Meet the women who founded New York City’s modern and contemporary art museums

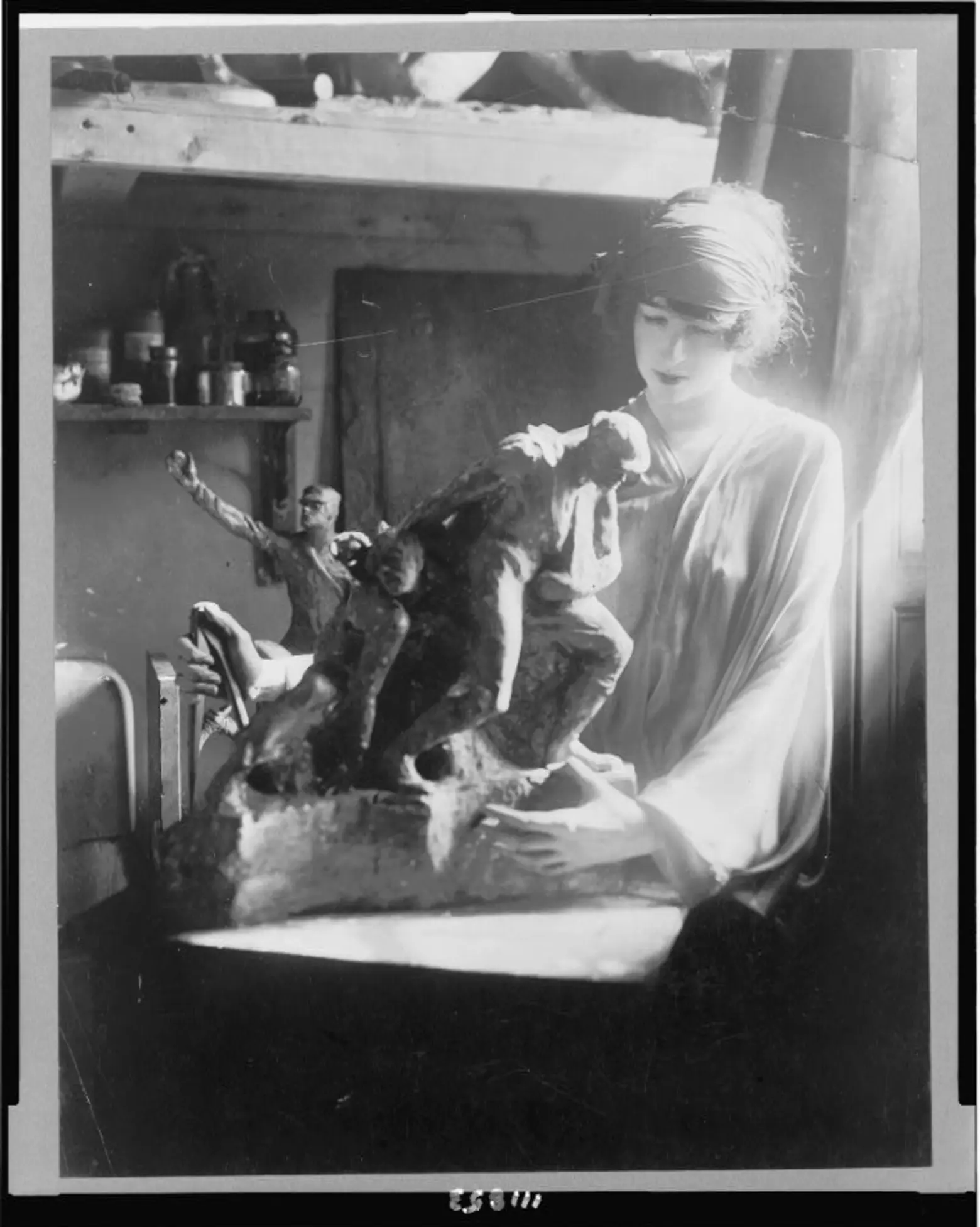

“Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, half-length portrait, standing with statue of soldiers,” 1920, via, The Library of Congress

When the first Armory Show came to New York City in 1913, it marked the dawn of Modernism in America, displaying work by Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse, and Duchamp for the very first time. Not only did female art patrons provide 80 percent of the funding for the show, but since that time, women have continued to be the central champions of American modern and contemporary art. It was Abby Aldrich Rockefeller who founded MoMA; Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney the Whitney; Hilla von Rebay the Guggenheim; Aileen Osborn Webb the Museum of Art and Design; and Marcia Tucker the New Museum. Read on to meet the modern women who founded virtually all of New York City’s most prestigious modern and contemporary art museums.

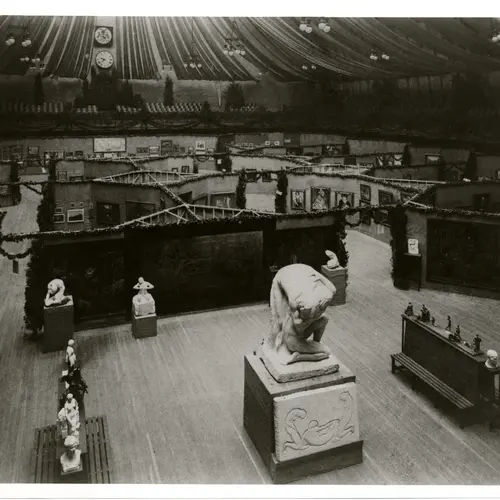

Interior view of 1913 Armory Show in New York City, 1913. Photograph, b&w. 21 x 26 cm. Walt Kuhn, Kuhn family papers, and Armory Show records, 1882-1966. Archives of American Art.

It all began in 1913 when the International Exhibition of Modern Art, or simply, the Armory Show, as the legendary exhibit came to be known, rocked the 69th Street Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue and proved a watershed in American tastes. It was the first time the phrase “avant-garde” was used to describe painting and sculpture, and it introduced the American public to the European vanguard.

Mabel Dodge, who hosted the most famous artistic and literary salon in the country at her home at 23 Fifth Avenue, was “the guiding light” of the Armory Show. She called the show “the most important public event…since the signing of the Declaration of Independence,” and predicted to her friend Gertrude Stein that the show would cause “a riot and a revolution and things will never be the same again.”

“Mrs. J.D. Rockefeller Jr.” (Abby Aldrich Rockefeller), August 1918, via The Library of Congress

You may have spent time in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller sculpture garden at the Museum of Modern Art, which is free and open to the public. The garden is named in honor of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller because she founded the Museum of Modern Art in 1929.

Rockefeller began collecting the work of the American and European avant-garde in 1925, and established the “Topside Gallery” in her home on 54th street in 1928 to display her collection. At the same time, New York’s leading museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, staunchly refused to exhibit contemporary works. To challenge those policies, Rockefeller joined together with Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan to found MoMA, which they hoped would provide New York with “the greatest museum of modern art in the world.”

Bliss, who had helped finance the Armory Show, built a collection of Modern Art that formed the basis of MoMA’s permanent collection. In fact, her collection made possible the Museum’s very first exhibit, “Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh.”

Mary Quinn Sullivan was an artist as well as a patron of the arts. She studied at Pratt, worked as an art teacher in Queens, and was sent by New York City Board of Education to observe art curricula throughout Europe.

By 1909 she became head of the art department at Dewitt Clinton High School and supervisor of the New York City elementary school drawing curriculum. By 1910 she was an instructor at Pratt, and in 1917, she began collecting Modern Art. That collection brought her to the attention of Bliss and Rockefeller, who recruited her for their museum project over lunch in 1929.

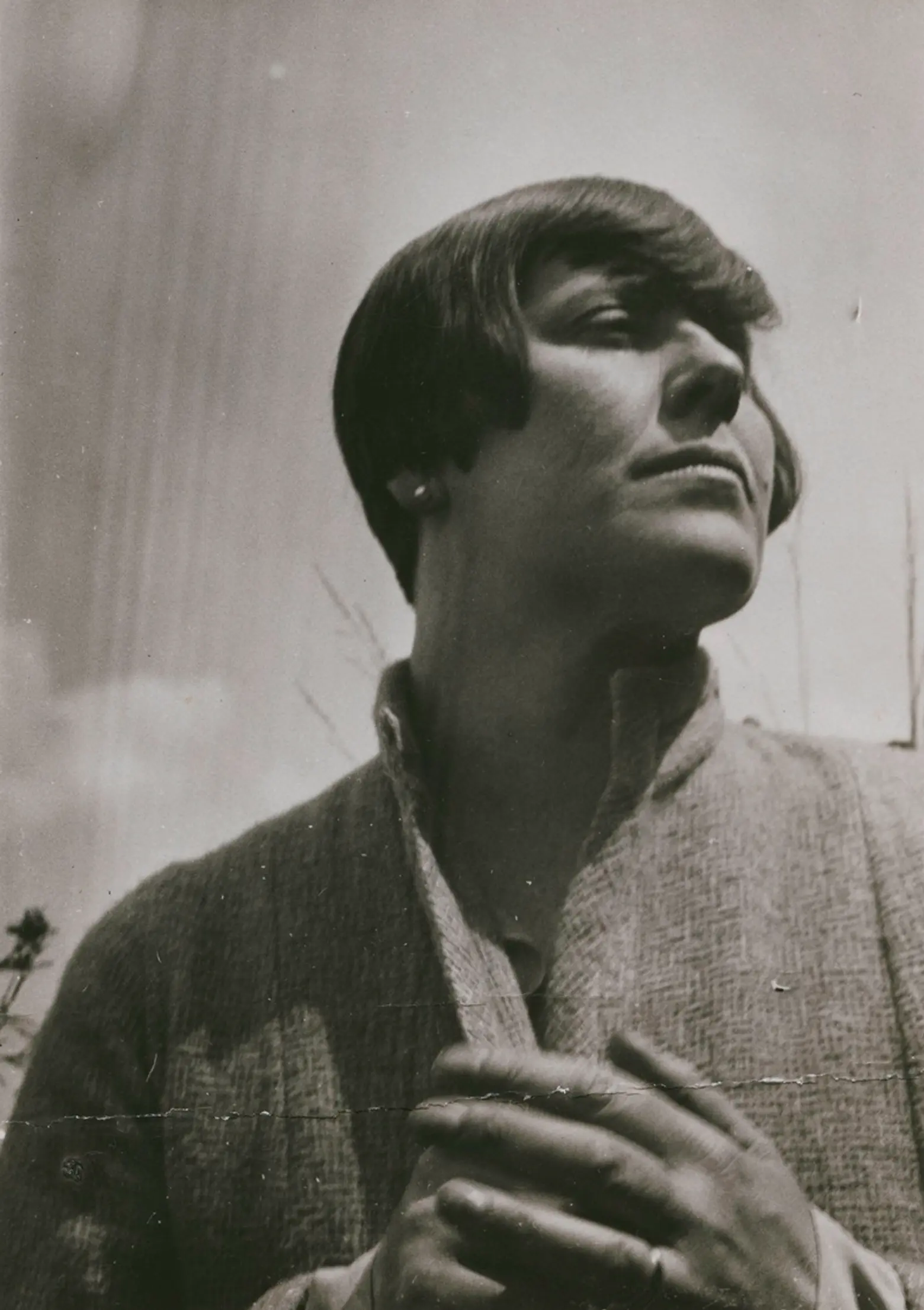

“Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, half-length portrait, standing with statue of soldiers,” 1920, via The Library of Congress

“Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, half-length portrait, standing with statue of soldiers,” 1920, via The Library of Congress

Mary Quinn Sullivan was not the only working female artist to found a museum in New York City, nor the only one to do so in direct opposition to the stuffy policies of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Another such artist/collector/founder was Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

Like other patrons of the arts, Whitney was an extraordinarily wealthy woman, but she was also a serious and talented sculptor, known for her monumental works. For example, she created the Washington Heights-Inwood War Memorial at Mitchel Square Park.

By 1907, she had established a studio in the converted carriage house at 8 West 8thStreet, in Greenwich Village, which is now home to the New York Studio School. The 8th street studio also housed an exhibition space and salon, and in 1914, Whitney broadened her presence in the Village, establishing the Whitney Studio Club at 147 West 4th Street, as space where young artists could gather. She passionately supported women artists, and was known for her support of independent America painters, even providing housing and living stipends for them.

By 1929, Whitney had amassed a collection of more than 700 works of American Modern Art. She offered that collection to the Met, along with full funds for the museum to build a wing to house the work. The Met declined on the grounds that it did not exhibit American Art, so Whitney decided to found her own museum in 1930. Accordingly, Whitney’s 8th street studio became the first home of the Whitney Museum. Continuing her support for women, Whitney appointed Juliana Force as the Museum’s very first director.

Hilla von Rebay photographed by László Moholy-Nagy, 1924 via Wikimedia Commons

The Guggenheim might be named for the collector Solomon R. Guggenheim, but the museum began its life in 1939, in a converted automobile showroom on 54th street, as “The Museum of Non-Objective Painting,” under the guidance of the German-born artist Hilla von Rebay, who served as the Museum’s first director and curator. It was she who urged Guggenheim to collect non-objective painting, she who created the Museum’s first exhibit, “Art of Tomorrow” (which included 14 of her own works), and she who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the Guggenheim’s permanent home, which she hoped would be a “temple” or “monument” to the spirit of art. She served as the Museum’s director until 1952, when the institution was officially renamed in honor of Guggenheim.

Rebay was born a Baroness in Imperial Germany. She studied art in Cologne, Paris, and Munich. While in Munich, she was exposed to Modern Art. Soon, she became part of the avant-garde scene in Berlin and Zurich, exhibiting in such places as the Galerie Dada.

In 1927, she moved to New York, and in 1928 began a portrait of Solomon R. Guggenheim. The following year, she guided Guggenheim to purchase work by Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Kandinsky.

She began exhibiting that collection at the Plaza Hotel in 1930-31. Throughout the 30s, she wrote a catalog for the collection and began organizing traveling exhibitions for the works, sending pieces to schools and civic organizations around the country.

“Mrs. Aileen Osborn Webb and Paul J. Smith with pottery by Hui Ka Kwong for the Second International Ceramics Exhibition in Ostend, Belgium, 1959,” via The American Craft Council Library and Archives Digital Collections

“Mrs. Aileen Osborn Webb and Paul J. Smith with pottery by Hui Ka Kwong for the Second International Ceramics Exhibition in Ostend, Belgium, 1959,” via The American Craft Council Library and Archives Digital Collections

Aileen Osborn Webb founded the Museum of Art and Design. She is credited with carving a respected place for crafts in the world of American Fine Art. When MAD opened in 1956, it was known as the Museum of Contemporary Crafts. The Museum’s original mission was to recognize the crafts of living, contemporary American artists. Webb, who also founded the American Craft Council, understood that craft had inherent value as a part of the nation’s heritage, and that it was a means of economic self-sufficiency for generations of artisans.

Webb’s respect for craft grew out of an exceptionally privileged upbringing, steeped in Fine Art, coupled with a serious commitment to Democratic values. Webb was born into a family of art patrons. Her father, William Church Osborne was president of the Board of Trustees at the Met from 1941 – 1948, and she married into the Vanderbilt family.

By the 1920s, she became involved in Democratic politics and served as Vice Chairman of the New York Democratic Party, where she became friendly with Eleanor Roosevelt. Her association with the Roosevelts and the influence of their New Deal programs led to her involvement with American crafts. In the 1930s, when the Depression put so many Americans out of work, Webb created Putnum County Products, a shop and marketing group focused on “selling whatever a person living in Putnum County could make or produce.”

The shop grew into a home-industry program that sold agricultural products, quilts, pottery, and other handmade, traditional wares produced in both rural and urban areas of the northeast, which offered artisans a platform to earn a living.

By 1939, the program had grown throughout the country, and Webb founded the Handicraft Cooperative League of America, uniting small, regional groups into a National Craft Movement. By 1940, the League opened America House, a cooperative shop on 54th Street, which worked to bring rural crafts to urban centers. The Museum of Contemporary Crafts was part of that work, as was the American Crafts Council. Finally, Webb took her mission global, founding the World Crafts Council in 1964.

“Marcia Tucker, Self-Portrait” via Wikimedia Commons

“Marcia Tucker, Self-Portrait” via Wikimedia Commons

Marcia Tucker, born in Brooklyn in 1940, founded the New Museum on January 1, 1977. Tucker had cut her teeth as Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Whitney, a position she held from 1967-1976.

At the New Museum, Tucker hoped to give the care and attention that work by established artists received at older institutions, to work produced by contemporary artists. Tucker was devoted to “new art and new ideas,” and she imagined a museum that would sell its collection and rebuild it every 10 years, in order to remain truly contemporary. In fact, Tucker saw the museum as a “laboratory” instead of a traditional museum.

Experimentation at the New Museum’s “laboratory” included groundbreaking programs and exhibits such as 1978’s ‘Bad’ Painting exhibit, which questioned concept of taste; the 1980 launch of the High School Art Program, one of the first museum education programs in the country to connect high-risk students with contemporary art; 1982’s “Extended Sensibilities: Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art,” the first exhibition to consider the aesthetics of artists who identify as gay and lesbian, and the 1996 publication of the New Museum’s Contemporary Art and Multicultural Education guide, which featured artists’ statements in English and Spanish, and included lesson plans for using contemporary art to explore topics including American identity, the dynamic definition of “family,” the AIDS crisis, discrimination, racism, homophobia, and artistic movements in mass media, and public art.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.