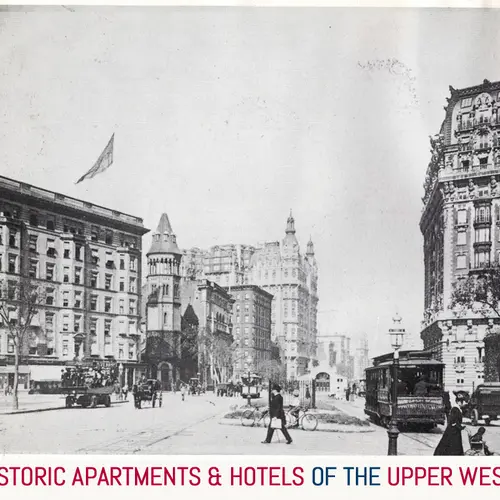

How the Historic Apartments and Hotels of the Upper West Side Came to Be

It’s hard to imagine today that people had to be lured to settle on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, but such was the case at the turn of the 20th century when the first New York City subway line opened. The Interborough Rapid Transit Line (IRT) started at City Hall, with the most epic of subway stations (now closed off to the public except on official Transit Museum tours). The Astors and other enterprising investors owned the land uptown, purchased in a speculative property boom. Now, the question was how to brand the area.

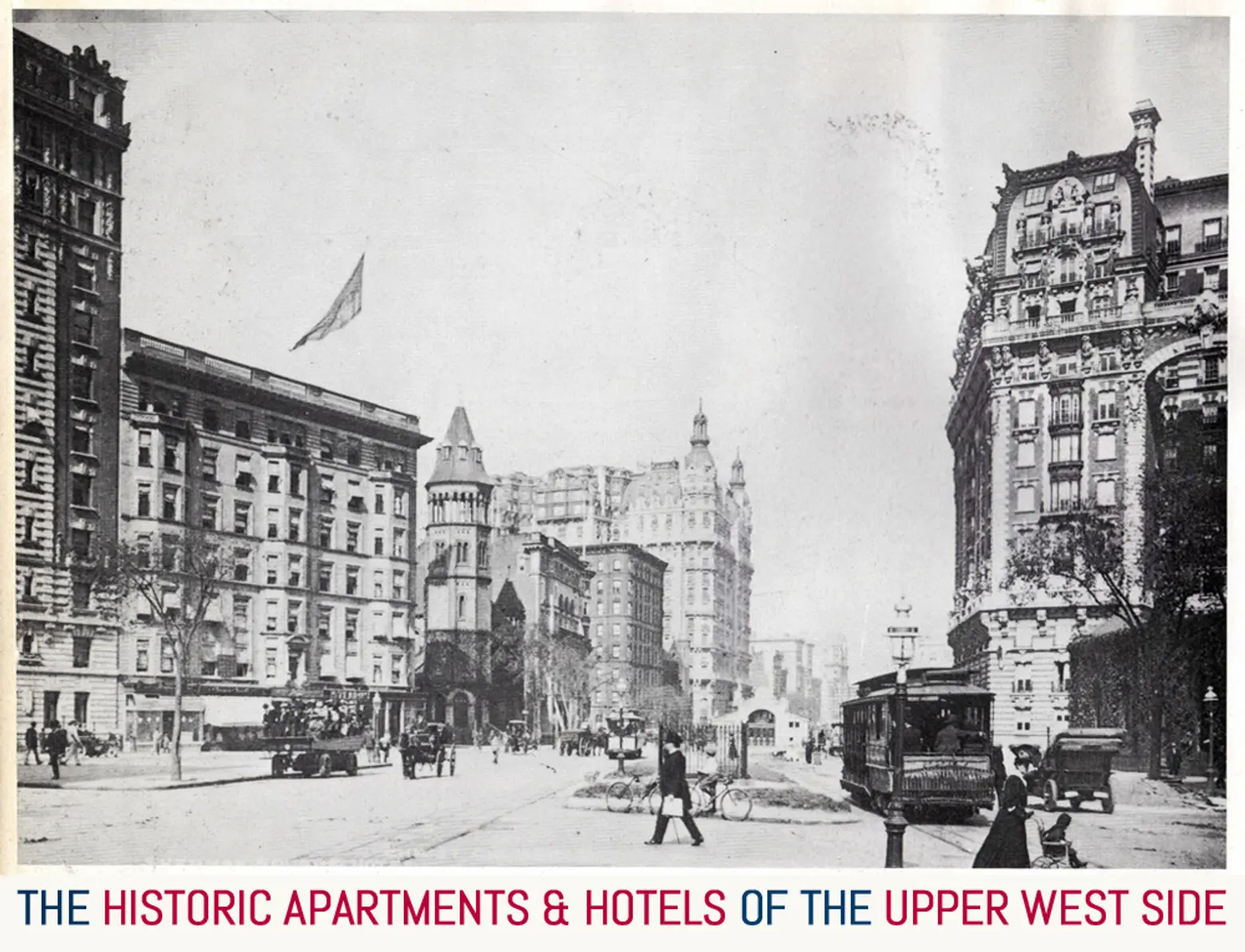

The Ansonia Hotel

Image via Library of Congress

Image via Library of Congress

The Ansonia Hotel went up even before the opening of the subway, from 1899 to 1904. Developer William Earl Dodge Stokes was the so-called “black sheep” of his family–one of nine children born to copper heiress Caroline Phelps and banker James Stocks. Stokes predicted that Broadway would one day surpass the renown of Fifth Avenue to become the most important boulevard in New York City, the city’s Champs-Élysées. The Ansonia Hotel would herald these changing times, located in a prime location on 73rd Street just one block north of the subway station.

One thing to keep in mind is that the term hotel in the time period of the Ansonia meant a residential hotel, more like if you combined today’s luxury apartments with a full-service concierge and housekeeping staff. The French-inspired building, with its mansard roof, contained 1,400 rooms and 230 suites across 550,000 square feet. Pneumatic tubes in the walls delivered messages between staff and residents.

The building was chock full of amenities to make it appealing, including a pool, bank, dentist, physicians, apothecary, laundry, barbershop, tailor, wine, liquor and cigar shop, and flower shop. There were elevators, made by a company formed specifically for the building, and the exterior was clad in fire-proof terra cotta. A wonderful spiral grand staircase of marble and mahogany led up to a skylight seventeen floors up. At maximum capacity, the ballrooms and dining rooms could accommodate 1,300 guests.

The Ansonia was always a place with an off-beat, bohemian reputation and has endured its share of scandal, like the famous White Sox meeting to fix the 1919 World Series, which took place in one of the rooms. It’s period of near abandonment and disrepair in the 1960s and ’70s also serves as a reminder of how even the grandest architecture can be forgotten, and later revived.

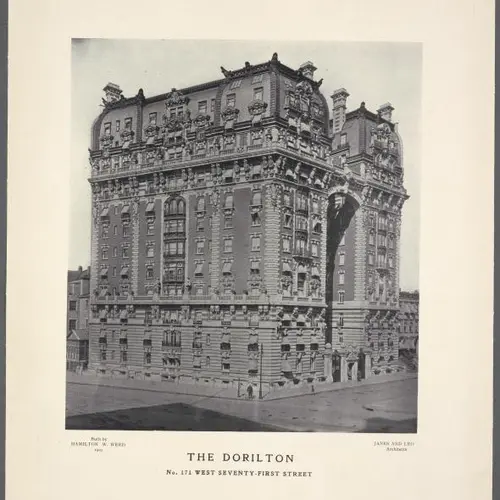

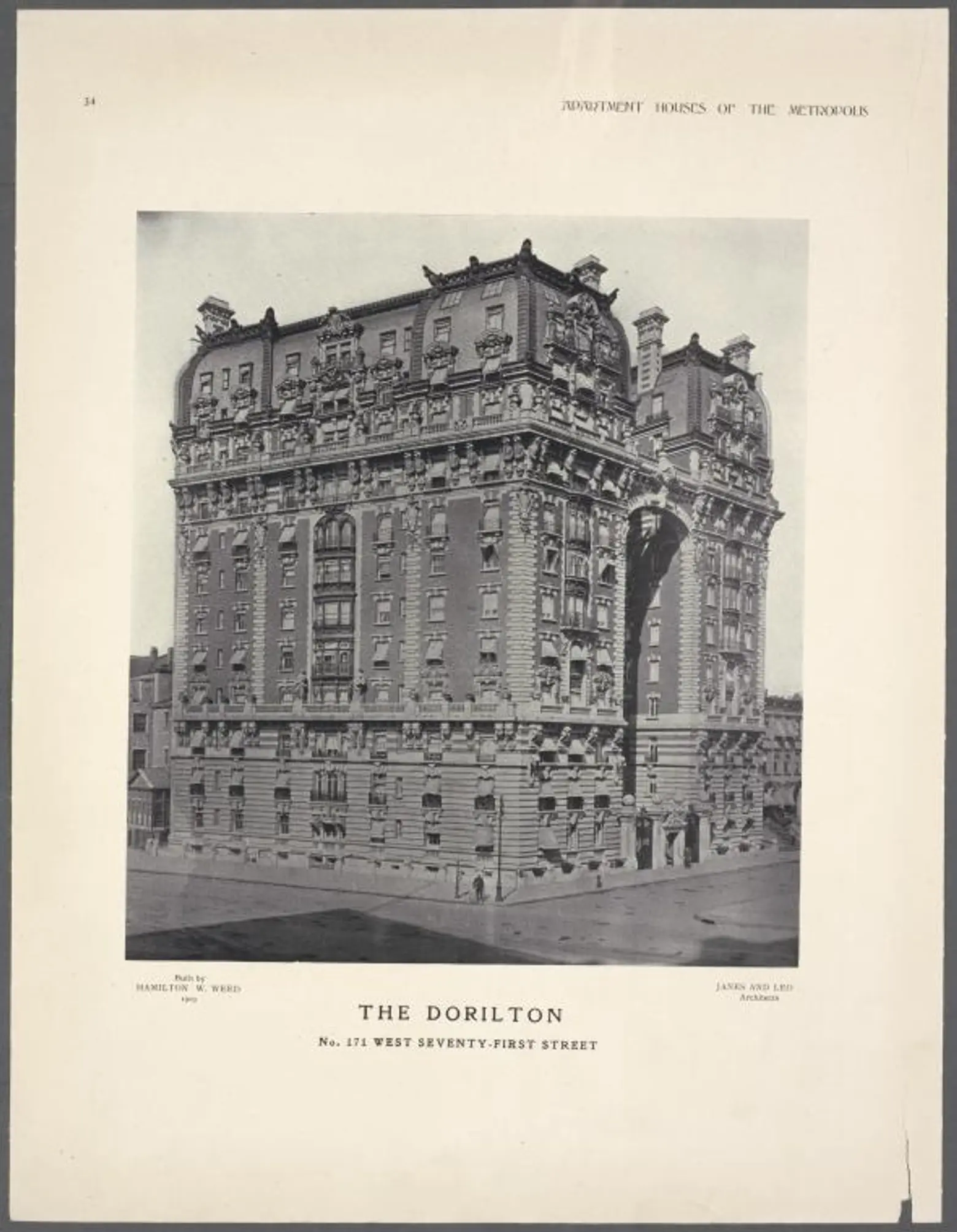

The Dorilton

Image via Library of Congress

Image via Library of Congress

Just south of 72nd Street is The Dorilton, another striking French-inspired apartment building noted for its extreme three-story extension of the mansard roof and a monumental archway high up in the sky. It was built between 1900 and 1902 of limestone and brick, with an iron gateway that once served as a carriage entrance.

Image via NYPL

Image via NYPL

Architectural historian Andrew Dolkart has called The Dorilton the “most flamboyant apartment house in New York” while the Landmarks Preservation designation gives more reserved praise, as “one of the finest Beaux-Arts buildings in Manhattan.”

On a fun note, the Dorilton has been a popular apartment for artists and musicians due to its large rooms and soundproof construction.

The Apthorp

For those that wanted a more private living style and garden space, The Astors had an ingenious architectural solution. Take a palazzo-style building and carve the inside out, leaving garden space in the courtyard. According to Julia Vitullo-Martin, this move was certainly a gamble:

In a city that so cherished its real estate values that it had divided early 19th-century Manhattan into a grid of blocks composed of tiny lots, the courtyard developer was willingly giving up thousands of square feet to communal use. The developer hoped, of course, that the reward would come in the form of high rents paid by prestigious tenants.

The benefits for residents of The Apthorp came in the form of more light and air to the apartments, and a European feel at a time when the city’s elite still strongly identified with the continent.

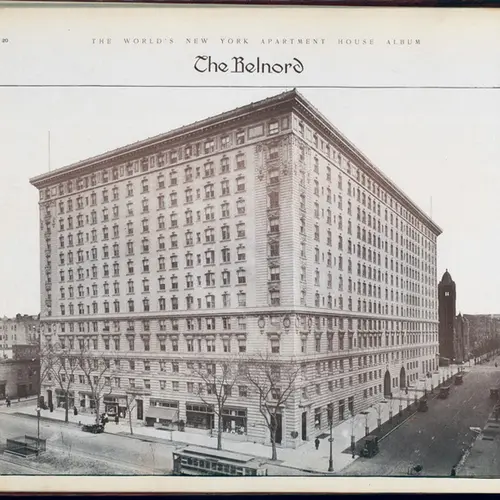

The Belnord

Image via NYPL

Image via NYPL

The Belnord is also an Astor development and like The Apthorp, it has arch entrances and central courtyard. Proportionally, it may not be the more pleasing of the two but it has a distinctive architectural element that sets it apart, according to the New York City landmarks designation report: the windows are of all different shapes and sizes, and “further differentiated by varying their enframements and embellishments.”

The Dakota

Image via Library of Congress

Image via Library of Congress

Popular legend has it that The Dakota was so named because when it was built, in 1884, it was so far north it might as well have been like living in the Dakotas. Another theory is that Edward Clark, the building developer and former president Singer Sewing Machine company, chose the name because of his penchant for the Western states. The Dakota was designed by architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, who also would do the Plaza Hotel. Like The Ansonia, which came later, The Dakota was full of amenities. For meals, residents could eat in the dining room or have the meals delivered to their apartments. There was a full housekeeping staff, gym, playroom, tennis and croquet court. The top two floors were originally just for the housekeepers. It’s legend continues, with illustrious tenants like Lauren Bacall and ill-fated ones, like John Lennon who was assassinated there.

Graham Court

Back in the day, the Astors were also interested in Harlem and built the 800-room Graham Court starting in 1898. It was for whites only and did not integrate until sometime between 1928 and 1933—one of the last buildings in Harlem to do so. Once that took place, important African American community leaders moved in. Hard times befell Graham Court from the 1960s to the 1980s, with a string of owners unable to pay the taxes on the building, let alone maintain the building. It was purchased in 1993 by Leon Scharf, a real estate investor who immediately put in $1 million in improvements. Scharf sold a majority stake to the Graham Court Owners’ Corporation in 1993.

It is to the credit of the Astors and other entrepreneurs of the era for the vast, long term foresight that spurred the development of the Upper West Side. These larger apartment complexes that reference European architecture are landmarks in their own right and continue to serve as beacons amidst the Upper West Side fabric today.

***

Michelle Young is the founder of Untapped Cities, a publication and tour company about urban exploration and discovery in New York City. She is also an adjunct professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and is the author of a forthcoming book on the history of Broadway from Arcadia Publishing. Follow her on Twitter @untappedmich.