INTERVIEW: Legendary architect Beverly Willis on gender equity in the building and design industry

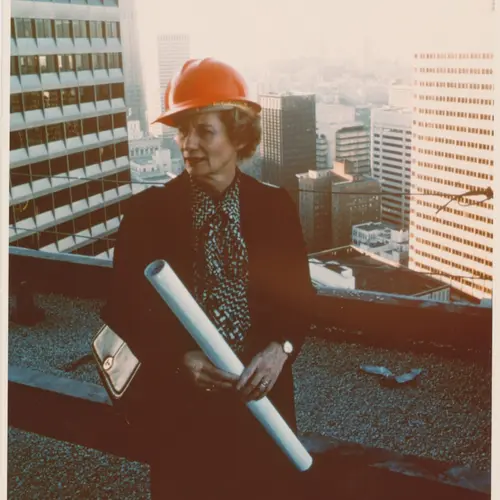

Photo of Beverly Willis courtesy of BWAF; photo of the San Francisco Ballet Building courtesy of Wikimedia

Throughout her more than 70-year-career, Beverly Willis has made an impact on nearly every aspect of the architecture industry. Willis, who began her professional career as a fresco painter, is credited with pioneering the adaptive reuse construction of historic buildings. She also introduced computerized programming into large-scale land planning and created a permanent prototype for buildings designed exclusively for ballet, with the San Francisco Ballet Building, one of her most iconic and enduring projects. As a woman in the building industry during the middle of the 20th century, and without any formal architectural training, Willis faced barriers that her male co-workers did not.

After decades of success, instead of retiring Willis, founded the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation (BWAF), aimed at shining a light on women architects who were left out of the history books. In 2017, BWAF launched a website, “Pioneering Women of American Architecture,” that profiles 50 women who made significant contributions to the field. Ahead, architect Beverly Willis talks with 6sqft about how she became a pioneer in the field, the goals of her foundation and her continued push for gender equity in architecture, and beyond, through education and research.

Willis working on her fresco for the United Chinese Society in Hawaii (1954) via Beverly Willis Archive

How did you get your start in the architecture and design field?

Well, actually I started out as an artist. My first career was in art. I was a fresco painter, and sort of expanded my art practice to include multi-media. Which led me into industrial design, which led me into architecture. And I became a licensed architect in 1966. And have basically, practiced architecture since then.

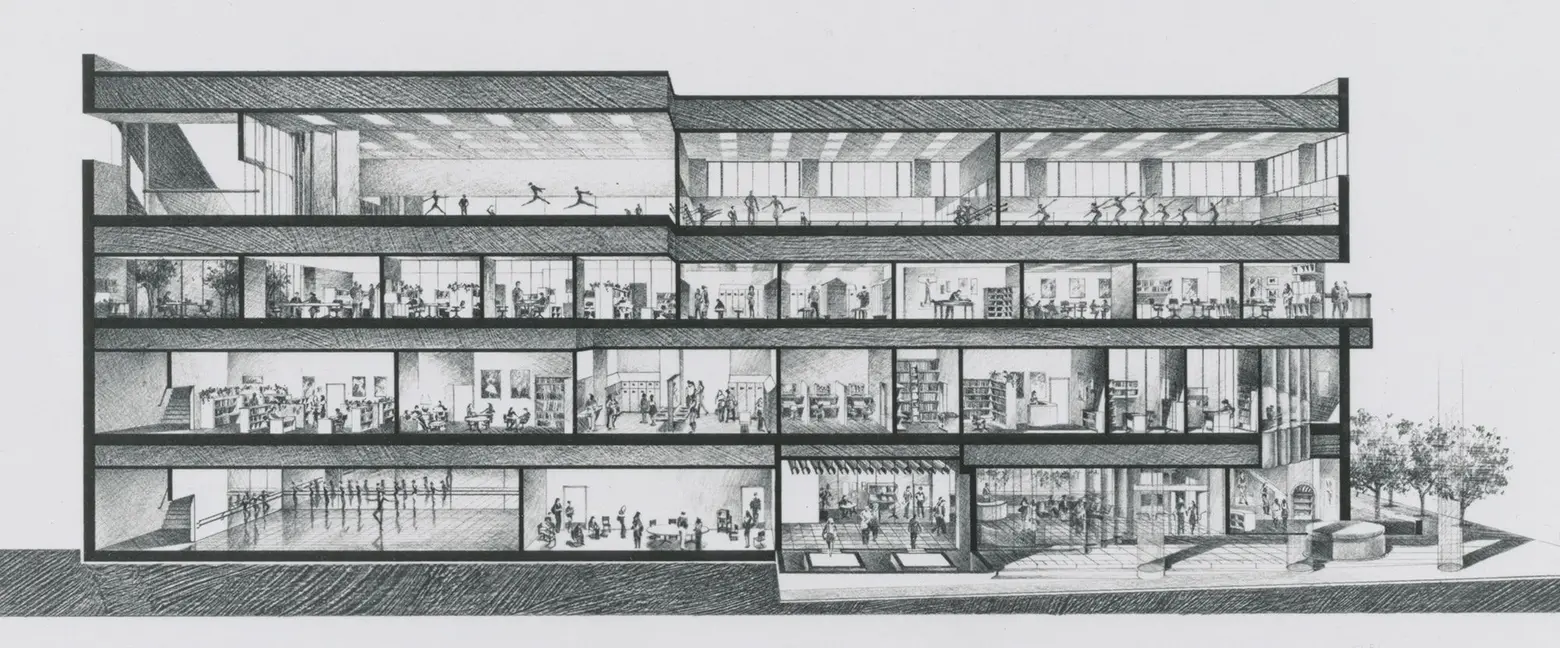

The facade of the San Francisco Ballet Building, the first to be designed exclusively for a ballet institution via Beverly Willis Archive

Preliminary section showing uses of San Francisco Ballet Building from Beverly Willis & Associates (1979) via Beverly Willis Archive

Can you tell me a little bit about the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, and how did it come to be, in 2002?

Well, I was 75 years old at that time. And it was rather a belated realization, but I think, like so many other women, I was so engrossed in my practice, that, you know, I wasn’t paying much attention to history. And then I discovered that women were not in the history books, and needless to say, was very shocked and thought really, something had to be done about it.

So, that prompted me to found the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation with that goal in mind, of seeing that deserving designers were in fact included in the history of architecture. It’s a very serious matter for women, because if you’re a young girl in high school taking architectural history or even art history – and the same thing if you’re at university – and you see no women in any of your history books, it sort of conveys to you that either women’s work is not worth being mentioned, or – I guess that’s primarily it. That no women had ever really risen to that standard.

That’s very untrue. And, in many cases, most recently being Zaha Hadid – she was literally the best architect in the world. So, the initial premise for building this architectural foundation is trying to do something on that. We’re still working on it. But, you know, it really became obvious that, for a non-profit organization, we had to raise money. And you know, it’s very difficult to raise money from dead women. So, then we enlarged our programs to promote equity for women in the building industry.

Adaptive reuse renovation at the Union Street Shops in San Francisco (1965) via Beverly Willis Archive

What do you think can be done to get more women involved and to be recognized? Is it part of our education system that doesn’t do the job?

It is very definitely part of our education system. And architectural historians have to recognize this lack and correct it. Because they’re the ones that are writing history. We have had one success with one historian – Gwendolyn Wright, very prominent historian – who in her survey of modern architecture called “USA” a few years ago, it includes women’s names in every chapter of the book. But that was a survey, so to speak, and wasn’t in a sense, you know, the typical history book.

Willis leading a project meeting for Beverly Willis & Associates (1979) via Beverly Willis Archive

Were there any barriers that you faced that you saw your male co-workers did not face?

Well, when you’re competing against another firm, you know, for work, the elbows can get quite sharp. And you know, one of the things that the men would say, in competition with me, or my firm, was “why would you hire a woman to design? Everybody knows women can’t design as well as men, and why not hire me, a man?” That sort of thing. So that was the way that competitive firms sort of turned my gender around as a liability, not an asset.

The website your foundation launched features 50 pioneering women in the field, born before 1940. Will you focus on up-and-coming architects? What’s next?

I’m currently doing a film called “Unknown New York: The City That Women Built” and this will basically be about contemporary women – some historical women, but basically contemporary women – because the flowering, so to speak, and the outpouring of women’s work in Manhattan has been pretty much in the last 20 years. It’s, you know – some of the largest projects in Manhattan. It’s been some of the biggest buildings in Manhattan. So, you know, it’s truly astounding.

Willis’ River Run Residence and its “Z” shaped pool in St. Helena, CA (1983) via Beverly Willis Archive

What does the website mean to you as a pioneering woman yourself?

It means a great deal. Because, as I said to you previously – it’s really up to the historians to guide this work into the formal history books. And this work has been done by historians across the United States – and prestigious historians – who have sort of taken on chapters of various women, and this is the work that, if you were trying to research it from scratch as an individual historian – you know, it’d be many, many, many years of you know, getting to the point that we have gotten to – actually it’s taken us a number of years ourselves to put this together.

With all of your work over the last few decades, do you think we’re progressing and getting closer to gender equity in architecture?

Well, I think it’s going to be a much longer effort. I don’t know if I like that word – but effort, it’s you know, a very slow process, unfortunately. But, I will say that, since we got started, we have instigated a women’s movement across the country, and there are now women’s organizations in most or all of the large firms.

+++

The Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation’s new website, “50 Pioneering Women of American Architecture,” required hundreds of interviews and hours of diving into archives. The collection is peer-reviewed. Explore it further here.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

RELATED: