The history of New York City’s original rooftop bars

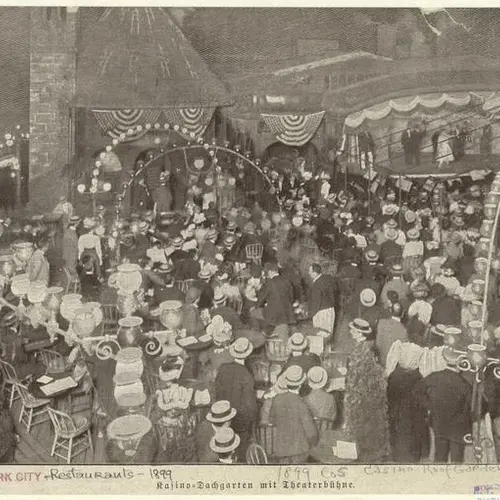

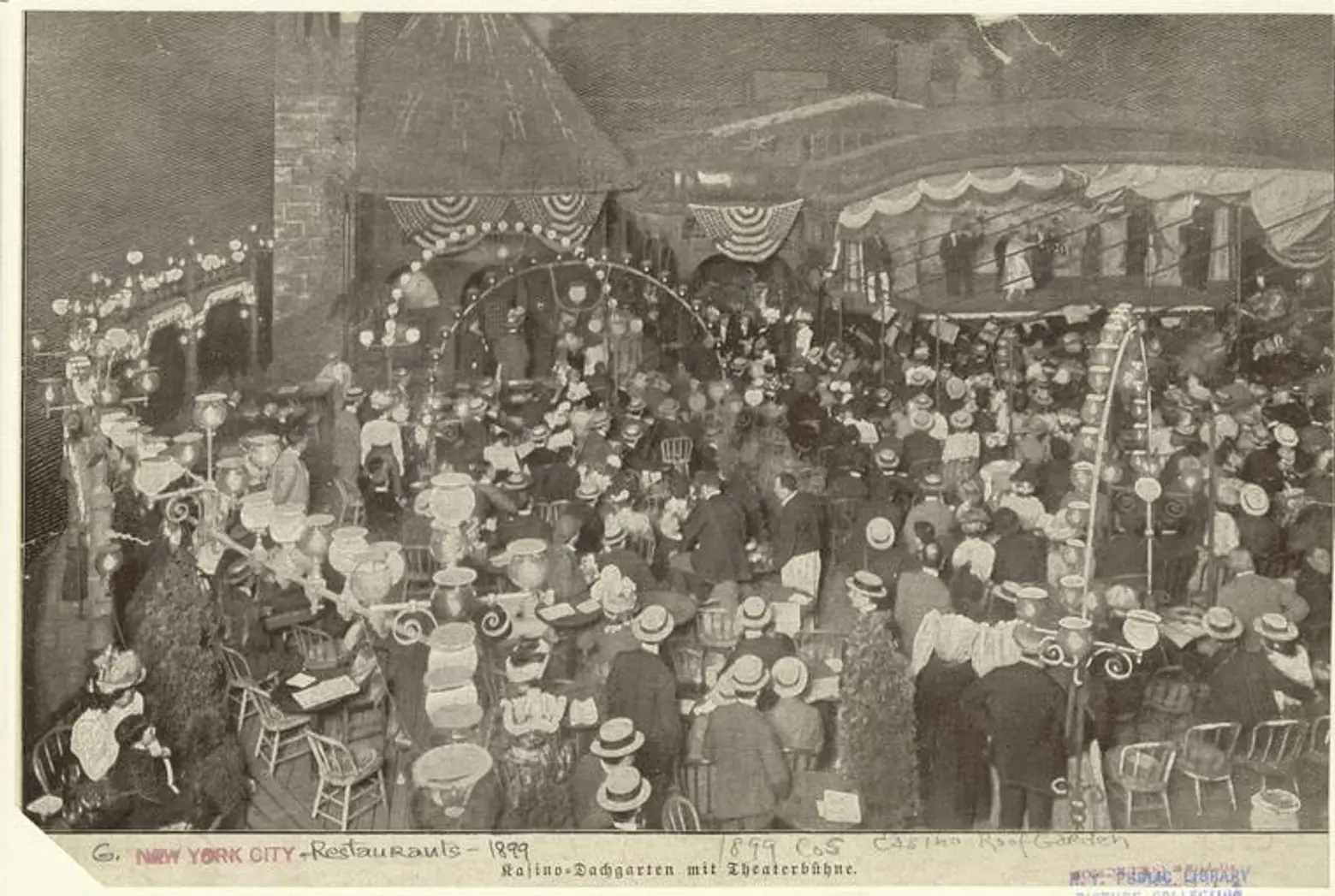

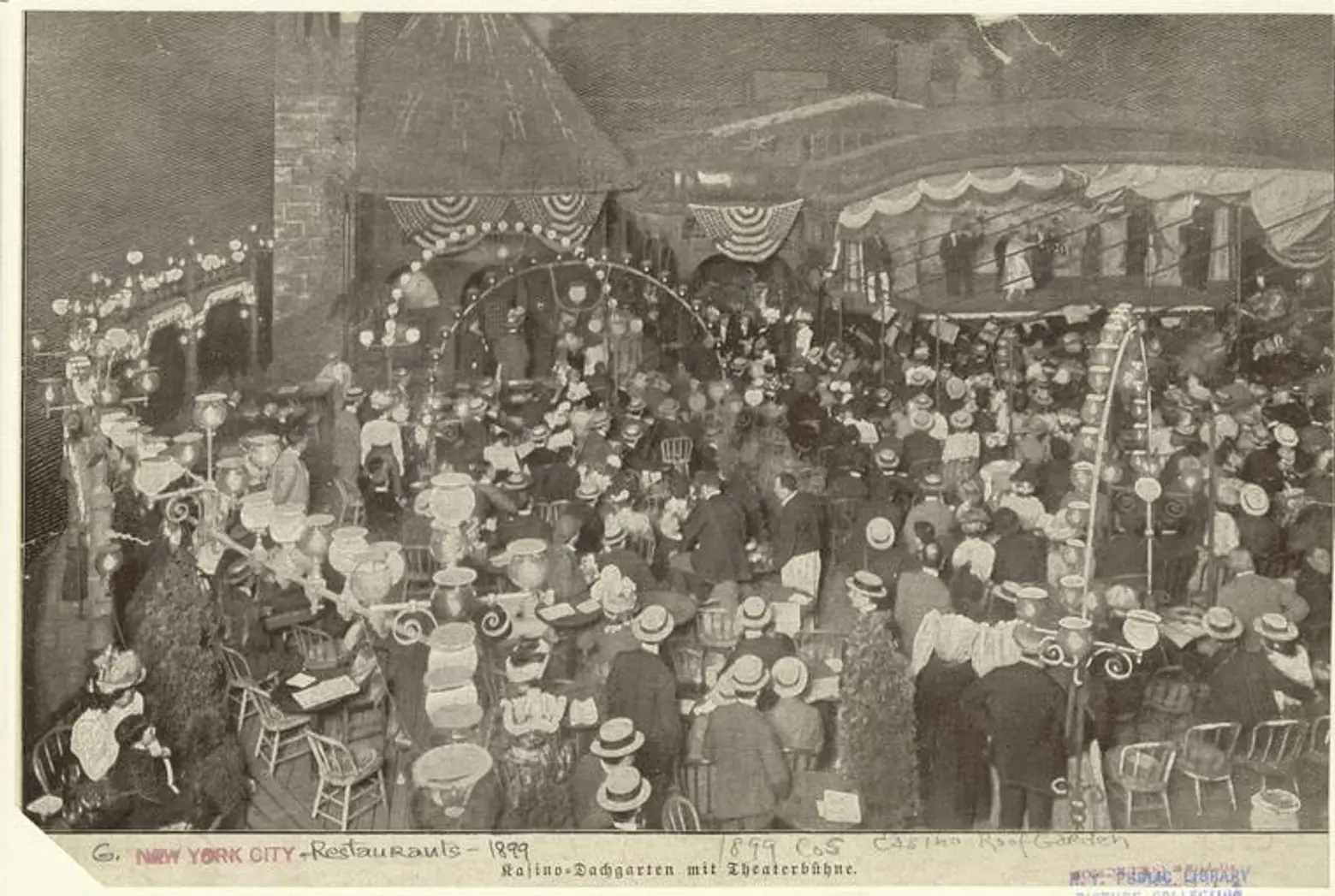

Casino Roof Garden, 1899 via NYPL Digital Collections

How many summer evenings have you spent at a rooftop bar? While the rooftop bar was indeed born and bred in New York City, it’s nothing new. Even before New York was a city of skyscrapers, denizens of Gotham liked to take their experiences to vertical extremes. And when it comes to partying, New Yorkers have been conquering new heights, drink in hand, since 1883. That year, impresario Rudolf Aronson debuted a roof garden on the top of his newly built Casino Theater on 39th Street and Broadway. The rooftop garden was soon a Gilded Age phenomenon, mixing vaudeville and vice, pleasure and performance, for well-heeled Bon-Vivants who liked to spend their summers high above the sweltering streets.

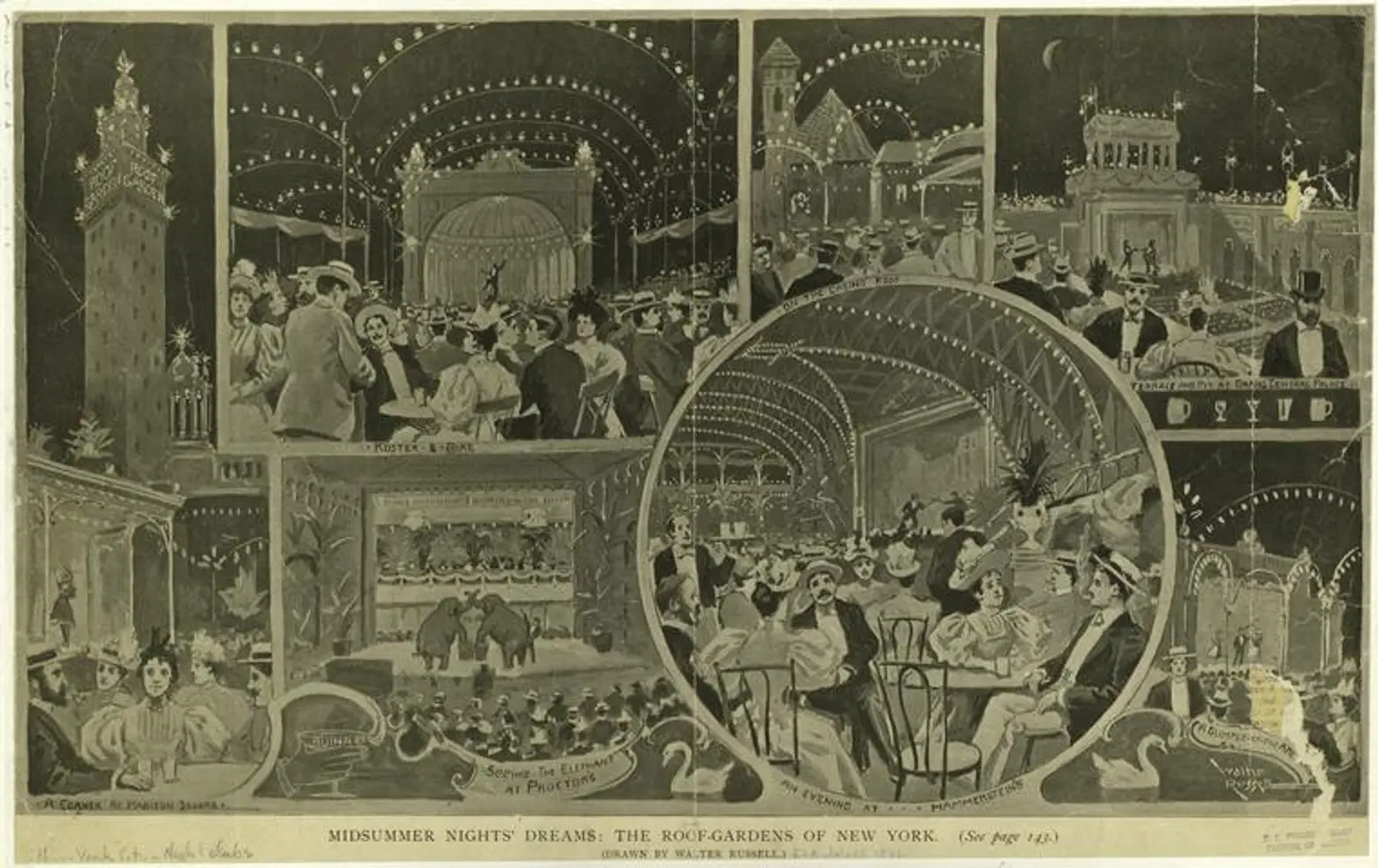

“Midsummer Night’s Dream: The Roof-Gardens of New York,” 1896, via NYPL Digital Collections

In June 1905, The New York Times reported a summer scene that might feel familiar to current city-dwellers:

Far above the street level last night the bands played while toes twinkled and cool glasses clinked. Down below, the wayfarers, pausing for a moment, caught fleeting sounds of merriment above, and familiar sounds of the summer night were wafted from the roofs.

But the similarity ends there. This was not a quick, post-work gin-and-tonic in the balmy August heat before you go home and do your laundry. There was nothing workaday about New York’s original rooftop bars. With seating for hundreds, variety shows, live animals, and an endless variety of themes and decorative motifs, the sheer scale, opulence and spectacle available in New York’s roof gardens was far beyond anything you’ll find around town today.

Casino Roof Garden, 1899 via NYPL Digital Collections

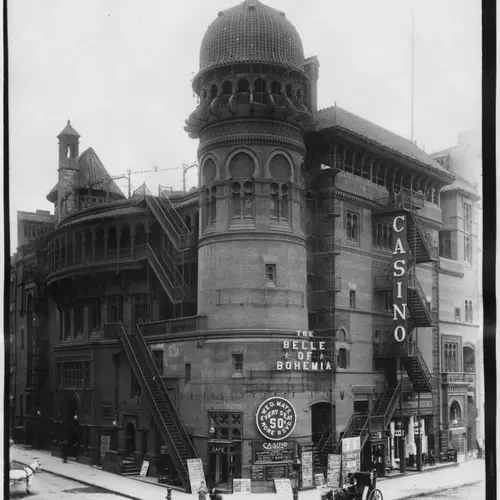

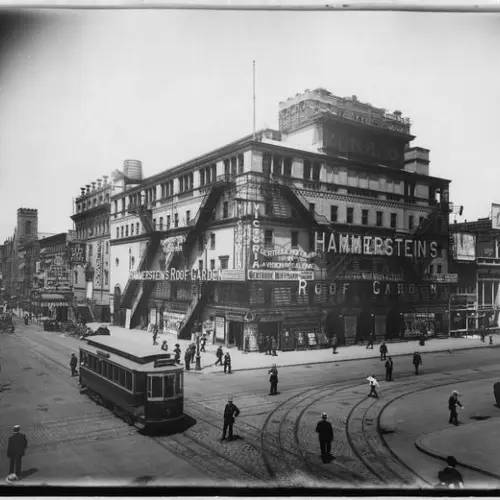

The Ancestral home of the rooftop bar, the Casino Theater, was one of the finest examples of Moorish architecture in the nation, and it was the first theater to be entirely lit by electric light; the roof of the Belasco Theater featured a working Dutch farm, pond, and windmill; The Paradise Garden atop Hammerstein’s Victoria theater was modeled on the Grand Promenades of Monte Carlo; The roof of Stanford White’s Madison Square Garden transported guests to the Italian Renaissance, and the New York Theater’s “Jardin de Paris,” where Florenz Ziegfeld debuted his Follies, had an obvious French inflection.

Casino Theater, southeast corner of Broadway and 39th St., 1900, via Wiki Commons

Casino Theater, southeast corner of Broadway and 39th St., 1900, via Wiki Commons

Gilded Age roof gardens were huge, blockbuster entertainment venues run by the greatest theater impresarios the world has ever known. Oscar Hammerstein, Florenz Ziegfeld and other titans of entertainment spared no expense for opening night.

Hammerstein’s Roof Garden (Victoria Theater), 7th Avenue and 42nd Street, ca. 1908 via Wiki Commons

Hammerstein’s Roof Garden (Victoria Theater), 7th Avenue and 42nd Street, ca. 1908 via Wiki Commons

According to the Times, for the opening of the 1905 Summer Season:

Oscar Hammerstein’s Paradise Roof Gardens had thrown open their gates and were giving the first comers of the roof season a merry welcome. Everything had been dressed up for the occasion in a new garb, the auditorium was dazzling in white paint and countless incandescents, the old mill and little cluster of buildings were gay in festive colors, and there were new ducks, a new monkey, a new goat and a new cow.

The roof gardens also provided entertainment to match the sumptuous surroundings. For example, the Follies of 1907 provided “twenty musical numbers and many vaudeville acts” every evening at the Jardin de Paris. Audiences were so accustomed to high drama in rooftop settings, that when the architect Stanford White was shot at point-blank range on the top of his own Madison Square Garden in 1906, other patrons did not immediately understand that he was hurt, for they assumed it was simply a stunt, put on as part of the evening’s entertainment.

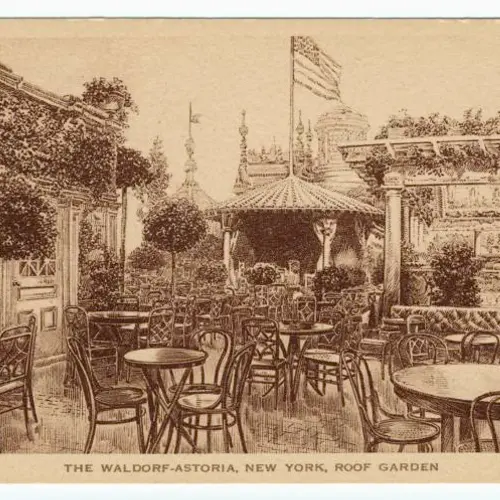

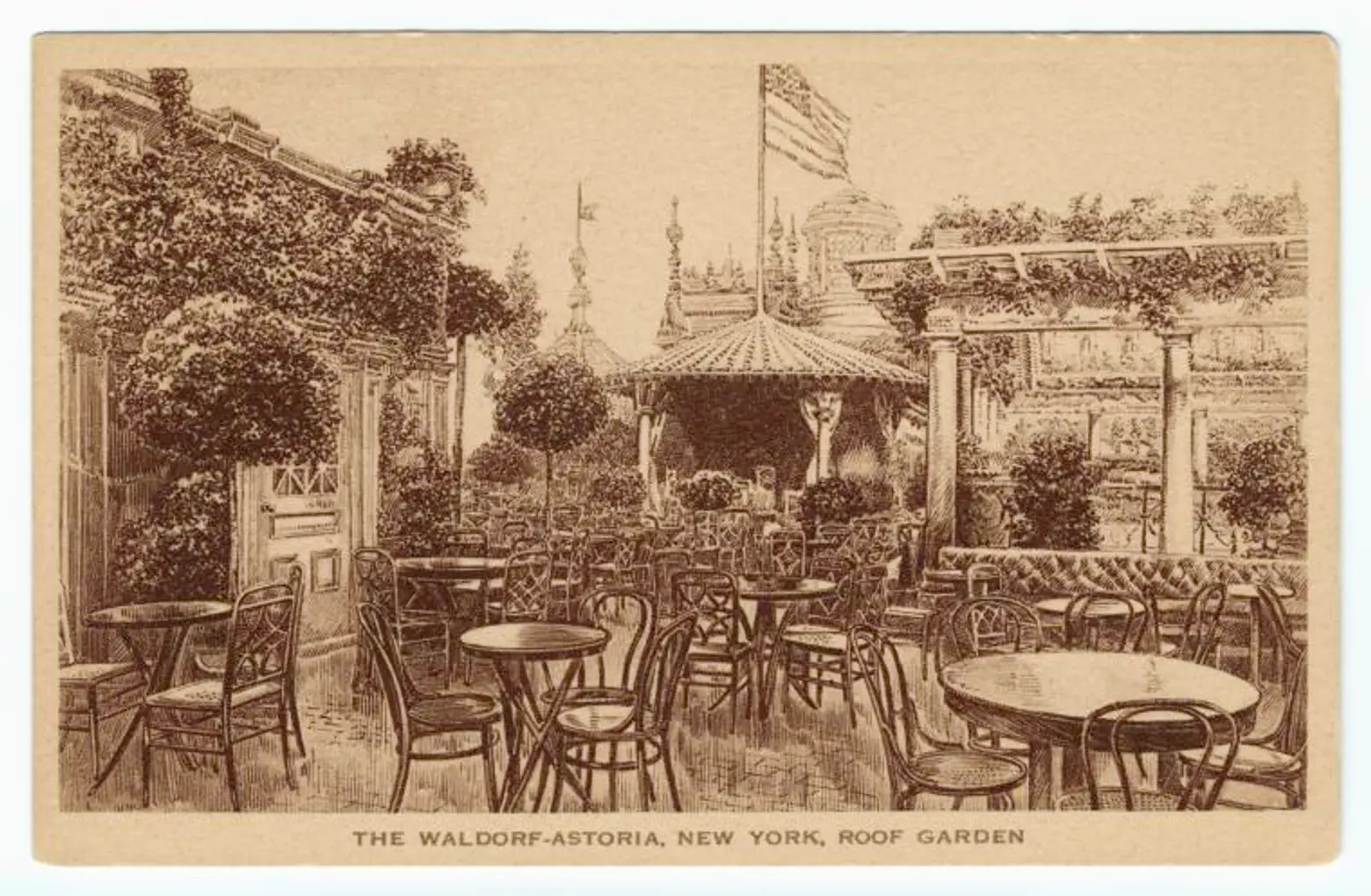

Waldorf-Astoria Roof Garden, 1908, via NYPL Digital Collections

The rooftop bar burst onto the scene in such a big way during the Gilded Age because the period’s then-cutting-edge technology made rooftops attractive to the urban middle classes for the first time ever. In a pre-elevator world, every building was a walkup. Accordingly, the lowest floors were the most attractive, the most expensive, and the most prestigious. Higher floors demanded the most tiring walks and commanded the lowest rents. In that context, the roof was the provenance of laundry, or the working class (the politics and poetry shouted from the rooftops and fire escapes of the Lower East Side in this period is the stuff of legend).

Then, suddenly, elevators made the penthouse the ultimate urban status symbol. Expansive views separated rich from poor in a new way. Now, the well-to-do could be “above” the poor not only in their own estimation but literally, higher up, above the urban masses.

But it wasn’t the ultra-wealthy hanging out at New York’s rooftop bars. Those with enough money to leave New York for the summer headed to Long Island or Newport. It was those with cash to spend, but not enough to get out of town, who sought the lofty libations on offer at New York’s roof gardens.

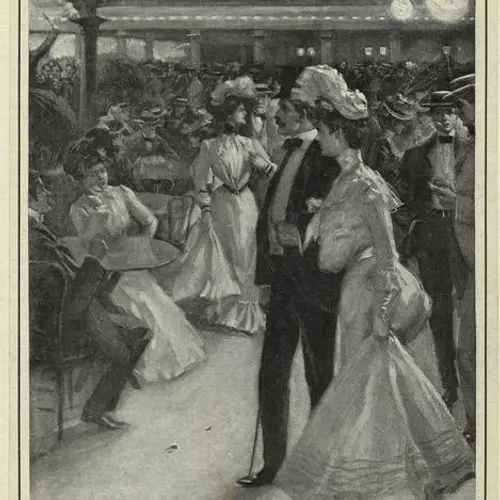

Of course, it wasn’t just the promise of booze, that sent New Yorkers flocking to early rooftop bars. Then as now, the seething city had one thing on its mind: The Daily Graphic observed in 1889, “There is a good deal of flirting going on in this ‘castle in the air,’ for the surroundings seem conducive to love-making.”

The original version of this story was published on 6sqft on May 20, 2019, and Archive on Parade on August 28, 2017.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.