From stationery store to the famous blue box: The 180-year history of Tiffany & Co.

The recent shake-up at Tiffany, involving the replacement of CEO Frederic Cumenal and the departure of its design director, is said to be predicated on disappointing sales and a resultant decline in share prices. Since last fall, many upscale shops in the area have complained about a negative impact they felt was caused by the hullabaloo around Trump Tower—both rubber-necking and security barricades. A change in marketing emphasis toward a younger consumer—witness the hiring of Lady Gaga for advertising—and designs reflecting that shift are reportedly in the offing to reverse disappointing balance-sheet figures. Not everyone is worried, though. Tiffany & Co. has weathered many a storm in its 180 years, and the ambiance on the floor is still serene, the merchandise still beautiful. For a sense of perspective, and just in time for Valentine’s Day, 6sqft looks at Tiffany’s history.

Wander by Tiffany’s today, stroll inside and catch a look at the enormous yellow diamond displayed on the main floor. It’s called the Tiffany Diamond, and you may recognize it from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” as Audrey Hepburn wore it in publicity photographs for the 1961 film. Reset into a necklace with white diamonds in 2012 and as nearly perfect as they come, this stunning hunk of ancient carbon was first acquired by Tiffany from the Kimberley diamond mines in South Africa in 1878. The stone was cut from 287.42 carets to 128.54 carets with 82 facets, according to the company—almost a 45 percent reduction in weight—but it’s a good bet the bits that fell off were put to good use in pieces of jewelry for sale. (In case you’re tempted to buy it for your valentine, forget it—this jewel is not for sale.)

Long ago as that stone’s arrival is, the company has been around for longer—since 1837, in fact. A wealth of information about the early years of Tiffany & Co. was unearthed and divulged by Michael John Burlingham, a great-grandson of Louis Comfort Tiffany in his book about his grandmother, “The Last Tiffany, a Biography of Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham.”

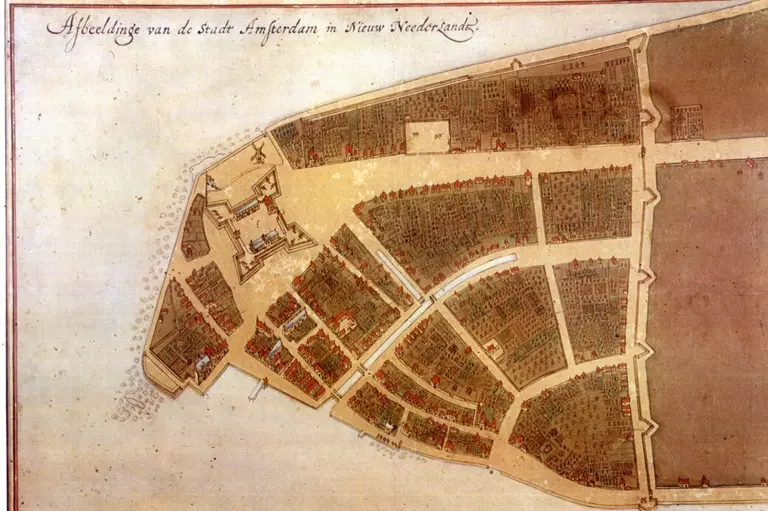

Burlingham’s great-great-grandfather, Charles Lewis Tiffany, was born in 1812 in Connecticut, and from a young age worked for his father, a manufacturer of cotton goods. Young Charles traveled to New York on business from time to time, liked the city and, with John Young, soon to be his brother-in-law, and a $1,000 stake from Charles’s father, rented a four-story building at 259 Broadway at the southwest corner of Warren Street. That was 1837; Charles was 25, but he was already known for his bookkeeping skills and an entrepreneurial spirit. The Tiffany shop was next door to the A.T. Stewart & Co. department store and across from City Hall, answering the prescription for “location, location, location.”

From the beginning, Tiffany & Young, as it was known, catered to the carriage trade, specializing in stationery and goods from the Far East. Burlingham tells us that Charles, clever boy that he was, would go down to the docks when ships from Asia came in with their supply of goods, and dealt there with ships’ captains, who sold privately a better stock than they shipped, matching the kinds of luxury goods Tiffany mainly dealt with. In the 1840s, the store included costume jewelry, which was often disparaged as “paste.” But as many know, costume jewelry can also be luxurious and costly, and Tiffany’s probably was.

Also in the 1840s, the enterprise was joined by a third partner, Charles’s cousin J.L. Ellis, who brought an infusion of cash with him. The name was changed to Tiffany, Young & Ellis, and John Young began to make yearly buying trips to Europe. An 1845 catalog shows perfumes, sealing wax, art engravings, cutlery, tea and coffee services and jewelry. It also stipulated that items were sold for fixed prices—before then bargaining had been the rule—and cash only, no credit. By 1847, the shop had moved to 271 Broadway opposite the Irving House Hotel, a good spot from which to lure wealthy out-of-town shoppers.

One of them was the world-famous diva Jenny Lind, who was appearing in New York for a series of performances and staying at the Irving House hotel, across from the store. She dropped in one day and ordered a tankard for the captain of the ship that had brought her to New York, and Charles reciprocated by giving her a drinking vessel that Burlingham describes as “a mermaid rising from a foaming sea formed the handle; Triton’s tail, the finial of the lid; and a rainbow…arced across the tankard itself.” She loved it and ordered a number of copies. It was the first in a series of silver trophies Tiffany & Co. has manufactured ever since, including today’s Vince Lombardi Trophy for the winner of the National Football League Super Bowl.

Louis Comfort Tiffany (Comfort was his grandfather’s first name) was born in 1848, the first son to survive. Much was hoped and expected of him. When he turned out to be the dreamy, artistic type without a commercial sensibility, however, he was sent to military school, where he suffered but nonetheless improved his ways, Burlingham writes, and improved them enough that years later his father felt he could contribute to the family endeavor as a designer.

In the winter of that same year, John Young and another man sailed for France on a buying trip. By chance, their arrival coincided with the fall of Louis Philippe, and members of the aristocracy panicked, selling off everything they could, including jewelry, for whatever price they could get. Unable to communicate with Charles, John Young went ahead and bought jewels hand over fist—emeralds, diamonds, rubies, pearls—most of it in loose stones, including some from the French Crown. Among the haul was a stomacher owned by Marie Antoinette, a large, decorated triangular piece worn as the center of a bodice. Often the most important piece of a garment, this one was covered with jewels.

That was all it took. Tiffany began designing its own jewelry with those stones and discontinued costume jewelry. Three years later, John Young inherited money from his father and retired, Charles bought out Ellis and the enterprise became Tiffany & Co.

Burlingham tells us that in 1865, when Louis graduated from his detested military school, he spent his time drawing and painting, and Charles gave up hope that his eldest son would follow in his footsteps. Instead, Louis enrolled in the National Academy of Design, studied for a year in Paris and excelled to the point where the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 selected eleven of his works to show.

He was also experimenting with glass, a medium he was to become associated with from then on. As Burlingham says, Louis’s “incessant experimentation and reckless expenditure of capital stretched the technical vocabulary of glass to new limits, achieving the fluent, mature style for which his windows are famous.” In 1875, more than 4,000 new churches were under construction in the U.S., and some of them commissioned the L.C. Tiffany & Co. for windows. Moreover, from the 1870s through World War I, stained glass appeared not only in churches but in residential windows and transoms, skylights, steamships and more.

Initially, though, Louis concentrated on painting nature. His work became so admired that he was asked to design rooms and whole interiors for townhouses and theaters in New York, as well as rooms at the White House for President Chester Arthur. His work in glass and interiors led to a liaison with Lockwood de Forest, a designer importing carved teak from India, and Candace Wheeler, a textile designer, into the Associated Artists. They collaborated with architect Stanford White on the Veterans Room at the 67th Street Armory in Manhattan (a restoration of it was completed in March 2016 and can be seen today).

Meantime, according to a press release from the company, Tiffany & Co. had become “America’s premier silversmith and purveyor of jewels and timepieces.” In 1870, they acquired and demolished an old abolitionist church at 15th Street on the west side of Union Square to replace it with a five-story, 90-foot tall, cast iron building, an early example of that kind of architecture in the city. (It still stands, stripped of its exterior detail and reclad in black glass for residential use a few years ago. If you look closely, through the glass you can still see the arched openings in the original facade.)

The store remained on Union Square until 1905, when work was completed on a building designed by Stanford White in the Italian Renaissance style at 37th Street and 5th Avenue. It is also extant and was designated a New York City landmark in 1988.

In the late 1880s, a competitive spirit developed between Charles and Louis Tiffany. In 1889, both the company and Louis showed at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, and four years later they both again showed at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, visited by 27 million people. Tiffany & Co. picked up 56 medals, Louis 54. It was then that Louis resolved to pursue experiments in blown glass, working on free-blown flower-form vases and development of the iridescence associated with Favrile glass. In the 1900 Paris Exposition, Louis was honored for this work and acknowledged as the new leader worldwide of this decorative style.

Two years later, Charles Lewis Tiffany died. Louis became the company’s first art director but continued with his other businesses. His Tiffany Glass Company never turned a profit, but it lasted a few years beyond his death in 1933.

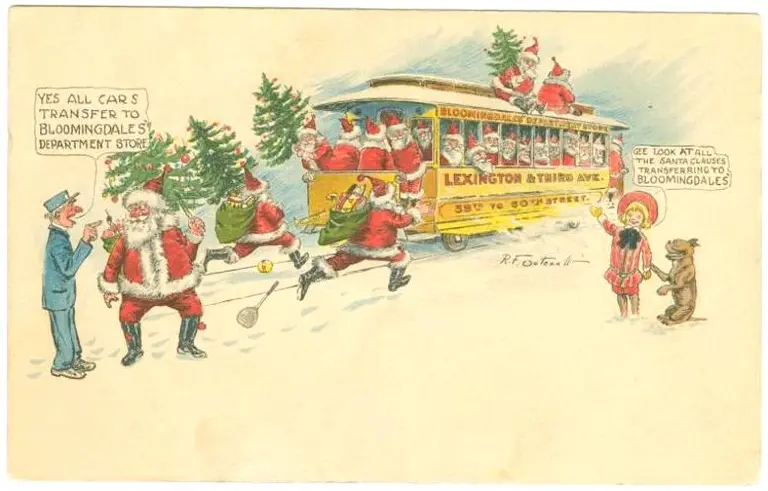

Tiffany & Co., on the other hand, continued to flourish, employing other great designers, such as Jean Schlumberger, Elsa Peretti and Paloma Picasso, and producing china for the White House and connoisseurs of fine living everywhere. In 1940, they moved into their current flagship on Fifth Avenue between 56th and 57th Streets, today sharing the east side of the avenue with Trump Tower. The Art Deco-inspired granite and limestone building boasts stainless steel doors and is adorned with a nine-foot bronze statue of Atlas shouldering a clock.

Tiffany & Co. this past holiday season, via 6sqft

Security barricades and general to-do around Trump Tower spread to Tiffany’s and may have reduced the usual amount of foot traffic to the store, possibly accounting for a 14 percent drop in holiday-season sales in 2016, as reported by Forbes magazine. Nevertheless, silverware, crystal, jewelry and personal accessories are all still produced and sold in the company’s approximately 300 stores, through its catalog and online. It looks as though Tiffany & Co. will outlast us all.

+++

RELATED:

- Tiffany Stained Glass Window Found in a Salvage Yard Reveals a Piece of Upstate History

- The ‘empty mansions’ of Huguette Clark: Luxury and mystery of an era past

- FAO Schwarz and the End of an Era: Looking Back at the World’s Most Famous Toy Store

All images courtesy of Tiffany & Co. unless otherwise noted