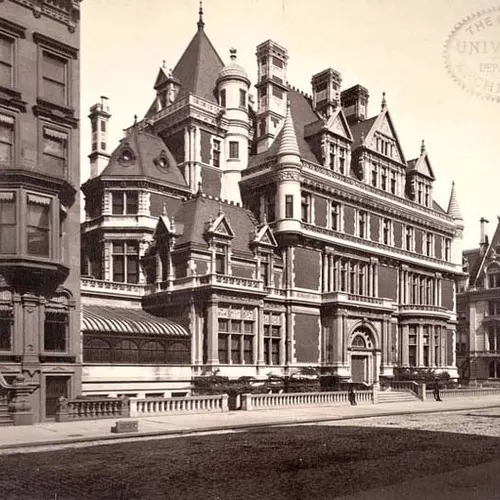

A guide to the Gilded Age mansions of 5th Avenue’s millionaire row

The Cornelius Vanderbilt II Mansion on 57th Street and 5th Avenue, now demolished. Photo via A.D. White Architectural Photographs, Cornell University Library.

New York City’s Fifth Avenue has always been pretty special, although you’d probably never guess that it began with a rather ordinary and functional name: Middle Road. Like the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan for Manhattan, which laid out the city’s future expansion in a rational manner, Middle Road was part of an earlier real estate plan by the City Council. As its name suggests, Middle Road was situated in the middle of a large land parcel that was sold by the council in 1785 to raise municipal funds for the newly established nation. Initially, it was the only road to provide access to this yet-undeveloped portion of Manhattan, but two additional roads were built later (eventually becoming Park Avenue and Sixth Avenue). The steady northwards march of upscale residences, and the retail to match, has its origins where Fifth Avenue literally begins: in the mansions on Washington Square Park. Madison Square was next, but it would take a combination of real-estate clairvoyance and social standing to firmly establish Fifth Avenue as the center of society.

Mrs. Astor’s home via Wikimedia

Mrs. Astor’s home via Wikimedia

The catalyst for Fifth Avenue’s transformation came in the form of the Astor family. Patriarch John Jacob Astor had purchased large swaths of Manhattan in the aforementioned land sales, allowing William Backhouse Astor Sr. to present his son and the new Caroline Astor (née Webster Schermerhorn) with a parcel of land on 34th Street and 5th Avenue as a wedding gift in 1854.

Old money didn’t need to flaunt, however, so the resulting home was a rather modest brownstone. But the arrival of upstarts A.T. Stewart across the street forced Caroline into action. Following extensive interior renovations in the French Rococo style, the first “Mrs. Astor’s House” was born. It was also here that societal standing was attained and lost, amidst the famous 400 (named so because it was simply how many people could fit into Mrs. Astor’s ballroom). The ballroom, sumptuously appointed with floor-to-ceiling artwork and a massive chandelier, was built in a new wing that replaced the stables.

With new fortunes being made overnight in the new center of world commerce that was New York, it was only logical that the new millionaires each needed their own mansions along 5th Avenue.

Here is a guide to the Gilded Age mansions on 5th Avenue, both those still standing and those lost.

The Vanderbilt Triple Palace: 640 and 660 Fifth Avenue and 2 West 52nd Street: Demolished

Image from Public Domain from the A. D. White Architectural Photographs Collection, Cornell University Library

Image from Public Domain from the A. D. White Architectural Photographs Collection, Cornell University Library

These three townhouses, built in 1882 and known as the “Triple Palaces,” were given to the daughters of William Henry Vanderbilt, son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. These buildings occupied the entire block between 51st and 52nd Street on 5th Avenue, along with the corner of 52nd Street. Henry Clay Frick was so taken in by the construction of 640 5th Avenue that he is quoted to have said, “That is all I shall ever want” on a drive past the Triple Palaces with his friend Andrew Mellon.

Indeed, Frick set out to emulate the art collection of Vanderbilt and even moved into 640 5th Avenue in 1905 with a 10-year lease, while George Vanderbilt was preoccupied with building the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. He would have bought the house if William H. Vanderbilt’s will had not barred George from selling the home and art outside of the family. Later, via a loophole, the property and artwork was able to be sold by Vanderbilt’s grandson to the Astors, who in turn sold the holdings in the 1940s.

The buildings, considered anachronistic, were demolished and replaced by skyscrapers. Today, they are home to retailers H&M, Godiva, and Juicy Couture, while Frick’s art collection and mansion remain intact (including the secret bowling alley underground) on 70th Street and 5th Avenue.

+++

Morton F. Plant House and George W. Vanderbilt House, 4 E. 52nd Street, 645 and 647 Fifth Avenue

Via Wikimedia

In 1905, Architect C.P.H Gilbert built this American Renaissance mansion at the corner of 52nd Street and 5th Avenue for Morgan Freeman Plant, son of the railroad tycoon Henry B. Plant. Today, it’s been converted into the Cartier store but the original front entrance of the home was on 52nd Street. Next door were mansions of George W. Vanderbilt, son of William Henry Vanderbilt. The homes, designed by Hunt & Hunt also in 1905, were known as the “Marble Twins.” The AIA Guide to New York City describes both the Plant and Vanderbilt homes as “free interpretation[s] of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century palazzi.” The Vanderbilt mansion at 645 was demolished but 647 remains, now the Versace store.

+++

William K. Vanderbilt Mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue: Demolished

The William K. Vanderbilt Mansion. Image source: Library of Congress

The William K. Vanderbilt Mansion. Image source: Library of Congress

Diagonally across from the Morton F. Plant House was the William K. Vanderbilt Mansion, which William’s wife, Alva Vanderbilt, commissioned from Richard Morris Hunt in a French-Renaissance and Gothic style in 1878. The mansion, affectionately referred to as the Petit Chateau, was part of Alva Vanderbilt’s tenacious attempt to break into the 400 society, in a time when new money was still looked down upon.

According to the book Fortune’s Children by Vanderbilt descendant Arthur T. Vanderbilt II, architect “Hunt knew his new young clients very well, and he understood the function of architecture as a reflection of ambition. He sensed that Alva wasn’t interested in another home. She wanted a weapon: a house she could use as a battering ram to crash through the gates of society.” The interiors were decorated from trips to Europe, with items from both antique shops and from “pillaging the ancient homes of impoverished nobility.” The facade was of Indiana limestone and the grand hall built of stone quarried from Caen, France.

But a grand house enough wasn’t enough, and she battled back with a ball of her own in which she invited more than the usual 400. 1,200 of New York’s finest were invited to this fancy dress ball in 1883, but not Mrs. Astor, who promptly, and finally, called on Alva’s new “upstart” home to guarantee an invitation to the ball for her and her daughter.

The ball was as incredible as promised with the New York Press head over heels. The New York Times called is “Mrs. W.K. Vanderbilt’s Great Fancy Dress Ball” where “Mrs. Vanderbilt’s irreproachable taste was seen to perfection in her costume.” The New York World went as far to say that it was an “event never equalled in the social annals of the metropolis.” At a $250,000 cost, this social coup solidified the Vanderbilt family in New York society.

Sadly, the mansion was demolished in 1926 after being sold to a real estate developer and in its stead rose 666 Fifth Avenue. Today, you’ll find a Zara occupying the retail floor.

+++

680 and 684 Fifth Avenue Townhouses: Demolished

Photo of the Webb and Twombly mansions via Wikimedia

Photo of the Webb and Twombly mansions via Wikimedia

These two townhouses by architect John B. Snook were built in 1883 for Florence Adele Vanderbilt Twombly and Eliza Osgood Vanderbilt Webb as gifts from William H. Vanderbilt. Florence lived in 684 until 1926 when she upgraded to a new mansion further north along Central Park. The Webbs sold 680 to John D. Rockefeller in 1913. Both were demolished for a skyscraper that has The Gap as its anchor tenant.

+++

The Cornelius Vanderbilt II Mansion 742-748 Fifth Avenue: Demolished

Image via Library of Congress

Image via Library of Congress

Cornelius Vanderbilt II used the inheritance from his father the Commodore to purchase three brownstones on the corner of 57th Street and 5th Avenue, demolish them and build this mansion. According to the book Fortune’s Children by Vanderbilt descendant Arthur T. Vanderbilt II, it was “common belief that Alice Vanderbilt set out to dwarf her sister in law [Alva Vanderbilt]‘s Fifth Avenue chateau, and dwarf it she did.” Cornelius’ mansion was allegedly the largest single-family house in New York City at the time, and its brick and limestone facade further differentiated it from its neighbors.

It gradually became eclipsed by even larger commercial skyscrapers and was sold to a realty corporation in 1926, who demolished the home and built the Bergdorf Goodman department store in its place. Still, a fun expedition is to track down the remnants of this mansion which are now scattered around Manhattan, including the front gates that are now in Central Park, sculptural reliefs now in the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, and a grand fireplace now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In Fifth Avenue’s evolution from mansions to luxury retail, two factors sustained its elegance, according to the AIA Guide to New York City:

“The Fifth Avenue Association (whose members had fought billboards, bootblacks, parking lots, projecting signs–even funeral parlors), and the absence of els or subways. To provide a genteel alternative for rapid transit, the Fifth Avenue Transportation Company was established in 1885, using horse-drawn omnibuses until 1907, followed by the fondly remembered double-deck buses. Once upon a time even the traffic lights were special: bronze standards with neo-Grec Mercury atop, subsidized by the Fifth Avenue Association concerned with style.”

+++

Editor’s note: The original version of this article was published on August 22, 2017, and has since been updated.

RELATED: A Guide to the Gilded Age Mansions of 5th Avenue’s Millionaire Row – Part II

Michelle Young is the founder of Untapped Cities, a publication and tour company about urban exploration and discovery in New York City. She is also an adjunct professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Follow her on Twitter @untappedmich.

Explore NYC Virtually

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Fantastic read! Just love it. Can’t wait for the next piece.

so interesting. especially about there being a distinction between “old” and “new” money. can’t wait to read the 2nd entry.

Great Post. I enjoy all the mansions from Stanny and RM Hunt especially!

Thank You. Enjoyed it immensely. I see references to one of the Vanderbilt nephews : Arther Vanderbilt who penned “Fortunes Children” and must read that. I suggest if at all possible get a hold of Corneliuse Vanderbilts book “Farewell to Fifth Ave” and read it. It’s a lot of fun and done in the witty style. He lays out the basic “rules” about society and tattles a lot. It’s a blast. He lost his piece of the fortune locking horns with some of the big -boys like Willium Randolph Hurst – Arthur Brisbain and the other monied set. He attempted to open his own newspaper and paid dearly (to protect the family name -was forced to give up what was his inheritance to pay the debt) He listened to Lord Northcliff ‘s advice and amusingly says he thought he could just order up a few presses to get started, not realizing it takes months to build. But he lays out the vicious battle between himself and the other tycoons of newspaper. You can’t help but love this redoubtable fighter. And he wanted to be just a journalist/ newspaper man. It’s a great story and he describes the social set in details. He grew up in the mansion and I remember his stating there where mansions or high set mansions from 14 st. all the way up to 110 st. Plaza. Anyway thank you again.

From one writer to another (and a North Carolina native obsessed with The Biltmore Estate, and former Manhattanite) this was a highly entertaining and engrossing story. I can’t wait to read Part II. A most excellent article Michelle. Kelly Merritt

Where is link to next post? Please tell me you did it. I was looking forward to more!!

Cornelius Vanderbilt II was the grandson (not the son as stated in this piece) of the Commodore. CV II’s father was William Henry Vanderbilt (the Commodore’s eldest son). The Commodore did have a son named Cornelius, but his full name was Cornelius Jeremiah Vanderbilt and he committed suicide in 1882.

Maybe someone will see this but how much would this house have cost in 1883.

Willie K. and Alva Vanderbilt’s mansion at 660 is a good study for George W. Vanderbilt’s massive Biltmore House in Asheville, NC, from the French Renaissance-inspired architecture down to the Indiana limestone facing. If you want a good idea of what 660 looked like (greatly expanded), visit Biltmore!

Great New York history lesson, Please continue!

Terrific informative article with wonderful photos of residential single family scaled buildings that now appear as only ghosts to all be relaced by faceless monoliths.

So interesting to read all this after having taken a stroll down Fifth Avenue. I’ll be linking back to your informative post. Thanks for all the info.

Thanks. Good read after watching the gilded age

Where did the money come from?

good