17 LGBT landmarks of Greenwich Village

Last year’s Pride Parade outside the Stonewall Inn, via Wiki Commons

In about a month New York will be in the throes of celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, three nights of disturbances from June 28th to June 30th 1969, which are recognized globally as the start of the modern LGBT rights movement. But Stonewall is only one of the scores of important LGBT landmarks in Greenwich Village – the homes of people, events, businesses and institutions dating from more than a century ago to just a few years ago. Thanks to landmark designation, most of these sites still stand. Here are just some of the dazzling array of those, all still extant, which can be found in the neighborhood which is arguably the nexus of the LGBT universe.

Google Street View of 157 Bleecker Street, today a restaurant/bar called Carroll Place

Google Street View of 157 Bleecker Street, today a restaurant/bar called Carroll Place

1. The Black Rabbit and the Slide, 183 and 157 Bleecker Street

These two bars were located on a stretch of Bleecker Street south of Washington Square that was infamous for debauchery and vice during the 1890s. A newspaper account at the time referred to the Slide as the “lowest and most disgusting place on this thoroughfare” and “the wickedest place in New York.” The two bars had live sex shows and prostitution, featuring “degenerates” who cross-dressed for the entertainment of the audience or the sexual pleasure of their patrons. They were frequented by both tourists (sexual and otherwise) interested in seeing how the “other half” lived as well as “queer” and gender-non-conforming New Yorkers. Both were the subject of vice raids and vilification in the press and were closed down frequently during the “Gay 90s.” They are among the oldest known places of assemblage of LGBT people in New York City. Both buildings were landmarked in 2013 as part of the South Village Historic District which Village Preservation proposed.

Google Street View of the Church of the Village

Google Street View of the Church of the Village

2. Church of the Village/Founding of PFLAG, 201 West 13th Street

The first meeting of what came to be the organization now known as PFLAG — Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays — took place at what is now known as the Church of the Village, at 13th Street and 7th Avenue, then known as the Metropolitan-Duane United Methodist Church.

In June of 1972, Jeanne Manford, a schoolteacher from Queens, marched in the Christopher Street Liberation March, the precursor of today’s LGBT Pride Parade, with her gay son Morty to show support for her child. So many people came up to Jeanne and asked her to speak to their parents that she decided to hold a meeting for parents struggling with accepting and supporting their gay children. That meeting took place on March 26, 1973, and eventually led to the founding of PFLAG, which now has 400 chapters nationally and 200,000 members, provides resources and support to the families of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender people, and lobbies for greater understanding and equal treatment of LGBT people.

In 2013, Village Preservation partnered with PFLAG and the Church of the Village to place a plaque on the front of the church, commemorating the first meeting and founding of PFLAG having taken place there. The church is landmarked as part of the Greenwich Village Historic District.

Circa 1940 tax photo of 129 MacDougal Street, courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives

Circa 1940 tax photo of 129 MacDougal Street, courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives

3. Eve Adams’ Tea Room, 129 MacDougal Street

In 1925, Eve Kotchever (better known by her pseudonym, Eve Addams) opened her tearoom at 129 MacDougal Street. She was a Polish-Jewish lesbian immigrant known as the “queen of the third sex” and “man-hater,” and proudly reinforced this image with a sign on the door of her establishment that read “Men are admitted but not welcome”. The Greenwich Village Quill called the tearoom a place where ‘ladies prefer each other”. On June 17, 1926, the club was raided by police and Addams was charged with disorderly conduct and with obscenity for her collection of short stories, Lesbian Love. She was deported and was later said to have opened a lesbian club in Paris. Tragically after the Nazi invasion of France she was deported to Auschwitz where she was killed. In 2003 Village Preservation proposed and secured landmark designation of 129 MacDougal Street, which was also included in the South Village Historic District in 2013.

St. Joseph’s Church Via Flickr cc

St. Joseph’s Church Via Flickr cc

4. First Meeting of the Gay Officer’s Action League/St. Joseph’s Church, 371 Sixth Avenue

St. Joseph’s is the oldest extant intact Catholic Church in New York City, built in 1833. But In 1982, the first meeting of the Gay Officers Action League (GOAL)–now a 2,000 member organization with 36 chapters across the country representing LGBTQ persons in law enforcement and criminal justice professions–was held in the basement. By 1982, the church had become known as one of the most welcoming and accepting Catholic churches in the city for gay congregants, and to this day the church holds a special mass during LGBT Pride Month in June to commemorate those lost to AIDS.

The GOAL meeting was organized by Sergeant Charles H. Cochrane. In 1981, Cochrane became the first NYPD officer to publicly reveal that he was gay when he testified in front of the New York City Council in support of the gay rights bill. Cochrane’s public declaration was historic and directly followed testimony by the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association opposing the legislation, which included the assertion that there were no gay police officers in the NYPD. Though Cochrane’s testimony received a standing ovation from supporters and he reportedly receiving a positive response from fellow officers to his coming out, the gay rights bill was defeated and did not become law until 1986.

Eleven officers attended GOAL’s first meeting at St. Joseph’s Church, although it was uncommon and even dangerous for police officers to come out. After his death from cancer in 2008, the corner of Sixth Avenue and Washington Place in front of the church was named in honor of Cochrane. Since GOAL’s establishment, hundreds of NYPD officers have come out, many of whom march in the annual LGBT Pride March. While many NYPD officers stationed at the annual pride march would routinely turn their backs when GOAL would march by in their early years, the NYPD marching band now marches along with GOAL each year in the Pride Parade.

5. Lorraine Hansberry Residences, 337 Bleecker Street and 112 Waverly Place

Born in 1930, Lorraine Hansberry was a playwright and activist most commonly associated with Chicago, despite attending school and living much of her life in Greenwich Village. She first attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison but left in 1950 to pursue her career as a writer in New York City. She moved to Harlem in 1951, attended the New School in the Village, and began writing for the black newspaper Freedom.

In 1953, she married Robert Nemiroff, and they moved to Greenwich Village. It was during this time, while living in an apartment at 337 Bleecker Street, that she wrote “A Raisin in the Sun,” the first play written by a black woman to be performed on Broadway. The play brought to life the challenges of growing up on the segregated South Side of Chicago, telling the story of a black family’s challenges in trying to buy a house in an all-white neighborhood. Hansberry separated from Nemiroff in 1957 and they divorced in 1964, though they remained close for the remainder of her life.

With the money she made from “Raisin,” Hansberry purchased the rowhouse at 112 Waverly Place, where she lived until her death. It was revealed in later years that Hansberry was a lesbian and had written several anonymously published letters to lesbian magazine The Ladder, discussing the struggles of a closeted lesbian. She was also an early member of the pioneering lesbian activist group the Daughters of Bilitis. Sadly, she died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 34.

Both buildings are landmarked as part of the Greenwich Village Historic District. In 2017, Village Preservation placed a plaque on Hansberry’s Waverly Place home commemorating her residence there.

99 Wooster Street today, courtesy of Village Preservation

99 Wooster Street today, courtesy of Village Preservation

6. (former) Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse, 99 Wooster Street

The building at 99 Wooster Street was built in 1881 as a New York City firehouse. But by the early 1970s it was abandoned, in the (then) largely deserted southern reaches of what had only recently come to be known as Soho. The empty firehouse soon became the home of boisterous parties, meetings, and political organizing when the Gay Activists Alliance, one of the most highly influential LGBT groups of the post-Stonewall era, took over the space in 1971. Founded in 1969 by Marty Robinson, Jim Owles, and Arthur Evans, the group was an offshoot of the Gay Liberation Front. Their location at 99 Wooster Street became the first gay and lesbian organizational and social center in New York City. Their “zaps” and face-to-face confrontations were highly influential to other activist and political groups. In 1974, they were targeted by an arson fire and subsequently were forced to cut back on functions. They officially disbanded in 1981.

In 2014, Village Preservation proposed this site, along with the Stonewall Inn and the LGBT Community Center, as the first LGBT landmarks in New York City. The Stonewall was landmarked in 2015, and the proposal to landmark the GAA Firehouse and LGBT Community Center will be heard by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on June 4.

LGBT Community Center via Flickr cc

LGBT Community Center via Flickr cc

7. LGBT Community Services Center, 208 West 13th Street

Housed in a former public school built in 1869 and 1899, the LGBT Community Center has been a home and resource hub for the LGBT community in New York City since its founding in 1983. The center celebrates diversity and advocates for justice and opportunity. It served as various types of schools for over a century and was sold to the Lesbian & Gay Services Center, Inc. in 1983. Today, it has grown to become the largest LGBT multi-service organization on the East Coast and the second largest in the world. Other organizations that have been located here (or got their start here) include SAGE (Senior Action in a Gay Environment), the Metropolitan Community Church (an LGBT congregation), the AIDS activist group ACT UP, and GLAAD (Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation). As mentioned above, the proposal to landmark the LGBT Community Center will be heard by the LPC on June 4.

8. National Gay Task Force original offices, 80 Fifth Avenue

The National Gay Task Force (now called the National LGBTQ Task Force) was founded in 1973 and was originally located in the building at 80 5th Avenue. The founding members of the task force, including Dr. Howard Brown, Martin Duberman, Barbara Gittings, Ron Gold, Frank Kameny, Natalie Rockhill, and Bruce Voeller, knew it was time to create change on a national level. Among its early accomplishments, the Task Force helped get the federal government to drop its ban on employing gay people, helped get the American Psychiatric Association to drop homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses, and arranged the first meeting between a sitting U.S President (Jimmy Carter) and a gay advocacy group. The Task Force remains a social justice advocacy non-profit organizing the grassroots power of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. Also known as The Task Force, the organization supports action and activism on behalf of LGBT people and advances a progressive vision of liberation.

The only site on this list not currently landmarked, Village Preservation proposed this building for designation in 2018 as part of a historic district proposal for the area south of Union Square.

9. Murray H. Hall Residence, 457 Sixth Avenue

Murray Hall was a Tammany Hall politico and bail bondsman whose LGBT connection was only revealed, scandalously, after his death. Born about 1841, it is believed that Hall was born as Mary Anderson in Scotland, and by around age 16 began dressing as a man. He took the name John Anderson and married a woman. However, when his wife exposed his birth sex to the police after his infidelity, he fled to the United States, where he took the name Murray Hall.

Here he married a schoolteacher and became active in the Tammany Hall political machine, which assisted with his bail bonds work and an employment agency he founded. According to the New York Times, he was known as a “man about town, a bon vivant, and all-around good fellow,” fond of poker and pool who socialized with the leading local political figures of the day. Only when he died did a doctor reveal his birth sex, which became the subject of worldwide notoriety and attention. The building at 457 Sixth Avenue, where he and his wife lived until his death, was located just north of the Jefferson Market Courthouse (now library) where he often worked and is landmarked part of the Greenwich Village Historic District.

The Oscar Wilde Bookshop in 2008, via Flickr cc

The Oscar Wilde Bookshop in 2008, via Flickr cc

10. Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, 15 Christopher Street

The Oscar Wilde Bookshop originally opened in 1967 at 291 Mercer Street as the first gay bookstore in the world (that building has since been demolished), a full two years before the Stonewall Riots. Owner Craig Rodwell stocked his shelves with literature by gay and lesbian authors and refused to stock pornography of any kind, despite having a limited selection of materials. The store became a meeting place for the LGBT community and served as the location for the organizing meetings for the first Pride Parade in the 1970s.

The shop later moved to 15 Christopher Street and was bought by Bill Offenbaker, and later, Larry Lingle. The final owner was Kim Brinster, the longtime manager of the bookstore. However, citing the Great Recession and competition from online booksellers, the bookstore finally closed its doors on March 29, 2009, part of a wave of closures of brick and mortar bookstores in the early 2000s. Since its closing, the Oscar Wilde Bookshop has been called “clearly pioneering” as it demonstrated for the first time that it was possible to own a bookstore, however small, that catered to a gay clientele. The building is located within the Greenwich Village Historic District.

11. Ramrod Bar, 394 West Street

One of the most shocking and visible manifestations of the backlash against increased gay visibility in the 1980s was the brutal shooting and massacre that took place outside the Ramrod Bar on November 19, 1980. Using two stolen handguns, a deranged and homophobic former NYC Transit Authority cop named Ronald K. Crumpley opened fire on two gay men outside a deli on the corner of Washington and 10th Streets. They avoided getting shot by ducking behind parked cars.

Then he moved onto the Ramrod Bar at 394West Street between 10th and Christopher, two blocks away, where he emptied his Uzi’s extended, 40-round magazine into the crowd. Killed instantly was Vernon Kroening, an organist at the nearby St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church. Jorg Wenz, who was working as a doorman at the Ramrod, died later that day at St. Vincent’s Hospital. Four other men were shot and injured at the scene. Crumpley then shot and injured two more men at Greenwich and 10th Streets, where he was apprehended. According to a 2016 NY Times article, a vigil drew 1,500 mourners to Sheridan Square after the crime spree. The gay press reported at the time “there were few, if any, calls for the blood of Ronald Crumpley… Anger was directed at the system which treats gay people as a subhuman species.”

The Ramrod was one of the dozens of bars, clubs, and other establishments that catered to LGBT people in the West Village in the heyday of gay life in Greenwich Village between the Stonewall Riots and the onset of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. It was located in a three-story brick Greek Revival structure built in 1848. In 2006, Village Preservation got this and surrounding buildings landmarked as part of the Weehawken Street Historic District.

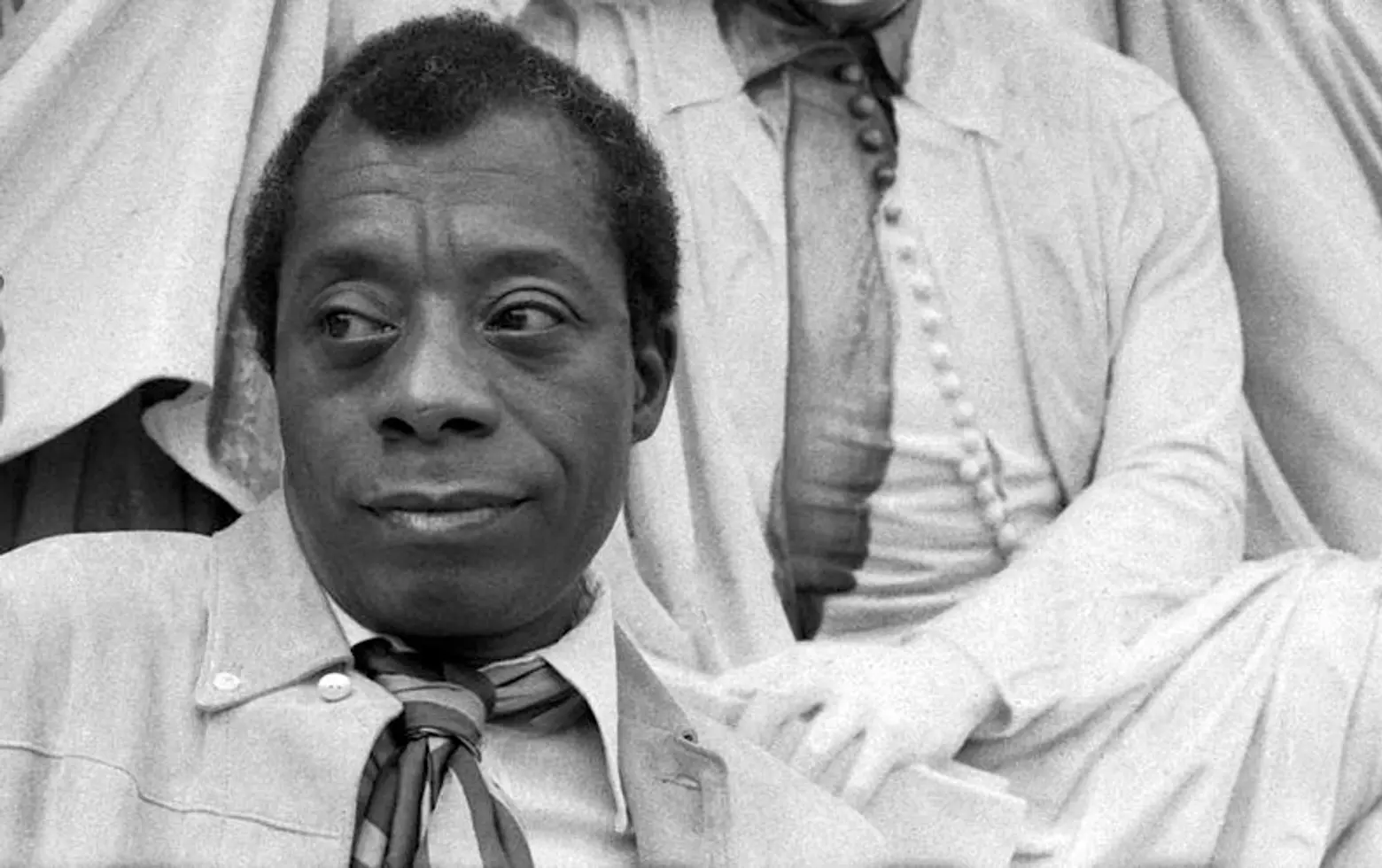

Photo of James Baldwin via Wikimedia

Photo of James Baldwin via Wikimedia

12. James Baldwin Residence, 81 Horatio Street

James Baldwin was born in Harlem in 1924 and became a celebrated writer and social critic in his lifetime, exploring complicated issues such as racial, sexual, and class tensions, as a gay African-American man. Baldwin spent some of his most prolific writing years living in Greenwich Village and wrote of his time there in many of his essays, such as “Notes of a Native Son.” Many of Baldwin’s works address the personal struggles faced by not only black men but of gay and bisexual men, amid a complex social atmosphere. His second novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” focuses on the life of an American man living in Paris and his feelings and frustrations surrounding his relationships with other men. It was published in 1956, well before gay rights were widely supported in America. His residence from 1958 to 1963 was 81 Horatio Street. A historic plaque memorializing his time there was unveiled by Village Preservation in 2015.

13. Portofino Restaurant, 206 Thompson Street

This Italian restaurant was a discreet meeting place frequented on Friday evenings by lesbians in the 1950s and 60s. The 2013 groundbreaking Supreme Court decision that overturned the federal Defense of Marriage Act had its roots here in the 1963 meeting of Edith S. Windsor and Thea Clara Spyer. Windsor and Spyer began dating after meeting at Portofino in 1963. Spyer proposed in 1967 with a diamond brooch, fearing Windsor would be stigmatized at work if her colleagues knew about her relationship. The couple married in Canada in 2007 and when Spyer died in 2009, she left her entire estate to Windsor. Windsor sued to have her marriage recognized in the U.S. after receiving a large tax bill from the inheritance, seeking to claim the federal estate tax exemption for surviving spouses.

The Defense of Marriage Act was enacted on September 21, 1996, and defined marriage for federal purposes as the union of one man and one woman, and allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages granted under the laws of other states. United States v. Windsor, which was decided on June 26, 2013, was a landmark civil rights case in which the Supreme Court held that restricting U.S. federal interpretation of “marriage” and “spouse” to apply only to opposite-sex unions is unconstitutional. It helped lead to the legalization of gay marriage in the U.S. On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that state-level bans on same-sex marriage are unconstitutional. Windsor and Spyer also lived at 2 Fifth Avenue and 43 Fifth Avenue. 206 Thompson Street was landmarked as part of the South Village Historic District proposed by Village Preservation in 2013.

Google Street View of Julius’ today

Google Street View of Julius’ today

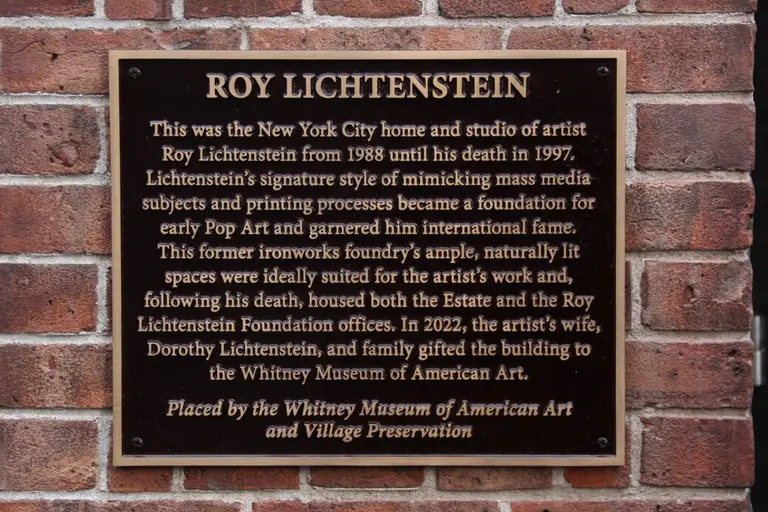

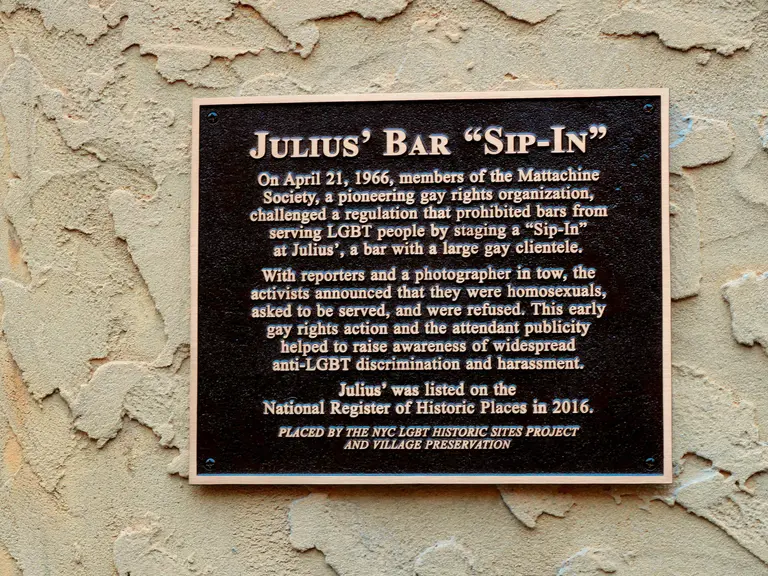

14. Julius’ Bar, 159 West 10th Street

Housed in a building which dates to 1826 and in a space that has served as a bar since the Civil War, Julius’ has been serving a predominantly gay clientele since at least the 1950s, making it currently the city’s oldest gay bar. But its claim as one of the most important LGBT landmarks extends far beyond that. In 1966, the Mattachine Society, an early LGBT rights organization, set about to challenge New York State regulations allowing bars to be closed for serving alcohol to gay people or allowing same-sex kissing or hand-holding. On April 21, these activists went to Julius’ Bar, which was popular among gay people but, like many “gay bars” at the time, required a level of secrecy by gay patrons or risked being shut down. Inspired by the “sit-ins” which had been taking place across the South, the activists decided to stage a “sip in.”

Identifying themselves as homosexuals, the protestors asked to be served a drink. In an iconic moment captured by Village Voice photographer Fred W. McDarrah which encapsulated the repression of the time, the bartender refused to serve the men, covering their bar glasses (less sympathetic coverage in the New York Times appeared under the headline “Three Deviates Invite Exclusion By Bars”). This action led to a 1967 New York State court decision striking down rules allowing bars to be shuttered simply for serving gay people, paving the way for greater freedom from harassment and abuse by LGBT people, and set the stage for future progress.

In 2012, Julius’ was ruled eligible for the State and National Registers of Historic Places, at a time when only two sites in the entire country were listed on the State and National Registers for LGBT historic significance (one of which was Stonewall). In 2014, Village Preservation proposed Julius’ for individual landmark designation along with the Stonewall Inn and the GAA Firehouse and LGBT Community Center. Of the four, it is the only one which the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission has thus far refused to consider.

Photo of the Chase Manhattan Bank at 450 Avenue P taken in 1975 by Larry Fendrick, who claims he was witness to the original event three years earlier. Via Wiki Commons.

Photo of the Chase Manhattan Bank at 450 Avenue P taken in 1975 by Larry Fendrick, who claims he was witness to the original event three years earlier. Via Wiki Commons.

15. John Stanley Wojtowicz and Ernest Aron Residence, 250 West 10th Street

On December 4th, 1971, John Stanley Wojtowicz married Ernest Aron, in what Mr. Wojtowicz described as a Roman Catholic ceremony. At the time, the two lived together at 250 West 10th Street, then a single room occupancy hotel. This event might be considered noteworthy for taking place nearly four decades before the legalization of gay marriage in New York and across the nation. But this particular Greenwich Village gay wedding is also noteworthy for having precipitated events that led to perhaps the most fabled botched bank robbery in New York City history, immortalized in one of the most acclaimed and iconic American films of the 1970s.

On August 22, 1972, John Wojtowicz, Salvatore Naturile, and Robert Westenberg entered a bank in Gravesend, Brooklyn with the intention of robbing it. However, very little went according to plan. Westenberg fled the robbery before it even began when he saw a police car nearby. The bulk of the bank’s money had already been picked up by armored car and taken off site, leaving a mere $29,000 on hand. As they were about to leave, several police cars pulled up outside the bank, forcing John and Sal back inside. They ended up taking the seven bank employees hostage for 14 hours. What made this attempted robbery so notable, however, was more than just bad planning and bad luck. An unlikely bond formed between the robbers and the bank teller hostages (Wojtowicz was a former bank teller himself). The robbers made a series of demands of the police and FBI that included everything from pizza delivery to a jet at JFK to take them to points unknown. However, perhaps most unusual was when word leaked out that Wojtowicz was robbing the bank to pay for a sex change operation for Ernest Aron, and Ernest (who would later, in fact, get the operation and become Elizabeth Eden) was even brought to the site of the hostage stand-off in an attempt to get the robbers to give up.

Throughout all of this, Wojtowicz became an unlikely media-celebrity, an anti-hero who taunted the police with shouts of “Attica” and seemed to champion the plight of the bank tellers and fast food delivery workers with whom he interacted. A growing crowd gathered and TV cameras swarmed to the site. Unsurprisingly, this did not have a happy ending. En route to JFK, Salvatore Naturile, who was only 19, was shot and killed by the FBI. Wojtowicz claims that he made a plea deal which the court did not honor, and he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, of which he served 14.

Given the intense interest in the robbery and the improbable cult-hero status Wojtowicz achieved, the story did not end there. A story in Life Magazine about the incident called “The Boys in the Bank” (an allusion to the 1968 Mart Crowley play, “The Boys in the Band,” a landmark of gay theater) by Peter F. Kluge and Thomas Moore became the basis for the 1975 feature film “Dog Day Afternoon,” directed by Sidney Lumet and written by Frank Pierson. Al Pacino, in what came to be one of his most celebrated roles, played Wojtowicz, and John Cazale played Naturile (ironically, both starred in “The Godfather,” which Wojtowicz had seen the morning of the robbery and upon which he based some of his plans). The movie garnered six Academy Award nominations and became an icon of ’70s cinema.

16. Seven Steps Bar, 92 West Houston Street

The Seven Steps was a below-ground bar, one of several lesbian bars that operated in the Village in the postwar years (others included the Sea Colony Bar & Restaurant at 48-52 Eighth Avenue, the Swing Rendezvous at 117 MacDougal Street, the Bagatelle at 86 University Place, the Pony Stable Inn at 150 West 4th Street, and the Duchess/Pandora’s Box on Sheridan Square). Most catered to a largely working-class crowd, which generally adhered to strict “butch/femme” roles for lesbians – a dichotomization which changed dramatically with the advent of second-wave feminism in the 1960s and after the Stonewall Riots.

The Seven Steps is perhaps best remembered for its connection to one of the most notorious murders in New York City history, one which spoke, silently, to the enforced secrecy and erasure that lesbians faced in this era. It was at this bar that Kitty Genovese met Mary Ann Zielonko, who would become her lover and the woman to whom she was returning home in Kew Gardens, Queens when she was brutally assaulted and murdered in March of 1964. One of the most sensationalized, discussed, and analyzed murders of the 20th century, from which the notion of “bystander syndrome” was wrought, Kitty Genovese’s lesbianism or the fact that she was murdered outside the home she shared with her girlfriend, was never mentioned, and Zielonko was not even allowed to attend her funeral. Only in much later years was this element of the Kitty Genovese’s story revealed. The building in which the bar was located still exists, and was landmarked in 2013 as part of the South Village Historic District Village Preservation proposed and secured.

Photo by Diana Davies, Stonewall Inn, 1969, courtesy of New York Public Library

Photo by Diana Davies, Stonewall Inn, 1969, courtesy of New York Public Library

17. The Stonewall Inn, 51-53 Christopher Street

If there is one site connected to LGBT history that anyone knows, it’s the Stonewall Inn, where for three nights in late June, bar patrons and their supporters fought back against routine police harassment and began a revolution in thought, activism, and culture that continues to ripple today. The events that took place in and around the Stonewall are marked with parades, marches, and celebrations in cities and countries across the globe. In 1999, Village Preservation was the co-applicant for having the Stonewall listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places, the first site ever listed for connection to LGBT history, and in 2015 led the successful campaign to have the building receive individual landmark designation – the first time the City of New York had done so for an LGBT historic site.

In contrast to the broad recognition that those events receive now, the three nights of disturbances following the police raid of the mafia-operated bar (almost all gay bars at the time were mafia-run, as they were considered illegal and subject to police harassment) received scant attention at the time, and the little it did was largely negative. The Daily News’ headline was “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Stinging Mad,” while even the newsletter of the stodgier and more conservative gay activist group the Mattachine Society somewhat derisively referred to it as the “hairpin drop heard round the world.”

Stonewall Inn today, via Wiki Commons

Stonewall Inn today, via Wiki Commons

A few other lesser-known facts about the Stonewall Inn: it originally occupied 51 and 53 Christopher Street, while the present-day Stonewall Bar only occupies 53. In fact, the present-day Stonewall Bar has no real connection to the original Stonewall other than location and name; the original Stonewall closed in 1969 just after the riots and the spaces were rented to a series of businesses, none of them gay bars, for nearly 20 years (ironically this was during a period when gay bars proliferated throughout Greenwich Village and several dozen were located within just a few blocks of here). The present-day Stonewall Bar began operating in 53 Christopher Street in 1991.

Another piece of little-known LGBT history about the building: Lou Reed lived in the apartment above the what had been the Stonewall Bar in the 1970s, part of that time with girlfriend Rachel Humphreys, a transgender woman. During his time living at 53, Reed produced many iconic records which typically referenced or commented upon the scene he would see outside his apartment, which included the drag queens, leather daddies, and gay men who strolled along Christopher Street in the 1970s.

+++

For more LGBT historic sites in Greenwich Village, see Village Preservation’s Civil Rights and Social Justice Map, and the LGBT Sites Tour on our Greenwich Village Historic District 50th Anniversary Map.

RELATED:

- VIDEO: Tour historic LGBT sites in Greenwich Village, from Stonewall and beyond

- Exploring NYC’s historic gay residences beyond Greenwich Village

- 8 things you didn’t know about LGBT history in NYC

- PHOTOS: NYC’s first LGBTQ monument opens in Greenwich Village

+++

This post comes from Village Preservation. Since 1980, Village Preservation has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid