The Durst Collection shows ‘New York Rising’ from the 17th century to the skyscraper age

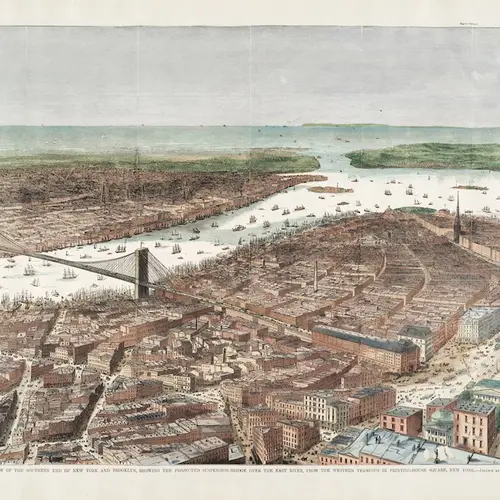

“Bird’s-eye View of the Southern End of New York and Brooklyn, Showing the Projected Suspension–bridge over the East River from the Western Terminus in Printing-House Square,” drawn by Theodore Russell Davis (1870)

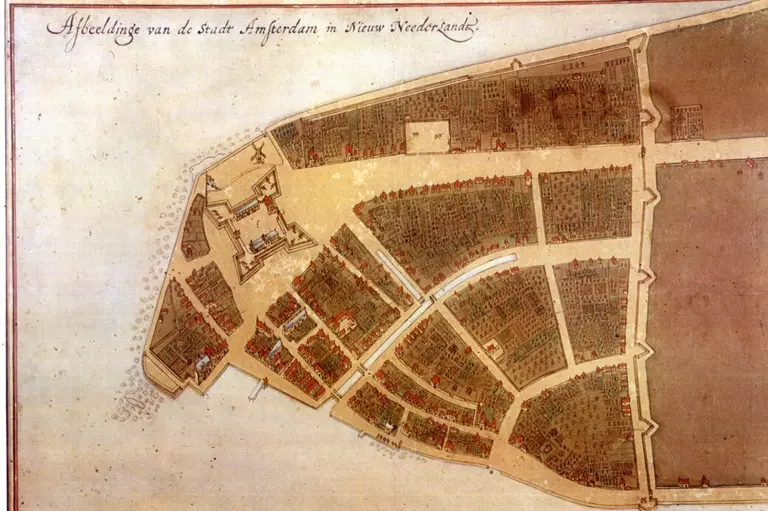

If you want to go on a visual journey that begins with Manhattan’s first European settlement, way back in the seventeenth century, up through the skyscrapers and urban planning of the late twentieth century, look no further than New York Rising: An Illustrated History from the Durst Collection. The book, set to come out on November 13th, originates from the sprawling Durst Collection at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library. Incredible photography captures the most definitive parts of New York history, accompanied by the thoughts of ten scholars who were asked to reflect on the images. Their writing ranges from the emergence of public transit to the “race for height” to affordable housing.

6sqft spoke with Thomas Mellins, who edited the book with Kate Ascher, on their efforts delving into the Durst Collection — which has its own unique history — to come up with this comprehensive visual history. See a selection of photos from the book, along with thoughts from Mellins, after the jump.

The former home of the Old York Library, the Upper East Side townhouse at 120 East 61st Street. Courtesy of Stribling

The former home of the Old York Library, the Upper East Side townhouse at 120 East 61st Street. Courtesy of Stribling

The Durst Collection comes from Seymour B. Durst, the patriarch of a New York real estate family that remains active to this day. He was a bibliophile and avid collector of New York memorabilia, fascinated by the city’s street grid, mass transit, ports, parks, and of course its monumental buildings and ever-evolving skyline.

Durst dubbed his collection the “Old York Library.” By the time of his death in 1995, his beloved library of nearly 35,000 books, maps, prints, postcards and other materials had taken over his entire five-story townhouse at 120 East 61st Street. Today, the collection lives at the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, known as the Seymour B. Durst Old York Library Collection.

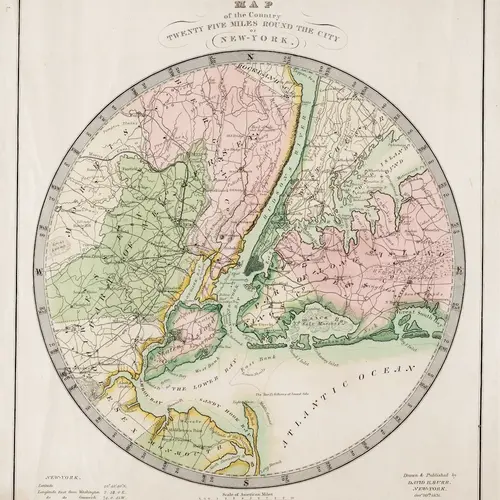

“Map of the country twenty-five miles round the city of New-York.” (David H. Burr, 1831)

“Map of the country twenty-five miles round the city of New-York.” (David H. Burr, 1831)

To categorize Durst’s sprawling collection of all things New York, Mellins and Ascher created ten categories: Laying the Groundwork (1640-1800), The Formative Years (1800-1860), The Rise of the Apartment (1860-1930), Moving the People (1880-1950), the Evolution of the Skyscraper (1890-1930), Housing the People (1930-1970), The Making of Midtown (1930-1980), Urban Renewal (1950-1980), Remaking Lower Manhattan (1960-1980), and Remaking Times Square (1980-2000).

“We were thinking of these collections almost like mini exhibitions of material on the different subjects,” Mellins says. Scholars were asked to contribute to each of the ten themes. “We wanted scholars to respond to the material in a personal way, and also use the imagry to tell a story they wanted to tell,” he says.

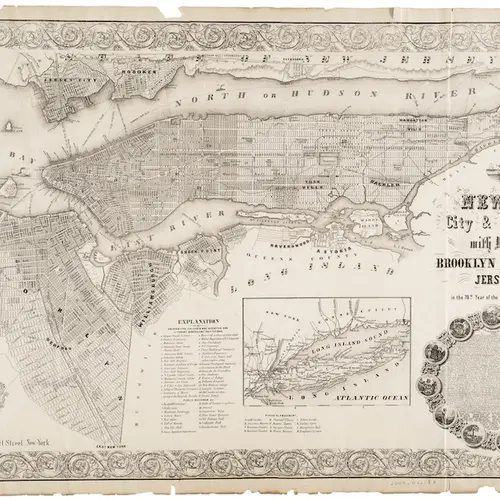

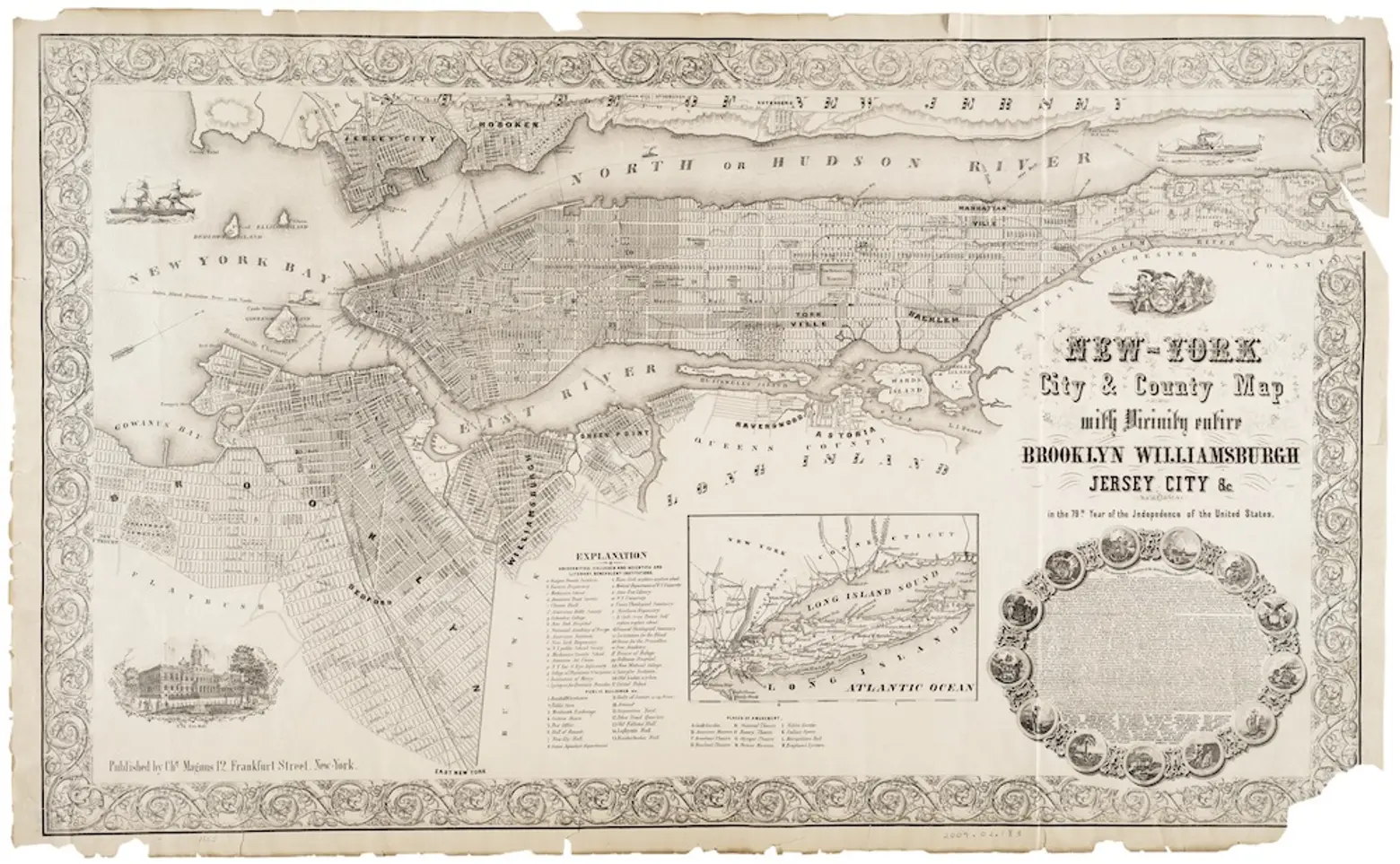

Photos courtesy of the Avery Collection. “New-York city & county map: with vicinity entire, Brooklyn, Williamsburgh, Jersey City & c. in the 79th year of the independence of the United States.” (Charles Magnus, roughly 1855)

Photos courtesy of the Avery Collection. “New-York city & county map: with vicinity entire, Brooklyn, Williamsburgh, Jersey City & c. in the 79th year of the independence of the United States.” (Charles Magnus, roughly 1855)

Maps are found throughout Durst’s collection, and therefore the book. There are a few unique selections, like an original 1811 Commissioner’s Plan map outlining the rectangular street grid that would determine the future development on Manhattan. An 1840 map of Broadway comes accompanied with an artist note: “Broadway is a noble street, and on its broad side-walks may be seen everything that walks the world in the shape of a foreigner, or a fashion — beauties by the score, and men of business by the thousand.”

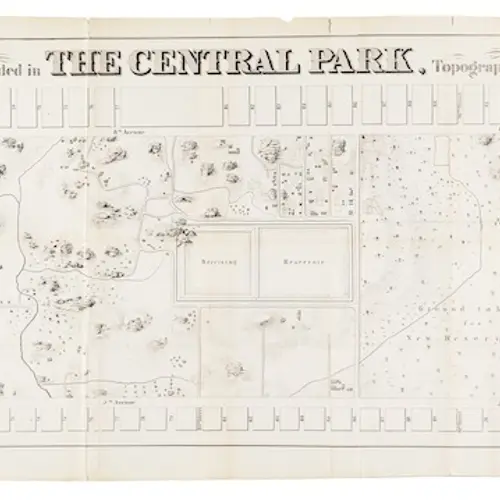

“Map of the lands included in the Central Park” (Egbert L. Viele, 1856)

“Map of the lands included in the Central Park” (Egbert L. Viele, 1856)

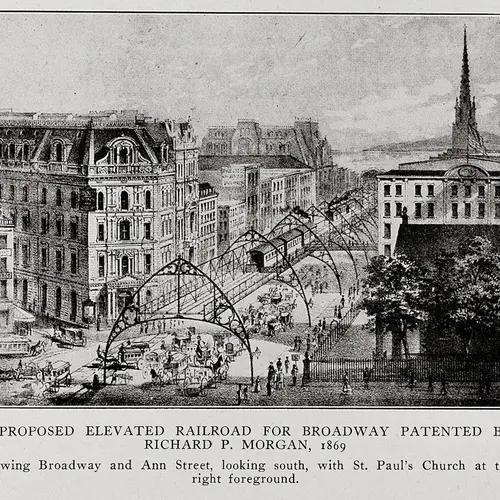

A Proposed Elevated Railroad for Broadway Patented by Richard P. Morgan, 1869. (William Fullerton, The First Elevated Railroads in Manhattan and the Bronx of the City of New York)

A Proposed Elevated Railroad for Broadway Patented by Richard P. Morgan, 1869. (William Fullerton, The First Elevated Railroads in Manhattan and the Bronx of the City of New York)

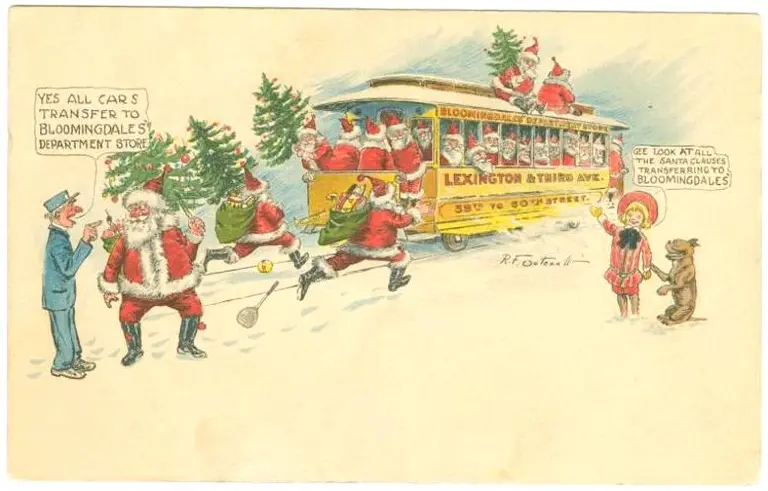

Mass transit is a reoccurring theme, as well. The book includes images of boats approaching Manhattan as a Dutch settlement, horse-drawn carriages on cobblestone streets, and the development of train lines and bridges.

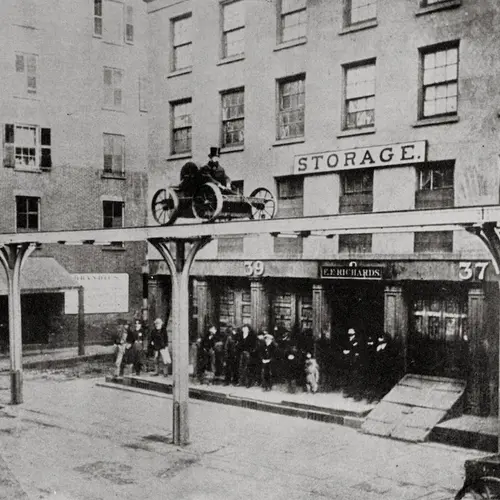

East Side of Greenwich Street, corner of Morris Street, December 1867. (William Fullerton, The First Elevated Railroads in Manhattan and the Bronx of the City of New York)

East Side of Greenwich Street, corner of Morris Street, December 1867. (William Fullerton, The First Elevated Railroads in Manhattan and the Bronx of the City of New York)

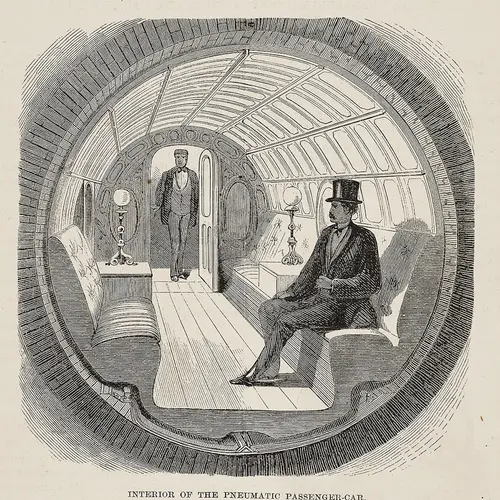

“Illustrated Description of the Broadway Pneumatic Underground Railway, with a Full Description of the Atmospheric Machinery, and the Great Tunneling Machine” (S.W. Green, 1870)

“Illustrated Description of the Broadway Pneumatic Underground Railway, with a Full Description of the Atmospheric Machinery, and the Great Tunneling Machine” (S.W. Green, 1870)

The book doesn’t just include images of built New York, as Mellins points out. The Durst collection offers plenty of images “of the city as it was never built,” he says. “It gives the collection another dimension.”

One example: the first NYC subway was build as a pneumatic tube, used to transport small packages and freight. (Luxury train cars were actually propelled by a vacuum under lower Broadway.) But the experiment was put to an end after the Panic of 1873, the financial crisis that triggered the Depression.

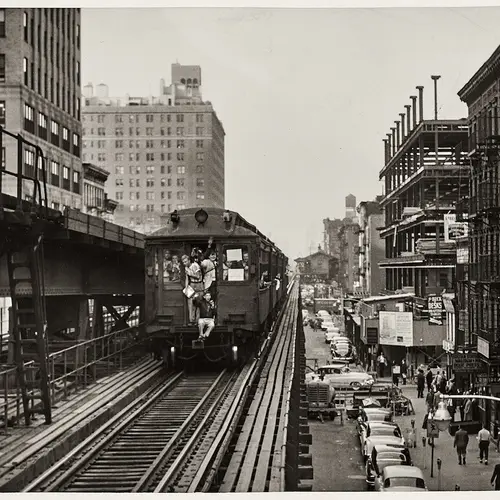

The last run of the Third Avenue El happened on May 12th, 1955. The destruction of Manhattan’s elevated lines happened in an orderly fashion between the mid-1930s and early 1950s. Because there was plenty of advanced notice, New Yorkers had a chance to ride their favorite lines one last time before demolition.

“Plan for the Rezoning of New York City; A Report Submitted to the City Planning Commission” (Harrison, Ballard & Allen, 1950)

“Plan for the Rezoning of New York City; A Report Submitted to the City Planning Commission” (Harrison, Ballard & Allen, 1950)

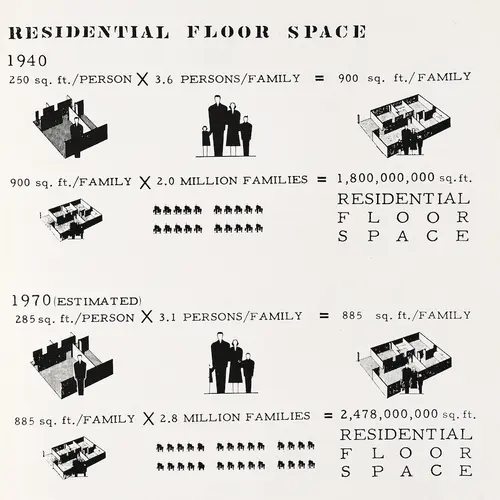

Two different scholars tackle housing: Andrew Dolkart writes in the section “The Rise of the Apartment,” while Hilary Sample writes on “Housing the People.” Dolkart writes on the emergence of tenement housing, middle-class apartment buildings, and luxury apartments, alongside images of elaborate floor plans. In “Housing the People,” which focuses on the years between 1930 and 1970, Sample discusses the role of NYCHA and Mitchell-Lama housing as urban renewal policies transformed Manhattan neighborhoods.

“The Park and City Hall,” (W. H. Bartlett, 1840s)

“The Park and City Hall,” (W. H. Bartlett, 1840s)

The obvious trajectory of New York Rising is the incredible growth of Manhattan over the years — from bridges and highways built, to parkland developed, to the birth of zoning and evolution of the skyscraper. Mells believes there are two messages of the book: “The growth of Manhattan told thematically and chronologically, and how you can use images and artifacts to understand history.”

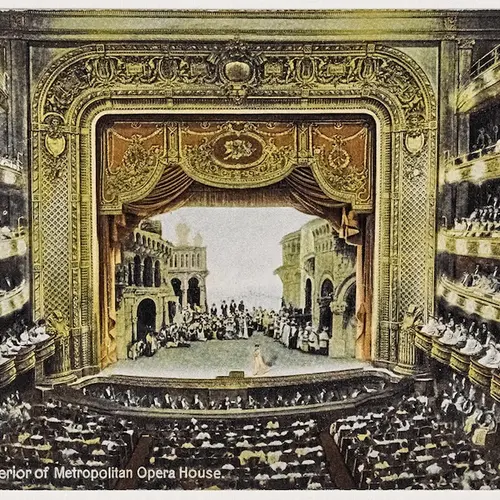

Interior of Metropolitan Opera House

Mellins can trace a link between the New York real estate world and this impressively comprehensive archive. “Historically, New York real estate has been more civically engaged than other communities,” he says. “In some ways, the fact that this collection was amassed by a New York developer is not completely surprising, simply because the community has been distinguished by its civic interest.”

But it isn’t just a real estate story. Though Mellins and Ascher focused on images that represent the development of Manhattan, Durst’s collection covers everything from women’s issues, public health matters, culture and entertainment. “It’s the vision of one man with a passion for his hometown,” Mellins says. “It’s both scholarly and really personal.”

RELATED: