New Yorker Spotlight: Paleontologist Mark Norell Spends His Days with Dinosaurs at the Museum of Natural History

Photo © AMNH

While the closest to dinosaurs most of us come is plastic toys and the occasional viewing of Jurassic Park, Mark Norell gets up close and personal with these prehistoric creatures on a daily basis, and it’s fair to say he has one of the most interesting jobs in New York.

As the division chair and curator-in-charge of the American Museum of Natural History’s Division of Paleontology and professor at Richard Gilder Graduate School, Mark’s work is very exciting. He studies not just dinosaurs, but a wide range of fossils from various time periods, and conducts research that benefits our understanding of both the prehistoric and modern world. And an extra perk of the job is surely his office–he occupies the entire top floor of the museum’s historic turret on the corner of 77th Street and Central Park West (we don’t recall Ross Geller getting an office like that!).

We recently spoke with Mark to learn more about paleontology and what it’s like to work at the museum.

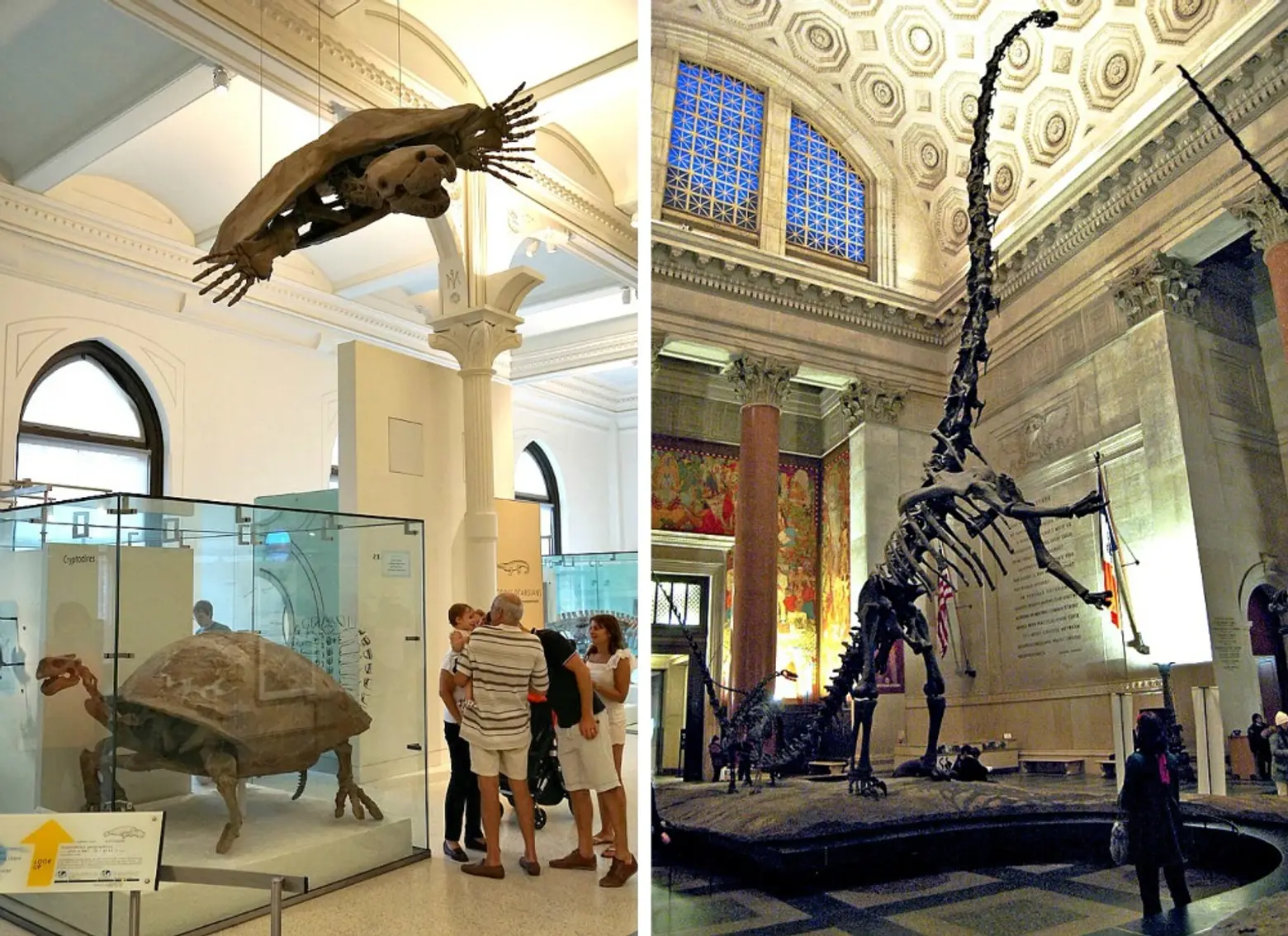

Fossils via Museum of NaturalHistory (12) via photopin (license)(L); Barosaurus via Wiki Commons (R)

Fossils via Museum of NaturalHistory (12) via photopin (license)(L); Barosaurus via Wiki Commons (R)

Growing up, did you love learning about dinosaurs and fossils

No; I was always interested in science, but I was never really into dinosaurs or anything like that. After I got my Ph.D., my first job was in molecular genetics. It wasn’t in paleontology. A paleontologist is someone who works with problems, and I’m more interested in addressing the problems than I am about necessarily finding everything there is to know about a certain dinosaur.

Most people hear paleontology and just think dinosaur bones, but it goes beyond that. What does a paleontologist do?

A paleontologist is someone who works on the remains of fossil organisms. It could be mammals, even bacteria. Most of us these days look at ourselves as biologists who work on fossils instead of living animals. I have worked on things as old as hundreds of millions of years to things that have only been dead for 4,000 years.

Mastodon in the fossil hall via Wiki Commons

Mastodon in the fossil hall via Wiki Commons

How does one become a paleontologist?

Mostly it’s biology. If you want to work at any kind of high level like a curator at a museum or a professor, it requires a Ph.D., and these days it requires post-doctoral training as well.

Can you share a bit about what your role at the museum involves?

I have a few different roles. First of all, it’s running and serving as a senior administrator in the Division of Paleontology. There are about 40 people total in our division, six of whom are curators, and then each one of us has technicians doing everything from preparing fossils to people who are illustrators to people who work in digital imaging like cat scanning and surface scanning.

Another thing I do is I supervise graduate students. The museum has a doctorate program with Columbia University, and I have a position at the school, so some of my students get their Ph.D.s there. The museum is also unique in having its own accredited graduate school, the Richard Gilder Graduate School. My other roles are research scientist, working on major institutional issues, working with development and education, and working on exhibitions. Additionally, we have 15-20 academic papers that come out of my lab. Some of them have broad appeal in the sense that they make it onto the cover of the Times or USA TODAY. We always have stuff going on and we are always trying to figure out what the next thing will be.

The Gobi Desert via Wiki Commons

You conduct a great deal of theoretical research. What areas are you currently researching?

We have so many different projects that we are working on right now. A large one is looking at the evolution of brains within birds and the dinosaurs to which they are most closely related. We do everything including taking cat scans of many different living birds, fossil birds, and fossil dinosaurs. Then we create virtual brains in our computers and mathematically describe those to compare things like sizes and shapes and a whole class function.

We also have a lot of field projects. For the last 25 years we have been excavating in the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. We’re also excavating in a couple of places in China and in the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. I’m gone about a third of the time. I usually spend about a month or so excavating in Mongolia each summer and a few weeks in the Carpathian Mountains. I also travel back and forth to China a couple of times a year.

What is it like to work in the field?

It’s different in every place. The most hardcore location is the Gobi Desert. When we go out into the desert to our base camp, there’s only a road for a few hundred kilometers and it takes a few days to get there. We have to have all of our food, gasoline, and everything we might possibly need for the time that we stay there. Conditions can be pretty hard. It’s very cold at night, but can be 120 degrees during the daytime. We don’t have a lot of water so you can only bathe so often.

When we excavate in Romania it’s the opposite. The places we excavate are either in rivers, riverbanks, or on the sides of cliffs, and the rest of the area is covered in forests. The evenings we stay at the guesthouse, and there is great food. It’s kind of like going to summer camp. In China, it depends on where you are. If you’re in the northeast or southeast, generally you will stay in very modest hotels. In the far west, we actually camp out.

Fossil Hall © AMNH

Fossil Hall © AMNH

How are the museum’s fossil halls laid out?

When I arrived at the museum it was a period of big changes. It was the first time they brought on a paid president. Part of the reorganization that happened was that the board decided we should redo the fossil halls on the fourth floor since they’re one of the iconic halls of the museum. We put together a team and hired Ralph Appelbaum as the designer, and then we, the curators, sat down and came up with a theme to show the fossil halls off. Up until this point, things were arranged chronologically, but we decided to go with a much more ambitious kind of thing, which was basically to walk through the tree of life with fossils branching off. They’re arranged so they are near their closest relatives as opposed to time periods. It will be 20 years ago next year that the theme was put in place, and it’s been incredibly successful. The halls are visited by 4-5 million people a year and continue to be the most popular in the museum.

What is one thing most New Yorkers don’t know about fossils?

I think one thing they don’t know is that the first dinosaur was found in North America, about 13 miles south of here in New Jersey.

Tyrannosaurus Rex via Dinosaur via photopin (license)

Tyrannosaurus Rex via Dinosaur via photopin (license)

Is there a hidden “secret” of the fossil halls you can share with us?

I think one of the neat things is if you look at the ribs of the Tyrannosaurus Rex, you can see that they are all broken at one point and then they heal. They have knobs in the middle of them. It was probably a mean animal to begin with, and if you can imagine an animal of that size with painfully broken ribs, it’s pretty amazing.

In addition to the fossil halls, what other exhibits have you worked on?

I’ve curated exhibits at the museum, which have included the World’s Largest Dinosaur; Dinosaurs: Ancient Fossils, New Discoveries; Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs; and Traveling the Silk Road. I was also co-curator for Our Global Kitchen: Food, Nature, Culture and Mythic Creatures.

What does conducting research in this field and being able to share it through the museum mean to you?

People who work on dinosaurs always talk about how dinosaurs are kind of like this entry point for science. When you talk about things like thermodynamics, earth history and evolution, geology, and things that people might not be interested in, you can use dinosaurs as a tool to be able to talk about these topics. It’s not that I’m really that interested in dinosaurs, I’m just really interested in asking questions and then figuring out if we are clever enough to answer them.

***

[This interview has been edited]

American Museum of Natural History

Central Park West at 79th Street

New York, NY 10024

RELATED: