Dorrance Brooks Square: A Harlem enclave with World War and civil rights ties

Photo courtesy of the Dorrance Brooks Property Owners and Residents Association

This post is part of a series by the Historic Districts Council, exploring the groups selected for their Six to Celebrate program, New York’s only targeted citywide list of preservation priorities.

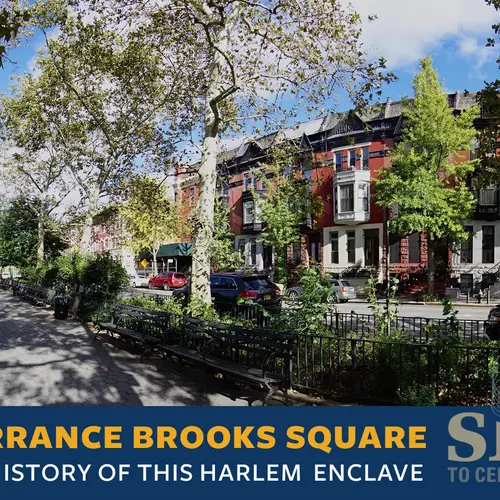

By many accounts, Dorrance Brooks Square is considered the first public square named for a black soldier. The little Harlem park, just east of the larger St. Nicholas Park, was dedicated in 1925 to honor African-American infantryman Dorrance Brooks for his bravery during WWI. Prior to that, the area was very much associated with the Harlem Renaissance, home to jazz musician Lionel Hampton and sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois, among others. Later, it became a key location for social and political gatherings and speeches during the Civil Rights era. Today, the quaint neighborhood is home to an incredibly intact collection of late 19th-century rowhouses, built at the time for upper-middle-class professionals, as well as four culturally and architecturally significant churches.

For all these reasons, the Dorrance Brooks Property Owners and Residents Association is advocating for an official landmark designation of the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District, which would run up Edgecombe Avenue between West 136th and 140th Streets. To give 6sqft more information on this history of this neighborhood, the Association has mapped out the six most significant sites.

Photo by Marissa Marvelli, courtesy of HDC

1. Dorrance Brooks Square (St. Nicholas Avenue and West 137th Street)

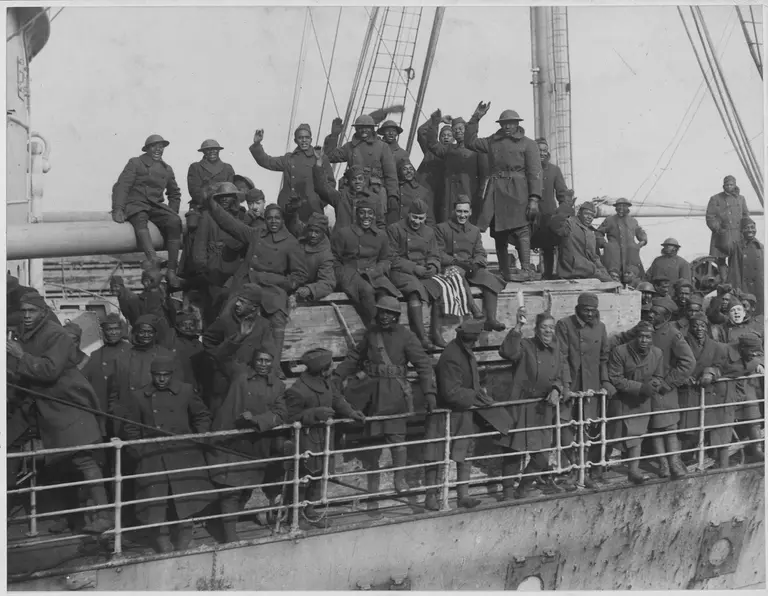

Dorrance Brooks Square was developed by the City of New York and dedicated on June 14, 1925, to commemorate the valor of black U.S. soldiers. The park is named for Dorrance Brooks (1893-1918), a Harlem native who was a Private First Class in Company 1 of the 369th Regiment. Better known as the Harlem Hellfighters, the Regiment was an all-black American unit that served under French command in World War I. Brooks was killed in France while leading his company through active combat. The Square was the first in the city, if not the state, dedicated to honor a black serviceman.

Throughout the Depression and after, Dorrance Brooks Square hosted numerous public gatherings—war commemorations, festivals, protests, and speeches. Innumerable rallies were held there to draw attention to discriminatory practices in the military, labor, and housing. In August 1934, 1,500 people gathered to celebrate the successful boycott of Blumstein’s, a white-owned department store on 125th Street that until then had refused to hire black clerks. In May 1936, thousands gathered for a mass meeting to protest the invasion of Ethiopia by Fascist Italy. In October 1937, Harlem residents gathered with signs protesting the high rents charged by white landlords. In March 1950, the NAACP leader Walter White and others rallied a large audience to demand that the U.S. Senate pass the laws proposed by the Fair Employment Practice Committee, which would ban discriminatory employment practices in the federal government. However, the largest gatherings in the history of the square likely occurred in 1948 and 1952 when President Harry S. Truman delivered major campaign speeches there.

Today, many of the rowhouses around the Square have been restored, surrounded by an allée of trees and benches. Each year on Memorial Day and Veterans’ Day, ceremonies are held here to commemorate the service of PFC Brooks and others who have served in the Armed Forces.

St. Marks United Methodist Church. Image courtesy of NY State Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation

St. Marks United Methodist Church. Image courtesy of NY State Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation

2. St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church (now St. Mark’s/Mount Calvary United Methodist Church), 59 Edgecombe Avenue

The most visually prominent church in the Dorrance Brooks Historic District is St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church (now St. Mark’s/Mount Calvary United Methodist Church). Developed in 1921-26 and designed by Sibley & Featherston, this Neo-Gothic church has played a significant role in Harlem’s social and political life over the years. The church’s architect took cues from the square-towered Shepard Hall on the Collegiate Gothic campus of City College, which looms over the neighborhood from the top of St. Nicholas Park. St. Mark’s was already among the most prominent black churches in the city. Its congregation first formed in 1871 under the leadership of Rev. William F. Butler, who was an outspoken advocate for racial equality in the years following the Civil War and a prominent black member of the Republican Party.

While the arts, civil rights, and social welfare had long been at the core of St. Mark’s mission, the church, as an institution, was also a significant physical presence in the district. In addition to hosting mass gatherings of labor unions, civil rights groups and fraternal clubs, St. Mark’s provided crucial facilities for community educational and athletic programs. In 2014, the district’s two Methodist Episcopal congregations merged into one, becoming St. Mark’s/Mount Calvary United Methodist Church.

Mount Calvary United Methodist Church, via Jim.Henderson on Wiki Commons

Mount Calvary United Methodist Church, via Jim.Henderson on Wiki Commons

3. Mount Calvary United Methodist Church (originally Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Atonement), 116 Edgecombe Avenue

One of the earliest houses of worship, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Atonement was developed between 1897 and 1898 and designed by Henry Anderson with an awe-inducing sanctuary complete with a soaring ribbed groin vault and lancet windows in the apse portraying the Evangelist in stained glass. It was constructed in the first decade of the district’s development to service the spiritual needs of the neighborhood’s German immigrant community.

In 1924, as most white residents were fleeing Harlem, the church was purchased by former members of the long-established First A.M.E. Bethel Church located at 60 West 132nd Street. The acquisition brought the new congregation both prestige and financial strain, which was not uncommon among black Harlem’s churches at the time. But by the 1940s, it boasted one of the largest Methodist congregations in Harlem. In 1946, Shirley Chisholm was hired to be a teacher in its nursery school, and she taught there for seven years. In 1968, she became the first black woman to be elected to the U.S. Congress and four years later, the first black candidate for a major party’s nomination for President of the United States.

46 Edgecombe Avenue, photo by Marissa Marvelli, courtesy of HDC

4. Murid Islamic Community in America (Formerly the Edgecombe Sanitarium), 46 Edgecombe Avenue

In 1925, a group of 17 black physicians bought the 1886 Queen Anne rowhouse at the southeast corner of Edgecombe Avenue and 137th Street to operate as a private hospital. The new institution, called Edgecombe Sanatorium, was born out of a merger with the nearby Booker T. Washington Sanatorium, which for the previous five years had been treating tuberculosis patients. At the time, the neighborhood was served by Harlem Hospital on Lenox Avenue at 136th Street, but the institution was slow to hire black nurses and physicians, and it was accused of neglecting black patients or providing poor treatment and then overcharging them for it.

Therefore, Edgecombe was organized to allow black doctors to admit patients. One such patient was the civil rights lawyer Charles Hamilton Houston, who spent eight days there in 1928 being treated for tuberculosis, an illness that stemmed from his service in France during WWI. One of the founding physicians was Dr. Wiley Wilson, who from 1919 to 1925 was married to A’Lelia Walker.

The hospital was internally connected to the house next door at 44 Edgecombe Avenue, which had a physician’s residence in the ground floor with offices and patient rooms above, as well as an operating room on the top floor. One of the first physicians to take up residence there was Dr. May Edward Chinn (1896-1980). She was also the first black woman to earn a medical degree from Bellevue Medical College, the first black woman to intern and serve on the ambulance crew of Harlem Hospital, and for a long time, she was the only black female doctor working in Harlem. She gained prominence in the 1940s for her cancer treatment work at the Strang Clinic. In 1988, the building was bought by the Murid Islamic Community in America as its American headquarters.

90 Edgecombe Avenue, Image capture: October 2017, © 2019 Google

5. 80, 90, 108 Edgecombe Avenue

In the 1920s, during the Harlem Renaissance, black Harlem became globally recognized as the center of extraordinary artistic, social, and intellectual output. A number of prominent figures associated with this flourishing resided in the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District, likely for its close proximity to City College and the elite residential blocks known as Strivers’ Row. Located east of Eighth Avenue on 138th and 139th Streets, these four rows of luxurious houses, originally called the King Model Houses, were designed by three acclaimed architects for a single developer and built in 1891. Beginning in 1919, they were home to prominent black doctors, writers, civil rights leaders, and entertainers, and their elite address became one to “strive for.”

Those who lived in the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District include the sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois, who resided with his wife and daughter in a 1890s row house at 108 Edgecombe Avenue from 1921 to 1923. Walter F. White, the civil rights activist who led the NAACP for a quarter-century, lived at 90 Edgecombe Avenue with his young family in the late 1920s. According to historian David Lewis, Mr. White turned his apartment “into a stock exchange for cultural commodities, where interracial contacts and contracts were sealed over bootleg spirits and the verse or song of some Afro-American who was then the rage of New York.” He and his wife Gladys hosted prominent figures of the period, black and white—Jules Bledsoe, Paul Robeson, James Weldon Johnson, Carl Van Vechten, Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy Parker, the Knopfs, among others. Jules Bledsoe, a singer who starred as Joe in the premiere of Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein’s Show Boat, briefly resided in the building before fame catapulted him to grander accommodations.

Even after the Renaissance, 80 Edgecombe Avenue continued to attract notable residents. By 1940, Dr. Elizabeth “Bessie” Delany and her sister, Sadie, resided there with their mother. Bessie was the second African-American woman to be a licensed dentist in New York State and was known to take patients in the neighborhood who otherwise could not afford treatment. Meanwhile, Sadie was the first African-American to teach home economics at the high school level in the New York City school system. Both sisters socialized with the likes of D.E.B DuBois, Paul Robeson, and Langston Hughes.

26-28 Edgecombe Avenue, Image capture: October 2017, © 2019 Google

26-28 Edgecombe Avenue, Image capture: October 2017, © 2019 Google

6. Church of St. Luke the Beloved Physician (now the New Hope Church of Seventh-Day Adventists), 26-28 Edgecombe Avenue

With the exodus of white residents from Harlem in the 1910s and 1920s, still-new ecclesiastical buildings were sold to black congregations. Between 1922 and 1924, four African-American churches acquired property in the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District. In 1922, the white vestry of St. Luke’s Protestant Episcopal Church, located at Convent Avenue and 141st Street, acquired a row house at 28 Edgecombe Avenue to house its new Mission for Negroes. Both the original mission at 28 Edgecombe Avenue and the adjoining brownstone at 26 Edgecombe Avenue have been acquired and combined by the New Hope Church of Seventh-Day Adventists.

Prior to its relocation to Harlem in the late 1890s, St. Luke’s was located in the West Village and had been affiliated with Trinity Church, one of the oldest and wealthiest churches in New York. Early members of the St. Luke’s Mission were West Indian families, many of whom were practicing Catholics who converted to the Episcopalian faith after moving to Harlem. Some of the founding members included the families of Dean Dixon, the renowned Classical music conductor, and Kenneth Clark, the famed Harlem sociologist and spouse of Mamie Phipps. Clark served as an altar boy there for many years. In 1952, it was rechristened the Church of St. Luke the Beloved Physician in recognition of becoming a full parish rather than a mission church. By 1999, the congregation had ceased worshipping in the building; ownership was transferred to the New Hope Church of Seventh-Day Adventists.

Between 1940 and 1960, the total black population of New York more than doubled. This growth coincided with a widespread decline in local manufacturing, particularly in the defense industry, which employed a significant number of Harlem residents. Many of the jobs that remained paid low wages, and most had no union protection. These factors, coupled with deteriorating housing conditions, contributed to social upheaval in Harlem and other black neighborhoods. Civil rights organizations continued to coordinate boycotts and rent strikes to focus greater attention on the labor and housing injustices endured by blacks. Others, like the Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU)—which was formed by the acclaimed social psychologists and civil rights activists, Drs. Mamie Phipps Clark and Kenneth Clark—focused on remedial education and job training for young people and teaching the public how to work with government agencies to secure services and funds. Within the district, We Care, a program with a related focus and supported by Dr. Mamie Clark and her Northside Center for Child Development, was headquartered in St. Luke’s Episcopal Mission at 28 Edgecombe Avenue. In 2011, the New Hope Church of Seventh-Day Adventists combined 26 Edgecombe Avenue and 28 Edgecombe Avenue into one property.

RELATED:

- 10 historic sites to discover in Mott Haven, the Bronx’s first historic district

- Six things you didn’t know about Arthur Avenue and Bronx Little Italy

- Six things you didn’t know about the Lower West Side

+++

This post comes from the Historic Districts Council. Founded in 1970 as a coalition of community groups from the city’s designated historic districts, HDC has grown to become one of the foremost citywide voices for historic preservation. Serving a network of over 500 neighborhood-based community groups in all five boroughs, HDC strives to protect, preserve and enhance New York City’s historic buildings and neighborhoods through ongoing advocacy, community development, and education programs.

Now in its ninth year, Six to Celebrate is New York’s only citywide list of preservation priorities. The purpose of the program is to provide strategic resources to neighborhood groups at a critical moment to reach their preservation goals. The six selected groups receive HDC’s hands-on help on all aspects of their efforts over the course of the year and continued support in the years to come. Learn more about this year’s groups, the Six to Celebrate app, and related events here >>