Macy’s, Lord & Taylor, and more: The history of New York City’s holiday windows

Shoppers check out a holiday window, via The Library of Congress

Santa rode in on his sleigh at the end of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and the Christmas Tree is now lit at Rockefeller Center, so you know what that means: It’s officially the holiday season in New York. It’s fitting that Macy’s heralds the beginning of our collective good cheer since R. H. Macy himself revolutionized the holiday season when he debuted the nation’s very first Christmas Windows at his store on 14th Street in 1874. Since then, all of New York’s major department stores have been turning merchandise into magic with show-stopping holiday window displays. Historically, New York’s holiday windows have deployed a combination of spectacle, science, and art, with cutting-edge technology and the talents of such luminaries as Andy Warhol, Salvador Dali, and Robert Rauschenberg. From hydraulic lifts to steam-powered windows, take a look back at the history of New York’s holiday windows, the last word in high-tech, high-design holiday cheer.

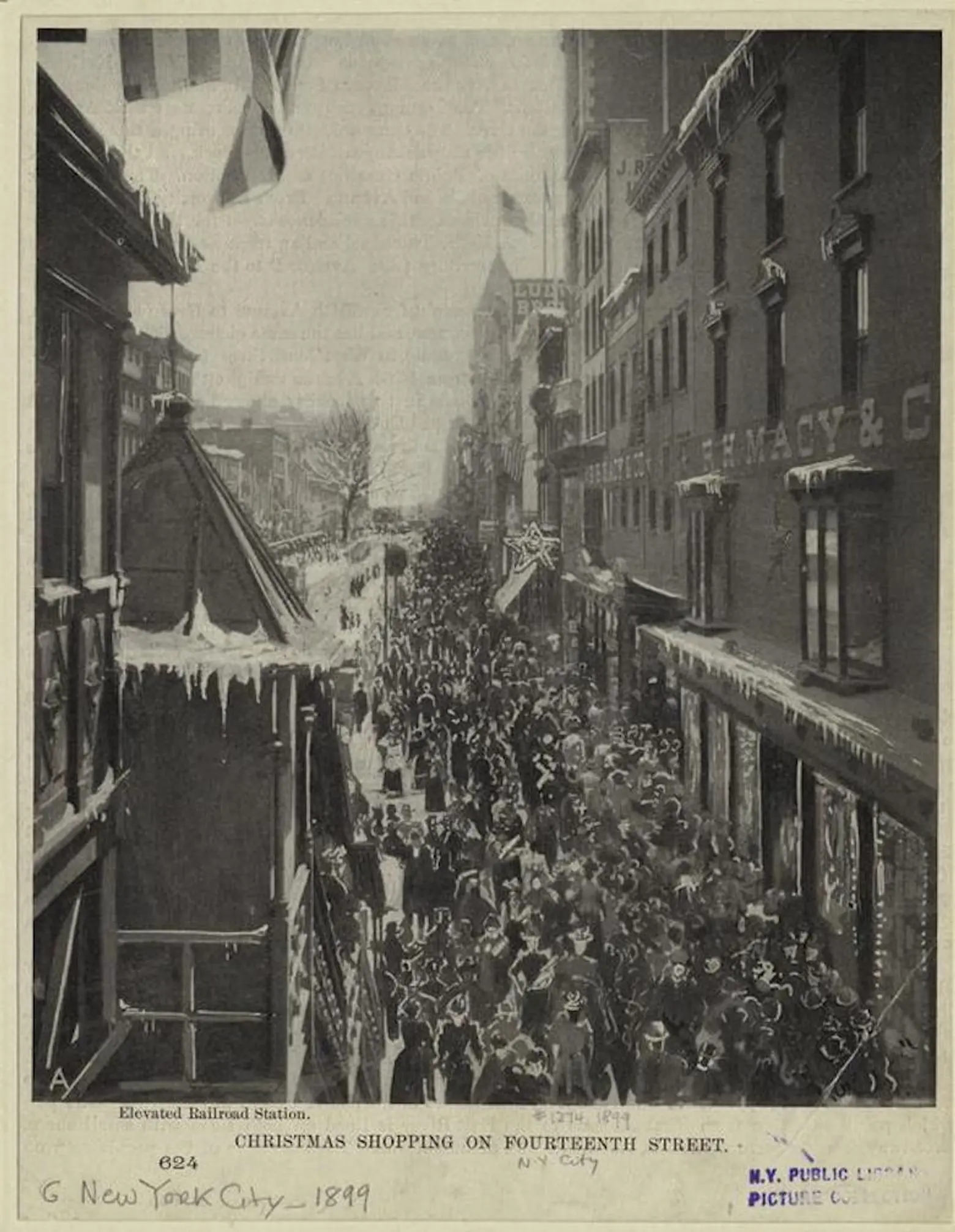

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Christmas shopping on Fourteenth Street” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1899. via NYPL

Today, it’s the holiday decorations that compel us to press our noses up against the windows at Bergdorf’s, Saks, and Macy’s, but when department stores began to proliferate in New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was the large plate-glass windows themselves that made the shopping experience magical. Because the industrial revolution had made plate-glass inexpensive and accessible, store owners could build large windows, spanning the full length of their stores, showcasing merchandise like never before.

Larger windows inspired “window shopping” and retailers looked for ways to convert window shoppers into bona fide customers. Since November and December are the busiest time in the retail calendar, with stores selling upwards of 25 percent of their wares between Thanksgiving and the New Year, the holiday season was the most logical time to invest in enticing displays.

From Macy’s, the craze for holiday windows spread along 14th Street and up through the Ladies’ Mile, before docking along 5th Avenue, where retailers continue to try to outdo one another every year.

In the late 19th century, that meant making use of state-of-the-art technology like electric light, and steam power. With those advances, Display Men (and Women) as they were known in the window trimming trade, could create animated worlds within each window, instead of static displays.

The first animated window, dubbed “Dolls’ Circus” debuted in 1881 at Ehrich Brothers on 6th Avenue and 18th Street. In 1883, Macy’s conjured a steam-powered window featuring figures on a moving track. In 1901, the store served up a “Red Star Circus,” complete with animated riders, clowns, jugglers, and acrobats.

By 1897, holiday window dressing was such a heated enterprise, L. Frank Baum, who wrote the “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” and was thereby an authority on all things magical, began publishing “The Show Window,” a magazine devoted entirely to holiday window displays, which awarded prizes to the best designs. Baum saw the artistry in each window and aimed to raise “mercantile decorating” to the status of a profession by founding the National Association of Window Trimmers.

But, by the 1920s, this brotherhood of window trimmers went unseen, for they worked beneath their displays, sending finished designs up on hydraulic lifts. Lord & Taylor was the first to use these “Elevator Windows,” where holiday scenes appeared as if by magic.

Magic was the stock in trade of James Albert Bliss, the great impresario of New York window design in the 1930s and 40s. Bliss created holiday windows for Lord & Taylor’s, Macy’s, and Wanamaker’s, and coined the term “visual merchandising.” He believed that display design was a “langue of inspired, imaginative showmanship” and “creative make-believe.”

Creative make-believe was the guiding tenant of 1930s holiday display when Lord & Taylor president Dorothy Shaver conceived windows that would provide a “free show.” At a time when Depression-strapped New Yorkers, who certainly couldn’t afford the theater, needed a little theatricality, free of charge, Lord and Taylor’s delivered. In the early ‘30s, the store’s windows featured animated scenes powered by electric motors that put on a show for passersby.

Then, in 1937, Shaver and Bliss revolutionized holiday windows. That year, at Lord & Taylor, Bliss created “Bell Windows” a holiday window display without merchandise. The Bell Windows, showing ringing bells over a snowy winter landscape, became the first purely decorative holiday windows ever produced, and they were such show-stoppers, they returned each year until 1941.

While Bliss’s incredible holiday windows were meant to draw shoppers into the store, sometimes his windows came out of the store to the shoppers. For example, in the 1948 display he created for Macy’s, children in front of the window could drop letters for Santa into a mailbox on the street connected to the display behind the window. In the display, the letters seemed to travel up a conveyor belt to an animated Santa Claus who stamped them, “received.”

But Bliss wasn’t the only showman on 5th Avenue. High fashion has always meant high art, and at some of New York’s most illustrious stores, like Tiffany’s or Bonwit Teller, Salvador Dali, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, and Robert Rauschenberg all tried their hand at window dressing. (Dali was so incensed that Bonwit Teller altered his 1939 windows showcasing a mannequin sleeping on a bed of hot coals against a water-buffalo headboard, that he smashed through the window in a rage, and fell out onto the street).

Children at the Macy’s toy window, ca. 1910 via George Grantham Bain Collection, The Library of Congress

Children at the Macy’s toy window, ca. 1910 via George Grantham Bain Collection, The Library of Congress

Clearly, Dali was ahead of his time when it came to holiday windows. But, by 1976, he would have fit right in. That year, the artist and ex-hustler Victor Hugo, who was at work on Halson’s Madison Avenue windows, had to call Andy Warhol to ask if Warhol had broken into the window and stolen a display of turkey bones he was working on for the holidays.

Today’s holiday windows err on the sweeter side but, as ever, showmanship reigns supreme. Currently, the windows at Saks feature kaleidoscope and toys that move with programmed LED lights, 60,000 lights on the building’s facade, synchronized with a medley of Elton John songs, including “Step Into Christmas” and “Your Song.”

+++

Editor’s note: The original version of this story was published on November 28, 2018, and has since been updated.

RELATED:

- The Urban Lens: Vintage photos document the origins of Black Friday shopping in NYC

- The history of the Rockettes: From St. Louis to Radio City

- The history of the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree, a NYC holiday tradition

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

By “guiding tenant” – do you mean “tenet”?