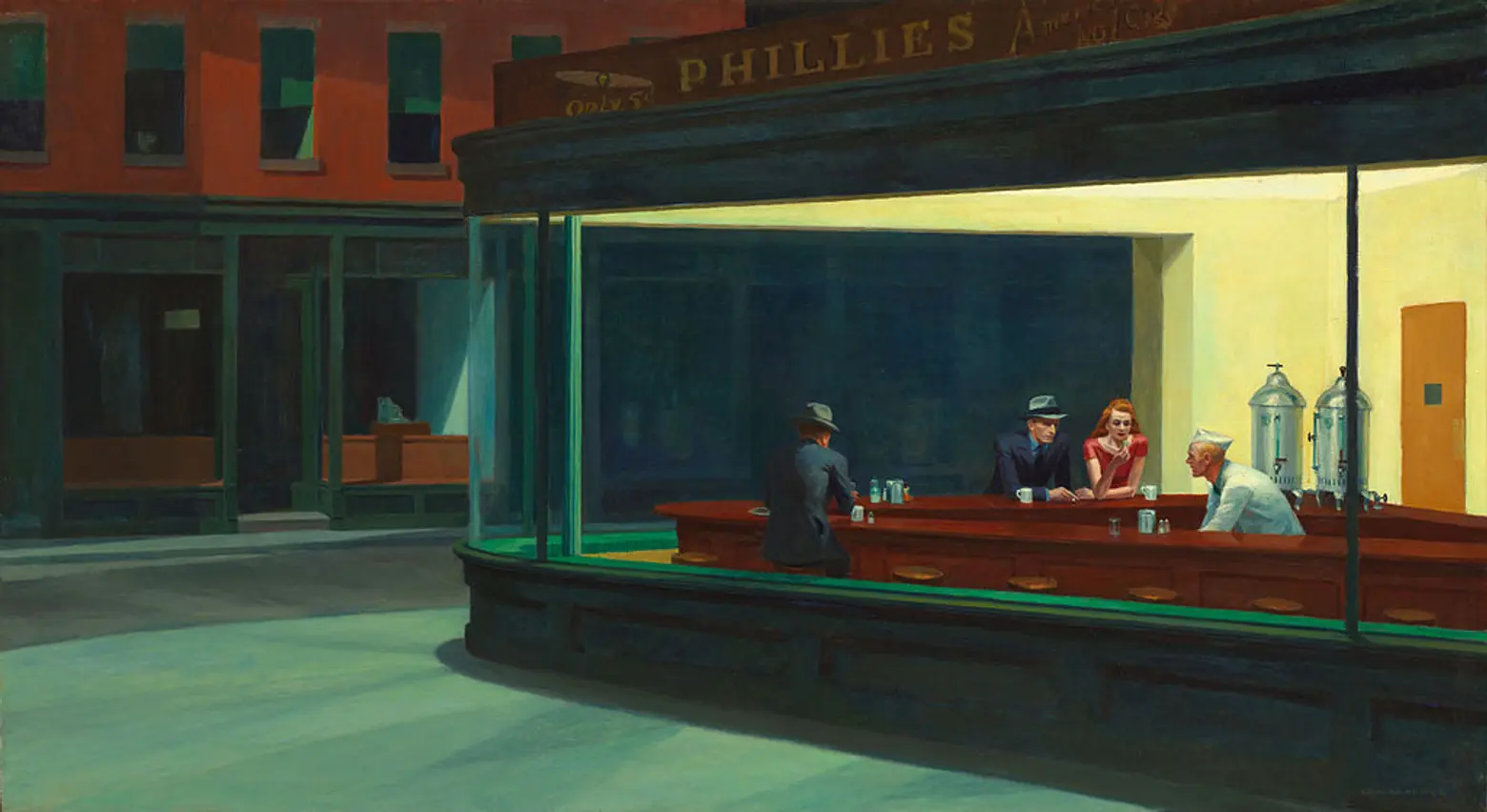

Nighthawks (1942); photo via Wikipedia

Perhaps the painting most strongly associated with Hopper is 1942’s Nighthawks. The iconic image of lonely late-night denizens of a corner diner poignantly captures the sense of isolation and detachment Hopper highlighted in urban life. It’s often supposed that the buildings in the background behind the diner include 70 Greenwich Avenue, located at the southeast corner of the intersection with 11th Street and that therefore the Nighthawks diner once stood on the triangular piece of land just south of it between Greenwich Avenue and 7th Avenue South. That lot had been an MTA parking facility until a few years ago and is now the site of an MTA ventilation plant.

Current street view of 70 Greenwich Avenue

But while Hopper may well have been inspired by 70 Greenwich Avenue for the background building in Nighthawks, to which it bears a strong resemblance, in fact, no diner ever stood in that triangular piece of land just to the south. So if 70 Greenwich Avenue is the building in the background of Nighthawks, the inspiration for the diner, while possibly nearby, never stood on that exact spot.

Records show that metal, one story triangular diners stood nearby at the time Hopper painted Nighthawks just to the south of the site at 173 Seventh Avenue South, and at 1-5 Greenwich Avenue, near Christopher Street. These were likely the inspirations for the diner itself, but certainly, one can stand at the corner of Greenwich Avenue and 7th Avenue South, with 70 Greenwich Avenue behind you, and imagine those lonely late-night diner patrons being served at the neon-lit counter.

The Sheridan Theatre (1937); via WikiArt

Sheridan Theatre at Greenwich Avenue in 1922; photo via Wikimedia

Another Hopper location where one can only imagine the scene originally depicted is just up Greenwich Avenue on the triangular plot of land bounded by 12th Street, 7th Avenue, and Greenwich Avenue. Until 1969 the grand Loew’s Sheridan Theater movie palace stood here. Like so many of the movie palaces of the era, it was torn down, in this case, to make way for a vehicle maintenance facility and equipment storage center for St. Vincent’s Hospital, which stood across 7th Avenue. When St. Vincent’s closed its doors in 2010, these facilities were demolished to make way for St. Vincent’s Memorial Park and the New York City AIDS Memorial, which now stand in their place.

New York Studio School; photo via Wikimedia

Hopper’s big break came in 1920 when he was given his first one-person show at the Whitney Studio Club on West 8th Street, which had only recently been established by heiress and arts patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Appropriately enough that building now houses the New York Studio School, which (according to its website) “is committed to giving aspiring artists a significant education that can last a lifetime.”

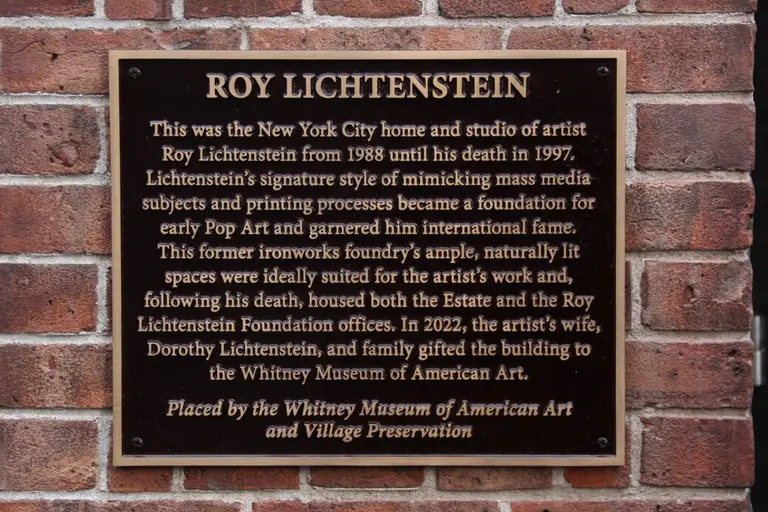

Meanwhile, the Whitney Museum, the successor to the Studio Club, has now returned to Greenwich Village on Gansevoort Street after a more than half-century absence, and its collection (“arguably the finest holding of 20th century American art in the world” according to its website) prominently features many of Hopper’s most celebrated paintings, including Early Sunday Morning.

The most tangible connection to Edward Hopper which still stands in the Village is not the inspiration for one of his paintings, but his former studio located at 3 Washington Square North. Hopper lived and painted here from 1913 until his death in 1967, and the studio itself remains intact. While not generally open to the public, tours and visits can be arranged by appointment.

Roofs, Washington Square (1926); photo via Carnegie Museum of Art

There is, however, another reminder of Hopper’s years at his Washington Square studio that one can see without a special appointment; his 1926 painting Roofs, Washington Square, which captures the unique perspective of the houses of Washington Square North as they can only be seen by a resident.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED: