The Urban Lens: Remembering the darkness of Hurricane Sandy five years later

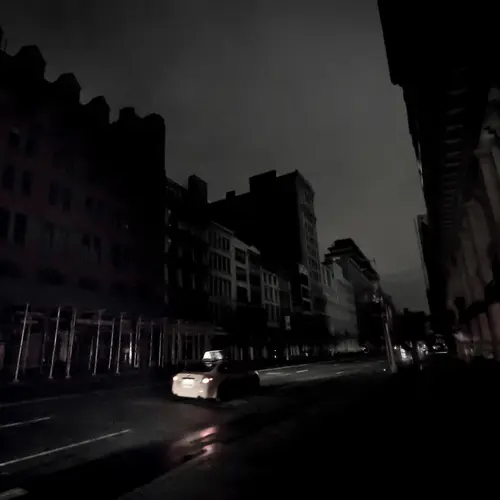

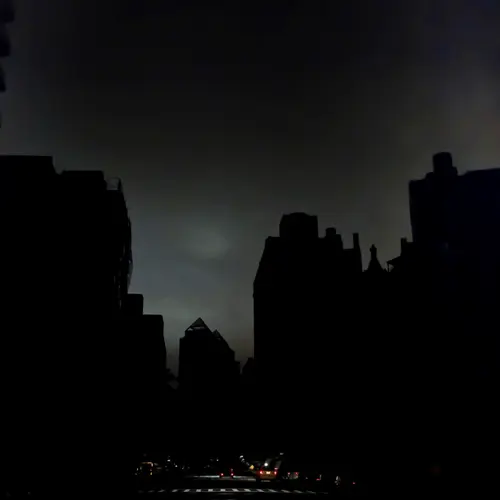

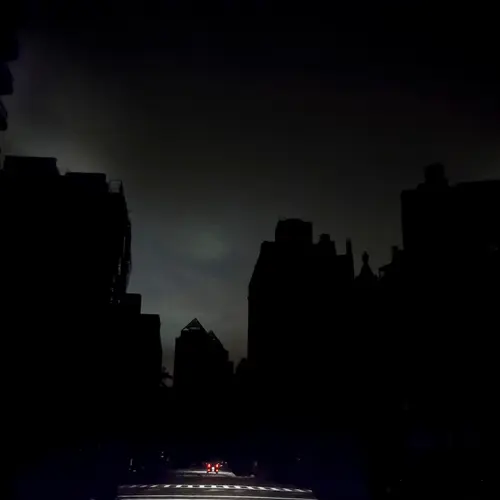

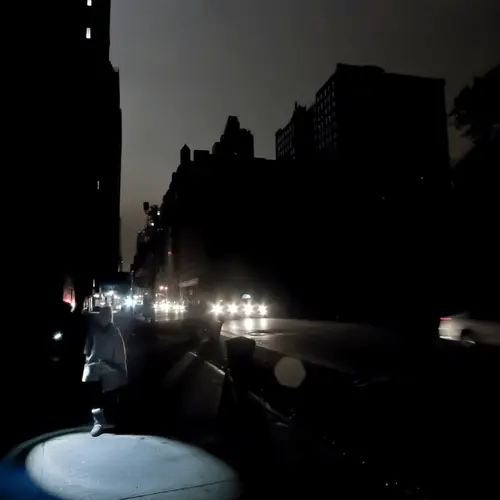

6sqft’s series The Urban Lens invites photographers to share work exploring a theme or a place within New York City. In this installment, Orestes Gonzalez shares his series “Dark Sandy,” photos he took five years ago when lower Manhattan lost power during Hurricane Sandy. Are you a photographer who’d like to see your work featured on The Urban Lens? Get in touch with us at [email protected].

“Never had I seen Manhattan in such darkness… I had to get over there and experience this dark phenomenon with my camera,” says Orestes Gonzalez of his series of photographs taken the night Hurricane Sandy hit New York City. As we now approach the fifth anniversary of the Superstorm, the photos are a reminder of how far we’ve come, and in some cases, how much work still needs to be done. In fact, 20% of the 12,713 families who enrolled in the city’s Build it Back program are still waiting for construction to wrap up or for a property buyout. But despite some of the post-storm issues, in the wake of the disaster, Orestes remembers the “sense of camaraderie” he experienced during those dark times, a trait that New Yorkers have come to be known for.

You say on your site that “as a Baby Boomer,” you’re “attracted to observing institutions that held mystic reverence but failed to evolve.” Can you expand on this a bit and tell us how you’ve achieved this through your photography?

Growing up in ’70’s America, there was a sense that anything was possible. Even after the Vietnam War, our hubris, nationalistic pride, and can-do attitude kept us moving right along. We were seemingly blind to the external forces that were transforming this country. Stiff competition from foreign markets and the impending tech revolution started to fray the fabric of what we were most proud. The manufacturing industries started shrinking, and factories started shutting down. We began to lose our standing in the world to others. A classic example I always refer to is the Kodak Corporation. Once the main source of film for most of the world, Kodak started to lose its footing when Japanese and German competitors deeply cut into their market share. The double whammy digital photography and Kodak’s lackluster attempt to join that world transformed this great influential company into a very minor player in a very short period of time.

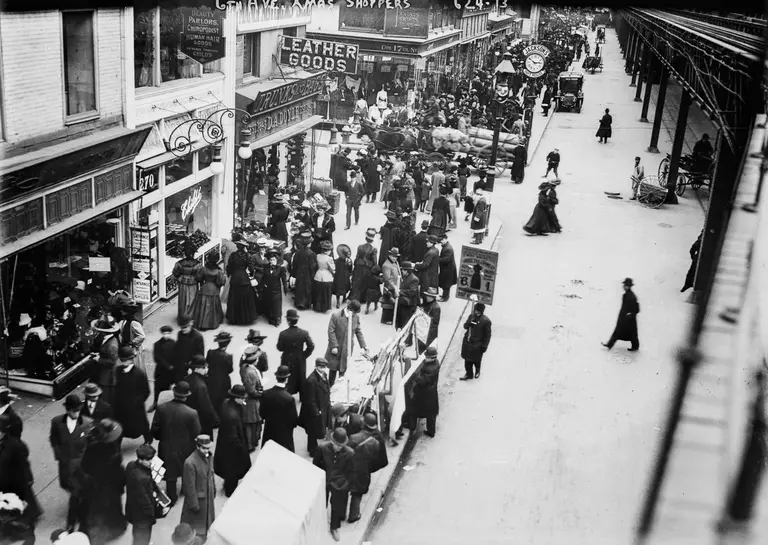

I make images of neglected factories, in cemeteries where monuments to the rich and powerful families that dominated NY industry still exist, and in industrial areas that are being transformed by gentrification. Taking pictures of New York and everything that it stood for in its heyday is what motivates me. For years, I’ve been taking pictures of the Easter Day Parade on 5th Avenue. To me, it still feels timeless. It holds a special place in my memories of what this country represented to so many around the world.

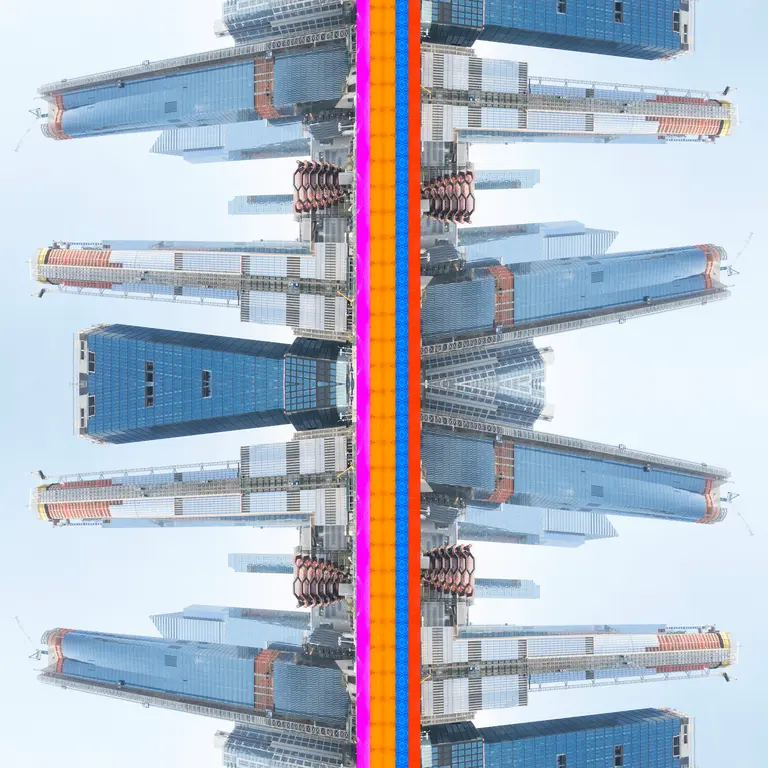

You do a lot of work in your home neighborhood of Long Island City and have a monthly column for Queens/LIC Courier Magazine where you chronicle changes in the area. What do you think makes LIC unique and how have you seen it transform since you’ve lived there?

Long Island City has changed dramatically in the last 20 years. It’s even been called the fastest growing neighborhood in the country! Its uniqueness lies in its proximity to Manhattan and its plethora of subway lines. I miss some of the old businesses that have closed. I also miss how quiet it was on the weekends when all the local manufacturing industries would close and you would have the whole place to yourself.

What was it like taking the “Dark Sandy” series?

It was pretty surreal.

I live in Long Island City, a few blocks from the East River. The impending storm caused a lot of people to evacuate the shoreline and to prepare for the worst. Neighbors sandbagged their entrances and moved their vehicles inland. Luckily, my house was spared from the floods (the river crested just one block away). We never lost power.

When evening fell, I walked over to the East River and looked at the Manhattan skyline. It was dark and foreboding. Never had I seen Manhattan (below 34th street) in such darkness. I desperately wanted to be there, to see it first hand. The subways weren’t working, and there was a vehicular curfew from the outer boroughs into Manhattan. But I had to get over there and experience this dark phenomenon with my camera. I was one of the first cars allowed to cross the Williamsburg Bridge. It was scary to go from the bright lights of Brooklyn to this dark place where the glow of headlights was the only thing keeping you from total darkness. I grew up hearing of the famous Blackout in the ’70’s. I thought this was something special as well.

What do you remember most about NYC during that time?

I remember mostly the sense of camaraderie. Everybody was trying to help out. Because there was so little traffic allowed into Manhattan, the streets were generally empty, and people walked everywhere. In the evening the glow of the headlights in the darkened streets created a creepy tableaux that was very different from the norm.

Any future projects you can tell us about?

My book, “Julios House” was just published by +krisgravesprojects. It’s a story of an underappreciated family member who was never given proper credit for helping save his family from the grips of the Cuban Dictatorship.

Additionally, I am about to embark on a month-long photo essay in Guatemala based on a family reunion of members that haven’t seen each other in over 20 years. Hopefully, a short film will come out of that experience.

Instagram: @setseroz

Website: orestesgonzalez.com

▽ ▽ ▽

You can see more in the gallery below and in Orestes’ video:

Dark Sandy from orestes gonzalez on Vimeo.

All photos © Orestes Gonzalez