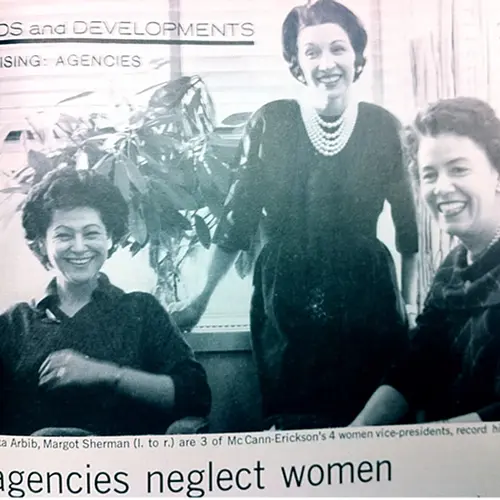

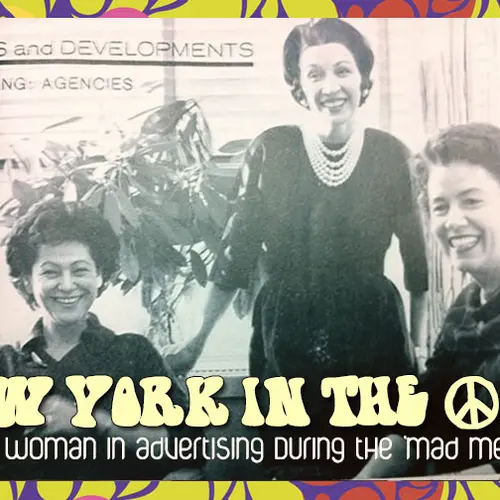

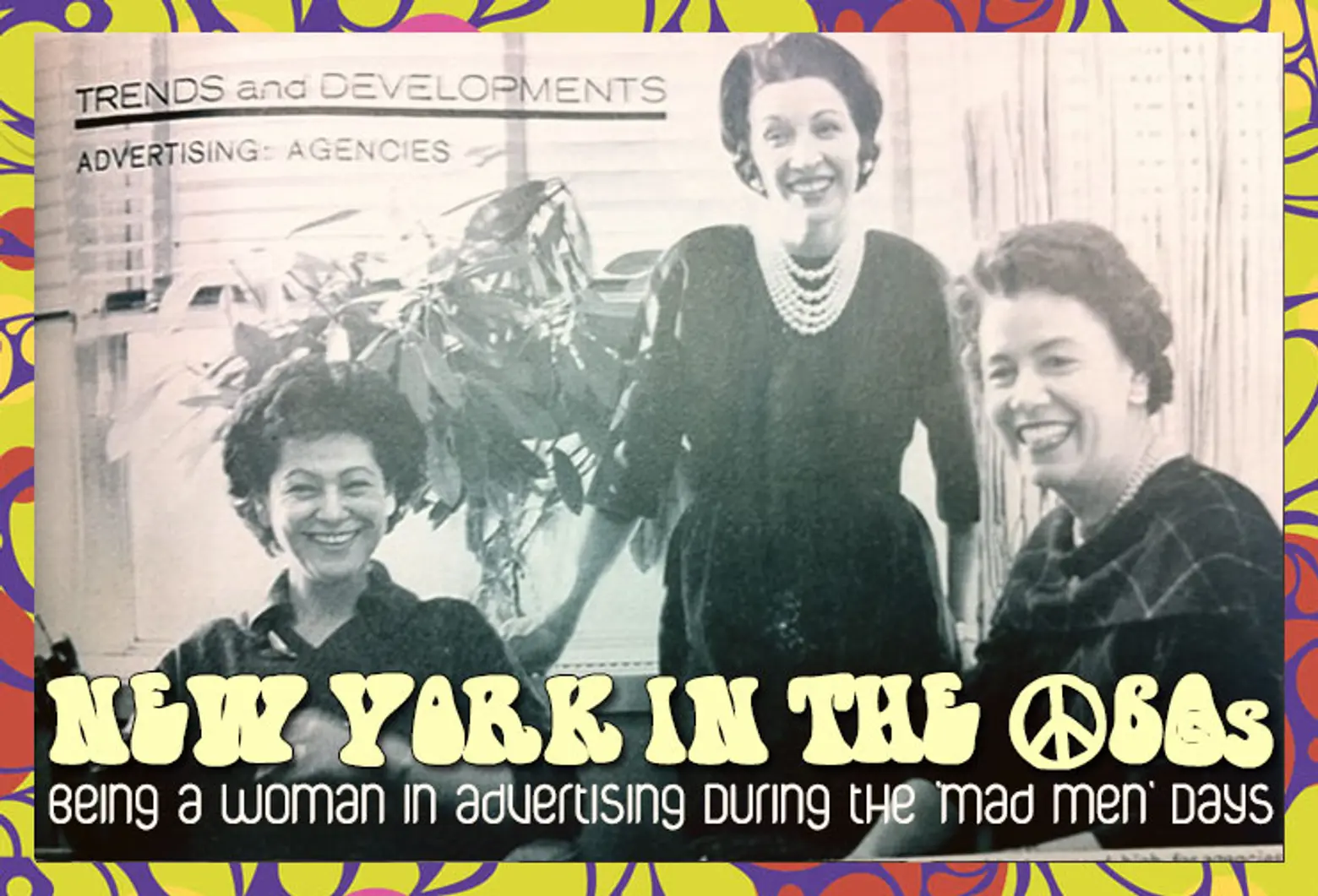

New York in the ’60s: Being a Woman in Advertising During the ‘Mad Men’ Days

Our series “New York in the ’60s” is a memoir by a longtime New Yorker who moved to the city after college in 1960. Each installment will take us through her journey during a pivotal decade. From $90/month apartments to working in the real “Mad Men” world, we’ll explore the city through the eyes of a spunky, driven female. In our first installment, we went house hunting with the girl on the Upper East Side, and in the second, we visited her first apartment and met her bartender boyfriend. Now, we hear about her career at an advertising magazine… looking in on the Donald Drapers of the time.

+++

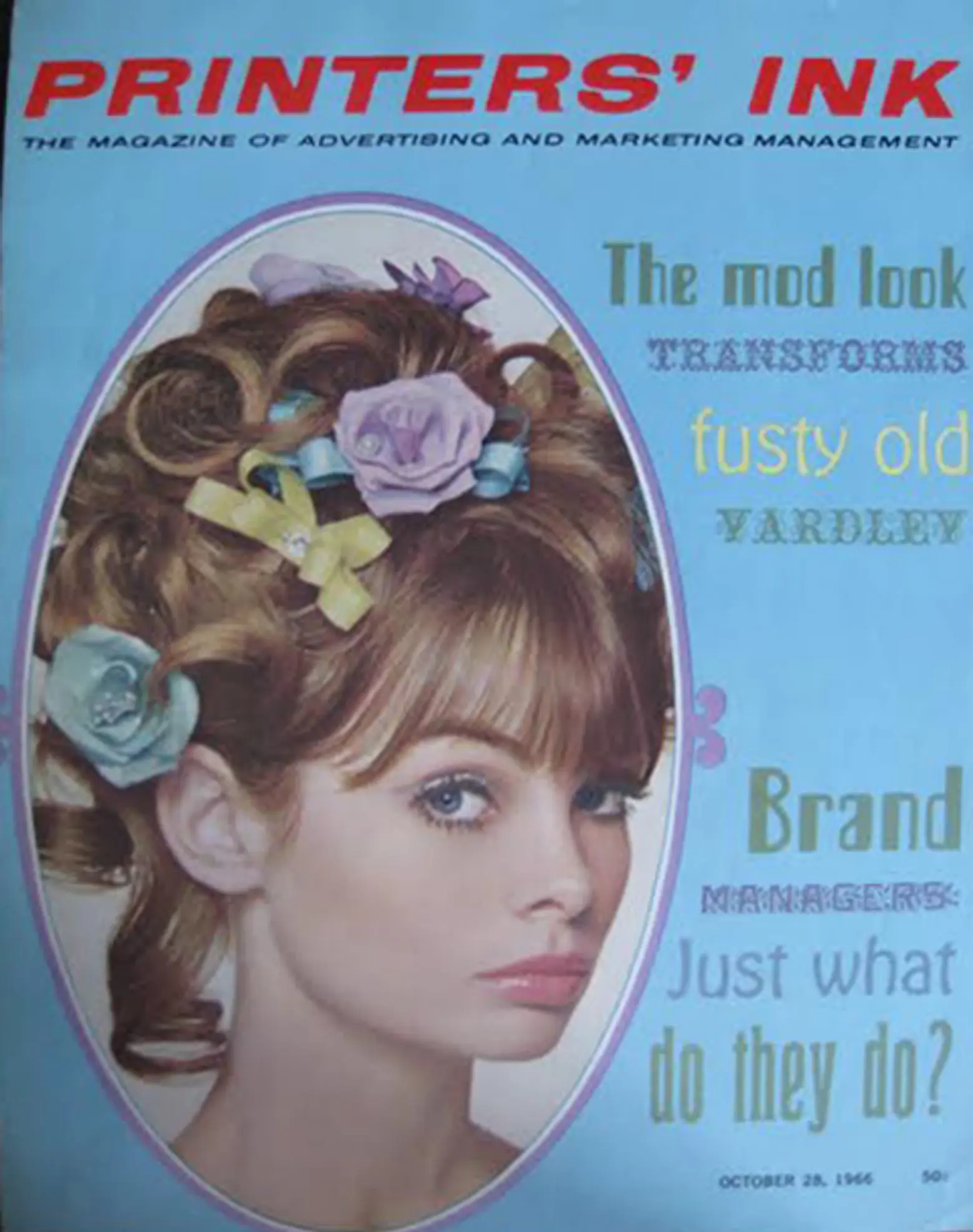

Having been led to expect jobs commensurate with the prestige of her Eastern women’s college, the girl gradually came down to earth and accepted a job at Printers’ Ink magazine, a publication serving the advertising and marketing industry. Her job was to open and sort mail, answer the phone and type manuscripts. She was, however, told that the possibility existed for her to become an editor there, and that’s why she took it. It paid $90 a week. At least she didn’t have to empty ashtrays.

Everyone had his or her own typewriter and turned out stories on paper with a column in the middle that corresponded in character count with the width of a printed column. Sometimes the editing on the manuscript made the story hard to read, so it needed to be retyped. The art department would take the corrected manuscript and use rubber cement to paste art work, headlines and subheads where needed and send the completed layouts to the printer for page proofs. The girl began to hang out in the art department when she had free time.

The writers and editors there were impressive. They were smart and well connected, clever and funny. One of them had been on staff at the New Yorker, another was a stringer for the Economist. The executive editor had been on the Army’s famed publication Stars and Stripes, was a member of the Overseas Press Club and edited a couple of books about wartime journalism. One of the stand-out writers was Allen Dodd, who used to say there were only two ways to write: point with pride or view with alarm. He wrote a brilliant piece for PI called “The Job Hunter,” and it resonated so much he later developed it into a successful book of the same name. His ghost can still be heard asking a colleague, as they approached the 7th floor elevators on the way to a press conference, “Well, do you think we have time to take a taxi?”

The women were well connected too, but more especially they were well dressed, in clothes the girl now wonders how they could afford—one wore a gorgeous emerald green wool suit with a silk blouse. The men wore suits to the office too, taking the jackets off to work. Winter and summer, even on 90-degree days, the men put on their jackets to go out of the building. And every morning, despite the season, the women struggled into girdles and stockings and left home in heels.

The office was on Madison Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets, in a building that is still there. The girl took the 79th Street bus crosstown and the Madison Avenue bus downtown, since the avenues were mostly two-way in those days. She used to look out the window at the fine Madison Avenue buildings she passed and especially liked the Bank of New York, a colonial at 63rd Street that looked more like a house than a bank. Free-standing houses like that one were practically non-existent in Manhattan.

Madison Avenue hasn’t changed much in 50 years. Of course, many of the shops have changed, and now more French couturiers’ ready-to-wear shops are there; but the architecture and ambience are much the same. Some advertising agencies had their offices there; just as many had theirs on Third Avenue or Lexington. The fabled Jim’s Shoe Repair was on 59th Street between Madison and Park, and the girl took all her shoe problems there. The French Institute, Alliance Française, was and is on 60th Street between Madison and Park. The girl took French there at a 6:30 evening class. She used to leave work at 5:15 or so, walk to the Hotel Delmonico (now Trump Park Avenue) at the northwest corner of Park and 59th Street, sit at the bar or a small table, order a beer, eat peanuts and potato chips and study French until, fortified, she had to leave for class.

On her lunch hour, the girl would often go to Bloomingdale’s or stroll down to Design Research on 57th Street and spend as little as possible on clever things, one or two of which she still has. Sometimes she would go down Lexington Avenue to Azuma and buy useful, attractive things she no longer has. It was a nice way to spend an hour’s break.

Sometimes she would go to the corner and order a hot pastrami with mustard on half a hero from Rudy. He was the first black person she knew and he made the best sandwiches. He plucked a baguette, chopped it in two with one stroke of a carving knife, sliced it open with another, and slathered the bread with mustard. Then, turning to reach behind him, he removed the lid of a hot bath with one hand and with tongs in the other, lifted out slices of hot pastrami, dropped them onto the bottom half of the hero, arranged them a little, popped the top half of the hero on, sliced the half in half again and, slipping the knife under the sandwich like a spatula, raised lunch onto white deli paper, folded the ends around it, put it in a bag and smiled as he handed it to the girl, all in about the same amount of time it takes to read this. She loved to watch it. She loved the sandwich, too.

One of the cover stories the girl wrote for Printers’ Ink. It was picked up by The Times of London, read there by by local financial interests who arranged a stock transfer with Yardley.

After more than a year and half of typing manuscripts and sorting mail, one day the girl sat down in the executive editor’s office and held him to his word. He stubbed out his cigarette and said, “All right, you can review business films.” The magazine didn’t normally run business-film reviews, but he said they could start. She wrote one. They liked it and ran it. She wrote another, and they ran that one too.

Then she was appointed to assistant editor and given a cubicle and a beat, what reporters call a field of assignment. It was not the beat she wanted; she wanted the one covered by the woman in the emerald green suit, and after another couple of years and another couple of people were promoted, she had it.

Early on, she had a business lunch. She was to meet two or three men at a nearby restaurant and get a story from them over lunch. They ordered martinis to go with their cigarettes, so she did as well, in order not to seem rude or worse, prissy. The martinis should not have come as a surprise. These were advertising people. Advertising people were famous for three-martini lunches. Maybe they didn’t drink as much as “Mad Men” would have you believe, but they drank enthusiastically.

One who didn’t seem to suffer afternoon doldrums from this custom was the managing editor. He would return late from a liquid lunch and bang out an editorial with two fingers faster than most people can do it with ten. They were good editorials, too.

+++

RELATED: