New York in the ’60s: Women in the Workplace and the Changing Face of Print Media

Image via wackystuff/Flickr

“New York in the ’60s” is a memoir series by a longtime New Yorker who moved to the city after college in 1960. From $90/month apartments to working in the real “Mad Men” world, each installment explores the city through the eyes of a spunky, driven female.

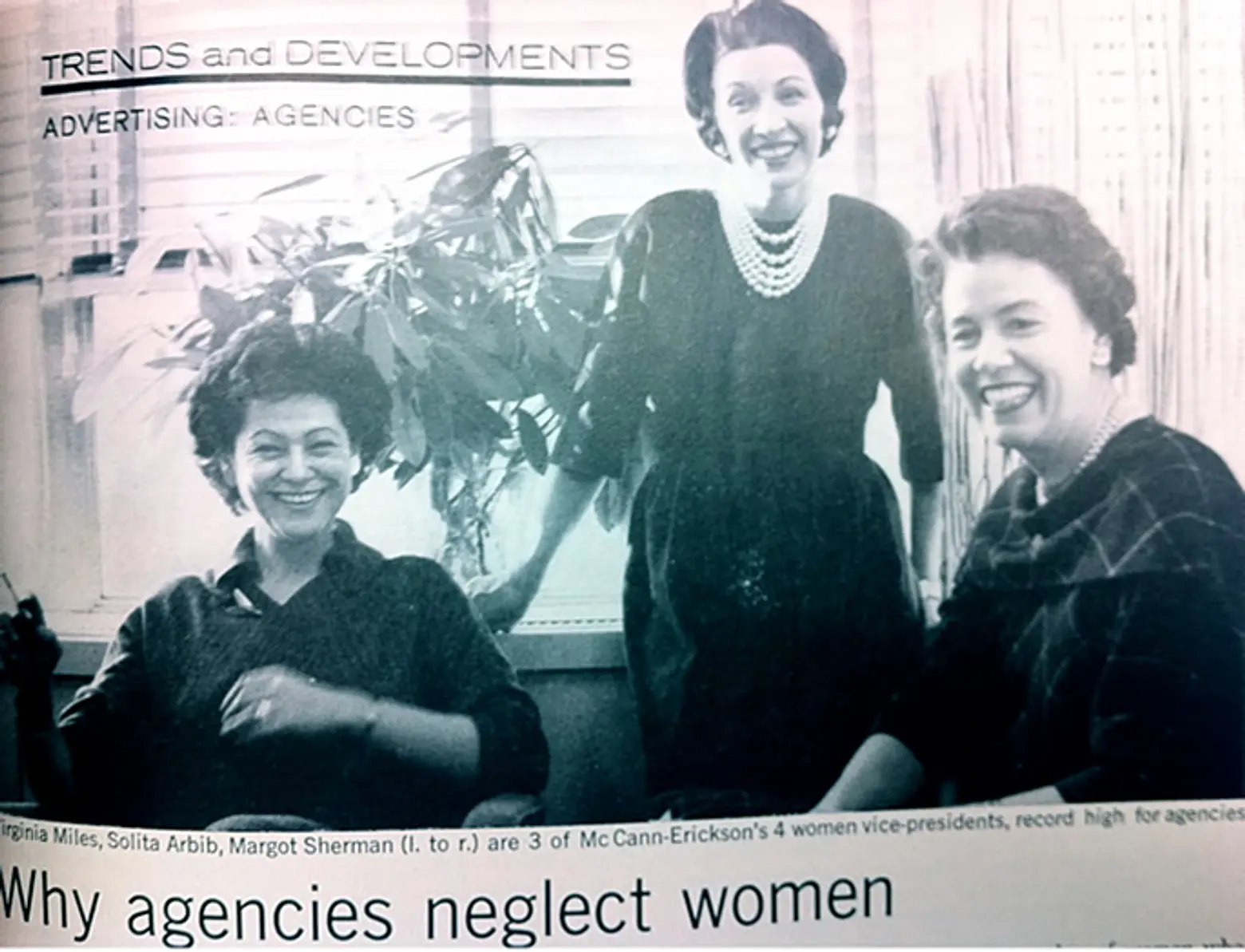

In the first two pieces we saw how different and similar house hunting was 50 years ago and visited her first apartment on the Upper East Side. Then, we learned about her career at an advertising magazine and accompanied her to Fire Island in the summer. Our character next decided to make the big move downtown, but it wasn’t quite what she expected. She then took us through how the media world reacted to JFK’s assassination, as well as the rise and fall of the tobacco industry, and now she sheds some light into how women were treated in the workplace at this time.

One day when the girl was a senior editor, a new man was hired. He was brought in from another business magazine as an associate editor covering one of her former beats. They got to know each other a little; it turned out that he was younger than she was, also unmarried, less experienced as a writer/reporter and not knowledgeable about the advertising and marketing field. Also lower ranking on the masthead. His salary was $8,000 a year. The girl’s was $6,000.

She marched into the editor’s office and demanded to know why someone less experienced, less well grounded in the field, younger and maybe not as good was being paid one-third more than she was. “Why am I not being paid what he is being paid?” she wanted to know.

“You might get married.”

“And I might not. He is not married and does not have a family.”

“But he has to take girls out.”

“Whereas I can’t afford to go dutch. Besides, you should be paying for the work, not for how you imagine people might spend their money.”

This went on a bit longer. More details are lost in the miasma of memory, but one should note at this point that there were no benefits for paid staff—no health care, no bonuses, no pensions, no nothing. Interestingly, the discussion the girl had with the editor about pay did not touch on benefits at all. They were rare in those days.

Although the girl’s truncated salary could hardly have affected the corporation’s bottom line, it must be said that Printers’ Ink had been losing money for some time. A magazine that came out every two weeks suffered a disadvantage against one, such as Advertising Age, that came out every Monday with more up-to-date news. Eventually the losses became so dire that the publisher decided to terminate two thirds of the staff, change the magazine’s name and move offices. The girl was one of those lopped off.

First, a shot at her dream job, Newsweek. She made an appointment with Jack Kroll, who was the editor of the back of the book, and when she told him what she wanted to do—she had five years of writing under her belt by now—he said, “We don’t hire women to write.”

“Why not?”

“Because they’re hysterical. Although from the look of it, I don’t think you would be.”

The time was ripe to free-lance. Print media in general was undergoing a contraction. There had been a ruinous newspaper strike that lasted nearly four months in 1962-63, basically about automation and the jobs that would be lost because of it. One of the upshots of that strike had been to combine some papers and beef up others. The New York Herald Tribune, for instance, itself the offspring of the NY Herald and the NY Tribune in 1924, put more effort into its business coverage and merged ever so briefly with the New York World Telegram and the New York Journal American to become the New York World Journal Tribune. More effectively, it hired Clay Felker, an alumnus of Time-Life and an editor from Esquire to run a new Sunday magazine to be called “New York,” the forerunner of the present New York magazine, which was born when the Herald Tribune itself died in 1966.

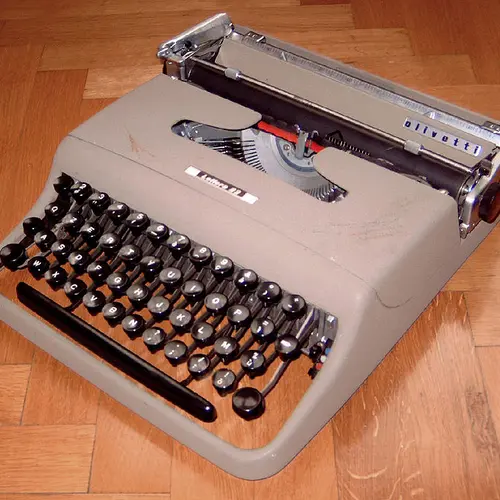

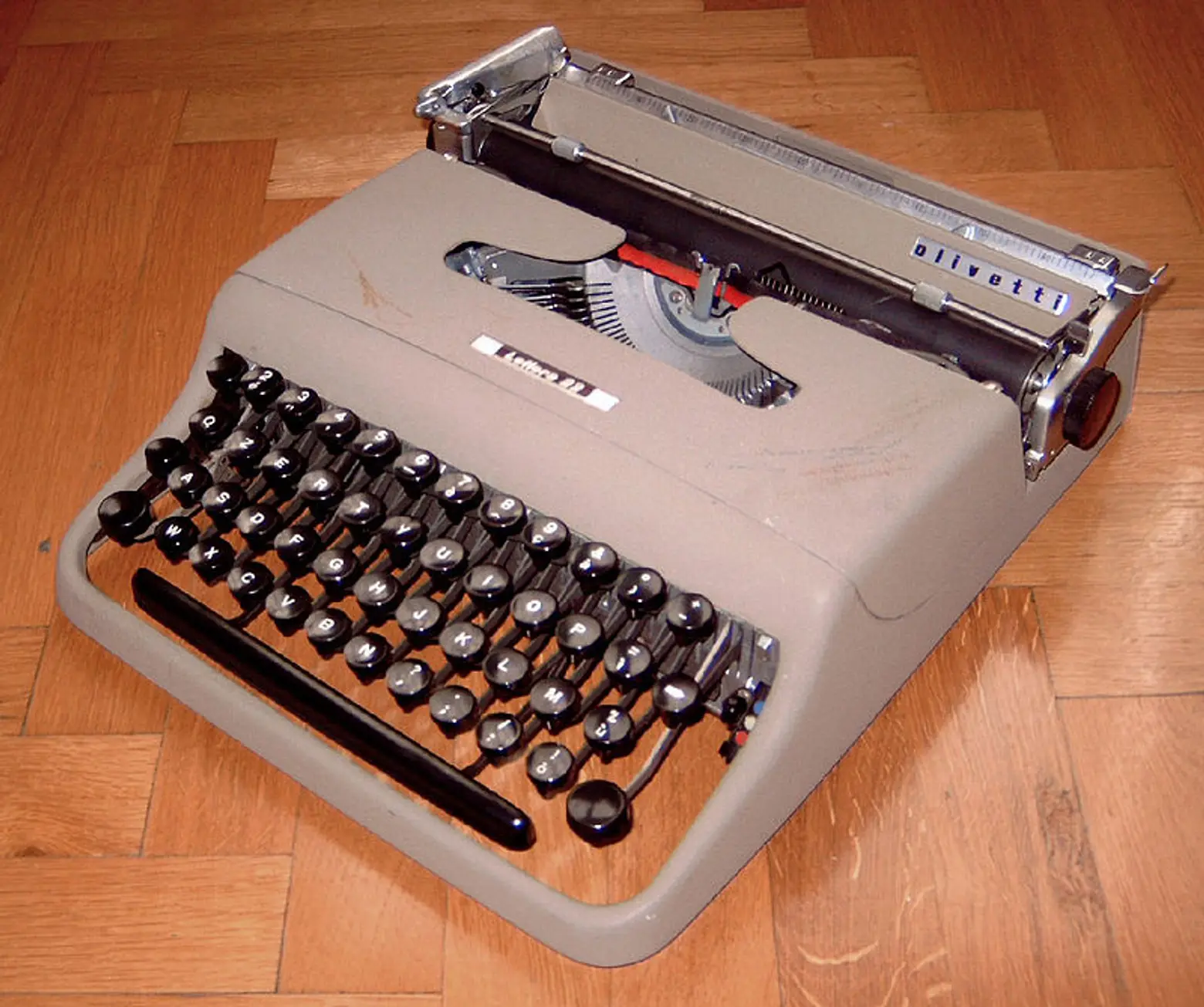

Olivetti Lettera 22 portable typewriter

The girl called up all the contacts she had made and through them, went to see Clay Felker. He gave her—a fledgling—an assignment. He gave her another and another. He set her up with Gloria Steinem, who had been a colleague of his at Life magazine, and the two met for coffee and discussed story ideas. The girl offered a limp one about cockroaches and received “they’re certainly a common denominator,” but not an assignment.

Other contacts did result in assignments. A regular gig was Bride & Home magazine, where she learned how callously models are reviewed and dismissed, forever killing any desire the girl ever had to be one, even if she had had the physical attributes—what girl doesn’t dream of becoming a model? She wrote numerous articles, one of them advising readers what they should expect to pay to furnish their first homes. For a bed, expect to pay $160 to $340; for a headboard $60-125; $250-600 for a sofa, and $190-400 for a refrigerator. The only appliance that doesn’t seem to have escalated dramatically in cost was an air-conditioner, estimated in 1965 at $125 to $250.

Another telling assignment was for Mademoiselle on career opportunities for girls in computer programming, published in January, 1967. It said that an estimated 180,000 people worked in computer programming and related work in 1966 and that most of them were men, “but that’s a reflection of greater interest among men rather than a company’s reluctance to hire a girl. What discrimination there is usually is practiced on payday…” The article cited instances where women earned $10,000 to $15,000 a year, handsome remuneration, clearly on a par with men’s.

At the end of the year, the girl added up what she had made cranking out stories on her Olivetti Lettera 22 portable typewriter and it came to $8,000—one third more than she had made on staff. So there, Printers’ Ink!

+++

RELATED:

- New York in the ’60s: Apartment Hunting, Job Searching, and Starting Out in the Big City

- New York in the ’60s: Domestic Yearnings, Yorkville Hangouts and Bartenders

- New York in the ’60s: Being a Woman in Advertising During the ‘Mad Men’ Days

- New York in the ’60s: Beach Parties and Summer Houses on Fire Island

- New York in the ’60s: Moving Downtown Comes With Colorful Characters and Sex Parties

- New York in the ’60s: When Chelsea Apartments Were $111 a Month

- New York in the ’60s: The Assassination of JFK and the Plight of the Tobacco Industry