Race Drives Gentrification and Neighborhood Boundaries, Study Finds

Photo by brandon king cc

Focusing in on just race can be taboo when looking at gentrification, but a new study finds that an area’s racial composition is actually the biggest predictor of how a changing neighborhood is perceived. CityLab recently dissected the study conducted by sociologist Jackelyn Hwang to find that the way that blacks and whites perceive and talk about change in their neighborhood is often wildly different. This gap in perception has wide-reaching effects for changing neighborhoods because not only does it polarize the individual groups, but it can also have a tremendous effect on where neighborhood boundaries are drawn and investment is distributed.

Photo: Blue Bottle Coffee

Photo: Blue Bottle Coffee

In 2006, Hwang took a look at a gentrifying neighborhood in South Philadelphia that once had an African-American majority and was high in crime and poverty. Hwang’s study sample consisted of 56 residents, equally split between black and white (plus two mixed race residents and two Native American residents), who had either moved into the area between 1990 and the mid-aughts when the city undertook a massive revitalization plan, or who had been living in the area for years prior to this. She also divided her sample not only by race and length of time in the neighborhood, but by education, income and age.

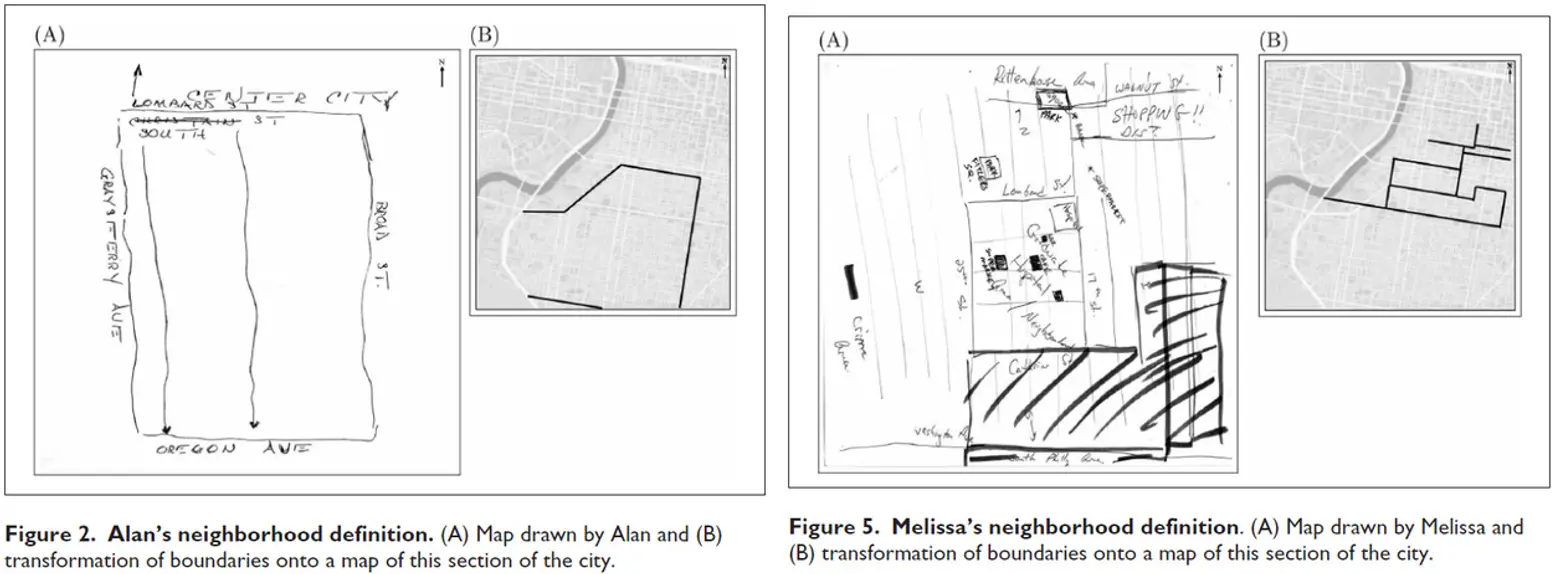

At the most basic level, she found in her interviews that about 23 percent of the white folks she spoke with received a college degree, versus about 10 percent of blacks. She also found that white residents had been in the neighborhood for a median of five years, compared to 23 years for the black residents. But more interestingly, she asked her participants several questions that related back to how they perceived their neighborhood amid all the change and how their fellow residents “gave meaning” to the area. She also asked her participants to draw maps of their neighborhood telling them to place markers and boundaries to denote any hotspots they’ve come to associate with their neighborhood.

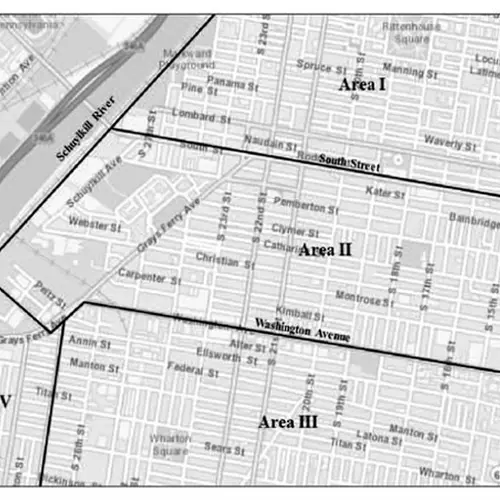

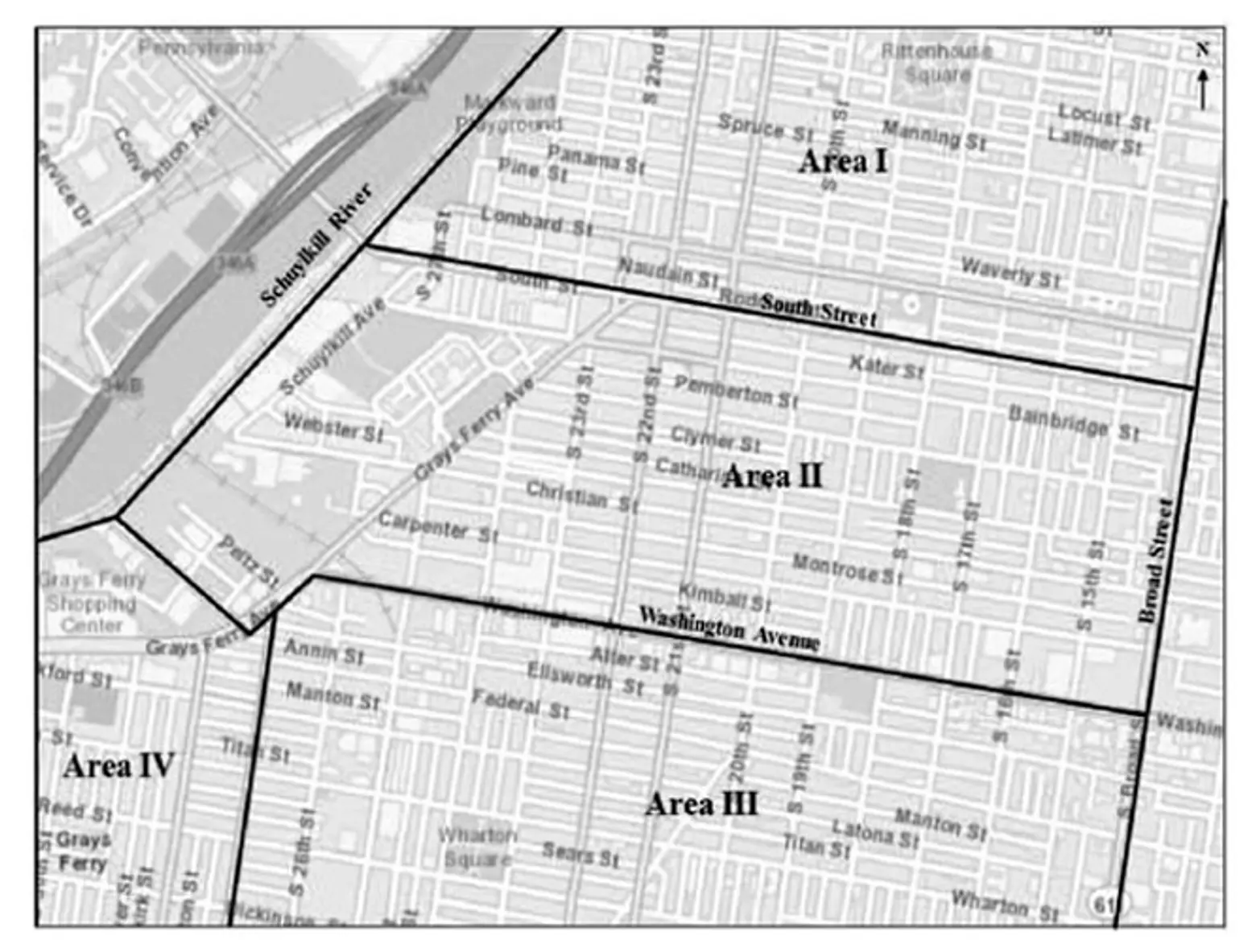

Image: The research site in South Philadelphia. Area II represents the part of the neighborhood statistically showing the most demographic change

Image: The research site in South Philadelphia. Area II represents the part of the neighborhood statistically showing the most demographic change

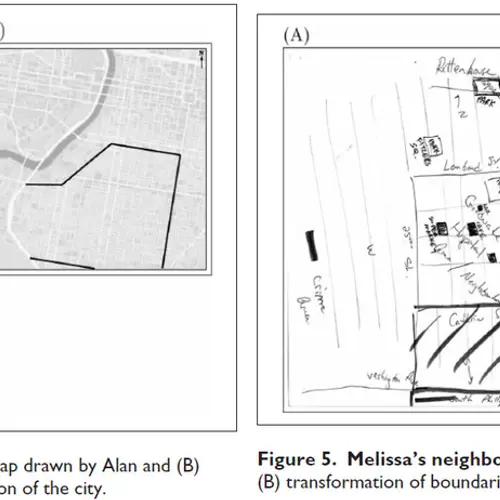

Image: The left map was drawn by Alan, a 59-year-old, black, college-educated, longtime resident; The right map was drawn by Melissa, a 30-year-old college-educated, white resident. Alan’s view of the neighborhood is based on conventional markers like streets, while Melissa’s is far more fluid.

What Hwang found was that black and white residents characterized the neighborhood very, very differently—where one white resident would see crime and change, a black resident would see neither, simply mapping an area based on a street or official landmark, even when evidence suggested there was in fact significant change.

By comparison, something that will be very familiar to us New Yorkers arose when she spoke to white residents. She found that most white residents didn’t associate their neighborhood as being part of “South Philly” as it has been commonly referred to by long-time black residents, but gave it new monikers like “South Rittenhouse” and “G-Ho.” Boundaries for them were instead determined by where they saw favorable change like shopping, coffee shops, and grocery stores. They were also more likely to completely exclude areas they perceived as being crime areas, even if figures showed the areas they singled out were in reality no more crime-ridden than others.

Hwang found that the majority of non-white residents held to traditional neighborhood boundaries to avoid exclusion. “To divide their neighborhood into smaller areas would, in their view, be “inauthentic,” writes reporter Richard Florida in The Atlantic. These responses were consistent across Hwang’s sample when looking at race, even when factoring in how long a person had been in a neighborhood and their level of education.

Ultimately, from speaking with her sample, Hwang came to the conclusion that an individual’s perception of their neighborhood comes from whether or they feel “they fit with the identity associated with a space,” and that they will strategize to “exclude or include others to make the neighborhood identity align with their personal identity.”

As previously mentioned, these observed lines can have a big impact on a neighborhood, especially as city money pours in for redevelopment. How money is distributed across a neighborhood often depends on how lines are drawn, even if they are informal and based mostly on opinion. The subject neighborhood of Hwang’s study saw just this happen. Where her white sample perceived promise was exactly where change won out, and those who failed to make those distinctions–namely the neighborhood’s minority respondents–were displaced. We’ve also seen this time and again in New York City, and it continues to be an issue in today’s rapidly changing neighborhoods like Bed-Stuy, Crown Heights and Harlem.

You can get more details from the report here or over at CityLab.

[Via CityLab]

RELATED:

- Get ‘Em While They’re Cheap: A Look at Crown Heights Real Estate Past and Present

- Quooklyn: The Rise of Ridgewood and Why Your Friends Will be Moving There

- Coffee Culture: Are Neighborhood Cafes the First Sign of Gentrification?