Lillian Wald’s Lower East Side: From the Visiting Nurse Service to the Henry Street Settlement

Henry Street Nurses, courtesy of The Henry Street Settlement

In 1893, the 26-year-old nurse Lillian Wald founded the Lower East Side’s Henry Street Settlement, and what would become the Visiting Nurse Service of New York. Two years of nursing school had given her the “inspiration to be of use some way or somehow,” and she identified “four branches of usefulness” where she could be of service. Those four branches, “visiting nursing, social work, country work and civic work,” helped guide the Settlement’s programming, and turned Wald’s home at 265 Henry Street into a center of progressive advocacy, and community support, that attracted neighbors from around the corner, and reformers from around the world.

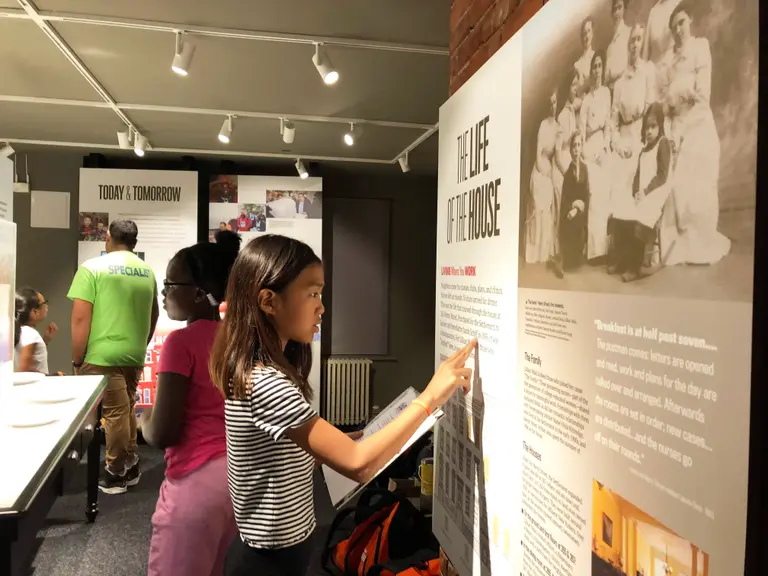

This year, The Henry Street Settlement is celebrating its 125th anniversary. To mark the milestone, the house on Henry Street has unveiled an interactive, multi-media exhibition detailing the history of the Settlement, and exploring the life and legacy of Lillian Wald.

Though Wald lived and worked on Henry Street for more than 30 years, her life began far from the bustling Lower East Side. She was raised in an upper-middle-class German-Jewish family in Rochester, New York, but moved to New York City in 1889 to study nursing, one of the few professional careers then open to women.

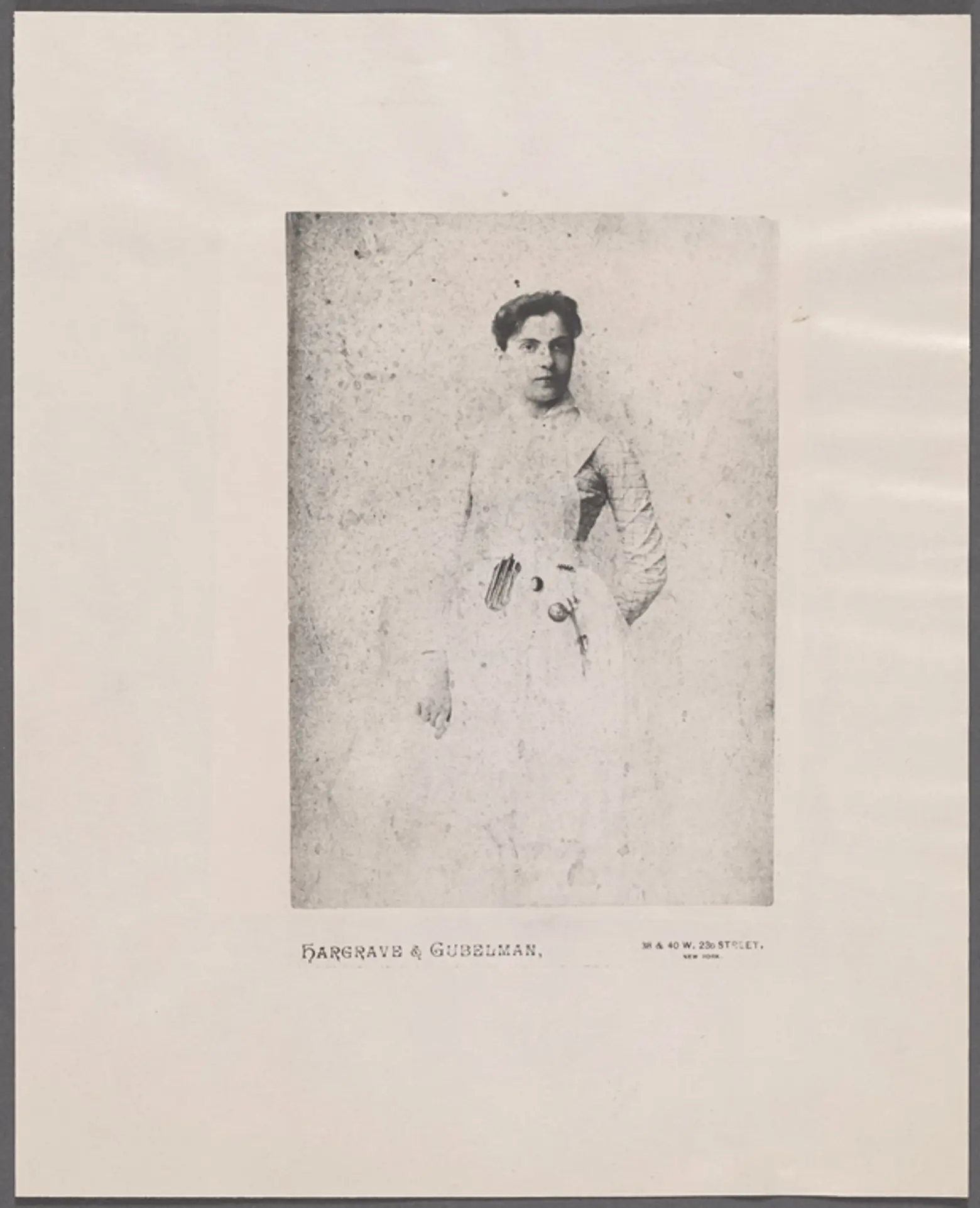

Lillian Wald, upon her graduation from nursing school, via NYPL

Lillian Wald, upon her graduation from nursing school, via NYPL

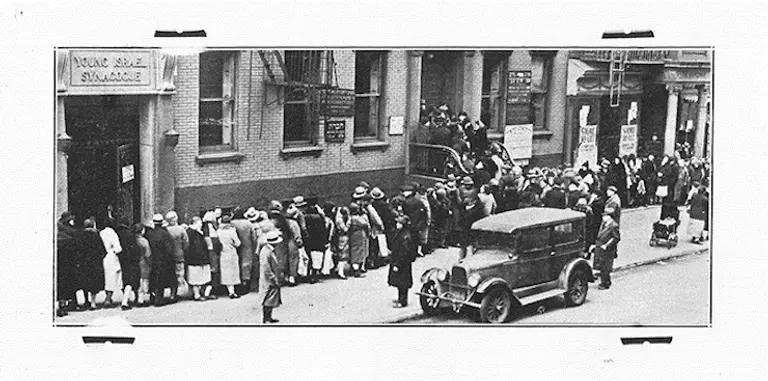

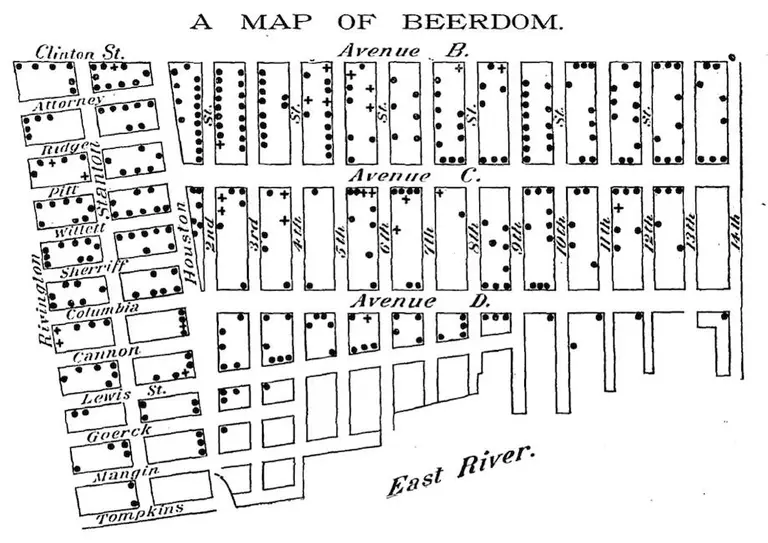

Wald was not the only new arrival in New York at that time. Between 1880 and 1920 more than 19 million immigrants would make their way to America, and most would settle in New York. So many people made their new homes on the Lower East Side that the neighborhood became the most densely populated place in the world. These newest New Yorkers faced poverty as low-paid sweatshop laborers and the threat of disease in squalid, over-crowded tenements.

Wald became aware of the challenges of life on the Lower East Side while teaching a class on nursing in the neighborhood in March 1893. A little girl entered the classroom crying out for help; her mother was dying at home on Ludlow Street. Following the little girl to her mother’s bedside, Wald saw that the young mother had hemorrhaged while in labor, but had been abandoned by her doctor, due to her inability to pay his fee.

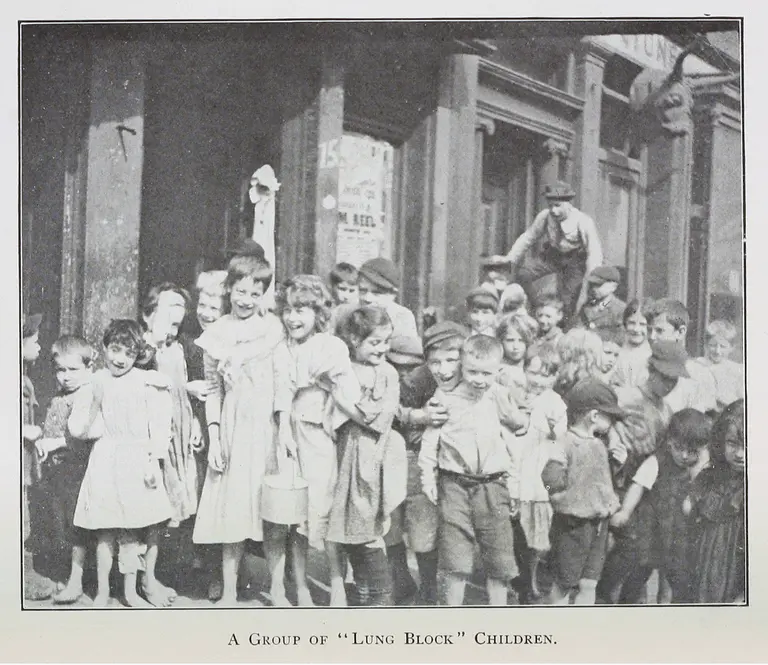

Wald called the experience her “Baptism of Fire.” She was ashamed to live “in a society that permitted such conditions to exist.” It was a society without workers’ compensation or sick leave, where police stations served as the city’s only homeless shelters, where children played in the streets for want of playgrounds, and lack of access to clean milk or water made the infant mortality rate 1 in 10.

Conventional wisdom at the time looked at the inhumane conditions caused by unfettered industrialization with indifference, or smug condemnation: Conservatives believed the poor were poor due to their own moral failings. But, social reformers believed that society had failed the poor by failing to address the social conditions that impoverished them.

As a nurse, Wald understood that when she encountered a sick patient, she was dealing not only with an illness but also with the conditions that caused it. She wrote, for example, that tuberculosis was “pre-eminently a disease of poverty, and can never be successfully combatted without dealing with its underlying economic causes: bad housing, bad workshops, undernourishment and so on.”

Wald believed that a democratic government must help alleviate poverty, and understood that social justice work was democracy in action: she maintained that working as a nurse on the Lower East Side was a way for her to “assert by deed [her] faith in democracy.”

Wald and Brewster in their first Lower East Side Apartment, on Jefferson Street, courtesy of the Henry Street Settlement

In order to begin that active service, she and her fellow nurse Mary Brewster decided to move to the Lower East Side. Wald wrote that the two women would, “live in the neighborhood as nurses, identify ourselves with it socially, and, in brief, contribute to it our citizenship.” Wald and Brewster began their lives on the Lower East Side living at the College Settlement on Rivington Street, which had been founded in 1889 by a group of seven graduates from the nation’s women’s colleges.

The Settlement Movement was a new social reform movement then flourishing around the country, and on the Lower East Side in particular. It was led primarily by college-educated, well-to-do women like Wald who lived, or “settled,” amongst the working poor to offer social services, build community spaces, and fight for social change.

Critics of the movement, and many residents on the Lower East Side, saw settlement workers as self-righteous do-gooders, separated entirely by wealth and personal experience from the people they claimed to want to help. In January 1910, The Hebrew Standard Newspaper reported that settlement workers were a “horde of professional ‘uplifters’ whose highest ambition, as a rule, is to prate and write glibly about the ‘ghetto people’… the sooner we get rid of them, the better.”

When Wald arrived on the Lower East Side, she knew that she and Brewster had a lot to learn. After three months at the College Settlement, they moved to an apartment on Jefferson Street. Wald noted, “the mere fact of living in a tenement brought undreamed-of opportunities for widening our knowledge and extending our human relationships.”

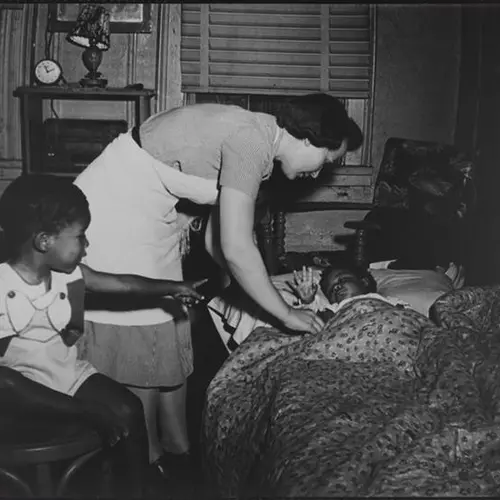

Wald’s commitment to forging deep relationships with her neighbors and her neighborhood distinguished her work from traditional settlement work. When she created the visiting nurse service in 1893, she noted that treating patients in their own homes and revisiting patients regularly in “intimate and long-sustained association, not only with the individual, but with the entire family, gives opportunities that would never open up if the acquaintance were casual, or the settlement formally institutional.”

In a very real way, Wald saw her neighbors as members of her family. “She told us [that] all of us…were members of one large family, with common interests, common problems, and common responsibilities,” remembered Abraham Davis, who had been part of a boys club at the Henry Street Settlement at the turn of the 20th century.

For Wald, that also meant welcoming her neighbors into her home for dinner and hiring them as settlement workers. For example, in 1897, Wald hired a widow to sew nurses’ uniforms for the Settlement’s nurse service, so that the young mother could better support her five children. Today, the descendants of those children, the Abrons family, endow the Settlement’s Abrons Arts Center.

Nurses in a row, courtesy of The Henry Street Settlement

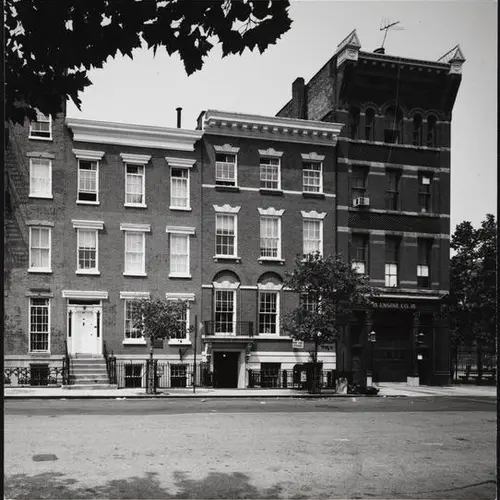

Wald’s approach helped her gain the trust and her neighbors, as well as the financial support of wealthy benefactors. One of Wald’s early top-hatted champions was the banker and philanthropist Jacob Schiff. In 1895, Schiff purchased a brick townhouse at 265 Henry Street to serve as the Settlement’s headquarters.

Wald moved into 265 Henry Street that year, and the Settlement’s work expanded to incorporate visiting nursing, social work, country work and civic work, Wald’s four branches of usefulness. By 1913, the visiting nurse service treated up to 20,000 people throughout the city. In each case, Wald and her nurses strove to give service “on terms most considerate of the dignity and independence of the patients” they cared for.

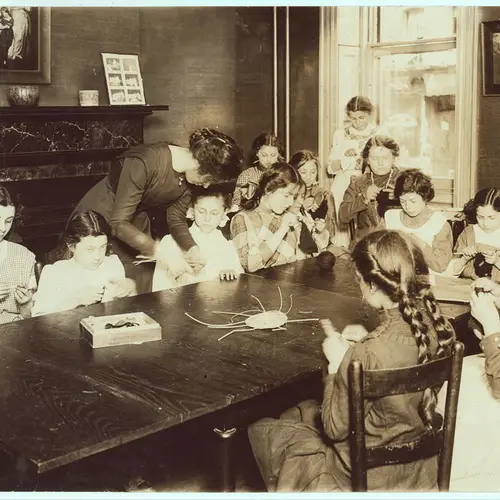

The Settlement’s social work was an effort to bring neighbors together. Henry Street offered children’s clubs, mothers’ clubs, study spaces, arts programming, and both indoor and outdoor recreational facilities, including one of the very first playgrounds in the nation, which Wald fashioned in the Settlement’s backyard in 1902. The playground was a valuable space around the clock: mothers and children relaxed and played in the greenery during the day, while workers and unions organized at the playground in the evening.

Knitting class at The Henry Street Settlement, 1910 via the Library of Congress

Since play and recreation are a natural part of childhood, Wald believed that city kids deserved time in the country where they could shed the concerns of tenement life and experience freedom in nature. In order to help provide such an experience, she undertook “Country Work,” and founded two summer camps in upstate New York. Camp Henry, for boys, opened in 1909. Echo Hill Farm, for girls, opens in 1909.

Wald was also a tireless advocate for social change on the city, state, national, and international levels. She advocated for health, safety, and labor and housing regulations; helped found the Women’s Trade Union League, the Children’s Bureau, and the Outdoor Recreation League; and worked to introduce the nation’s first school nurses, special education classes, and free school lunches into the New York City public school system.

Women’s Trade Union League Labor Parade, New York, 1908 via the Library of Congress

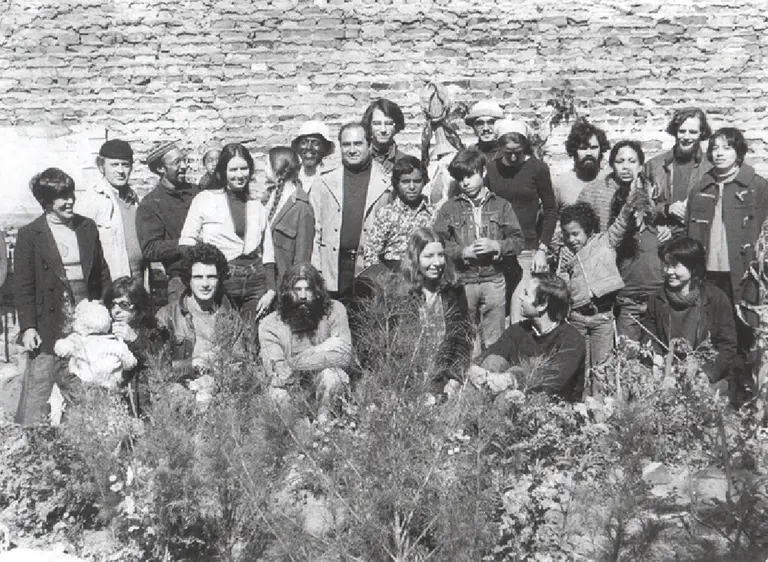

Lillian Wald was an advocate as a neighbor on Henry Street, and as a reformer on the world stage. But at the Henry Street Settlement, the neighborhood and the world were one. At the settlement, Wald created a “culture of connection” that welcomed people from across the street and around the world to exchange ideas across the dining room table. Local garment workers and labor organizers were joined at the Settlement’s dining room table by reformers like Jane Addams and Jacob Riis, moneyed philanthropists like Felix Warburg and Henry Morgenthau Sr., Washington insiders like Eleanor Roosevelt and Frances Perkins, and international leaders like Emmeline Pankhurst and Ramsay Macdonald.

At Henry Street, such an assemblage was the only kind that made sense. “How absurd,” Wald asked, “are frontiers between honest thinking men and women of different nationalities or different classes?” Fittingly, in 1909, 200 reformers led by W.E.B Du Bois met in Henry Street’s dining room to found the NAACP, and “enlist in the fight for humanity and democracy at home.”

Ultimately, it was the cause of common humanity that drew people to the Settlement. Wald explained in 1934, “Presidents and prime ministers, the leaders or the martyrs of their day…from Ireland, Britain, Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Mexico, India, have found their way to the House, not because of any material quest, but to seek sympathetic understanding of their desires for a freer life for their fellow men…We have found that the things which make men alike are finer and stronger than the things that make them different.”

Lillian Wald and Jane Addams, courtesy of The Henry Street Settlement

Today, the Henry Street Settlement honors Wald’s legacy of human connection, social advocacy, and active service. The Settlement continues to fight for fair housing, employment, education, and nutrition in New York City and serves over 60,000 people every year through social service, arts and health care programming at 18 locations on the Lower East Side and more than 20 public schools and community organizations.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.